Abbey of Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains

| Abbey of Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic church |

| District | Lyon |

| Province | Rhône |

| Region | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 17th century by François de Royers de La Valfenière |

The Abbey of Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains in Lyon, also known as the Abbey of the Dames de Saint-Pierre or simply Palais Saint-Pierre, is an ancient Catholic religious edifice that housed Benedictine nuns from the 10th century onwards, and was rebuilt in the 17th century. Closed during the French Revolution, the former abbey is now home to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

History

[edit]The origins of Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains abbey

[edit]The exact date of the abbey's foundation is unknown, and research is complicated by the unreliability of the earliest documents. In the 6th century, the "testament" of the bishop of Lyon Ennemond relates that Aldebert, governor of Lugdunum under the reign of Septimius Severus, having converted to Christianity, endowed the "monastery of the Ladies of Saint-Pierre" with land in 208.[1] According to Ennemond, the monastery was already governed by abbesses in the 5th and 6th centuries. Historian Alfred Coville has established that Ennemond's will, which is peppered with anachronistic formulations, was a forgery fabricated in the middle of the Middle Ages, probably to justify the abbey's property rights.[2] After a critical study of ancient sources, Pierre Picot situates the first construction during the Merovingian period under Bishop Sacerdos of Lyon, and attributes the constitution of the monastic community to Bishop Ennemond, in the 7th century,[3] a dating nevertheless judged hypothetical by Joachim Wollasch.[4]

There are no contemporary documents to indicate the precise date on which the Benedictine rule was adopted by the nuns. Berger de Moydieu, an 18th-century author, asserts that it came into force under the abbatiate of Ennemond's sister Lucie, between 665 and 675.[5][6] Pierre Picot prefers to place this adoption later, at the time of Benedict of Aniane (d. 821), an active promoter of the rule.[7] Joachim Wollasch agrees, drawing a parallel with the case of Remiremont Abbey, whose nuns adopted the same rule under Louis the Pious.[4]

During Charlemagne's reign, Archbishop Leidrad of Lyon, whose letters mentioning the abbey have been preserved, had it completely rebuilt. From this time onwards, the abbey, known as Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains, was the richest religious establishment in the city. It also became increasingly independent from the rest of Lyon's clergy, reporting directly to the papacy.[8]

The abbey from the 11th to the 18th century

[edit]

In the Middle Ages, the abbey was referred to in official texts as "Monasterium sancti Petri puellarum" ("Monastery of the Daughters of St. Peter") or "Ecclesia que dicitur Sancti Petri puellarum" ("Church of the Daughters of St. Peter").[9]

Since its foundation, it has always had two churches. The conventual church is called Saint-Pierre. It was rebuilt in the Romanesque style in the 11th century, a style it retained until the abbey was rebuilt in the 17th century. Next door is a smaller church, Saint-Saturnin (also known as Saint-Sornin), a parish church whose revenues are collected by the nuns.

It was an aristocratic abbey, governed by nuns from the upper nobility. By the middle of the 14th century, novices had to prove at least four generations of paternal nobility[10] to be admitted to the convent. The nuns form an assembly, known as the chapter, where they elect their own abbess, who holds this position for life. The abbess is answerable only to the Pope for her election, and is in no way subject to the authority of the Archbishop of Lyon[10] She even wears the crosier like a bishop. She is the head of the convent and administers the many material assets belonging to it. In fact, the convent possessed a great deal of wealth, and was particularly well endowed with land.

From the 16th century onwards, however, discipline became less strict, and the rules of community life began to loosen: nuns often lived outside the convent in private homes, or even in pleasant townhouses between courtyard and garden, and the chapter hardly met more than once a year.[11] During a royal visit to Lyon in 1503, Louis XII and Queen Anne de Bretagne received complaints about the nuns' misconduct. The nuns were ordered to return to a life of enclosure in the abbey, and to respect the rule of Saint Benedict. Refusing this reform, which they considered too severe, the nuns, supported by their powerful families, rebelled and appealed to the Pope, their protector, to defend their rights.[11] In 1516, they voiced their discontent directly to Queen Claude of France. It was then decided to expel them from the abbey, which Archbishop François II de Rohan did. Daughters from less prestigious families were chosen to replace them. Although the abbey remained as wealthy as ever, it gradually lost its privileges and, above all, its independence: in 1637, it finally came under the authority of the Archbishop of Lyon.[8] In the meantime, the nuns were stripped of their right to appoint their own abbess, a privilege that now fell to the king himself.

