Azure-shouldered tanager

| Azure-shouldered tanager | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Genus: | Thraupis |

| Species: | T. cyanoptera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Thraupis cyanoptera (Vieillot, 1817)

| |

| |

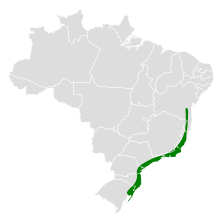

| The azure-shouldered tanager's range in Brazil | |

| Synonyms | |

The azure-shouldered tanager (Thraupis cyanoptera) is a species of bird in the tanager family, Thraupidae. Described by the French zoologist Louis Pierre Vieillot in 1817, it is only found in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil, from southeastern Bahia, eastern Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo south to northern Rio Grande do Sul. It inhabits humid montane forests, open woodlands, secondary growth, and forest edges and can be found at elevations of up to 1,600 m (5,200 ft), but usually stays below 1,200 m (3,900 ft).

The species feeds on fruit, flowers, and leaves. Its habit of eating leaves is an unusual aspect of its diet. Foraging takes place in mixed-species or single species flocks of as many as 15–20 birds. Like other tanagers in southeastern Brazil, the azure-shouldered tanager's breeding season begins after the end of the dry season. Nests are generally built deep inside tangles of epiphytic bromeliads in trees. Eggs are laid in clutches of two and may be either pale blue with some very dark purple spots or white with evenly spread-out small brown splotches. As of 2024[update], it is classified as being least concern on the IUCN Red List, an upgrade from its previous assessment of near threatened.

Taxonomy

[edit]The azure-shouldered tanager was originally described in 1817 as Saltator cyanopterus by the French zoologist Louis Pierre Vieillot on the basis of a specimen from Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro.[2][3] The generic name Thraupis is derived from the Ancient Greek word thraupis, a name for a small unidentified bird mentioned in the writings of Aristotle; in modern ornithology, it is used to denote tanagers. The specific epithet is from the Greek kuanopteros, meaning 'dark-winged' or 'blue-winged'.[4] "Azure-shouldered tanager" is the official common name designated by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOU).[5] In Brazilian Portuguese, the tanager is called sanhaço-de-encontro-azul.[6]

The IOU and The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World classify the azure-shouldered tanager in the genus Thraupis, a group of seven Neotropical species in the tanager family, Thraupidae.[5] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and BirdLife International instead place the species in the genus Tangara.[1] A 2022 phylogenetic study of the genus found the azure-shouldered tanager to be the second-most basal species within Thraupis, next to only the glaucous tanager.[7]

Description

[edit]The azure-shouldered tanager is a large, thick-billed tanager with an average length of 18 cm (7.1 in) and a mass of 41–46 g (1.4–1.6 oz). Both sexes look alike and have similar dimensions. Adults are overall bluish in color, with gray-blue upperparts and heads, darker lores, and more bluish crowns. The throat and underparts are paler than the upper body, while the rump, uppertail coverts, and tail are bright blue. The flanks have a greenish wash. The upperwing-coverts are a rich, glossy violet-blue and the greater coverts are dark with wide turquoise-blue edges. The primary coverts and flight feathers are also dusky broad turquoise fringes. The upper mandible of the bill is blackish, while the lower mandible is blue-gray. The iris is dark brown and the legs are dark horn-gray. Juveniles are duller than adults.[6]

Vocalizations

[edit]The azure-shouldered tanager's song is very different from that of other Thraupis tanagers; it has an initial assortment of soft notes, followed by clear, musical jittle-jittle-jittle, jeeeyr-jurr notes. These notes are usually repeated twice or thrice and can also be transcribed as look heeere, right heeere, drink-drink-jrrr. The song is initially complex and later becomes slower and more melodic. The species's calls include a thin sweee and several other squeaky notes.[6]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The azure-shouldered tanager is only found in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil,[8] from southeastern Bahia, eastern Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo south to northern Rio Grande do Sul. It has been reported as far west as Paraguay, but these records are thought to represent misidentified sayaca tanagers. The azure-shouldered tanager prefers forested habitats more than other Thraupis tanagers and inhabits humid montane forests, open woodlands, secondary growth, and forest edges.[6] On Santa Catarina Island, it has also been recorded from orchards.[9] It is mainly found on the Atlantic slopes of Serra do Mar. The species can be found at elevations of up to 1,600 m (5,200 ft), although it usually stays below 1,200 m (3,900 ft). It is likely non-migratory, but may migrate in the far south of its distribution.[6]

