Alcohol and sex

Alcohol and sex deals with the effects of the consumption of alcohol on sexual behavior.[2] The effects of alcohol are balanced between its suppressive effects on sexual physiology, which will decrease sexual activity, and its suppression of sexual inhibitions.[3] A large portion of sexual assaults involve alcohol consumption by the perpetrator, victim, or both.[4]

Alcohol is a depressant. After consumption, alcohol causes the body's systems to slow down. Often, feelings of drunkenness are associated with elation and happiness but other feelings of anger or depression can arise. Balance, judgment, and coordination are also negatively affected. One of the most significant short term side effects of alcohol is reduced inhibition. Reduced inhibitions can lead to an increase in sexual behavior.[3]

In men

[edit]Low to moderate alcohol consumption is shown to have protective effect for men's erectile function. Several reviews and meta-analyses of existing literature show that low to moderate alcohol consumption significantly decreases erectile dysfunction risk.[5][6][7][8]

Men's sexual behaviors can be affected dramatically by high alcohol consumption. Both chronic and acute alcohol consumption have been shown in most studies [9][10][11] (but not all[12]) to inhibit testosterone production in the testes. This is believed to be caused by the metabolism of alcohol reducing the NAD+/NADH ratio both in the liver and the testes; since the synthesis of testosterone requires NAD+, this tends to reduce testosterone production.[13][14]

As testosterone is critical for libido and physical arousal, alcohol tends to have deleterious effects on male sexual performance. Studies have been conducted that indicate increasing levels of alcohol intoxication produce a significant degradation in male masturbatory effectiveness (MME). This degradation was measured by measuring blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and ejaculation latency.[15] Alcohol intoxication can decrease sexual arousal, decrease pleasureability and intensity of orgasm, and increase difficulty in attaining orgasm.[15]

In women

[edit]In women, the effects of alcohol on libido in the literature are mixed. Some women report that alcohol increases sexual arousal and desire, however, some studies show alcohol lower the physiological signs of arousal.[16] A 2016 study found that alcohol negatively affected how positive the sexual experience was in both men and women.[17] Studies have shown that acute alcohol consumption tends to cause increased levels of testosterone and estradiol.[18][19] Since testosterone controls in part the strength of libido in women, this could be a physiological cause for an increased interest in sex. Also, because women have a higher percentage of body fat and less water in their bodies, alcohol can have a quicker, more severe impact. Women's bodies take longer to process alcohol; more precisely, a woman's body often takes one-third longer to eliminate the substance.[20]

Sexual behavior in women under the influence of alcohol is also different from men. Studies have shown that increased BAC is associated with longer orgasmic latencies and decreased intensity of orgasm.[16] Some women report a greater sexual arousal with increased alcohol consumption as well as increased sensations of pleasure during orgasm. Because ejaculatory response is visual and can more easily be measured in males, orgasmic response must be measured more intimately. In studies of the female orgasm under the influence of alcohol, orgasmic latencies were measured using a vaginal photoplethysmograph, which essentially measures vaginal blood volume.[16]

Psychologically, alcohol has also played a role in sexual behavior. It has been reported that women who were intoxicated believed they were more sexually aroused than before consumption of alcohol.[16] This psychological effect contrasts with the physiological effects measured, but refers back to the loss of inhibitions because of alcohol. Often, alcohol can influence the capacity for a woman to feel more relaxed and in turn, be more sexual. Alcohol may be considered by some women to be a sexual disinhibitor.[16]

Risky sexual behavior

[edit]Some studies have made a connection between hookup culture and substance use.[21] Most students said that their hookups occurred after drinking alcohol.[21][22][23] Frietas stated that in her study, the relationships between drinking and the party scene and between alcohol and hookup culture were "impossible to miss".[24]

Studies suggest that the degree of alcoholic intoxication in young people directly correlates with the level of risky behavior,[25] such as engaging in multiple sex partners.[26]

In 2018, the first study of its kind, found that alcohol and caffeinated energy drinks is linked with casual, risky sex among college-age adults.[27]

Sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy

[edit]

Alcohol intoxication is associated with an increased risk that people will become involved in risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex.[15] Both men,[28] and women,[29] reported higher intentions to avoid using a condom when they were intoxicated by alcohol.

Coitus interruptus, also known as withdrawal, pulling out or the pull-out method, is a method of birth control during penetrative sexual intercourse, whereby the penis is withdrawn from a vagina or anus prior to ejaculation so that the ejaculate (semen) may be directed away in an effort to avoid insemination.[30][31] Coitus interruptus carries a risk of STIs and unintended pregnancy. This risk is especially high during alcohol intoxication because lowered sexual inhibition can make it difficult to withdraw in time.

Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to smoke tobacco,[32] drink alcohol during pregnancy,[33][34] and binge drink during pregnancy,[32] which results in poorer health outcomes.[33] (See also: fetal alcohol spectrum disorder)

Sexual assaults

[edit]Rape is any sexual activity that occurs without the freely given consent of one of the parties involved. This includes alcohol-facilitated sexual assault which is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions,[35] or non-consensual condom removal which is criminalized in some countries (see the map below).

A 2008 study found that rapists typically consumed relatively high amounts of alcohol and infrequently used condoms during assaults, which was linked to a significant increase in STI transmission.[36] This also increases the risk of pregnancy from rape for female victims. Some people turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with emotional trauma after a rape; use of these during pregnancy can harm the fetus.[37]

Alcohol-facilitated sexual assault

[edit]

One of the most common date rape drugs is alcohol,[39][40][41] administered either surreptitiously[42] or consumed voluntarily,[39] rendering the victim unable to make informed decisions or give consent. The perpetrator then facilitates sexual assault or rape, a crime known as alcohol- or drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA).[43][35][44] Many perpetrators use alcohol because their victims often drink it willingly, and can be encouraged to drink enough to lose inhibitions or consciousness.[45] However, sex with an unconscious victim is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions, and some assailants have committed "rapes of convenience" whereby they have assaulted a victim after he or she had become unconscious from drinking too much.[46] The risk of individuals either experiencing or perpetrating sexual violence and risky sexual behavior increases with alcohol abuse,[47] and by the consumption of caffeinated alcoholic drinks.[48][49]

Non-consensual condom removal

[edit]

Non-consensual condom removal, or "stealthing",[50] is the practice of a person removing a condom during sexual intercourse without consent, when their sex partner has only consented to condom-protected sex.[51][52] Purposefully damaging a condom before or during intercourse may also be referred to as stealthing,[53] regardless of who damaged the condom.

Consuming alcohol can be risky in sexual situations. It can impair judgment and make it difficult for both people to give or receive informed sexual consent. However, a history of sexual aggression and alcohol intoxication are factors associated with an increased risk of men employing non-consensual condom removal and engaging in sexually aggressive behavior with female partners.[54][55]

Wartime sexual violence

[edit]The use of alcohol is a documented factor in wartime sexual violence.

For example, rape during the liberation of Serbia was committed by Soviet Red Army soldiers against women during their advance to Berlin in late 1944 and early 1945 during World War II. Serbian journalist Vuk Perišić said about the rapes: "The rapes were extremely brutal, under the influence of alcohol and usually by a group of soldiers. The Soviet soldiers did not pay attention to the fact that Serbia was their ally, and there is no doubt that the Soviet high command tacitly approved the rape."[56]

While there wasn't a codified international law specifically prohibiting rape during World War II, customary international law principles already existed that condemned violence against civilians. These principles formed the basis for the development of more explicit laws after the war,[57] including the Nuremberg Principles established in 1950.

"Beer goggles"

[edit]A study published in 2003 supported the beer goggles hypothesis; however, it also found that another explanation is that regular drinkers tend to have personality traits that mean they find people more attractive, whether or not they are under the influence of alcohol at the time.[58] A 2009 study showed that while men found adult women (who were wearing makeup) more attractive after consuming alcohol, the alcohol did not interfere with their ability to determine a woman's age.[59]

A 2021 study found that bar patrons rated themselves as more attractive towards the end of the night, regardless of their level of intoxication, and that this effect had more to do with motivations to attract a mate. The "closing time effect" was tested in Danish bars, with researchers separating responses based on whether bar patrons had filled out their survey in the afternoon, evening, or night, and finding that people attending the bar at night rated themselves as more attractive than earlier visitors.[60]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

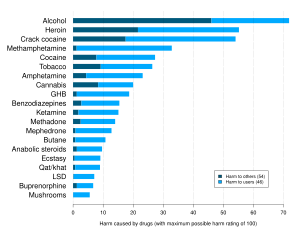

[edit]- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ World Health Organization, Mental Health Evidence and Research Team (2005). Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk Behaviour. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156289-8.

- ^ a b Crowe, LC; George, WH (1989). "Alcohol and human sexuality: Review and integration". Psychological Bulletin. 105 (3): 374–86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.374. PMID 2660179.

- ^ Abbey, Antonia; Zawacki, Tina; Buck, Philip O.; Clinton, A. Monique; McAuslan, Pam (August 18, 2001). "Alcohol and Sexual Assault". Alcohol Research & Health. 25 (1): 43–51. PMC 4484576. PMID 11496965.

