2 Samuel 13

| 2 Samuel 13 | |

|---|---|

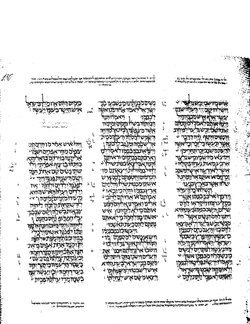

The pages containing the Books of Samuel (1 & 2 Samuel) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | First book of Samuel |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 3 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 10 |

2 Samuel 13 is the thirteenth chapter of the Second Book of Samuel in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible or the second part of Books of Samuel in the Hebrew Bible.[1] According to Jewish tradition the book was attributed to the prophet Samuel, with additions by the prophets Gad and Nathan,[2] but modern scholars view it as a composition of a number of independent texts of various ages from c. 630–540 BCE.[3][4] This chapter contains the account of David's reign in Jerusalem.[5][6] This is within a section comprising 2 Samuel 9–20 and continued to 1 Kings 1–2 which deal with the power struggles among David's sons to succeed David's throne until 'the kingdom was established in the hand of Solomon' (1 Kings 2:46).[5]

Text

[edit]This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 39 verses.

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[7] Fragments containing parts of this chapter in Hebrew were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls including 4Q51 (4QSama; 100–50 BCE) with extant verses 1–6, 13–34, 36–39.[8][9][10][11]

Extant ancient manuscripts of a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint (originally was made in the last few centuries BCE) include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[12][a]

Analysis

[edit]This chapter can be divided into two sections:[14]

The two sections parallel each other:[14]

- A plan was hatched

- King David was consulted

- Violence erupted

Both sections opened with the same phrase construction hyh + l + Absalom to report that Absalom "had" a sister (13:1) and Absalom "had" sheep shearers (13:23).[15] The victims in both sections unwittingly entered the domains of their attackers, made available to their assailants by King David, with the violence happening around food.[15] The difference is the lengthy description for Tamar's care to her predator before the rape in contrast to very little attention to Amnon before the murder, perhaps to show that Amnon was not an innocent victim.[15]

David played a key role in both episodes, in the first by providing Amnon access to Tamar and in the second by allowing Amnon and Absalom to get together, but crucially, David failed to exact justice for Tamar, and this incited Absalom, Tamar's brother, to take a role of "judge" to punish Amnon by killing him and later he openly took that role (2 Samuel 15) to bolster support for his rebellion against David.[16] These episodes involving Amnon, Tamar, and Absalom have direct bearing on David's succession issue.[17]

Amnon raped Tamar (13:1–22)

[edit]

The crown-prince of Israel, Amnon, son of David and Ahinoam, was deeply attracted to Tamar, full sister of Absalom, both children of David and Maacah. Apparently virgins were under close guard, so Amnon did not have direct access to Tamar (verse 3), so he had to use trickery suggested by his cousin Jonadab (verses 3–5) to get Tamar come to take care of him (under the pretense of being sick) with David's permission.[17] When left alone with Tamar, Amnon raped his sister, ignoring Tamar's plea for having a proper way of marriage, because Amnon was driven not by love but by lust.[17] Although marriage between blood siblings was recorded in the early part of Hebrew Bible, cf. Genesis 20:12, it was later prohibited by Torah, cf. Leviticus 18:9, 11; 20:17; Deuteronomy 27:22.[17] However, the rabbis point out that Tamar was born from David's union with a beautiful captive woman, and that her mother conceived of her during the first act, in which case, the mother had not yet converted to Judaism and the child born of this union had also not yet entered the Jewish community.[18] Tamar required a conversion to the Jewish religion, and although Amnon and Tamar had the same biological father, they were not considered bona-fide siblings and could actually marry each other, as she was a proselyte to the Jewish religion. For this reason, Tamar insisted that their father would not withhold her from him (2 Samuel 13:13).[19]

Whether this was known to Amnon or not, after the rape, Amnon felt an intense loathing of Tamar, and Tamar's expectation that Amnon would marry her (verse 16, cf. Exodus 22:16; Deuteronomy 22:28), she was expelled from his sight with contempt (verses 15,17–18).[20] Tamar immediately went into mourning, by tearing the long gown she was wearing as a virgin princess, as a sign of grief rather than lost virginity, as well as putting ashes on the head and placing a hand on the head (cf. Jeremiah 2:37).[21] Verse 21 notes that David was very angry when he heard, but he did not take any action against Amnon; the Greek text of Septuagint and 4QSama have a reading not found in the Masoretic Text as follows: 'but he would not punish his son Amnon, because he loved him, for he was his firstborn' (NRSV; note in ESV). Absalom would have resented David's leniency, but he restrained himself (verse 22) for two years (verse 23), while made a good plan for revenge.[21]