Behavior and ecology

[edit]

Diet

[edit]Azure-shouldered tanagers are frugivorous and feed on fruit, flowers, and leaves.[6][10] Species consumed include Psychotria constricta and P. velloziana,[10] the fruit of melastomes, Livistona palms,[6] and Eugenia umbelliflora,[11] flowers and leaves of Acnistus arborescens and Solanum species, and Sechium leaves. The species' habit of eating leaves is an unusual aspect of its diet.[10] Like other tanagers, azure-shouldered tanagers will chew fruit and leave parts of the fruit below the tree; although they have small gapes, they will crush larger fruit externally, allowing them to eat fruit of a variety of sizes. A study of network organization in Brazilian Atlantic Forest found the azure-shouldered tanager to have the third-largest contribution to the network topology, a fact that may be attributable to its highly frugivorous diet.[12] A study of seed dispersal in E. umbelliflora found that although azure-shouldered tanagers are likely to move seeds to places that are favorable for germination, they have a low probability of seed removal.[11]

Foraging takes place in mixed-species or single species flocks of as many as 15–20 birds. The azure-shouldered tanager's foraging behavior is similar to that of the sayaca tanager; foraging occurs in tall trees and, in Espírito Santo, in moss on large branches. The species is aggressive to sayaca tanagers.[6]

Breeding

[edit]The azure-shouldered tanager's breeding season is similar to those of other tanagers in southeastern Brazil, all of which begin after the end of the dry season.[8] Breeding has been observed in October in Espírito Santo and in September in Rio de Janeiro.[13] In Carlos Botelho State Park, São Paulo, nests in the process of being built and those with eggs have been found in September, while those containing nestlings have been found in October and November.[8] Both sexes bring grassy material and help construct the nest. Nests are generally built in tangles of epiphytic bromeliads in trees 10 to 12 m (33 to 39 ft) tall.[8][13] They are 4.13–6 m (13.5–19.7 ft) above the ground and are located deep inside the tangles, where nests are sheltered from light and rain. Azure-shouldered tanagers show some tolerance towards habitat disturbance near their nests and will sometimes build nests even in busy coastal cities.[8]

Nests are shallow bottom-supported cups and are made mainly of long strips from dry bromeliad or other leaves. The rim of the nest is lined with thin vines and the nest chamber is lined with fine plant fibers, grass leaves, and occasionally black fungal hyphae. The exact material used to line the nests can vary slightly between individuals. Nest chambers in two measured nests had an outer diameter of 13.8–15.4 cm (5.4–6.1 in), an inner diameter of 6.7–7.2 cm (2.6–2.8 in), a depth of 2.9–4.0 cm (1.1–1.6 in), and a height of 5.3–7.6 cm (2.1–3.0 in).[8]

Eggs are laid in clutches of two. The first recorded descriptions of eggs mention them as being pale blue with some very dark purple spots; however, modern descriptions have found eggs to be roughly elliptical in shape, with a white background marked with evenly spread-out small brown splotches. This discrepancy may be due to natural variation in egg background color, which is known in other Thraupis tanagers such as the sayaca tanager. Eggs have dimensions of 28.0–29.9 mm (1.10–1.18 in) by 18.2–18.6 mm (0.72–0.73 in) and a mass of 4.5 g (0.16 oz). Nestlings have pink skin, gray down, yellow-brown bills, and swollen white flanges.[8]

Parasites

[edit]Azure-shouldered tanagers are parasitized by the feather mite Amerodectes thraupicola and the cestode worm Anonchotaenia brasiliensis.[14][15]

Conservation

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: To align with updated IUCN data. (November 2024) |

The azure-shouldered tanager is classified as being least concern by the IUCN on the IUCN Red List due to its small population and ongoing habitat loss.[1] It has a small range, being found in the Atlantic Forest Lowlands Endemic Bird Area, and is uncommon to locally common within this range. It is mainly a species of humid forest and is less adept at utilizing secondary forest and forest edges than other species in its genus, which has contributed to a large decline in its range.[6] Historically, the lowland forests this species inhabits were threatened by deforestation caused by agriculture, mining, and plantations. Current threats include urbanization, industrialization, agriculture, and the construction of roads.[1] Azure-shouldered tanagers have been recorded as being traded illegally in Brazilian street markets in Rio de Janeiro.[16] The species' population is likely declining at a slow to moderate rate.[1] The azure-shouldered tanager occurs in several protected areas, including several national parks, state parks, and the Sooretama Biological Reserve. It may have a limited range outside these protected areas.[6] Recommended conservation measures for the species include documenting trends in its populations, documenting habitat loss, determining its tolerance for habitat degradation, and protecting suitable habitat.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2024). "Tangara cyanoptera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024: e.T22722537A246114518. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Vieillot, Louis Pierre (1816). Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Vol. 14. Paris: Chez Deterville. p. 104. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.20211.