- ^ Allen, Mark S; Walter, Emma E (2018). "Health-Related Lifestyle Factors and Sexual Dysfunction: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Research". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 15 (4): 458–475. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.008. PMID 29523476.

- ^ Cheng, J Y W; Ng, E M L; Chen, R Y L; Ko, J S N (2007). "Alcohol consumption and erectile dysfunction: meta-analysis of population-based studies". International Journal of Impotence Research. 19 (4): 343–352. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901556. PMID 17538641.

- ^ Wang, Xiao-Ming; Bai, Yun-Jin; Yang, Yu-Bo; Li, Jin-Hong; Tang, Yin; Han, Ping (2018). "Alcohol intake and risk of erectile dysfunction: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies". International Journal of Impotence Research. 30 (6): 342–351. doi:10.1038/s41443-018-0022-x. PMID 30232467. S2CID 52300588.

- ^ Jiann, Bang-Ping (2010). "Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Risk of Erectile Dysfunction" (PDF). Urol Sci. 21 (4): 163–168. doi:10.1016/S1879-5226(10)60037-1.

- ^ Frias, J; Torres, JM; Miranda, MT; Ruiz, E; Ortega, E (2002). "Effects of acute alcohol intoxication on pituitary-gonadal axis hormones, pituitary-adrenal axis hormones, beta-endorphin and prolactin in human adults of both sexes". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 37 (2): 169–73. doi:10.1093/alcalc/37.2.169. PMID 11912073.

- ^ Mendelson, JH; Ellingboe, J; Mello, NK; Kuehnle, John (1978). "Effects of Alcohol on Plasma Testosterone and Luteinizing Hormone Levels". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2 (3): 255–8. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1978.tb05808.x. PMID 356646.

- ^ Mendelson, JH; Mello, NK; Ellingboe, J (1977). "Effects of acute alcohol intake on pituitary-gonadal hormones in normal human males". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 202 (3): 676–82. PMID 894528.

- ^ Sarkola, T; Eriksson, CJP (2003). "Testosterone Increases in Men After a Low Dose of Alcohol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 27 (4): 682–685. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2003.tb04405.x. PMID 12711931.

- ^ Emanuele, MA; Halloran, MM; Uddin, S; Tentler, JJ; Emanuele, NV; Lawrence, AM; Kelly, MR (1993). "The effects of alcohol on the neuroendocrine control of reproduction". In Zakhari, S (ed.). Alcohol and the Endocrine System. National Institute of Health Publications. pp. 89–116. NIH Pub 93-3533.

- ^ Ellingboe, J; Varanelli, CC (1979). "Ethanol inhibits testosterone biosynthesis by direct action on Leydig cells". Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology. 24 (1): 87–102. PMID 219455.

- ^ a b c Halpernfelsher, B; Millstein, S; Ellen, J (1996). "Relationship of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: A review and analysis of findings". Journal of Adolescent Health. 19 (5): 331–6. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00024-9. PMID 8934293.

- ^ a b c d e Beckman, LJ; Ackerman, KT (1995). "Women, alcohol, and sexuality". Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 12: 267–85. doi:10.1007/0-306-47138-8_18. ISBN 978-0-306-44921-5. PMID 7624547.

- ^ Cooper, M. Lynne; O'Hara, Ross E.; Martins, Jorge (2015-07-16). "Does Drinking Improve the Quality of Sexual Experience?: Sex-Specific Alcohol Expectancies and Subjective Experience on Drinking Versus Sober Sexual Occasions". AIDS and Behavior. 20 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1136-5. ISSN 1090-7165. PMID 26179171. S2CID 41604244.

- ^ Sarkola, T; Fukunaga, T; Mäkisalo, H; Peter Eriksson, CJ (2000). "Acute Effect of Alcohol on Androgens in Premenopausal Women". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 35 (1): 84–90. doi:10.1093/alcalc/35.1.84. PMID 10684783.

- ^ Ellingboe, J (1987). "Acute effects of ethanol on sex hormones in non-alcoholic men and women". Alcohol and Alcoholism Supplement. 1: 109–16. PMID 3122772.

- ^ Crowe, LC; George, WH (1989). "Alcohol and human sexuality: Review and integration". Psychological Bulletin. 105 (3): 374–86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.374. PMID 2660179.