The Royal Abbey and the reconstruction of the Palais Saint-Pierre

[edit]

The palace took on its present configuration in the 17th century. Of the former buildings of the Saint-Pierre-les-Nonnains convent, all that remains today is the Romanesque porch of the conventual church, dating from the reconstruction of the 11th century. In 1659, Anne de Chaulnes (circa 1625–1672), daughter of Marshal and Peer of France Honoré d'Albert and abbess from 1649 until her death, decided to rebuild what was then known as the "Royal Abbey of the Ladies of Saint-Pierre".[12] She chose Avignon architect François Royers de la Valfrenière to carry out the project. Already elderly at the time of the work (he died in 1667), the reconstruction of the palace was his major project. He designed the monumental elevation of the façade along the Place des Terreaux, as well as that of the two side façades.

The foundation stone was laid by a "poor boy" on March 16, 1659. The building designed by Royers de la Valfrenière is an imposing Roman-style palace, stretching along one long side of the Place des Terreaux.

However, when Anne de Chaulnes died in 1672, two wings had yet to be built, and work on the interior decoration had not yet begun. Her sister-in-law, Antoinette de Chaulnes (1633–1708), succeeded her as head of the abbey in 1675, and completed the project. A sumptuous interior decoration, now almost entirely lost, was executed between 1676 and 1687.[12] Part of the work was entrusted to Lyonnais painter and architect Thomas Blanchet (1614–1689), "Premier peintre de la Ville", who, since his return from Italy in 1655, had been highly regarded for his monumental decorations.When Antoinette de Chaulnes called on him, he had just demonstrated the extent of his talent by decorating the ceilings and walls of the Hôtel de Ville.[13] All that remains of his work at the Palais Saint-Pierre are the grand staircase, recently restored to its original five-window design, and the refectory, with its exuberant Baroque decor. To decorate the latter, he enlisted the help of sculptors Simon Guillaume and Nicolas Bidault, Marc Chabry, who designed the coat of arms (notably those of the Chaulnes sisters), and painter Louis Cretey, recently returned from Italy, who painted two monumental canvases at the ends of the hall, as well as three compositions decorating the oculi of the vault. All in all, the reconstruction work cost a considerable sum of 400,000 livres.[14] The palace and its new décor remained unchanged until the French Revolution.[15] Stalls were set up on the first floor of the palace during its reconstruction, to be rented out to merchants, thus generating substantial income for the abbey. At the time of its completion, the new building was Lyon's finest Baroque achievement, and its Italian scale and monumentality never ceased to fascinate visitors. In the 18th century, the abbey continued to prosper. In 1755, it was considered one of the five richest abbeys in France.[14]

Secularization of the former abbey

[edit]The French Revolution turned the place upside down, sounding the death knell for the abbey after more than a thousand years of existence. The thirty-one nuns still present at the monastery in 1790 were expelled two years later, following the decrees of August 4 and 6, 1792, which abolished religious congregations.[14] Emptied of its occupants, the palace narrowly escaped the destruction that befell so many other religious establishments during the Revolution. Although most of the interior decorations were lost when a barracks was set up in the palace in 1793, and the church of Saint-Saturnin was destroyed, the building was ultimately spared by the various town-planning projects drawn up by the revolutionaries, one of which included making openings in the middle of the building.

On June 1, 1801, the Stock Exchange moved into the former abbey. On September 1, 1801, the Chaptal decree created a fine arts museum in Lyon.[12] On July 20, 1802, the museum was installed by prefectoral decree in the former abbey. On June 25, 1802, the city allocated the Palais Saint-Pierre to public education and commercial establishments.[16]

The first museum room was opened to the public in 1803, on the second floor of the south wing, in the abbey's former boiler room.[16]

In 1835, the Faculty of Science occupied part of the former abbey. It was joined in 1838 by the Faculty of Arts.[17]

In 1860, the Palais de la Bourse was inaugurated. The stock exchange and chamber of commerce moved out of the former abbey.[17]

Architecture

[edit]The entire Palais Saint-Pierre (excluding the listed parts) has been listed as a monument historique since May 28, 1927.[18] The facades and roofs have been listed as monuments historiques since August 8, 1938.[18]

Abbey church

[edit]Saint-Pierre church is thought to have been founded in the 6th century. It is mentioned in the Leidrad writ of the 7th century. It is said to have been built by Saint Annemond and to have possessed a number of relics.[19]

It was rebuilt in the 11th century. At that time, the church stopped at the present-day steps in front of the choir, and consisted of a single nave closed by a five-sided apse. The arms of the transept are formed by the side chapels of Saint Margaret to the north and Saint Benedict to the south.