This section has a structure that meticulously places the rape at the center:[22]

- A. The characters and their relationships (13:1–3)

- B. Planning the rape (13:4–7)

- B1. Jonadab's advice to Amnon (13:4–5)

- B2. David provides Amnon access to Tamar (13:6–7)

- C. Tamar's actions (13:8–9)

- D. Tamar comes into the inner room (13:10)

- E. The dialogue before the rape (13:11)

- E1. Amnon orders Tamar (13:12–13)

- E2. Tamar protests (13:11–14a)

- E3. Amnon will not listen to Tamar (13:14a)

- F. The rape (13:14b)

- E'. The dialogue after the rape (13:15–16)

- E1'. Amnon orders Tamar (13:15)

- E2'. Tamar protests (13:16ab)

- E3'. Amnon will not listen to Tamar (13:16c)

- E. The dialogue before the rape (13:11)

- D'. Tamar is thrown out of the room (13:17–18)

- D. Tamar comes into the inner room (13:10)

- C'. Tamar's actions (13:19)

- B'. The aftermath of the rape (13:20–21)

- B1'. Absalom's advice to Tamar (13:20)

- B2'. David's reaction (13:31)

- B. Planning the rape (13:4–7)

- A.' New relationships among the characters (13:22)[22]

The episode began with a description of the relationships among the characters (A), which is permanently ruptured at the end (A'). David's actions (B/B') and Tamar actions (C/C') bracket the center action which is framed by the entrance/exit of Tamar from the room (D/D') and the verbal confrontations between Amnon and Tamar (E/E').[22]

Verse 3

[edit]- But Amnon had a friend, whose name was Jonadab, the son of Shimeah, David's brother. And Jonadab was a very crafty man.[23]

- "Jonadab": according to the Masoretic Text and Septuagint. The Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4QSama wrote the name "Jonathan" (both appearances in this verse).[24]

Absalom's revenge on Amnon (13:23–39)

[edit]The revenge of Absalom toward Amnon was timed to coincide with sheep-shearing festivities at Baal-hazor near Ephraim, which was probably a few miles from Jerusalem, as it was perfectly reasonable for Absalom to invite the king and his servants to the celebrations. David was said to have a slight suspicion of Absalom's personal invitation (verse 24), so he did not go, but was persuaded by Absalom for his permission to allow Amnon to go (verses 25, 27).[21] Apparently David did not realize the extent of Absalom's hatred until he was briefed by Jonadab (cf. verse 32). According to the Septuagint and 4QSama, 'Absalom made a feast like a king's feast' (NRSV). The murderers were only identified as Absalom's servants (verse 29) and it is obvious that Absalom gave the order to kill and encouraged them.[21] An initial report that all the king's sons had been killed had to be corrected by Jonadab, asserting that it was only Amnon who had died and providing David the information of the reason for Absalom's action (verse 32), then the king's sons indeed returned along the 'Horonaim road' (the Septuagint Greek version reads 'the road behind him').[21] During the period of court mourning for Amnon (verses 36–37), Absalom took refuge with Talmai, king of Geshur, his grandfather on his mother's side, and stayed there in exile for three years (verses 37–38).[21] Fast forward to the end of three years, the narrative records a change in David's 'change of heart' (following the LXX and 4QSama), attributed to his affection for all his sons and perhaps also the realization that Absalom was second in line for succession, thus preparing the way for Absalom's return which is reported in chapter 14.[21] Absalom's temporary exclusion from court was followed by brief reconciliation with David, but Absalom soon set a rebellion (chapters 15–19) which ultimately caused his death, a chain of events which is attributed to the clash of personalities shown in this chapter and chapter 14 between the vindictive (14:33) and determined (14:28–32) Absalom in contrast to the compliant (13:7), indecisive (14:1), and lenient (13:21) David.[17]

The structure in this section centers to the scene of Jonadab informing David that Absalom murdered Amnon for the rape of Tamar:[15]

- A. Absalom and David (13:23–27)

- B. Absalom acts (13:28–29a)

- C. Flight of the king's sons and a first report to David (13:29b–31)

- D. Jonadab's report: only Amnon among the king's sons was dead (13:32a)

- E. Jonadab informs David of Absalom's motives: because Amnon raped Tamar (13:32b)

- D'. Jonadab's report: only Amnon among the king's sons was dead (13:33)

- D. Jonadab's report: only Amnon among the king's sons was dead (13:32a)

- C'. Flight of Absalom and a second report to David (13:34–36)

- C. Flight of the king's sons and a first report to David (13:29b–31)

- B'. Absalom acts (13:37–38)