- ^ a b Garcia, Justin R.; Reiber, Chris; Massey, Sean G.; Merriwether, Ann M. (February 2013). "Sexual Hook-up Culture". Monitor on Psychology. Vol. 44, no. 2. American Psychological Association. p. 60. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- ^ Fielder, R. L.; Carey, M. P. (2010). "Predictors and Consequences of Sexual "Hookups" Among College Students: A Short-Term Prospective Study". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 39 (5): 1105–1119. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. PMC 2933280. PMID 19130207.

- ^ Lewis, M. A.; Granato, H.; Blayney, J. A.; Lostutter, T. W.; Kilmer, J. R. (2011). "Predictors of Hooking Up Sexual Behavior and Emotional Reactions Among U.S. College Students". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 41 (5): 1219–1229. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. PMC 4397976. PMID 21796484.

- ^ Freitas 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Paul EL, McManus B, Hayes A (2000). "'Hookups': Characteristics and Correlates of College Students' Spontaneous and Anonymous Sexual Experiences". Journal of Sex Research. 37 (1): 76–88. doi:10.1080/00224490009552023.

- ^ Santelli, JS; Brener, ND; Lowry, R; Bhatt, A; Zabin, LS (November 1998). "Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults". Family Planning Perspectives. 30 (6): 271–5. doi:10.2307/2991502. JSTOR 2991502. PMID 9859017.

- ^ Ball, NJ; Miller, KE; Quigley, BM; Eliseo-Arras, RK (April 2021). "Alcohol Mixed With Energy Drinks and Sexually Related Causes of Conflict in the Barroom". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 36 (7–8): 3353–3373. doi:10.1177/0886260518774298. PMID 29779427. S2CID 29150434.

- ^ Neilson, EC; Marcantonio, TL; Woerner, J; Leone, RM; Haikalis, M; Davis, KC (March 2024). "Alcohol intoxication, condom use rationale, and men's coercive condom use resistance: The role of past unintended partner pregnancy". Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 38 (2): 173–184. doi:10.1037/adb0000956. PMC 10932814. PMID 37707467.

- ^ Davis, KC; Masters, NT; Eakins, D; Danube, CL; George, WH; Norris, J; Heiman, JR (January 2014). "Alcohol intoxication and condom use self-efficacy effects on women's condom use intentions". Addictive Behaviors. 39 (1): 153–8. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.019. PMC 3940263. PMID 24129265.

- ^ Rogow D, Horowitz S (1995). "Withdrawal: a review of the literature and an agenda for research". Studies in Family Planning. 26 (3): 140–53. doi:10.2307/2137833. JSTOR 2137833. PMID 7570764., which cites:

- Population Action International (1991). "A Guide to Methods of Birth Control". Briefing Paper No. 25, Washington, D. C.

- ^ Casey FE (20 March 2024). Talavera F, Barnes AD (eds.). "Coitus interruptus". Medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ a b Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML (April 1999). "Effects of smoking during pregnancy. Five meta-analyses". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 16 (3): 208–215. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00089-0. PMID 10198660. S2CID 33535194.

- ^ a b Eisenberg L, Brown SH (1995). The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0-309-05230-6.

- ^ "Intended and Unintended Births in the United States: 1982–2010" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. July 24, 2012. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ a b Hall JA, Moore CB (July 2008). "Drug facilitated sexual assault—a review". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 15 (5): 291–7. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.12.005. PMID 18511003.

- ^ Davis KC, Schraufnagel TJ, George WH, Norris J (September 2008). "The use of alcohol and condoms during sexual assault". American Journal of Men's Health. 2 (3): 281–290. doi:10.1177/1557988308320008. PMC 4617377. PMID 19477791.

- ^ Price S (2007). Mental Health in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-443-10317-9. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ ElSohly MA, Salamone SJ (1999). "Prevalence of drugs used in cases of alleged sexual assault". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 23 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1093/jat/23.3.141. PMID 10369321.

- ^ a b "Alcohol Is Most Common 'Date Rape' Drug". Medicalnewstoday.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Schwartz RH, Milteer R, LeBeau MA (June 2000). "Drug-facilitated sexual assault ('date rape')". Southern Medical Journal. 93 (6): 558–61. doi:10.1097/00007611-200093060-00002. PMID 10881768.

- ^ Holstege CP, Saathoff GB, Neer TM, Furbee RB, eds. (25 October 2010). Criminal poisoning: clinical and forensic perspectives. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 232. ISBN 978-0-7637-4463-2.

- ^ Lyman MD (2006). Practical drug enforcement (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. p. 70. ISBN 0849398088.

- ^ Thompson KM (January 2021). "Beyond roofies: Drug- and alcohol-facilitated sexual assault". JAAPA. 34 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000723940.92815.0b. PMID 33332834.