Windows from the Romanesque church, found in the interior passageway, and the porch on rue Paul-Chenavard remain. In the 14th century, side chapels were added, giving the chapel its current appearance. Part of the church was destroyed in 1562 during the Wars of Religion, by Protestants led by Baron des Adrets.

In the 18th century, architect Antoine Degérando enlarged the choir (1742)[20] and built the bell tower. In 1793, Jane Dubuisson mentions the sale and demolition of the chapel of Saint Saturnin. She also explains that St. Peter's was transformed into a saltpetre factory.[21] In 1807, Saint Pierre became a parish church. One hundred years later, in 1907, it was disused following the law separating church and state. It was assigned to the Musée des Beaux-Arts. Part of the sculpture collection is on display here.

The porch, two doors and façade have been listed as a monument historique since February 16, 1921.[22]

A second church, dedicated to Saint Saturnin and commonly called Saint-Sorlin, stood to the south of the Saint-Pierre church. It was used by the parish for baptisms and weddings.[23] It had a porch bell tower. The church was destroyed during the French Revolution.

-

Frontage on rue Paul Chenavard.

-

Detail of the porch.

-

Former nave.

-

Plan of the church in its 18th-century neighborhood.

Convent buildings

[edit]Refectory

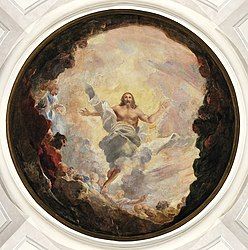

[edit]The Baroque refectory was built from 1684 onwards under the direction of Thomas Blanchet, who designed the iconography, after having created that of the grand staircase; renovated, it is now used to welcome groups. With its exuberant decor, it is one of the main testimonies to Baroque art in Lyon and to the splendor of the royal abbey of the Dames de Saint-Pierre in the 17th century. Surprisingly, it survived the revolutionary destruction of the museum's interior decor, despite the fact that religious subjects are the main theme of its decoration. The refectory features two monumental paintings facing each other on opposite walls. The theme of these paintings is linked to the meal, in keeping with the original purpose of the place. The Multiplication of the Loaves and The Last Supper decorate the east and west ends of the room, and the three lunettes (ceiling oculi): (The Assumption – The Ascension – The Prophet Elijah) by Louis Cretey. Three other paintings by Cretey decorate the ceiling oculi. The rest of the decor, made up of sculptures, was created by Nicolas Bidault (1622–1692), sculptor and medallist, and Simon Guillaume, author of 14 sculptures. Marc Chabry created the coats of arms, escutcheons and coats of arms. The coats of arms of abbesses Anne and Antoinette de Chaulnes are on the pediment of the west entrance door. The coat of arms of the King of France is on the keystone of the second vault.

Sculptures by Simon Guillaume, after drawings by Thomas Blanchet

- 1687–1689 – La Temperance – Penance – Saint Barbara – Saint Ennemond – Saint Margaret – Saint Peter denying Christ – Saint John on Patmos – The Nativity of Christ – Saint Benedict in the cave – The Baptism of Christ – Saint Catherine – Saint Anthony – Chastity – Charity

-

The Last Supper

-

View of the refectory from The Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes

-

The Multiplication of the loaves

-

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary

-

The Ascension of Christ

-

The Prophet

Cloister

[edit]

The architecture of the cloister was extensively modified in the 19th century by René Dardel and Abraham Hirsch. The murals under the arcades, featuring the names of famous Lyonnais, date from this period, as do the medallions adorning the pediments. The fountain in the circular basin at the center of the garden features an antique sarcophagus surmounted by a statue of Apollo, god of the arts. Several statues by 19th-century artists from the museum's collections have also been installed in the garden. These include works by Auguste Rodin, Léon-Alexandre Delhomme and Bourdelle. The lawn parterres are half-moon-shaped and rectangular, with trees and flowerbeds designed by architect Abraham Hirsch according to the original 17th-century plan. Open year-round from 8:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m.

Properties, land burrows, benefits

[edit](non-exhaustive list)

Abbesses

[edit](non-exhaustive list)

Foundation allegedly from the 3rd century

[edit]Alfred Coville has demonstrated the fallacious nature of the alleged foundation by Aldebert, governor of Lugdunum under Septimius Severus, and therefore of this chronology.[24]

List of abbesses

[edit]Source:[25]

- 6th century – Raymonde, daughter of Lord Rodolphe.

