Alexander Falconbridge

Alexander Falconbridge (c. 1760–1792) was a British surgeon who took part in four voyages in slave ships between 1782 and 1787. In time he became an abolitionist and in 1788 published An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa. In 1791 he was sent by the Anti-Slavery Society to Granville Town, Sierra Leone, a community of freed slaves, where he died a year later in 1792.

Early life

[edit]Falconbridge was born around 1760 in England or Scotland, possibly Prestonpans or Bristol.[1]

The slave trade

[edit]The British surgeon Alexander Falconbridge served as a ship's surgeon on four slave trade voyages between 1782 and 1787 (on the ships Tartar (1780–1781), Emilia (1783-84), Alexander (1785-86) and, again, Emilia (1786-87)[2] before rejecting the slave trade and becoming an abolitionist. (In 1782, French naval forces captured Tartar on her second voyage to transport enslaved people, but before she had taken on any captives.)

Falconbridge gained his experience on slave ships before he met the anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Clarkson[3] following which he became a member of the Anti-Slavery Society. Clarkson was the author of a pamphlet entitled A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition, published in 1787. Clarkson had a high regard for Falconbridge who on more than one occasion acted as his personal armed bodyguard whilst he gathered evidence against the slave trade.

After meeting Clarkson, Falconbridge published in 1788 An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa,[4] an influential book in the abolitionist movement. In this book, he talked about the trade from when the ships first acquired captives from the African coast, through their treatment during the Middle Passage, to the time they were sold into hereditary bondage in the West Indies[5]

In 1790 Alexander gave verbal evidence before a House of Commons Committee. Many of them were hostile toward him.[6]

Final voyage and death

[edit]

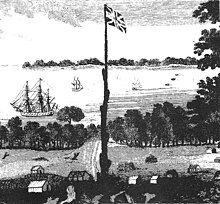

In 1791, Falconbridge was selected by the Anti-Slavery Society to sail to Sierra Leone with his wife Anna Maria; and his brother William,[7] with the intent of reorganising the failed settlement of freed slaves in Granville Town, Sierra Leone. They arrived as passengers on the enslaving ship Duke of Buccleugh. On the voyage out Falconbridge had numerous drunken disputes with Captain John Malean, Duke of Buccleugh's master; Anna Maria would retire to her cabin during these disputes.[8]

Unfortunately, Anna Maria did not share Alexander's idealistic views about the settlement. The couple quarrelled; Falconbridge began to drink excessively, due to marital problems and ailing health and, it would seem, disenchantment with the Sierra Leone Company. A number of Falconbridge's contemporaries were dismissed for vague reasons and it may be that the Company used them as scapegoats. Dismissals included Charles Horwood, brother of Anna Maria, Isaac DuBois (Anna's second husband), and eventually Clarkson himself.

Falconbridge eventually died of drinking a week before Christmas 1792. Henry Thornton, chairman of the Sierra Leone Company, replaced him as the company's commercial agent only hours before his death. The Sierra Leone company refused to acknowledge the claim of his wife Anna Maria for monies owed to her late husband and, perhaps conveniently, the company records went missing.[9]

Legacy

[edit]The colony was eventually named Freetown, and it seems likely that Falconbridge Point in Freetown is named after Alexander Falconbridge. Both Alexander and his brother William, who died in Freetown the previous year, are most likely buried in the Freetown area, though the exact location is not recorded.[10]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Costanzo, Angelo; Equiano, Olaudah (2001). Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. p. 281. ISBN 1-55111-262-0.

- ^ Alston, David (2021), Slaves and Highlanders: Silenced Histories of Scotland and the Caribbean, Edinburgh University Press, p. 19, ISBN 9781474427319

- ^ Falconbridge, Alexander; Falconbridge, Anna Maria; Fyfe, Christopher; DuBois, Isaac (2000). Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone During the Years 1791-1792-1793. Liverpool University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-85323-643-7.

- ^ Taylor, Eric (2006). If We Must Die: Shipboard Insurrections in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-8071-3181-4.

- ^ Falconbridge, Alexander (1973). An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa. New York: AMS Press. ISBN 0-404-00255-2.

- ^ Falconbridge, A.; Falconbridge, A. M.; Fyfe, C.; DuBois, I. (2000). Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone... p. 194. ISBN 9780853236436.

- ^ Smith, Johanna M.; Barros, Carolyn A. (2000). Life-Writings by British Women, 1660–1815: an anthology. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 292. ISBN 1-55553-432-5.

- ^ Mackenzie-Grieve (1941), pp. 215–216.

- ^ Lovejoy (2018).

- ^ Smith & Barros (2000). Life-Writings by British Women, 1660–1815. p. 293. ISBN 9781555534325.

References

[edit]- Lovejoy, Henry B. (2018). Prieto: Yorùbá Kingship in Colonial Cuba during the Age of Revolutions. UNC Press. ISBN 9781469645384.

- Mackenzie-Grieve, Averil. (1941). The Last Years of the English Slave Trade, Liverpool, 1750-1807. Putnam.

External links

[edit]- Alexander Falconbridge (1788) An account of the slave trade on the coast of Africa on the Internet Archive