- ^ Beynon CM, McVeigh C, McVeigh J, Leavey C, Bellis MA (July 2008). "The involvement of drugs and alcohol in drug-facilitated sexual assault: a systematic review of the evidence". Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 9 (3): 178–88. doi:10.1177/1524838008320221. PMID 18541699. S2CID 27520472.

- ^ Date Rape. Survive.org.uk (2000-03-20). Retrieved on June 1, 2011.

- ^ "Date Rape". Survive.org.uk. 20 March 2000. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Chersich MF, Rees HV (January 2010). "Causal links between binge drinking patterns, unsafe sex and HIV in South Africa: its time to intervene". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 21 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2000.009432. PMID 20029060. S2CID 3100905.

- ^ "Consumption of alcohol/energy drink mixes linked with casual, risky sex". ScienceDaily.

- ^ Ball NJ, Miller KE, Quigley BM, Eliseo-Arras RK (April 2021). "Alcohol Mixed With Energy Drinks and Sexually Related Causes of Conflict in the Barroom". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 36 (7–8): 3353–3373. doi:10.1177/0886260518774298. PMID 29779427. S2CID 29150434.

- ^ Hatch J (21 April 2017). "Inside The Online Community Of Men Who Preach Removing Condoms Without Consent". Huffington Post. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Chesser B, Zahra A (22 May 2019). "Stealthing: a criminal offence?". Current Issues in Criminal Justice. 31 (2). Sydney Law School: 217–235. doi:10.1080/10345329.2019.1604474. S2CID 182850828. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Brodsky A (2017). "'Rape-Adjacent': Imagining Legal Responses to Nonconsensual Condom Removal". Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. 32 (2). SSRN 2954726.

- ^ Michael N (27 April 2017). "Some call it 'stealthing,' others call it sexual assault". CNN.

- ^ Davis KC, Danube CL, Neilson EC, Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, George WH, Kajumulo KF (January 2016). "Distal and Proximal Influences on Men's Intentions to Resist Condoms: Alcohol, Sexual Aggression History, Impulsivity, and Social-Cognitive Factors". AIDS and Behavior. 20 (Suppl 1): S147–S157. doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1132-9. PMC 4706816. PMID 26156881.

- ^ Davis KC (October 2010). "The influence of alcohol expectancies and intoxication on men's aggressive unprotected sexual intentions". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (5): 418–428. doi:10.1037/a0020510. PMC 3000798. PMID 20939645.

- ^ Welle (http://www.dw.com), Deutsche. "'Njemačke žene nisu silovali samo sovjetski vojnici' | DW | 02.03.2015". DW.COM (in Croatian). Retrieved 2022-07-02.

- ^ "Rule 93. Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence". ihl-databases.icrc.org. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ Jones, BT; Jones, BC; Thomas, AP; Piper, J (2003). "Alcohol consumption increases attractiveness ratings of opposite-sex faces: A possible third route to risky sex". Addiction. 98 (8): 1069–75. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00426.x. PMID 12873241.

- ^ Egan, V; Cordan, G (2009). "Barely legal: Is attraction and estimated age of young female faces disrupted by alcohol use, make up, and the sex of the observer?". British Journal of Psychology. 100 (2): 415–27. doi:10.1348/000712608X357858. PMID 18851766.

- ^ Ellwood, Beth (2021-09-22). "Bar patrons feel more attractive the closer it is to closing time, regardless of how much alcohol they've had". PsyPost. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

Sources

[edit]- Freitas, Donna (2013). The End of Sex: How Hookup Culture is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Intimacy. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00215-3.

- Price, Sally (2007). Mental Health in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-443-10317-9. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Abbey, A; Zawacki, T; Buck, PO; Clinton, AM; McAuslan, P (2001). "Alcohol and Sexual Assault" (PDF). Alcohol Health & Research. 25 (1): 43–51. PMC 4484576. PMID 11496965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-30.

- Lyness, D (February 2009). "Date Rape". KidsHealth.org. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- Malatesta, V; Pollack, R; Crotty, T; Peacock, L (1982). "Acute alcohol intoxication and female orgasmic response". Journal of Sex Research. 18 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/00224498209551130.

- Malatesta, V; Pollack, R; Wilbanks, WA; Adams, H (1979). "Alcohol effects on the orgasmic-ejaculatory response in human males". Journal of Sex Research. 15 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1080/00224497909551027. PMID 491549.

- Ridberg, R (2004). Spin the Bottle: Sex, Lies & Alcohol. Media Education Foundation. ISBN 978-1-893521-89-6.