- 7th century – Wadelmonde, daughter of Lord Constantin.

- 7th century – Radegonde, contemporary of Saint Ennemond, died around 665.

- 7th century – Animonie, contemporary of Saint Ennemond.

- 7th century – Lucie, sister of Saint Ennemond.

- 7th century – Petronilla, sister of Saint Ennemond.

- 8th century – Dida, contemporary of Saint Fulcoad, bishop of Lyon.

- 723–750 – Marie.

- 750 – Jeanne.

- 8th century – Adalaisie, died after 780.

- 8th century – Agnes I.

- 9th century – Deidona. She was alive in 807.

- IXth century – Noémi Ire, died in 832.

- 832–850 – Pontia.

- 850–895 – Oda I.

- 895-??? – Bérarde, or Bernarde I. She lived in 900.

- ????-925 – Garamburge or Haramburge I.

- 925–988 – Elisabeth I.

- 936–988 – Rollinde.

- 988-? – Aisseline. She lived in 993.

- ?-1016 – Bérarde or Bernarde II.

- 1016–1044? – Adélaïs or Alise Artaud.

- 1044?10?? – Alix or Alise. She lived in 1044.

- 10?–1090 – Noémi II of Vanoc.

- 1090–1130 – Agnes II.

- 1130-11?? – Oda II.

- 11??-1184? – Rollande or Rollinde II. She lived in 1157.

- 1184–1194 – Loos de Forez.

- 1194-v.1198 – Garamburge or Haramburge II.

- c.1198–1220 – Agnès II de Guignes.

- 1220–1223 – Elisabeth II.

- 1223–1236 – Beatrix/Béatrice I de Savoie.

- 1236-12?? – Guillemette or Guillelmine de Forez. Sister of the Count of Forez.

- 12–44 – Bérarde or Bernarde III.

- 1244-12?? – Guillemette or Guillelmine II de Montferrand.

- 12-1254 – Agnès IV de Chalon.

- 1254-12?? – Alix/Alice/Adélaïde de Savoie, daughter of Count of Savoy Thomas I.

- 12??-12?? – Brune de Grammont.

- 12-1266 – Beatrix/Béatrice II. She is reputed to be of the royal house of Artois.

- 12-1290 – Agathe de Savoie.

- 1290–1292 – Agnès V de Beaujeu, daughter of Humbert de Beaujeu.

- 1292-1??? – Agnès VI de Charvins.

- 1???-13?? – Marguerite I de Solignac. She was abbess in 1326.

- 13?–1346 – Sibille Ire de Varennes. She was abbess in 1336.

- 1346–1353? – Gabrielle de Courtenay.

- 1353?–13?? – Agnès VII de Guignes.

- 13?–1370 – Huguette de Thurey. She was alive in 1364.

- 1370–1386 – Agathe II de Thurey, daughter of Gaspard, comté de Noyers, seigneur de Morillon, marshal of Burgundy, governor and seneschal of Lyon, niece of Philippe, archbishop of Lyon and Pierre, bishop of Marseille and cardinal.

- 1386–1390 – Richarde de Saluces.

- 1390–1435 – Antoinette de La Rochette, daughter of Jean de Seyssel, Marshal of Savoy (1436–1457) and Françoise de La Baume-Montrevel.

- 1435-14?? – Pernette, Péronne or Pétronille d'Albon, daughter of Guillaume, seigneur de Saint-Forgeux and Alix de l'Espinasse.

- 14-1455 – Alix de Vassalieu. She became abbess of Saint-André de Vienne in 1443.

- 1455–1477 – Marie d'Amanzé. She was alive in 1487. She was the daughter of Guillaume, seigneur d'Amanzé and Marguerite de Semur.

- 1477-14?? – Sibille II d'Albon.

- 14 – 1487 – Marie II d'Albon. Initially prioress of Pouilly.

- 1487–1493 – Guicharde d'Albon. Niece of Pernette, Péronne or Pétronille d'Albon, sister of Jean, abbot of Savigny, daughter of Jean, lord of Saint-André and Guillemette de Laire.

- 1493–1503 – Guillemette III d'Albon. Sister or niece of Abbess Guicharde. She was the daughter of Gilet, seigneur of Saint-André and Ouches, and Jeanne de La Palisse.

