Soul food

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

Soul food is the ethnic cuisine of African Americans.[1][2] Originating in the American South from the cuisines of enslaved Africans transported from Africa through the Atlantic slave trade, soul food is closely associated with the cuisine of the Southern United States.[3] The expression "soul food" originated in the mid-1960s when "soul" was a common word used to describe African-American culture.[4] Soul food uses cooking techniques and ingredients from West African, Central African, Western European, and Indigenous cuisine of the Americas.[5]

The cuisine was initially denigrated as low quality and belittled because of its origin. It was seen as low-class food, and African Americans in the North looked down on their Black Southern compatriots who preferred soul food (see the Great Migration).[6] The concept evolved from describing the food of slaves in the South, to being taken up as a primary source of pride in the African American community even in the North, such as in New York City, Chicago and Detroit.[7][8]

Soul food historian Adrian Miller said the difference between soul food and Southern food is that soul food is intensely seasoned and uses a variety of meats to add flavor to food and adds a variety of spicy and savory sauces. These spicy and savory sauces add robust flavor. This method of preparation was influenced by West African cuisine where West Africans create sauces to add flavor and spice to their food. Black Americans also add sugar to make cornbread, while "white southerners say when you put sugar in corn bread, it becomes cake"[9]. European immigrants seasoned and flavored their food using salt, pepper, and spices. African Americans add more spices, and hot and sweet sauces to increase the spiciness, or heat of their food.[10] Bob Jeffries, the author of Soul Food Cookbook, said the difference between soul food and Southern food is: "While all soul food is Southern food, not all Southern food is soul. Soul food cooking is an example of how really good Southern [African-American] cooks cooked with what they had available to them."[11]

Impoverished White and Black people in the South cooked many of the same dishes stemming from Southern cooking traditions, but styles of preparation sometimes varied. Certain techniques popular in soul and other Southern cuisines (i.e., frying meat and using all parts of the animal for consumption) are shared with cultures all over the world.[12]

Etymology

[edit]

The earliest use of the word "soul food" to describe a type of cuisine is found in a 1909 published memoir of a former slave named Thomas L. Johnson. Johnson described a church service where the congregation was served food. He wrote: "There are some, when preaching, only preach three-quarters of the truth, or less, when serving up dishes of soul-food to suit the palates of those they must please."[13] The term soul food became popular during the 1960s and 1970s in the midst of the Black Power movement.[14] One of the earliest written uses of the term is found in The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which was published in 1965.[15] LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) published an article entitled "Soul Food" and was one of the key proponents for establishing the food as a part of the Black American identity.[16] Those who had participated in the Great Migration found within soul food a reminder of the home and family they had left behind after moving to unfamiliar northern cities. Soul food restaurants were Black-owned businesses that served as neighborhood meeting places where people socialized and ate together.[17][18][19] According to author Laretta Henderson, middle-class African Americans embrace their "blackness" by preparing and eating soul food. Henderson wrote:[20]

In its culinary incarnation, "soul food" was associated with a shared history of oppression and inculcated, by some, with cultural pride. Soul food was eaten by the bondsmen. It was also the food former slaves incorporated into their diet after emancipation. Therefore, during the 1960s, middle-class blacks used their reported consumption of soul food to distance themselves from the values of the white middle class, to define themselves ethnically, and to align themselves with lower-class blacks. Irrespective of political affiliation or social class, the definition of "blackness", or "soul", became part of everyday discourse in the black community.

This style of cooking is celebrated in the month of June, called National Soul Food month.[21]

History

[edit]Transatlantic slave trade

[edit]

During the period of the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved people ate African foods aboard slave ships. These included rice, millet, okra, black-eyed peas, yams, and legumes such as kidney beans and lima beans. These crops were brought to North America and became a staple in Southern cuisine.[23][24] One enslaved African aboard a slave ship recalled later that all they ate were yams on the voyage from Africa to Charleston, South Carolina.[25] Slave ships were provisioned with African vegetables, fruits, and animals to feed the enslaved people bound in chains below the ships' decks. These items were later planted and used in the New World for food and as cash crops. The introduction of African plants to the Americas that shaped American cuisine was part of what is called the Columbian exchange.[26][27] Researchers from Mercer University Libraries said: "The foods selected to bring to America were brought over for specific reasons. 'They all remain palatable long after harvesting and were thus ideal for use on the slow voyage from Africa. Secondly, they are all the edible parts of plants that thrive in the American South, and therefore they flourished once they had been planted hopefully by the slave in the garden space allotted to him on his owner's plantation'".[28] Another way rice, okra, and millet came to North America was by enslaved African women on slave ships hiding the seeds of rice, okra, and millet in their braided hair as a precaution against an unknown future in the new land where they would be forced to work.[29][30]

The guineafowl is a bird indigenous to Africa imported to the Americas by way of the slave trade; the bird was brought by the Spanish to the Caribbean, and introduced to the South of what is now the United States in the early 16th century. Guinea fowl became a source of meat for enslaved Black Americans and eventually part of the subsistence culture of the whole region.[25] On American plantations, enslaved people consumed the eggs of the guinea fowl, as well as cooking the meat with rice like their West-Central African forebears. Enslaved Africans in the South continued to prepare their traditional dishes of guinea fowl and plant foods native to West and Central Africa. They adapted European and Native American foods and cooking methods to create new recipes that were passed down orally in Black families and later published in African-American cookbooks by the end of the American Civil War.[31][32][33]

Slavery

[edit]

Soul food recipes have pre-slavery influences, as West African and European foodways were adapted to the environment of the region.[3][34] Soul food originated in the home cooking of the rural Southern United States or the "Deep South" during the time of slavery, using locally gathered or raised foods and other inexpensive ingredients.[35][36] Rabbits, squirrels, and deer were often hunted for meat. Fish, frogs, crawfish, turtles, shellfish, and crab were often collected from fresh waters, salt waters, and marshes.[37][38] Soul food cookery began when African American/Black American enslaved people learned to make do with what they were given to eat by their enslavers: leftovers and the undesirable parts of animals such as ham hocks, hog jowls and pigs' feet, ears, skin, and intestines, which white plantation owners did not eat.[39][40] Soul food was created by enslaved African Americans, who created meals out of minimal ingredients.[41] Slaves combined their knowledge of West-Central African cooking methods with techniques borrowed from Native Americans and Europeans, thus creating soul food.[42][9]

Pork and corn were two staple items in the Southern United States for both slave owners and slaves. Many of the foods integral to the cuisine originated in the limited foodstuffs that poor southern subsistence farmers had at hand. This in turn was reflected in the rations given to enslaved people their enslavers. Enslaved people were typically given a peck of cornmeal and 3–4 pounds of pork per week, and those rations formed the basis of African American soul food.[43] Most enslaved people needed to consume a high-calorie diet to replenish the calories spent working long days in the fields or performing other physically arduous tasks.[44] The slave owners would have smoked ham and corn pudding while the enslaved were left with the offal.[45][46] The leftovers and scraps from meals cooked for the "big houses" (plantation houses) were called "juba" by the enslaved. They were put in troughs on Sundays for the slaves to eat. The term "juba" occurs in numerous African languages, and folk knowledge records that early on it had the meaning of "little bits" of food.[47][48]

Archaeological and historical research concerning slave cabins in the Southern United States indicates that enslaved African Americans used bowls more often than flatware and plates, suggesting that they primarily made stews and "gumbo" for meals, using local ingredients gathered in nature, vegetables grown in their gardens, and leftover animal scraps rejected by their enslavers. This process allowed enslaved people to create new dishes, for which they developed a variety of ways to season and add spice using hot sauces they prepared. The research shows that white plantation families more often used plates and flatware, indicating that they ate meals consisting of individual cuts of meats and vegetables that were not blended into one dish like the stews made by enslaved people. Enslaved people living on plantations located along the Atlantic coast developed a diversity of foodways enabled by their access to seafood.[49]

