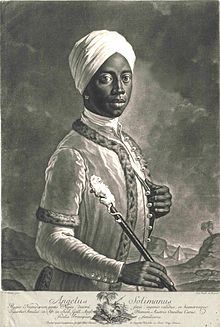

Angelo Soliman

Angelo Soliman | |

|---|---|

Angelo Soliman in 1750 | |

| Grand Master of True Concord (Given name of Massinissa) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mmadi Make c. 1721 present day Nigeria or Cameroon |

| Died | 21 November 1796 (aged 74–75) Vienna |

| Spouse | Magdalena Christiani (née de Kellermann) |

| Occupation | Freemason |

| Nickname | Massinissa |

Angelo Soliman, born Mmadi Make, (c. 1721 – 1796) was an African-born Austrian Freemason and courtier. He achieved prominence in Viennese society and Freemasonry.

Life

[edit]His original name, Mmadi Make,[1] is linked to a princely class[citation needed] of the Bornu Empire (centred in Borno State, modern-day Nigeria). He was taken captive as a child and arrived in Marseilles as a slave. He was sold into the household of a Messinan marchioness, who oversaw his education. Out of affection for another servant in the household, Angelina, he adopted the name 'Angelo', and he chose to recognize September 11, his baptismal day, as his birthday. After repeated requests, he was given as a gift in 1734 to Prince Georg Christian, Prince von Lobkowitz, the imperial governor of Sicily. He became the Prince's valet and traveling companion, accompanying him on military campaigns throughout Europe and reportedly saving his life on one occasion, a pivotal event responsible for his social ascension. After the death of Prince Lobkowitz, Soliman was taken into the Vienna household of Joseph Wenzel I, Prince of Liechtenstein, eventually rising to chief servant. Later, he became royal tutor of the heir to the Prince, Aloys I.[2][3] On February 6, 1768, he married the noblewoman Magdalena Christiani, a young widow and sister of the French general François Christophe de Kellermann, Duke of Valmy, a marshal of Napoleon Bonaparte.[4]

A cultured man, Soliman was highly respected in the intellectual circles of Vienna and counted as a valued friend by Austrian Emperor Joseph II and Count Franz Moritz von Lacy as well as Prince Gian Gastone de' Medici. Soliman attended the wedding of Emperor Joseph II and Princess Isabella of Parma as a guest of the Emperor.[5] Aside from his native Kanuri, he spoke six languages fluently: Latin, English, French, German, Italian and Czech.[6]

In 1783, he joined the Masonic lodge "True Concord" (Zur Wahren Eintracht), whose membership included many of Vienna's influential artists and scholars of the time, among them the musicians Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn as well the Hungarian poet Ferenc Kazinczy. Lodge records indicate that Soliman and Mozart met on several occasions. Eventually becoming the Grand Master of that lodge, Soliman helped change its ritual to include scholarly elements. This new Masonic direction rapidly influenced Freemasonic practice throughout Europe.[7] Soliman is still celebrated in Masonic rites as "Father of Pure Masonic Thought", with his name usually transliterated as "Angelus Solimanus".[8]

During his lifetime Soliman was regarded as a model to the "potential for assimilation" of Africans in Europe, but after his death his image was subject to defamation and vulgarization through scientific racism, and his body was physically rendered into a specimen, as if an animal or for experimentation. Wigger and Klein distinguish four aspects of Soliman – the "royal Moor", the "noble Moor", the "physiognomic Moor" and the "mummified Moor".[9] The first two designations refer to the years prior to his death. The term "royal Moor" designates Soliman in the context of enslaved Moors at European courts, where their skin color marked their inferiority and they figured as status symbols betokening the power and wealth of their owners. Bereft of his ancestry and original culture, Soliman was degraded to an "exotic-oriental sign of his lord's standing" who was not allowed to live a self-determined existence. The designation "noble Moor" describes Soliman as a former court Moor whose ascent up the social ladder due to his marriage with an aristocratic woman made his emancipation possible. During this time Soliman became a member of the Freemasons and as lodge Grand Master was certainly considered equal to his fellow Masons even though he continued to face a thicket of race and class prejudices.