- 1503–1516 – Françoise Ire d'Albon de Saint-André. Daughter of Guichard d'Albon and Anne de Saint-Nectaire.

- 1516–1520 – Antoinette II d'Armagnac.

- 1520–1550 – Jeanne de Thouzelles.

- 1550-1550 – Marguerite II d'Amanzé.

- 1550–1599 – Françoise II de Clermont. Daughter of Antoine, viscount of Clermont and Anne de Poitiers, sister of Diane de Poitiers.

- 1600–1610 – Françoise de Beauvilliers de Saint-Aignan. Daughter of Claude, comte de Saint-Aignan and Marie Babou de La Bourdaisière. She was Madame de Clermont's niece. She was a nun at the Beaumont-les-Tours monastery before her appointment.

- 1610–1632 – Marie-Françoise de Lévis-Ventadour. Daughter of Anne de Lévis, Duc de Ventadour and Marguerite de Montmorency. She was a nun at Chelles, then coadjutor to the Abbess of Avenay, Françoise de la Marck, her maternal aunt,[26] and in 1610 swapped with Françoise de Beauvilliers. She died in 1649 or 1650.

- Romorantin. She was a nun at Jouarre before coming to Saint-Pierre.

- 1635–1648 – Élisabeth III d'Epinac. Niece of Lyon archbishop Pierre d'Epinac.

- 1649–1672 – Anne d'Albert d'Ailly de Chaulnes, decided to restore the abbey to its current state, by architect François de Royers de La Valfrenière. She was the daughter of Honoré d'Albert, Duke and Peer of Chaulnes and Marshal of France, and Charlotte d'Ailly. Prior to this, she was a professed nun at Abbaye-aux-Bois.

- 1672–1708 – Antoinette III d'Albert d'Ailly de Chaulnes de Picquigny. She continued the work undertaken by her sister and called on Thomas Blanchet.

- 1708–1738 – Guyonne-Françoise-Judith de Cossé-Brissac. She had been a nun at Panthemont and was the daughter of Timoléon, comte de Brissac, chevalier des Ordres, Grand Pannetier de France, and Marie Charron d'Ormeilles.

- 1738–1772 – Anne de Melun d'Epinoy, descendant of the Comtes de Melun and the Princes d'Epinoy. She had been a professed nun at Origny Abbey and Abbess of Cézanne.

- 1772–1790 – Marguerite-Madeleine de Monteynard, last abbess.

Religious and public figures

[edit]- 14th century – Jacquette de Chaïruygie, known for her disorders[27]

- 14th century – Antoinette de Grolée, who received the benefits of Jacquette de Chaïruygie

- S – D – Sibille d'Albon[28]

Archives

[edit]Most of the documentation concerning the abbey is held by the Rhône departmental archives. René Lacour, then chief curator, classified all these archives, then published a numerical directory in 1968 under the reference 27 H. During this period, Joseph Picot was working on his doctoral thesis, and in 1970 published a book on Saint-Pierre abbey, from its foundation to the middle of the 14th century.[29] For this, he consulted the archives of the Rhône, Isère and Ain departments, the Archives municipales de Lyon, as well as the municipal libraries of Lyon and Le Puy.[30]

Bibliography

[edit]- Charvet, Léon (1869). "François de Royers de La Valfenière et l'abbaye royale des bénédictines de Saint-Pierre à Lyon". Mémoires de la Société littéraire de Lyon – Année 1868. pp. 121–234.

- Charvet, Léon (1869). "François de Royers de La Valfenière et l'abbaye royale des bénédictines de Saint-Pierre à Lyon (suite)". Revue du Lyonnais. 3 (8): 464–487.

- Charvet, Léon (1870). "François de Royers de La Valfenière et l'abbaye royale des bénédictines de Saint-Pierre à Lyon (suite)". Revue du Lyonnais. 3 (9): 36–49, 95–131.

- Coville, Alfred (1904). "Une aubaine à Lyon sous Henri II". Revue historique (85): 68–85.

- Coville, Alfred (1928). Recherches sur l'histoire de Lyon du Ve au IXe siècle (450–800). Paris: Picard.

- Perrat, Charles (1929). Compte-rendu de lecture sur "Recherches sur l'histoire de Lyon du ve au ixe siècle (450–800)" d'Alfred Coville. Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. pp. 378–380.