During slavery times, Gullah people in the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia practiced a fishing culture that came from West Africa and made canoes similar in appearance to the ones in sub-Saharan Africa. Gullah people passed down their fishing traditions and prepared meals of fish using local ingredients from the region, developing fish dishes that are still a part of Gullah culture. Author Amy Lynne Young's research at the Mary Plantation in Louisiana showed the differences in foodways between enslaved people living inland versus those living along the Atlantic coast. Families in coastal areas had access to a variety of meats from land and sea animals, especially those who lived on the coastlines and barrier Sea Islands. Inland slaves' choices of meats were limited, consisting of game such as rabbit and squirrel, farm chickens, pigs, and leftover animal scraps. Vegetables were locally gathered or grown in their gardens. Young suggests enslaved people living along the coast consequently had a more diverse diet than inland slaves. This demonstrates regional styles of cooking soul food based on local ingredients.[50][51][52]

Frederick Douglass said in his autobiography that because enslaved people living on the Eastern shore of Maryland near the Choptank River received the bare minimum in food from their enslavers, they fished for food to supplement their diet, catching turtles, fish, and eels. Douglass wrote: "The men and women slaves received, as their monthly allowance of food, eight pounds of pork, or its equivalent in fish, and one bushel of corn meal". Another way they supplemented their diet was by growing vegetable gardens; they grew corn, potatoes, peas, beans, herbs, and melons. They did not have fat or cooking oil to cook their food.[53][54] Slaveholders in Dorchester County, Maryland rarely fed their slaves. To supplement their poor diets, enslaved people in Dorchester fished for food in the Choptank River and hunted game on land. The animals they caught for food included rabbit, turtle, duck, goose, turkey, pigeon, woodpecker, possum, raccoon, skunk, deer, and muskrat. They cooked vegetables such as okra, corn, leafy greens, and sweet potatoes that they grew in their gardens. From these various food sources enslaved people created their meals.[55]

Researchers at St. Mary's County Library located in Maryland documented an African American muskrat recipe. "Skin and disjoint the animal. Soak it in salted or vinegar water for two hours. Put the pieces in a pan of water, and parboil until slightly tender, but not real done. Dust in a mixture of seasoned flour, salted and peppered to taste, and fry in hot fat until golden brown." Black Americans in St. Mary's County created recipes during slavery that were passed down orally in their families.[56] To add heat and flavor to seafood dishes, enslaved and free Africans in Baltimore and the Chesapeake region of Maryland grew fish peppers in their gardens.[57][58][59] After national emancipation many African Americans got into the seafood industry. By 1864, almost half of all watermen in Maryland were former slaves. They became skilled in netting shrimp, gathering oysters, and fishing.[60] During the American Civil War, some enslaved people in Maryland ate clabber milk, fish, and cornbread.[61] After the war, Maryland became known for its crabbing industry, and Maryland deep-fried crab cakes became a part of soul food cuisine.[62]

Enslaved fishermen in Virginia caught fish to feed their families and the slave community. The Encyclopedia of Virginia said if the history of free and enslaved Black fishermen: "Enslaved workers also received fish considered undesirable by whites, such as garfish, whose red flesh Niemcewicz explained 'is little esteemed, serving only as food for negroes', and black catfish, which held less appeal for whites than white catfish, which was 'considered excellent'. Enslaved workers also fished in their time off to supplement their rations."[63][64] At George Washington's residential plantation in Virginia, Mount Vernon, enslaved cooks there prepared corn meal pancakes, "hoe cakes", individual cuts of meat, and seasoned cooked vegetables for the Washington family, while the enslaved people primarily ate corn meal and salted fish.[65]

The diet of slaves in Virginia generally included meat from farm animals, vegetables, blackberries, walnuts, and seafood. Historical research at the Burroughs plantation in Franklin County, Virginia by the National Park Service showed that enslaved people there had a diet of cornbread, pork, chicken, sweet potatoes, and boiled corn for breakfast. Along the coast, enslaved people ate oysters and seafood. Booker T. Washington was born enslaved in Franklin County, Virginia in 1856 and wrote an autobiography titled, The Story of My Life and Work and Up from Slavery, that described the diet he grew up with as an enslaved child. Washington's mother was an enslaved plantation cook who prepared meals for the white families.[66]

Booker T. Washington's mother cooked over an open fireplace or in skillets and pots. Washington, his mother, and siblings ate out of pots and skillets while white families ate from plates and flatware using forks and spoons. His mother prepared one-pot meals for her family using local meats, vegetables, nuts, and berries, combining all the ingredients in a pot to make a stew. This way of cooking is still done in West Africa and continued in the Southern United States with enslaved families.[67] Enslaved people at the Burroughs plantation had a variety of vegetables with which to make stews; they were: "Asparagus, beets, beans, black-eyed peas, carrots, cabbage, cucumbers, garden peas, Irish potatoes, kale, lettuce, lima beans, muskmelons, okra, onions, peppers, radishes, tomatoes, turnips, and watermelons would be planted, ripened, and harvested from spring through fall".[66]

According to Chambers's research, Igbo Africans influenced the foodways of Black Americans in Virginia. During the slave trade, about 30,000 Igbo people were imported from Igboland to Virginia. Igbo people in West Africa ate yams, okra, poultry, goats, and fished for their food. Okra, yams, black-eyed peas, and other African foods were brought to Virginia and enslaved Igbo people cooked these foods and prepared stews as one-pot meals. Enslaved people fished for food in the Chesapeake Bay and prepared seafood meals. In Virginia's nearby creeks and rivers, slaves caught catfish, crayfish, perch, herring, and turtles for food.[68][69] White plantation owners in Virginia rarely provided food to feed their slaves. To supplement their diets, enslaved people relied on Igbo methods such as hunting, fishing, and foraging for food and prepared meals that were influenced by Igbo culture. Chambers wrote: "Slave owners stinted the slaves, throwing the people back onto their own resourcefulness for sustenance. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, masters provided slaves with only the barest necessities. Weekly or monthly rations consisted of salt fish and/ or pork, corn or cornmeal, and salt and perhaps molasses. The largest plantation holders usually doled out salted herring as well as smoked pork and corn, which the slaves pounded and mixed with beans and boiled into hominy".[70]

A few enslaved chefs had some degree of autonomy because of their cooking skills, such as Hercules Posey and James Hemings. Hercules Posey was the enslaved cook for George Washington at Mount Vernon in Virginia. Posey's dishes were so popular among elite White families that he had quasi-freedom to leave the house on his own and earn money selling leftovers. According to historians, the dishes Posey made were influenced by West African, European, and Native American foodways. He created dishes of veal, roast beef, and duck, along with puddings and jellies prepared in a way not unlike that of other chefs, but creating his own sauces and flavors. Posey was never given his freedom, and eventually escaped from slavery.[71][72] James Hemings (brother of Sally Hemings) was born enslaved in colonial Virginia and was the head chef for Thomas Jefferson. Hemings combined African, French, and Native American food traditions. While enslaved, Hemings traveled to Paris, France with Jefferson, where he trained under French chefs and learned how to make macaroni pie (today called macaroni and cheese). Hemings introduced and popularized macaroni and cheese in the United States; it later became a common side item in soul food dishes in Black communities.[73][74]

Sesame is an African crop that was brought to South Carolina in 1730 during the slave trade. Thomas Jefferson noted how enslaved people prepared stews, baked breads, boiled their greens with sesame seeds, and made sesame pudding. Slaves ate sesame raw, toasted, and boiled. It was used as an ingredient for baked breads in colonial America and is still used in the present day.[23]

Some slaves grew herbs in their gardens to add flavor to their food.[75] Other cooking techniques were boiling and simmering food in an earthenware or iron pot known as colonoware.[76] Salt was used to preserve meats for weeks until consumption.[77] To sweeten their food and beverages, slaves used molasses. They also made blackstrap molasses, a very dark molasses with robust flavor, by cooking the juice of sugarcane low and slow. Other sweet sauces created and used by slaves were sorghum syrup, similar to molasses, made by cooking the juice of the sorghum plant. Sorghum seeds came from West Africa by way of the transatlantic slave trade and were grown by enslaved people on plantations in the New World and used to make sweet sauces.[78][79]

