Alanine racemase

| alanine racemase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alanine racemase homotetramer, Oenococcus oeni | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 5.1.1.1 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9024-06-0 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Ala_racemase_N | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

the 1.45Å a crystal structure of alanine racemase from a pathogenic bacterium, pseudomonas aeruginosa, contains both internal and external aldimine forms | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Ala_racemase_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01168 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0036 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001608 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00332 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1sft / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Ala_racemase_C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Ala_racemase_C | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00842 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR011079 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00332 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1sft / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In enzymology, an alanine racemase (EC 5.1.1.1) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

- L-alanine D-alanine

Hence, this enzyme has one substrate, L-alanine, and one product, D-alanine.

This enzyme belongs to the family of isomerases, specifically those racemases and epimerases acting on amino acids and derivatives. The systematic name of this enzyme class is alanine racemase. This enzyme is also called L-alanine racemase. This enzyme participates in alanine and aspartate metabolism and D-alanine metabolism. It employs one cofactor, pyridoxal phosphate. At least two compounds, 3-Fluoro-D-alanine and D-Cycloserine are known to inhibit this enzyme.

The D-alanine produced by alanine racemase is used for peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Peptidoglycan is found in the cell walls of all bacteria, including many which are harmful to humans. The enzyme is absent in higher eukaryotes but found everywhere in prokaryotes, making alanine racemase a great target for antimicrobial drug development.[1] Alanine racemase can be found in some invertebrates.[2]

Bacteria can have one (alr gene) or two alanine racemase genes. Bacterial species with two genes for alanine racemase have one that is continually expressed and one that is inducible, which makes it difficult to target both genes for drug studies. However, knockout studies have shown that without the alr gene being expressed, the bacteria would need an external source of D-alanine in order to survive. Therefore, the alr gene is a feasible target for antimicrobial drugs.[1]

Alanine racemase is the only known protein, as of 2002, to contain a left-handed α-helix of 5 amino acids, the longest left-handed α-helix found up until at that point.[3]

Structural studies

[edit]To catalyze the interconversion of D and L alanine, Alanine racemase must position residues capable of exchanging protons on either side of the alpha carbon of alanine. Structural studies of enzyme-inhibitor complexes suggest that Tyrosine 265 and Lysine 39 are these residues. The alpha-proton of the L-enantiomer is oriented toward Tyr265 and the alpha proton of the D-enantiomer is oriented toward Lys39 (Figure 1).

The distance between the enzyme residues and the enantiomers is 3.5 Å and 3.6 Å respectively.[4] Structural studies of enzyme complexes with a synthetic L-alanine analog, a tight binding inhibitor [5] and propionate [6] further validate that Tyr265 and Lys39 are catalytic bases for the reaction,.[5][7]

The PLP-L-Ala and PLP-D-Ala complexes are almost superimposability.[4] The regions that do not overlap are the arms connected the pyridine ring of PLP and the alpha carbon of alanine. An interaction between both the phosphate oxygen and pyridine nitrogen atoms to the 5’phosphopyridoxyl region of PLP-Ala probably creates tight binding to the enzyme.[4]

The structure of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus (Geobacillus stearothermophilus) was determined by X-ray crystallography to a resolution of 1.9 A.[7] The alanine racemase monomer is composed of two domains, an eight-stranded alpha/beta barrel at the N terminus, and a C-terminal domain essentially composed of beta-strand. A model of the two domain structure is shown in Figure 2. The N-terminal domain is also found in the PROSC (proline synthetase co-transcribed bacterial homolog) family of proteins, which are not known to have alanine racemase activity. The pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) cofactor lies in and above the mouth of the alpha/beta barrel and is covalently linked via an aldimine linkage to a lysine residue, which is at the C terminus of the first beta-strand of the alpha/beta barrel.