- Hervier, Marcel (1922). Le Palais des Arts, ancienne abbaye royale des dames de Saint-Pierre, sa construction, son histoire. Lyon: Imp. Audin. p. 66.

- Hervier, Marcel (1921). "Notes sur l'histoire religieuse à Lyon- La vocation forcée d'Anne-Marie Pestallozi, religieuse de St Pierre de Lyon au XVIIIe siècle". La Revue du Lyonnais. Audin et Cie.

- Picot, Joseph (1970). l'Abbaye de Saint-Pierre de Lyon. Paris: Les Belles-Lettres. pp. 8 cartes et plans-264.

- Lacour, René (1970). Compte-rendu de lecture sur "L'abbaye de Saint-Pierre de Lyon" de Joseph Picot. Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. pp. 497–501.

- Wollasch, Joachim (1973). "Compte-rendu de lecture sur "L'abbaye de Saint-Pierre de Lyon" de Joseph Picot". Cahiers de civilisation médiévale (64): 342.

- Steyert, André (1887). "La merveilleuse histoire de l'esprit qui est apparu aux religieuses de Saint-Pierre à Lyon en l'année 1527". étude historique et bibliographique. Imprimerie Mongin-Rusand 3 rue Stelle à Lyon.

- Collectif (1984). Le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon de A à Z. Fage éditions. ISBN 2849751642.

- Banel-Chuzeville, Nathalie, ed. (2009). Le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon de A à Z (2nd ed.). Lyon: Fage. ISBN 2849751642.

- Le Febvre, Isaac (1627). "Nombre des églises qui sont dans l'enclos et dépendances de la ville de Lyon : Avec une exacte recherche du temps et par qui elles y ont été fondées". Collection Lyonnaise. 6: 48–49.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bénasse, Pierre-Maurice (2010). Les Six Naissances de l'Abbaye royale des Bénédictine de Saint-Pierre de Lyon. musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. p. 9.

- ^ "Testament de saint Ennemond 655 ou XIIè-XIIIè s." musée du diocèse de lyon.

- ^ Lacour (1970, p. 498)

- ^ a b Wollasch (1973, p. 342)

- ^ de Moydieu, Berger. Tableau historique de l'abbaye royale de S. Pierre... Second manuscrit, revu, corrigé et augmenté. 1783.

- ^ Bénasse, Pierre-Maurice (2010). Les Six Naissances de l'Abbaye royale des Bénédictine de Saint-Pierre de Lyon. musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. p. 14.

- ^ Picot (1970, p. 20)

- ^ a b Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 46.

- ^ a b Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 97.

- ^ a b Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Durey, Philippe (1988). Le musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Paris: Albin Michel. p. 9.

- ^ Galactéros de Boissier, Lucie (1991). Thomas Blanchet, 1614–1689. Paris: Arthéna.

- ^ a b c Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 165.

- ^ Banel-Chuzeville 2009, p. 135.

- ^ a b Vaisse, Pierre (2007). L'esprit d'un siècle : Lyon 1800–1914. Lyon: Fage Éditions. p. 314.

- ^ a b Vaisse, Pierre (dir.). op. cit. p. 315.

- ^ a b "Palais Saint-Pierre ou ancienne abbaye des Dames de Saint-Pierre". Plateforme ouverte du patrimoine.

- ^ Le Febvre (1627, p. 48)

- ^ Ramond, Sylvie (dir) (2009). Le musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, de A à Z. Lyon: Fage.

- ^ Dubuisson, Jane. L'abbaye saint Pierre aujourd'hui, palais du commerce et des arts" dans Lyon, ancien et moderne, par les collaborateurs de la revue du Lyonnais (direction Léon Boitel). Lyon. pp. 69–90.

- ^ "Eglise Saint-Pierre-des-Terreaux". Plateforme ouverte du patrimoine.

- ^ Le Febvre (1627, p. 49)

- ^ Perrat (1929, p. 378)

- ^ Supplément aux (in French).

- ^ texte, Académie nationale de Reims Auteur du (1876). "Travaux de l'Académie nationale de Reims". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ Clerjeon, Pierre (1829). Histoire de Lyon depuis sa fondation jusqu'à nos jours. chez Théodore Laurent. p. 469.

- ^ Le Laboureur, Claude (1681). Les Mazures de l'Abbaye de l'Isle-Barbe ..., généalogie des d'Albon. Vol. 2. chez Carlerot. pp. 145 & 674.

- ^ Lacour (1970, p. 498)

- ^ Lacour (1970, p. 500)