According to research by scholars at Mercer University, white plantation families initially refused to eat African foods prepared by their slaves, although in many plantation kitchens enslaved African women were the primary cooks. These women passed down cultural knowledge of cooking techniques to the children. Older slave women were preferred as cooks by white plantation families because they were seen as nonthreatening, knowledgeable, and skilled in cooking. Time spent in the kitchen was time that enslaved mothers could spend bonding with their children and teaching them about life, culture, and foodways. In African societies and during slavery, women were the primary cooks. The role of enslaved Black women in the kitchen and as mothers led to racist stereotypes portraying them as Mammys.[80][81]

Slave narratives revealed continued African methods of cooking, heating, and seasoning food. Enslaved people roasted and heated their foods using ashes from fire pits, a traditional cooking method in Africa. This method was passed down orally in Black families in the Antebellum South, and slave narratives describe how slaves cooked food this way. The word "ash" was appended to the name of some of the food thus prepared, as in "ash cake" and "ash roasted potatoes". Enslaved people placed food directly on hot ashes or coals to roast or bake their foods. Pots and pans were also placed on top of hot ashes and coals to cook food. Some slaves heated or cooked their foods by putting them on leaves placed on top of the hot ashes. A former slave, Betty Curlett from Arkansas, told of roasting her potatoes on hot ashes: "They cooked a washpot full of peas for a meal or two and roasted potatoes around the pot in the ashes."[82]

Some slaves did not receive enough food from their enslavers as some slaves starved and consequently were malnourished. House slaves and field slaves had different diets. House slaves ate the leftovers they prepared for white plantation families such as individual cuts from meats like chicken, turkey, or fish, along with pies and seasoned vegetables. Slaves working in the field ate leftover animal scraps, offal, and whatever food they could find in their environment. Some field slaves rarely ate regular hearty meals. Historian John Blassingame's book published in 1972, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South, was researched from a collection of slave narratives. According to Blassingame's research, some enslaved people received the bare minimum in food and had to supplement their diets by hunting, fishing, and foraging for food.[83][84] Louisiana slave records showed enslaved people ran away because of inadequate food and overwork. To survive, slaves stole food from their enslavers, killed cattle from nearby farms, and hunted and fished for food.[85]

Research from the National Park Service and professor George Estabrook said that enslaved people supplemented their diets "By boiling black-eyed peas, turnip greens, and pork fat in a single kettle and serving the mixture with grits made from home-ground corn, slaves cooked up meals that satisfied their dietary requirements, as well as their appetites." The black-eyed peas were a source of protein and the greens provided fiber and vitamins C and A.[86] Boiling greens in a kettle produced a vitamin-packed beverage called pot liquor that was consumed by the enslaved during the Antebellum era to maintain their health. White plantation owners ate the greens prepared by their slaves and left the green liquid (broth) for the slaves to drink not realizing the nutrients was in the broth. Pot liquor (also called potlikker) has Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin K, and iron. The enslaved and their descendants created healing remedies using pot liquors.[87][88][89][90] Slave gardens were important in the slave community, it supplemented slaves nutrient-deprived diet because their slaveholders did not provide enough food to feed them.[91][92][93] Slaveholders allowed their slaves to grow food in gardens because it saved their enslavers money, giving them an excuse not to buy food for their slaves. Some slaveholders provided the enslaved seeds to grow their own food. Slaves also made money by selling some of the food they grew to their enslavers.[94]

Chitterlings (also known as chitlins) are cleaned pig intestines; they are cooked in a pot and seasoned. This food has been associated with enslaved Black people in the American South; however, eating animal innards (intestines) is practiced in other cultures such as Asia, Europe, and West Africa. The Hausa people in West Africa eat chicken intestines. Enslaved Africans in the American South continued their traditions of cooking, seasoning, and eating animal innards. Enslaved people added extremely hot peppers for additional flavor and spice to their chitlins. Cooking chitlins was time consuming; field slaves slow cooked their pig intestines while they were working in the field. The parts of the pig that white plantation owners did not eat they gave to the enslaved which they used to season food and prepared one-pot meals, soups, and chitlin dishes.[95] Chitterlings are considered a delicacy in other cultures.[96] Due to the time it takes to clean pig intestines, chitterlings were preserved for special occasions and holidays. Some cooks season chitterlings with onions, celery, garlic, salt, pepper, and butter.[97] Booker T. Washington wrote that enslaved people ate chitlins during the Christmas season. Christmas in Virginia was a time when slaves hired to work on other plantations came home to visit their families at their enslaver's plantations. Enslaved families were supplied with food that consisted of chitlins, sausage, and side meats. After the American Civil War, cornbread, pigs' feet, hogs' ears, peas, and chitlins were prepared for Booker T. Washington's daughter, Portia Washington Pittman, 87th birthday.[98]

Foodways on the Underground Railroad

[edit]

Freedom seekers (runaway slaves) foraged, fished, and hunted for food on their journey to freedom on the Underground Railroad. With these ingredients, they prepared one-pot meals (stews), a West African cooking method. Enslaved and free Black people left food outside their front doors to provide nourishment to the freedom seekers. The meals created on the Underground Railroad became a part of the foodways of Black Americans called soul food. For example, Thomas Downing was born enslaved in 1791 on Chincoteague Island, on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. He learned how to harvest clams, oysters, and terrapin from the Chincoteague Bay, a lagoon of the Atlantic Ocean between Chincoteague and Assateague islands, and prepared meals from this seafood. Downing left Virginia during the War of 1812 and traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city that had Black Americans working in the culinary industry. There, he settled in the free Black community and found work catching oysters. Gaining his freedom in 1819, Downing, his wife, and sons moved to New York City, where the Hudson River provided work for New York's African American men working on the water harvesting oysters. By 1825 he had opened an oyster cellar, "Downing's Oyster House", on Broadway Street, in the city's business district. There he served raw, fried, and stewed oysters, oyster pie, fish with oyster sauce, and poached turkey stuffed with oysters. In the basement of his restaurant, Downing and his eldest son George hid people who were escaping slavery and seeking freedom. Downing became known as the "Oyster King of New York".[100][101][102][103]

Slave recipes

[edit]

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration paid American writers to gather stories from the last generations of African Americans born into slavery that are called slave narratives. Alongside the narratives are collections of recipes for sauces, desserts, and cooked meat and seafood dishes made by formerly enslaved African Americans. These records have been studied by John Blassingame, Michael Twitty, Jessica B. Harris, and other historians as they reveal the food culture and diets of enslaved people. The narratives show how enslaved people created new dishes that influenced Southern cuisine in the United States.[104] The foods enslaved people prepared in the kitchens for white plantation families influenced the diets and cooking methods of European Americans.[105]

Research from slave narratives showed enslaved people cooked sweet potatoes by roasting or frying them in lard. Sweet potatoes were mashed and sweetened with molasses. A traditional soul food dessert in Black families for Thanksgiving and Christmas is sweet potato pie.[105] Enslaved people also consumed pot liquor, the liquid left behind after boiling greens. George Key, who was born enslaved in Arkansas, said: "We had stew made out of pork and potatoes, and sometimes greens and pot liquor, and we had ash cake mostly, but biscuits about once a month."[106] Making pot liquor continued after emancipation. Jackie Torrence, an African American storyteller, remembers her grandmother making pot liquor from mustard greens, collard greens, pinto beans, peas, and white potatoes as gravy. Pot liquor was also used as a healing remedy to treat earache and ingrown toenails.[107]

A former slave named Wesley Jones from South Carolina gave a recipe to make a vinegar-based barbecue sauce using black and red peppers and vinegar. Wesley said slaves barbecued meats often, smoking and basting their meats with this homemade barbecue sauce; they would stay up all night slow cooking the meat. Other slave narratives described barbecuing as a preferred method of cooking because it added flavor and spice to food. Slaves barbecued their foods for special occasions and on their days off. Henry Bland,a former slave who lived in Georgia, said slaves had July 4 (Independence Day) off from work, allowing them to barbecue food, play ball games, wrestle, and play music.[108][109]