- ^ Naumburg, E. M. B. (1924). "Thraupis sayaca and its allies". The Auk. 41 (1): 112. doi:10.2307/4074092. JSTOR 4074092.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 127, 385. ISBN 978-1-4081-3326-2.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (December 2023). "Tanagers and allies". IOC World Bird List Version 14.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hilty, Steven (2020-03-04). Billerman, Shawn M.; Keeney, Brooke K.; Rodewald, Paul G.; Schulenberg, Thomas S. (eds.). "Azure-shouldered Tanager (Thraupis cyanoptera)". Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.azstan1.01. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ Cueva, Diego; Bravo, Gustavo A.; Silveira, Luís Fábio (2022-10-05). Chiang, Tzen-Yuh (ed.). "Systematics of Thraupis (Aves, Passeriformes) reveals an extensive hybrid zone between T. episcopus (Blue-gray Tanager) and T. sayaca (Sayaca Tanager)". PLOS ONE. 17 (10): e0270892. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1770892C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0270892. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9534438. PMID 36197923.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zima, Paulo Victor Queijo; Perrella, Daniel Fernandes; Francisco, Mercival Roberto (2019). "First nest description of the Azure-shouldered Tanager (Thraupis cyanoptera, Thraupidae)". Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 27 (2): 122–125. doi:10.1007/BF03544456. ISSN 2178-7875.

- ^ Naka, Luciano N.; Rodrigues, Marcos; Roos, Andrei L.; Azevedo, Marcos A. G. (2001). "Bird conservation on Santa Catarina Island, Southern Brazil". Bird Conservation International. 12 (2): 129. doi:10.1017/S0959270902002083. ISSN 0959-2709.

- ^ a b c Pacheco, Fernando; Parrini, Ricardo; Kirwan, Guy M.; Alves Serpa, Guilherme (2014). "Birds of Vale das Taquaras region, Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil: checklist with historical and trophic approach". Cotinga. 36: 87–88.

- ^ a b Côrtes, Marina Corrêa; Cazetta, Eliana; Staggemeier, Vanessa Graziele; Galetti, Mauro (2009). "Linking frugivore activity to early recruitment of a bird dispersed tree, Eugenia umbelliflora (Myrtaceae) in the Atlantic rainforest". Austral Ecology. 34 (3): 256. Bibcode:2009AusEc..34..249C. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.01926.x. ISSN 1442-9985.

- ^ Vidal, Mariana M.; Hasui, Erica; Pizo, Marco A.; Tamashiro, Jorge Y.; Silva, Wesley R.; Guimarães, Paulo R. (2014). "Frugivores at higher risk of extinction are the key elements of a mutualistic network". Ecology. 95 (12): 3444–3445. Bibcode:2014Ecol...95.3440V. doi:10.1890/13-1584.1. ISSN 0012-9658.

- ^ a b Kirwan, Guy M. (2009). "Notes on the breeding ecology and seasonality of some Brazilian birds". Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 17 (2): 133.

- ^ Hernandes, Fabio A. (2021-12-07). "New records of feather mites (Sarcoptiformes: Proctophyllodidae) on tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae) from Brazil". Entomological Communications. 3: ec03039. doi:10.37486/2675-1305.ec03039. ISSN 2675-1305.

- ^ Phillips, Anna J.; Georgiev, Boyko B.; Waeschenbach, Andrea; Mariaux, Jean (2014-10-30). "Two new and two redescribed species of Anonchotaenia (Cestoda: Paruterinidae) from South American birds". Folia Parasitologica. 61 (5): 454. doi:10.14411/fp.2014.058.

- ^ Matias, C. A. R.; Oliveira, V. M.; Rodrigues, D. P.; Siciliano, S. (2012). "Summary of the bird species seized in the illegal trade in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil" (PDF). TRAFFIC Bulletin. 24 (2): 84.