- B. Absalom acts (13:28–29a)

- A'. Absalom and David (13:39)[25]

Tamar tried to prevent Amnon from raping her by warning that the action would lead to him being considered a nabal, a Hebrew word for "scoundrel" (2 Samuel 13:13). This epithet connects the story of Amnon's murder to the death of Nabal, the first husband of Abigail, (1 Samuel 25) as follows:[26]

- Both episodes took place during sheep-shearing season (1 Samuel 25:2; 2 Samuel 13:24)

- Nabal and Absalom held celebrations fit for a king (1 Samuel 25:36; 2 Samuel 13:27)

- Nabal and Amnon had hearts merry with wine (leb tob) before their death (1 Samuel 25:36; 2 Samuel 13:28)

- Both Nabal and Amnon (labeled as nabal) died

Verse 37

[edit]- But Absalom fled, and went to Talmai, the son of Ammihud, king of Geshur. And David mourned for his son every day.[27]

- "Absalom fled": this phrase was repeated three times in verses 34, 37 and 38, to emphasize that David had then lost three sons: the firstborn of his and Bathseba, Amnon and also Absalom (rebelling and eventually died in that rebellion), whereas the third time of the use (verse 38) is to indicate David's change of heart as his animus to Absalom subsided as he was more at ease with the death of Amnon.[28]

See also

[edit]- Related Bible parts: 2 Samuel 14

Notes

[edit]- ^ The whole book of 2 Samuel is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Halley 1965, p. 184.

- ^ Hirsch, Emil G. "SAMUEL, BOOKS OF". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Knight 1995, p. 62.

- ^ Jones 2007, p. 197.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Coogan 2007, p. 459 Hebrew Bible.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Ulrich 2010, pp. 303–306.

- ^ Dead sea scrolls - 2 Samuel

- ^ Fitzmyer 2008, p. 35.

- ^ 4Q51 at the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Morrison 2013, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d Morrison 2013, p. 177.

- ^ Morrison 2013, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d e Jones 2007, p. 222.

- ^ Zechariah ha-Rofé 1992, p. 419.

- ^ 2 Samuel 13:13

- ^ Jones 2007, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jones 2007, p. 223.

- ^ a b c Morrison 2013, p. 167.

- ^ 2 Samuel 13:3 ESV

- ^ Steinmann 2017, p. 234.

- ^ Morrison 2013, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Morrison 2013, p. 180.

- ^ 2 Samuel 13:37 KJV

- ^ Steinmann 2017, pp. 253–254.

Sources

[edit]Commentaries on Samuel

[edit]- Auld, Graeme (2003). "1 & 2 Samuel". In James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Bergen, David T. (1996). 1, 2 Samuel. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805401073.

- Chapman, Stephen B. (2016). 1 Samuel as Christian Scripture: A Theological Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1467445160.

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Samuel 12 – 2 Samuel 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 978-1451469233.

- Evans, Paul (2018). Longman, Tremper (ed.). 1-2 Samuel. The Story of God Bible Commentary. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0310490944.

- Gordon, Robert (1986). I & II Samuel, A Commentary. Paternoster Press. ISBN 9780310230229.

- Hertzberg, Hans Wilhelm (1964). I & II Samuel, A Commentary (trans. from German 2nd edition 1960 ed.). Westminster John Knox Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0664223182.

- Morrison, Craig E. (2013). Berit Olam: 2 Samuel. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814682913.

- Steinmann, Andrew (2017). 2 Samuel. Concordia commentary: a theological exposition of sacred scripture. Concordia Publishing House. ISBN 9780758650061.

- Zechariah ha-Rofé (1992). Havazelet, Meir (ed.). Midrash ha-Ḥefetz (in Hebrew). Vol. 2. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. OCLC 23773577.

General

[edit]- Breytenbach, Andries (2000). "Who Is Behind The Samuel Narrative?". In Johannes Cornelis de Moor and H.F. Van Rooy (ed.). Past, Present, Future: the Deuteronomistic History and the Prophets. Brill. ISBN 9789004118713.

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195288810.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802862419.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300188271.

- Jones, Gwilym H. (2007). "12. 1 and 2 Samuel". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 196–232. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Klein, R.W. (2003). "Samuel, books of". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837844.

- Knight, Douglas A (1995). "Chapter 4 Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In James Luther Mays, David L. Petersen and Kent Harold Richards (ed.). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567292896.

- McKane, William (1993). "Samuel, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Ulrich, Eugene, ed. (2010). The Biblical Qumran Scrolls: Transcriptions and Textual Variants. Brill.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jewish translations:

- Samuel II - II Samuel - Chapter 13 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Samuel chapter 13 Bible Gateway