A former slave named Callie Elder from Georgia said her grandfather cooked catfish with lard, salt, and pepper, and rolled the catfish in cornmeal before baking. Former slave Clara Davis from Alabama cooked catfish using tomatoes and potatoes or prepared baked catfish with a tomato gravy and sweet potatoes. Slaves in the South fried catfish in lard or other fats and seasoned their food with salt acquired from evaporated sea water.[110] Enslaved people made use of fruits like apples and peaches that had been introduced to North America by European colonists. Some fruits, such as apples, were battered and deep fried in oil, fruit fritters were also fried, and peaches were stewed. Former slaves Mose King from Arkansas and Rose Williams from Texas described eating goat. Mary Minus Biddie was a former slave from Florida and said enslaved people cooked goat in a smokehouse. David Goodman Gullins was a former slave from Georgia and said they prepared barbecued goat. Goat is a traditional meat in West Africa and was commonly cooked and eaten in the American south by slaves.[111]

Enslaved people also barbecued squirrels. One recipe for barbecued squirrels that might have been similar to the way slaves cooked them was given in an 1879 cookbook: "Put them in the oven and let them cook until done. Lay them on a dish and set near the fire. Take out the bacon, sprinkle one spoonful of flour in the gravy and let it brown. Then pour in one teacup of water, one tablespoon of butter and some tomato or walnut catsup. Let it cool, and then pour it over the squirrel." Barbecuing and preparing barbecue sauce and hot sauce were done to season lower grades of meats.[112] Enslaved people living near rivers and the Atlantic Ocean caught crab and made stews with the crab meat in a pot with okra, sometimes adding a sauce. Cooking seafood with okra is a traditional cooking method from West Africa that slaves continued on Southern plantations.[113] Some of these recipes made by former slaves were published in African-American cookbooks. The earliest such cookbook was self-published in 1866 by Malinda Russell as a pamphlet titled, A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen.[114] A cookbook published in 1900 in the city of Charleston, South Carolina had recipes used by formerly enslaved Gullah people. Benne seeds from sesame, a plant native to West Africa, were eaten raw with sugar or milk. Enslaved people also made cakes, wafers, and brittles from them for white plantation families whom they called "buckra"[115] (a Gullah word for white people).[116][117]

Archeologist, historian, and former professional chef, Kelley Fanto Deetz, wrote a book, Bound to the Fire How Virginia's Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine, that said recipes prepared by enslaved cooks in Virginia contributed to some of the well-known fried and baked meat and vegetable dishes in American southern cuisine. The foods from West-Central Africa brought to the United States by way of the trans-Atlantic slave trade were used by enslaved cooks and combined with North American ingredients using West African, Native American, and European cooking methods to create meals that in the 17th century were necessary for survival that later influenced the foodways of southern Americans generally.[118]

Barbecue traditions

[edit]

Enslaved Africans in the American south contributed their own influence to the American barbecue tradition.[119] The first people to barbecue food in North America were Indigenous people/Native Americans. West and Central Africans had their own method of barbecuing food that they brought to the Americas and the West Indies. The Hausa people in West Africa had a term for barbecue, babbake. This term is used "...to describe a complex of words referring to grilling, toasting, building a large fire, singeing hair or feathers and cooking food over a long period of time over an extravagant fire".[109] The blending of Native American and African styles of barbecuing meat contributed to the creation of the current barbecuing culture in the US.[120] During slavery times, white plantation owners left the labor-intensive work of preparing and barbecuing food to their slaves.[121] Food historian Adrian Miller said the history of Black people and barbecue during slavery: "Blackness and barbecue were wedded in the public imagination because old-school barbecue was so labour intensive. Someone had to clear the area where the barbecue was held, chop and burn the wood for cooking, dig the pit, butcher, process, cook and season the animals, serve the food, entertain the guests and clean up afterward. Given the racial dynamics of the antebellum South, enslaved African Americans were forced to do that work. The media, in turn, took note that a barbecue, as a social event, was a black experience from beginning to end."[122][123][124] On Fourth of July celebrations, the enslaved prepared barbecued food for white politicians and their enslavers.[109]

Enslaved people brought their own influences on the creation of barbecue sauce.[125] Hot and sweet sauces are used in West and Central African cuisine to add flavor, heat, and moisture to food.[121] In 1748, Peter Kalm, a Swedish-Finnish botanist, noted enslaved Africans in Philadelphia cultivated guinea peppers and the pods were pounded and "mixed with salt preserved in a bottle" to make sauces poured over fish and meats.[126] Frederick Douglass Opie, writing in his book Hog and Hominy, describes the origins of soul food in Africa: "African women cooked most meats over an open pit and ate them with a sauce similar to what we now call a barbecue sauce, made from lime or lemon juice and hot peppers."[127] "Slaves made up a large percentage of the Texas population by 1860. During this time they brought with them the idea of cooking over an open fire and dousing meats with a sauce, that sounds an awful lot like the barbecue sauce we know today."[128] After the American Civil War, a Black pitmaster named Arthur Watts, brought his family's barbecue sauce recipe and barbecuing methods to Kewanee, Illinois and became a well-known pitmaster.[129] In African-American communities, barbecuing food became a preferred method of cooking during Emancipation Day celebrations.[109]

Emancipation

[edit]

On January 1, 1863, Gullah people in the Sea Islands of South Carolina celebrated their freedom on New Year's Day at Camp Saxton in Beaufort with food and barbecues. Black people in the barrier islands of South Carolina became free early during the American Civil War after the Battle of Port Royal on November 7, 1861, when many of the plantation owners and white residents fled the area after the arrival of the Union Navy and Army. As a result, over 10,000 African Americans became free on that day.[130] However, their freedom was not official in government writing until the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year's Day in 1863. Thousands of newly freed people celebrated their freedom with food, song, and dance.[131] Charlotte Forten, the first black teacher at the Penn School on St. Helena Island in Beaufort, attended the Emancipation Day celebration at Camp Saxton and recorded in her journal they ate roasted oxen and barbecue.[132][133][134] Susie King Taylor, a Geechee woman born enslaved in Liberty County, Georgia, wrote in her memoir that she had also attended the Emancipation Day celebration at Camp Saxton: "It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it, and as a fitting close and crowning event of this occasion we had a grand barbecue".[135] Other Emancipation Day celebrations were celebrated with a barbecue feast, a tradition that originated in the slave community.[136][137]

After the American Civil War, 4 million African Americans were freed from slavery. They celebrated their newly won freedom with barbecues and Emancipation Day celebrations and prepared soul food meals. Two months after the Civil War ended in April 1865, slaveholders in Galveston, Texas refused to tell their slaves the Civil War had ended and they were free. On June 19, 1865, United States Brigadier General Gordon Granger and his troops arrived in Galveston and issued General order No. 3. This order enforced the Emancipation Proclamation which declared enslaved people in Texas were now free.[138] To celebrate their freedom, African Americans in Galveston, and other Black communities in the United States, gathered at public parks and prepared red foods that represent the color of freedom. These celebrations are called Juneteenth, which became a national holiday under the Biden Administration in the year 2021.[139]

According to food historian Michael Twitty, the reason African Americans eat red food on Juneteenth is that it reminds them of the blood of their ancestors that was shed during slavery, and the cultural colors of the Yoruba and Bakongo people, who were enslaved in the Southern United States and brought to North America under the slave trade. Among the Yoruba and Bakongo people, the color red represents power, sacrifice, and transformation.[140][141] The red foods eaten at Juneteenth are, watermelon, red lemonade, and red velvet cake.[142] In addition to red foods, BBQ, fried foods, and other cooked meals are prepared to celebrate the day of freedom.[143]

After emancipation, many Black Americans in the South became sharecroppers and cooked what was available in their region. This created regional styles of cooking with similar dishes passed down orally in Black families.[144][145][146] Due to slave laws, it was illegal in many states for slaves to learn to read or write. Soul food recipes and cooking techniques were passed down orally until after emancipation.[147]