Proposed mechanism

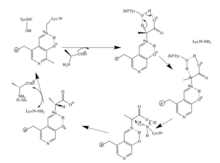

[edit]Reaction mechanisms are difficult to fully prove by experiment. The traditional mechanism attributed to an alanine racemase reaction is that of a two-base mechanism with a PLP-stabilized carbanion intermediate. PLP is used as an electron sink stabilize the negative charge resulting from the deprotonation of the alpha carbon. The two based mechanism favors reaction specificity compared to a one base mechanism. The second catalytic residue is pre-positioned to donate a proton quickly after a carbanionic intermediate is formed and thus reduces the chance of alternative reactions occurring. There are two potential conflicts with this traditional mechanism, as identified by Watanabe et al. First, Arg219 forms a hydrogen bond with pyridine nitrogen of PLP.[7] The arginine group has a pKa of about 12.6 and is therefore unlikely to protonate the pyridine. Normally in PLP reactions an acidic amino acid residue such as a carboxylic acid group, with a pKa of about 5, protonates the pyridine ring.[8] The protonation of the pyridine nitrogen allows the nitrogen to accept additional negative charge. Therefore, due to the Arg219, the PLP-stabilized carbanion intermediate is less likely to form. Another problem identified was the need for another basic residue to return Lys39 and Tyr265 back to their protonated and unprotonated forms for L-alanine and vice versa for D-alanine. Watanabe et al. found no amino acid residues or water molecules, other than the carboxylate group of PLP-Ala, to be close enough (within 4.5A) to protonate or deprotonate Lys or Tyr. This is shown in Figure 3.[4]

Based on the crystal structures of N-(5’-phosphopyridoxyl) L- alanine (PKP-L-Ala ( and N-(5’-phosphopyridoxyl) D-alanine (PLP-D-Ala)

Watanabe et al. proposed an alternative mechanism in 2002, as seen in the figure 4. In this mechanism the carboxylate oxygen atoms of PLP-Ala directly participates in catalysis by mediating proton transfer between Lys39 and Tyr265. The crystallization structure identified that the carboxylate oxygen of PLP-L-Ala to the OH of Tyr265 was only 3.6A and the carboxylate oxygen of PLP-L-Ala to the nitrogen of Lys39 was only 3.5A. Therefore, both were close enough to cause a reaction.

This mechanism is supported by mutations of Arg219. Mutations changing Arg219 to a carboxylate result in a quinonoid intermediate being detected whereas none was detected with arginine.[9] The arginine intermediate has much more free energy, is more unstable, than the acidic residue mutants.[8] The destabilization of the intermediate promotes specificity of the reaction,.[9][10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Milligan Daniel L.; et al. (2007). "The Alanine Racemase of Mycobacterium smegmatis Is Essential for Growth in the Absence of D-Alanine". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (22): 8381–8386. doi:10.1128/jb.01201-07. PMC 2168708. PMID 17827284.

- ^ Abe, H; Yoshikawa, N; Sarower, M. G.; Okada, S (2005). "Physiological function and metabolism of free D-alanine in aquatic animals". Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 28 (9): 1571–7. doi:10.1248/bpb.28.1571. PMID 16141518.

- ^ Hovmöller, Sven; Zhou, Tuping; Ohlson, Tomas (May 2002). "Conformations of amino acids in proteins". Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 58 (Pt 5): 768–776. doi:10.1107/s0907444902003359. ISSN 0907-4449. PMID 11976487.

- ^ a b c d Watanabe, A., Yoshimura, T., Mikami, B., Hayashi, H., Kagamiyama, H., Esaki, N. (2002) Reaction Mechanism of Alanine Racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus: X-ray crystallographic studies of the enzyme bound within -(5’-phosphopyridoxyl)alanine Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 19166-19172.

- ^ a b Stamper, G. F., Morollo, A. A., and Ringe, D. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 10438 –10445

- ^ Morollo, A. A., Petsko, G. A., and Ringe, D. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 3293–3301

- ^ a b c Shaw, J. P., Petsko, G. A., and Ringe, D. (1997) Determination of the Structure of Alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus at 1.9-A Resolution Biochemistry 36, 1329–1342

- ^ a b Toney, Michael D. (2004) Reaction specificity in pyridoxal phosphate enzymes, Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 433, 279-287.

- ^ a b Sun S., Toney, M.D. (1998) Evidence for a Two-Base Mechanism Involving Tyrosine-265 from Arginine-219 Mutants of Alanine Racemase Biochemistry 38, 4058-4065

- ^ Rubinstein, A., Major, D. T. (2010) Understanding Catalytic Specificity in Alanine Racemase from Quantum Mechanical Molecular Mechanical Simulations of the Arginine 210 Mutant Biochemistry 49, 3957-3963.

Further reading

[edit]- MARR AG, WILSON PW (1954). "The alanine racemase of Brucella abortus". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 49 (2): 424–33. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(54)90211-8. PMID 13159289.

- Wood WA (1955). [25] Amino acid racemases. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 2. pp. 212–217. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(55)02189-7. ISBN 9780121818029.

- WOOD WA, GUNSALUS IC (1951). "D-Alanine formation; a racemase in Streptococcus faecalis". J. Biol. Chem. 190 (1): 403–16. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56082-8. PMID 14841188.