At the end of his life, after the death of his European wife, the old man led an austere life that resembled very closely that of a practicing Muslim: “He no longer invited friends to dine with him. He never drank anything except water.” Angelo Solimann, his youth notwithstanding, had rebelled against conversion but then likely found it easier to accept with seeming sincerity, out of commodity or gratitude. Nevertheless, he seems to have gone back to his original faith in his old age.[10]

Mummification after death

[edit]

Beneath the surface appearance of integration lurked Soliman's remarkable destiny. Though he moved smoothly in high society, the exotic quality ascribed to him was never lost and over the course of his lifetime was transformed into a racial characteristic. The qualities used to categorize Soliman as a "physiognomic Moor" were set forth by pioneering Viennese ethnologists during his lifetime, framed by theories and assumptions concerning the "African race". He could not escape the taxonomic view that focused on typical racial characteristics, i.e., skin color, hair texture, lip size and nose shape.

Instead of receiving a Christian burial, Soliman was – at the request of the director of the Imperial Natural History Collection – skinned, stuffed and made into an exhibit within their cabinet of curiosities.[11][12] Decked out in ostrich feathers and glass beads, this mummy was on display until 1806 alongside stuffed animals, transformed from a reputable member of intellectual Viennese society into an exotic specimen. By stripping Soliman of the insignia of his lifetime achievements, ethnologists instrumentalized him as what they imagined to be an exemplary African "savage". Soliman's daughter Josefine sought to have his remains returned to the family, but her petitions were in vain. During the October revolution of 1848, the mummy burned. A plaster cast of Soliman's head made shortly after his death of a stroke in 1796 is still on display in the Rollett Museum in Baden. His grandson was the Austrian writer Eduard von Feuchtersleben.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]- In 2010, Blackamoor Angel, an opera with book and libretto by Carl Hancock Rux and music by Deidre Murray performed, in part, at Bard Spiegeltent and the Joseph Papp Public Theater under the direction of Karin Coonrod[14]

- In 2018, Angelo, a movie biopic based on his life directed by Markus Schleinzer, was released.[15]

- Flights by the Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk includes three (presumably) fictional letters by Soliman's daughter Josefine to the Austrian Emperor Francis II.[16]

- In 2014, the Hungarian writer Gergely Péterfy published the historical novel Kitömött barbár, translated into German in 2016 as Der ausgestopfte Barbar ("The stuffed barbarian"), based on the life of Ferenc Kazinczy, Soliman's friend, and his and his widow's quest to see the mummified body of Soliman in person.

Sources

[edit]- ^ "Geschichte der Afrikanistik in Österreich". Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ^ Geschichte der Afrikanistik in Österreich: Angelo Soliman (English Translation) Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Angelo Soliman und seine Freunde im Adel und in der geistigen Elite (in German)

- ^ Wilhelm. A. Bauer, A. Soliman, Hochfürstlische Der Mohr, W. Sauer (Hg), 1922

- ^ Morrison, Heather (2011). "Dressing Angelo Soliman". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 44 (3): 361–382. doi:10.1353/ecs.2011.0001. JSTOR 41057347. S2CID 154935902. Project MUSE 423078 ProQuest 864037095.

- ^ "An exceptional life, an ignominious death". The Economist.

- ^ Steele, Tom (2007). Knowledge Is Power! The Rise and Fall of European Popular Educational Movements, 1848–1939. Peter Lang. p. 315. ISBN 978-3-03910-563-2.

- ^ Moore, Keith (2008). Freemasonry, Greek Philosophy, the Prince Hall Fraternity and the Egyptian (African) World Connection. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781438909059.

- ^ Wigger, Iris; Klein, Katrin (2009). "Bruder Mohr". Angelo Soliman und der Rassismus der Aufklärung. In: Entfremdete Körper. Rassismus als Leichenschändung. Ed. Wulf D. Hund. Bielefeld: Transcript. pp. 81–115. ISBN 978-3-8376-1151-9. [1]

- ^ Diouf, Sylviane A (2013). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (15 ed.). New York: NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4798-4711-2.

- ^ "Monika Firla". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ^ Seipel, W. (1996). Mummies and Ethics in the Museum. In: Human Mummies. Ed. Konrad Spindler et al. Vienna: Springer. pp. 3–7. ISBN 3-211-82659-9. These circumstances are omitted in the early biographical notes by the Abbé Henri Grégoire – for an English translation see: "Biographical Account of the Negro Angelo Soliman". The Monthly Repository of Theology and General Literature. 11 (127): 373–376. 1816.

- ^ Wilhelm A. Bauer, Angelo Soliman, der hochfürstliche Mohr. Ein exotisches Kapital Alt-Wien. Vienna: Gerlach & Wiedling, 1922

- ^ "Diedre Murray: Stringology, by David Grundy".

- ^ Guy Lodge, "Film Review: ‘Angelo’". Variety, September 29, 2018.

- ^ Tokarczuk, Olga (2017) trans. Jennifer Croft, Flights, Text Publishing, Melbourne.