The first soul food cookbook is attributed to Abby Fisher, entitled What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking and published in 1881. Good Things to Eat was published in 1911; the author, Rufus Estes, was a former slave who worked for the Pullman railway car service. Many other cookbooks were written by Black Americans during that time, but as they were not widely distributed, most are now lost.[148]

Global spread of African-American cuisine

[edit]

The global spread of soul food came during World War I and World War II. Thousands of Black Americans enlisted in the army as soldiers and nurses. Some Black soldiers chose to stay overseas than return to the United States where Jim Crow laws, racism, and lynchings were widespread. African American service men and women opened soul food restaurants in Europe, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, and Japan and introduced African-American cuisine to people in foreign countries. In the 1920s through the 1940s, African-American culture was popular in France. French people enjoyed jazz, African-American dance, and cuisine. Food historian Adrian Miller said the global spread of soul food: "The global spread of soul food really took off after the end of World War II. After the war, recently discharged black military veterans in the European theater stayed overseas to open and operate restaurants. At first, they cooked mainly for African Americans who were active-duty military and serving at nearby bases. In some of the countries where the United States had a military presence, like France, Germany, Japan, Vietnam, and Thailand, it was easy for these entrepreneurs to find the cheap ingredients they needed for their recipes, because the locals ate similar foods: chicken, fish, greens, okra, pork, sweet potatoes."[149]

Mid-20th century to present day

[edit]

The introduction of soul food to cities such as Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Harlem came during the Great Migration as African Americans moved to the North looking for work. Sylvia Woods was born in Hemingway, South Carolina in 1926. When Woods was a teenager she moved to Harlem and worked in a Brooklyn factory. In 1954, Woods changed jobs and started working at Johnson's Luncheonette located in central Harlem. Seven years later, Woods and her husband purchased the luncheonette and opened it as a soul food restaurant in 1962, calling it Sylvia's Restaurant.[152][153] Sylvia Woods became known as the "queen of soul food."[154]

Food historian Adrian Miller studied soul food's development in Maryland and in Northern American states. Soul food in Maryland's Black communities added local flavors from seafood from the Chesapeake Bay. People in Maryland fried chicken in shallow fat in a frying pan, covering it with a lid, thus frying and steaming the chicken, which was served with waffles.[155][156] Chicken and waffles became a common soul food item to eat in Black communities in Maryland and in Harlem, New York. During the blues and jazz era, musicians and singers performed and practiced late into the night and stopped at black-owned restaurants for food where cooks prepared fried chicken and waffles for their customers.[157][158] Nightclubs in Black communities in the United States during the Jim Crow era were called the Chitlin' Circuit, named after the dish that was usually associated with Black southerners and soul food.[159][160] The Chitlin' Circuit was given its name by entertainers because it included black-owned night clubs that served chitlins (chitterlings) and soul food.[161]

During the civil rights movement, soul food restaurants were places where civil rights leaders and activists met to discuss and strategize civil rights protests and ideas for implementing social and political change.[162] Paschal's Restaurant in Atlanta, like Georgia Gilmore's eatery in Montgomery, had an imporatnt part in the civil rights movement. Upon returning to Atlanta from Montgomery, Martin Luther King got permission "to bring his team members and guests to Paschal's to eat, meet, rest, plan, and strategize."[163] The Atlanta History Center said: "Throughout the civil rights movement in Atlanta, soul food restaurants were hubs of change where civil rights leaders could convene, converse, and strategize, and in times of terror and violence, these places were retreats where leaders could plan their next tactical moves, giving many of these spots a legacy beyond good cooking". Soul food restaurants in Atlanta, Georgia served as the primary meeting places for numerous civil rights leaders and supporters of the movement. Many politicians and civil rights leaders gathered to discuss plans about the movement at Paschal's Restaurant on West Hunter Street. In the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights icons such as Andrew Young, John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Jesse Jackson frequented the restaurant, staying late into the night talking about civil rights strategies and politics. Several soul food restaurants were located on West Hunter Street because Jim Crow laws restricted where African Americans were allowed to operate their businesses.[164][165]

In 1963, a few days before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington D.C., where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his I Have a Dream Speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King ate at a soul food restaurant called the Florida Avenue Grill. During the years of the civil rights movement, other civil rights leaders and activists met at the restaurant, planning and strategizing for the movement. Before King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, he ate at the Four Way restaurant and had fried catfish and lemon icebox pie. Throughout his civil rights career, King frequented several soul food restaurants where he ate and met with other local and national civil rights leaders.[166] After King's assassination, riots broke out in Washington D.C., and the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Stokely Carmichael, asked the owner of Ben's Chili Bowl restaurant to remain open to provide food for police officers, student activists, and firefighters as they worked together to stop the riot. Authors Hoekstra and Khan said in their book, The People's Place: Soul Food Restaurants and Reminiscences from the Civil Rights Era to Today, that soul food restaurants served as places to bring communities and families together in times of trouble during the Jim Crow era and helped in the fight against segregation laws by allowing white and Black people to eat together.[167]

In Montgomery, Alabama, civil rights protestors convened and organized for the movement at soul food restaurants because they provided a safe haven and a place to eat and relax. Martha's Place and Chris' Hotdogs were visited by protestors. During this period of activism, Jereline and Larry James Bethune, the owners of the restaurant Brenda's BBQ, also in Montgomery, taught African Americans how to register to vote and how to read a ballot when Jim Crow laws and literacy tests prevented Black people from voting. Civil rights activists frequented the restaurant for moral and financial support. The owners also helped to print out fliers for the movement and allowed protestors to have secret meetings in the back of the restaurant.[168]

Atlanta's oldest black-owned restaurant, the Evelyn Jones Cafe, was founded in 1936 by Evelyn Jones and her sister. In the mid-1940s, Evelyn and her husband, Luther Frazier, enlarged the restaurant and renamed it Frazier's Cafe Society. It is located at 880 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive (then known as West Hunter Street). The Jones family challenged Jim Crow laws when they allowed whites and blacks to eat together. It was the first interracial restaurant on West Hunter Street. The cafe also served as a location for civil rights leaders to meet. The foods the restaurant served were Virginia baked ham, pork chop dinner, jumbo shrimp, roast beef, and other classic Southern dishes.[169][170] Club from Nowhere was a black-owned soul food restaurant that opened in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, operated by civil rights activist Georgia Gilmore. Gilmore's fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, stuffed pork chops, stuffed peppers, and coleslaw were popular among her black and white customers. These were dishes she learned how to make from the women in her family. Gilmore's restaurant provided food for civil rights leaders during the Montgomery bus boycott, and her soul food was a favorite among Martin Luther King Jr.[171] Several soul food restaurants served black and white people before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made segregated facilities illegal.[172][173]

During the Jim Crow era in the 20th century, it was not safe for Black Americans to travel on the road as they faced possible violence from white supremacists. Black people needed to know what places were safe to stop for food, gas, and motels. In 1936, an African American postal worker from Harlem, New York, named Victor Hugo Green created The Green Book for Black people to travel safely in the Southern United States, where Jim Crow laws were widespread. Several soul food restaurants were listed in the book because they were safe havens for African Americans to eat. One restaurant listed in the Green Book was Swett's, which opened in 1954.[174][175]

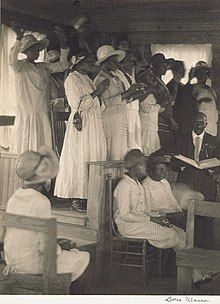

The Black Church (African-American churches) played a key role in Black communities as they provided food and a place of worship. Researchers from PBS said: "Religion played a key role in the proliferation of soul food, as well as the diversification of the cuisine. Black churches, crucial during slavery and in the Civil Rights movement, were also crucial as gathering places, where Black communities could eat and rejoice over plates of chicken and dumplings, black-eyed peas and rice, red drinks, and the classic Black American church dish, fried catfish and spaghetti".[176] Chris Carter is an African American pastor and professor of history who published a book about the Black Church and soul food in 2021 titled, The Spirit of Soul Food: Race, Faith, and Food Justice. According to Carter, soul food in the African-American community is food that fights injustices centered around the lack of access to food, as some Black Americans live in poverty and Black churches on Sundays and during the week prepare meals to feed their community.[177]

Since the mid-20th century, many cookbooks highlighting soul food and African-American foodways have been compiled and published. One notable soul food chef is celebrated traditional Southern chef and author Edna Lewis,[178] who released a series of books between 1972 and 2003, including A Taste of Country Cooking in which she weaves stories of her childhood in Freetown, Virginia into her recipes for "real Southern food".[179]

Another early and influential soul food cookbook is Vertamae Grosvenor's Vibration Cooking, or the Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl, originally published in 1970, focused on South Carolina Lowcountry/Geechee/Gullah cooking. Its focus on spontaneity in the kitchen—cooking by "vibration" rather than precisely measuring ingredients, as well as "making do" with ingredients on hand—captured the essence of traditional African-American cooking techniques. The simple, healthful, basic ingredients of lowcountry cuisine, like shrimp, oysters, crab, fresh produce, rice, and sweet potatoes, made it a bestseller.[180]

Usher boards and Women's Day committees of various religious congregations large and small, and even public service and social welfare organizations such as the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) have produced cookbooks to fund their operations and charitable enterprises.[181][182] The NCNW produced its first cookbook, The Historical Cookbook of the American Negro, in 1958, and revived the practice in 1993, producing a popular series of cookbooks featuring recipes by famous Black Americans, among them: The Black Family Reunion Cookbook (1991), Celebrating Our Mothers' Kitchens: Treasured Memories and Tested Recipes (1994), and Mother Africa's Table: A Chronicle of Celebration (1998). The NCNW also recently reissued The Historical Cookbook.[183][184][185]

The Special Collections at the University of Alabama has the largest collection of over 450 African-American cookbooks. Kate Matheney, a librarian at the University of Alabama, studied the history of African-American cookbooks and found that several Black cookbooks were authored by white women. As they were the primary cooks in plantation houses, enslaved Africans in Alabama influenced the foodways of whites there. During the Jim Crow era, African American women worked in the homes of white families as domestics and prepared their meals. Some white women authored Black cookbooks using stereotypical images of black women as Mammies on the cover of cookbooks to better market the recipes they learned from black cooks to audiences. African Americans authored their cookbooks using non-stereotypical images and added recipes they learned from their family.[171]

In 2011, culinary historian Jessica B. Harris published a book titled, High on the Hog that describes the origins and development of African-American dishes and their roots in Sub-Saharan Africa. Enslaved and free African Americans incorporated indigenous foods from North America such as plants, fruits, and animals but Africanized the foods by preparing and flavoring their dishes similarly to West and Central Africans.[186] Harris' book later became a docuseries in 2021 on Netflix called High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America.[187]

In 2018 African American author and culinary historian Michael Twitty published The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South about the history, development, and evolution of soul food in Black communities in the Southern United States.[191][192]

Gullah Geechee chef Emily Meggett was born on Edisto Island, South Carolina in 1922. Meggett learned how to farm and cook from her family and published a book about Gullah cuisine in 2022 titled, Gullah Geechee Home Cooking: Recipes from the Matriarch of Edisto Island.[193][194]

In 2024, Lakisha Harris became the first Black woman in the United States to present a presentation on soul food at the American Culinary Federation (ACF) National Convention titled, Culinary Freedom of the Soul.[195]

Gullah Geechee chef Benjamin Dennis IV, born in Charleston, South Carolina, teaches about Gullah and African-American cuisine's origins in West African cuisine and its influence on American foodways.[196][197]

Professional chef Mashama Bailey cooks a fusion of foods derived from the African diaspora with Old World and New World cuisine (of the Southern United States) at The Grey restaurant in Savannah, Georgia. Bailey learned how to cook soul food from her mother and attended the Institute of Culinary Education; she then traveled to Burgundy, France, where she trained under French chefs. Bailey blends Gullah Geechee cuisine with other cuisines of the African diaspora and continues to educate the public about African-American food culture.[198][199]

Ashleigh Shanti is an Affrilachian chef who owns the restaurant Good Hot Fish in Asheville, North Carolina. She opened a restaurant with a focus on Black Appalachian cuisine and culture. She said "A big part of why I fell in love with the restaurant industry was watching the women in my family and the power they had serving simple, humble food. I thought it was incredible: how their food could transform someone's mood, making them happy, making them cry."[200][201]

African American chef Carla Hall, author of the cookbook Carla Hall's Soul Food: Everyday and Celebration, is a television personality and the culinary ambassador to the National Museum of African American History and Culture Sweet Home Cafe in Washington, D.C. Hall has Yoruba ancestors from Nigeria, West Africa, and Bubi ancestors from Equatorial Guinea in Central Africa.[202][203]

African-American cuisine in Mexico

[edit]Tiara Darnell, an African American woman born in Mitchellville, Maryland, moved to Mexico and opened a soul food restaurant in Mexico City called Blaxicocina. Darnell prepares traditional soul food dishes using Mexican ingredients. The dishes she makes in her restaurant are all family recipes passed down from family members who live in Prince George's County, Maryland and Washington, D.C. The soul food cuisine Darnell makes adds Mexican flavors and ingredients blending African-American cuisine with Mexican cuisine.[204]

African influence

[edit]

Scholars have found substantial African influence in soul food recipes, especially from the West and Central regions of Africa. This influence can be seen in the heat level of many soul food dishes, as well as many ingredients used to prepare them.[205][206] Peppers used to add spice to food include malagueta pepper, as well as variants native to the Western Hemisphere such as red (cayenne) peppers.[44] Several foods essential to Southern cuisine and soul food were domesticated or consumed in the African savannah and the tropical regions of West and Central Africa. The foods brought from Africa to North America include gherkin, cantaloupe, eggplant, kola nuts, watermelon, pigeon peas, black-eyed peas, okra, sorghum, and guinea pepper.[205][40][207][208]

A species of rice, Oryza glaberrima was domesticated in Africa, and many people brought to the Americas preserved rice cooking techniques. Rice was a cash crop in the South Carolina Lowcountry, and during the slave trade, Europeans selected coastal inhabitants of West Africa who had knowledge of rice cultivation.[209][210] Rice is a staple side dish in the Lowcountry region and in Louisiana. It is a main ingredient in dishes such as jambalaya and red beans and rice, popular in Southern Louisiana. Recipes for rice and beans developed in West Africa were brought to the South Carolina Lowcountry by enslaved Africans and continue to be prepared by their descendants, the Gullah people. A Gullah dish of rice, black-eyed peas, onions, and bacon is Hoppin' John.[211] Food historian Jessica B. Harris traces this dish to a Senegalese food called Chiebou niebe, made with rice and beef. Enslaved Black Americans in the United States thus created new dishes with origins in West Africa but using North American ingredients.[212] A Gullah New Year tradition is eating Hoppin' John to bring in good luck. Customarily eaten on January 1 throughout the Lowcountry region, it is often paired with cornbread and collard greens, which are also said to bring prosperity.[213]

Charleston red rice is made with rice and tomato paste. This dish originated from jollof rice in West Africa, which is made with a tomato product giving the rice its red color.[214] In the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia, enslaved Gullah Geechee people's main source of food was rice paired with meats and shellfish. These rice cooking techniques, influenced by rice dishes made in West Africa, are practiced today in Gullah communities.[215][216]

There are many documented parallels between the foodways of West Africans and soul food recipes.[217] The consumption of sweet potatoes in the United States echoes the consumption of yams in West Africa. The presence of cornbread on African-American tables is analogous to West African use of fufu to soak up sauces and stews.[217]

Harris starred in the 2021 docuseries High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America and traveled to Benin, West Africa, where she saw women making a leafy sauce called feuille, prepared similarly to how African Americans cook collard greens.[218]

West Africans also cooked meat over open pits and brought their methods of barbecuing and making barbecue sauce to the Americas. The Hausa word for barbecue is babbake.[109] Indigenous peoples in North America also barbecued their meats. African Americans use African and Native American techniques of barbecue.[120][44][219]

It was not uncommon to see food served out of an empty gourd. Many techniques to change the overall flavor of staple food items such as nuts, seeds, and rice contributed to added dimensions of evolving flavors. These techniques included roasting, frying with palm oil, baking in ashes, and steaming in leaves such as banana leaf.[220]

Native American influence

[edit]

Southeastern Native American culture is an important element of Southern cuisine. From their cultures came one of the main staples of the Southern diet: corn (maize), either ground into meal or limed with an alkaline salt to make hominy, in a Native American process known as nixtamalization.[221] Corn was used to make all kinds of dishes, from the familiar cornbread and grits to liquors such as moonshine and whiskey (which are still important to the Southern economy[222]). Black Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama combined molasses and leftover cooked grease, a combination they called "sap", to pour over their cornbread and "hoe cakes".[223] An additional Native American influence in soul food is the use of maple syrup. Indigenous people used maple syrup to sweeten and add flavor to dishes; this influenced the foodways of African Americans as they used maple syrup to sweeten their dishes and poured syrup over pancakes and other breakfast foods.[224]

The foods of Black Seminoles in Florida and Oklahoma are influenced by Gullah rice and bean dishes and Seminole foodways. Black Seminoles cooked rice, "sometimes applying a sauce of okra or spinach leaves".[225][226] Historian Ray Von Robertson conducted oral interviews with sixteen Black Seminoles from 2006 and 2007 and found that Seminole cultural influences were incorporated into their daily lives in practices such as foodways and herbal medicine. Black Seminoles cooked and ate fry bread, sofkee, and grape dumplings.[227]

Many fruits are available in this region: blackberries, muscadines, raspberries, and many other wild berries were part of Southern Native Americans' diets as well.

To a far greater degree than anyone realizes, several of the most important food dishes that the Native Americans of the southeastern U.S.A live on today is the "soul food" eaten by both Black and White Southerners. Hominy, for example, is still eaten: Sofkee lives on as grits; cornbread [is] used by Southern cooks; Indian fritters -- variously known as "hoe cake" or "Johnny cake"; Indian boiled cornbread is present in Southern cuisine as "corn meal dumplings" and "hush puppies"; Southerners cook their beans and field peas by boiling them, as did the Native tribes; and, like the Native Americans, Southerners cured their meats and smoked it over hickory coals...

— Charles Hudson, The Southeastern Indians[228]

African, European, and Native Americans of the American South supplemented their diets with meats derived from the hunting of native game. What meats people ate depended on seasonal availability and geographical region. Common game included opossums, rabbits, and squirrels.[229]

Sauces and seasoning

[edit]

Since the mid-20th century, Black Americans have seasoned cooked meats and vegetables with Lawry's Seasoned Salt. Because Lawry's is economical and offers multiple herbs and spices in one product, Black Americans use it in most of their dishes except sweet dishes.[230][231][232] For extra flavor and spice, hot sauce is sprinkled over fried chicken and fish, collard greens, and other cooked foods. West Africans made variations of hot spicy sauces using hot peppers indigenous to the region. After their enslavement and transportation to the southern United States, they continued to make their own versions of hot sauces using spices and peppers from North America. By the mid-20th century, Black Americans were turning to store-bought hot sauces to add flavor and spice to their food.[233][234] During slavery times, enslaved people had flavored their vegetables with bacon grease or other parts of the pig. This tradition continues today with Black families using pig feet, bacon grease, or turkey necks to flavor collard and turnip greens.[235]

Culinary historian Michael Twitty, thinks enslaved African Americans likely influenced the creation of Old Bay Seasoning, saying, "It's not that African Americans necessarily invented it, but without us, the story is impossible." In his travels to West Africa, Twitty observed how West Africans always add peppers, salt, and a hot condiment to their seafood dishes. Twitty believes enslaved West Africans were probably the first to put "kitchen pepper" on shellfish. In colonial America, kitchen pepper was a common kitchen spice blend that often included nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, allspice, ginger, black pepper, and mace. He notes that "there's always a peppery, salty kind of thing that you eat crustaceans with. It's always with a hot condiment—it's never just plain." Twitty believes that hundreds of years of cooking shellfish with kitchen pepper developed into the crab spice blends common in the Chesapeake Bay area when Gustav Brunn came to Baltimore.

The founder of the Old Bay Seasoning company, Gustuv Brunn was a German Jewish immigrant who came to the United States in the 1930s with his family to flee Adolf Hitler's ascent to power. After Brunn arrived in Baltimore, he created his own seafood seasoning blend influenced by local seasoning recipes and called it Delicious Brand Shrimp and Crab Seasoning, but it was not popular with the locals. Brunn changed the name to Old Bay and sold a few pounds of Old Bay to a nearby seafood wholesaler. Word spread and over time it became a popular seasoning.[236][237] Seafood dishes in soul food cuisine today will have Old Bay as the primary seasoning combined with other herbs and sauces to add robust flavor.

Cultural relevance

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| American cuisine |

|---|

|

Soul food originated in the southern region of the US and is consumed by African-Americans across the nation. Traditional soul food cooking is seen as one of the ways enslaved Africans passed their traditions to their descendants once they were brought to the US. It is a cultural creation stemming from slavery and Native American and European influences.[217][44]

Soul food recipes are popular in the South due to the accessibility and affordability of the ingredients.[217][43] Scholars have said that while white Americans provided the material supplies for soul food dishes, the cooking techniques found in many of the dishes have been visibly influenced by the enslaved Africans themselves.[44]

The bountiful vegetables found in Africa were substituted in dishes down south with new leafy greens consisting of dandelion, turnip, and beet greens. Pork, more specifically hog, was introduced into several dishes in the form of cracklins from the skin, pigs' feet, chitterlings, and lard used to increase the fat intake into vegetable dishes. Spices such as thyme, and bay leaf blended with onion and garlic gave dishes their own characteristics.[220]

Red drinks are common at African American social functions. Restaurants with a mostly black clientele typically serve at least one red drink. Red drinks are important in soul food culture because they represent social connections between friends and family, and a link with the African diaspora.[238] Newbell Puckett, a southern sociologist who documented African American folk beliefs in his 1926 study, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro,[239] said that there was cultural and historical continuity between African American culture and West African societies where red had been an important ritual and royal color for hundreds of years. There were two notable red drinks in West Africa, kola tea and hibiscus tea, by the time the Atlantic slave trade began. Kola tea was made from the nuts of West African trees, especially Cola nitida. Tea made from the dried red flowers of the hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa), a plant related to okra, is used to make a tea called bissap, from the French jus de bissap. It is popular in Senegal and Gambia. Bissap was called sorrel tea or red sorrel in the Americas.[238]

Figures such as LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Elijah Muhammad, and Dick Gregory played notable roles in shaping the conversation around soul food.[240][217] Muhammad and Gregory opposed soul food because they felt it was unhealthy and was slowly killing African-Americans.[15] They saw soul food as a remnant of oppression and felt it should be left behind. Many African-Americans were offended by the Nation of Islam's rejection of pork as it is a staple ingredient used to flavor many dishes.[217]

Stokely Carmichael also spoke out against soul food, claiming that it was not true African food due to its colonial and European influence.[217] Many voices in the Black Power Movement saw soul food as something African-Americans should take pride in and used it to distinguish African-Americans from white Americans.[16] Proponents of soul food embraced the concept and used it as a counterclaim to the argument that African-Americans had no culture or cuisine.[44][217]

Soul food spread throughout the United States when African-Americans from the South moved to major cities across the country such as Chicago and New York City during the Great Migration. They brought with them the foods and traditions of the Southern United States, where they had been enslaved.[6] Later, the magazine Ebony Jr! was important in transmitting the cultural relevance of soul food dishes to middle-class African-American children who typically ate a more standard American diet.[241] Today Soul food is frequently found at religious rituals and social events such as funerals, fellowship, Thanksgiving, and Christmas in the black community.[217][178][205]

Soul food is culturally similar to Romani cuisine in Europe.[242]

Health concerns

[edit]Soul food prepared traditionally and consumed in large amounts can be detrimental to one's health. Opponents of eating soul food have been vocal about health concerns surrounding the culinary traditions since the name was coined in the mid-20th century.[243][244]

Soul food has been criticized for its high starch, fat, sodium, cholesterol, and caloric content, as well as the inexpensive and often low-quality nature of the ingredients such as salted pork and cornmeal. In light of this, soul food has been implicated by some in the disproportionately high rates of high blood pressure (hypertension), type 2 diabetes, clogged arteries (atherosclerosis), stroke, and heart attack suffered by African-Americans.[245][246] Figures who led discussions surrounding the negative impacts of soul food include Dr. Alvenia Fulton, Dick Gregory, and Elijah Muhammad.[240][217]

On the other hand, critics and traditionalists have argued that attempts to make soul food healthier also make it less tasty, as well as less culturally/ethnically authentic.[247][248] There is also often a foundational difference in how health is perceived; perceptions of healthiness by consumers of soul food may differ from normal understandings in American culture.[249]

The nutritional value of most processed foods, and not just those implicated in a traditional perception of soul food, has degraded as the agricultural system in the United States became industrialized, fueled by federal subsidies.[250] This urges a consideration of how concepts of racial authenticity evolve alongside changes in the structures that make some foods more available and accessible than others.[251][252]

An important aspect of the preparation of soul food was the reuse of cooking lard. Because many cooks could not afford to buy new shortening to replace what they used, they would pour the liquefied cooking grease into a container. After cooling completely, the grease re-solidified and could be used again the next time the cook required lard.[253] With changing fashions and perceptions of healthy eating, some cooks may use preparation methods that differ from those of cooks who came before them: using liquid oil like vegetable oil or canola oil for frying and cooking, and using smoked turkey instead of pork, for example. Changes in hog farming techniques have also resulted in drastically leaner pork, in the late 20th and 21st centuries. Some cooks have even adapted recipes to include vegetarian alternatives to traditional ingredients, including tofu and soy-based analogues. Several Black chefs have opened vegan soul food restaurants to cook healthier foods rooted in African American culture.[254][255] Others, such as Jenne Claiborne, author of the Sweet Potato Soul Cookbook, have started a YouTube channel and show people how to prepare healthier soul food.[256]

Several of the ingredients included in soul food recipes have pronounced health benefits. Collard and other greens are rich sources of several vitamins (including vitamin A, B6, folic acid or vitamin B9, vitamin K, and C), minerals (manganese, iron, and calcium), fiber, and small amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. They also contain a number of phytonutrients, which are thought to play a role in the prevention of ovarian and breast cancers.[257][dubious – discuss]

The traditional preparation of soul food vegetables often consists of high temperatures or slow cooking methods, which can lead the water-soluble vitamins (e.g., Vitamin C and the B complex vitamins) to be destroyed or leached out into the water in which the greens are cooked. This water is often consumed and is known as pot liquor.[178] Because it contains micronutrients from the greens cooked in it, pot liquor contributes to the nutritional value of a meal when consumed.[258] Peas and legumes are inexpensive sources of protein, and they also contain important vitamins, minerals, and fiber.[259]

Dishes and ingredients

[edit]See also

[edit]- African cuisine

- Black veganism

- Cajun cuisine

- Caribbean cuisine

- Cuisine of Antebellum America

- Cuisine of Atlanta

- Cuisine of New Orleans

- Cuisine of the Southern United States

- Fried chicken stereotype

- High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America

- Indigenous cuisine of the Americas

- List of foods of the Southern United States

- Louisiana Creole cuisine

- Native American cuisine

- Slave health on plantations in the United States#Slave diet

- Soul Food Junkies, a documentary

- West African cuisine

References

[edit]- ^ ""Soul Food" a brief history". African American Registry. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- ^ Moskin, Julia (2018-08-07). "Is It Southern Food, or Soul Food?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ a b "An Illustrated History of Soul Food". First We Feast. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Ferguson, Sheila (1993). Soul Food Classic Cuisine from the Deep South. Grove Press. pp. 57–60. ISBN 9781493013418.

- ^ McKendrick, P.J. (15 December 2017). "The Diversity of Soul Food - Global Foodways". Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ a b Wallach, Jennifer Jensen (2018). Every Nation Has Its Dish: Black Bodies and Black Food in Twentieth-Century America. UNC Press Books. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-1-4696-4522-3.

- ^ "Soul Food". Macaulay.cuny.edu. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Hoekstra, Dave; Chaka, Khan; Paul, Natkin (2015). The People's Place Soul Food Restaurants and Reminiscences from the Civil Rights Era to Today. Chicago Review Press. pp. 1958, 1962. ISBN 9781613730621.

- ^ a b Brownell, Kelly. "Adrian Miller on the History of Soul Food". World Food Policy Center. Duke Sanford. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Faries, Dave (2022). "What is the difference between soul food and Southern cooking?". Monterey County Now. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Heath, Mary (2017). "Southern Food Vs. Soul Food: What's The Difference?". Grady Newsource. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Fried Dough History". Archived from the original on October 12, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Thomas. "Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or the Story of My Life in Three Continents". Documenting the American South. UNC Chapel Hill University. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Witt, Doris (1999). Black Hunger: Food and the Politics of U.S. Identity. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-19-535498-0.

- ^ a b Rouse, Carolyn Moxley (2004). Engaged Surrender: African American Women and Islam. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, London, England: University of California Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-520-23794-0.

- ^ a b Witt, Doris (1999). Black Hunger: Food and the Politics of U.S. Identity. Oxford University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-19-535498-0.

- ^ Poe, Tracy N. (1999). "The Origins of Soul Food in Black Urban Identity: Chicago, 1915-1947". American Studies International. XXXVII No. 1 (February): 4–17.

- ^ Muhammad, Karyn (2024). "How soul food became a staple in the Black community". Alabama State University. The Hornet Tribune Online. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Notable African American chefs". Begley Library. Schenectady County Community College. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Henderson, Laretta (2007). "'Ebony Jr!' and 'Soul Food': The Construction of Middle-Class African American Identity through the Use of Traditional Southern Foodways". Melus Food in Multi-Ethnic Literatures. 32 (4): 81–82. JSTOR 30029833. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Kelly, Leslie. "Celebrating National Soul Food Month With Celebrity Chef Carla". www.forbes.com. Forbes Newsletters. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Townsend, Bob (2019). "Recipes that celebrate the culinary history of the African diaspora". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b Holloway, Joseph. "African Crops and Slave Cuisine". Slave Rebellion Info. Slave Rebellion Website. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "Diet and Nutrition". Santa Clara University Digital Exhibits. Santa Clara University. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b Davis, Donald (2006). Southern United States: An Environmental History. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 9781851097852.

- ^ Horgan, John. "Columbian Exchange". www.worldhistory.org. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ J. Wallach, Jennifer (2019). Getting What We Need Ourselves:How Food Has Shaped African American Life. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 13–15. ISBN 9781538125250.

- ^ Addison, Sydney; Bryan, Kailey; Carter, Taylor; Del Tufo, J.T.; Diallo, Aissatou; Kinzey, Alyson. African Americans and Southern Food. Mercer University (Report). hdl:10898/1521. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Poche, Dixie (2023). Cajun Mardi Gras A History of Chasing Chickens and Making Gumbo. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781439676790.

- ^ Penniman, Leah (2018). Farming While Black Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 9781603587617.

- ^ Carney, Judith (2013). "Seeds of Memory: Botanical Legacies of the African Diaspora" (PDF). African Ethnobotany in the Americas: 15, 20. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Twitty, Michael. "Foodways of the Transatlantic Slave Trade". www.masterclass.com. Master Class. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Twitty, Michael. "How rice shaped the American South". www.bbc.com. BBC. Retrieved 6 June 2024.