2020s in African history

The history of Africa in the 2020s covers political events on the continent, other than elections, from 2020 onwards.

International events in Africa

[edit]Major drought in Southern Africa

[edit]In 2024, a drought and subsequent food shortages in Southern Africa threatened to become a major humanitarian catastrophe, according to warnings by the United Nations.[1]

History by country

[edit]Algeria

[edit]In July 2021, Amnesty International and Forbidden Stories reported, that Morocco had targeted more than 6,000 Algerian phones, including those of politicians and high-ranking military officials, with the Pegasus spyware.[2][3] In August 2021, Algeria blamed Morocco and Israel of supporting the Movement for the self-determination of Kabylia, which the Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune accused of being involved in the wildfires in northern Algeria. Tebboune accused Morocco for perpetrating hostile acts.[4] In the same month, King Mohammed VI of Morocco reached out for reconciliation with Algeria and offered assistance in Algeria's battle against the fires.[5] Algeria did not respond to the offer.[6]

On 18 August 2021, Tebboune chaired an extraordinary meeting of the High Security Council[7] to review Algeria's relations to Morocco. The president ordered an intensification of security controls at the borders.[8][9][10] On 24 August 2021, Algerian foreign minister Ramtane Lamamra announced the break of diplomatic relations with Morocco.[11][12] On 27 August 2021, Morocco closed the country's embassy in Algiers, Algeria.[13] Furthermore, on 22 September 2021, Algeria's Supreme Security Council determined to close its airspace to all Moroccan civilian and military aircraft.[14]

Burkina Faso

[edit]

A coup d'état was launched in Burkina Faso on 23 January 2022.[15] Gunfire erupted in front of the presidential residence in the Burkinabé capital Ouagadougou and several military barracks around the city.[16] Soldiers were reported to have seized control of the military base in the capital.[17] The government denied there was an active coup in the country.[18] Several hours later, President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was reported to have been detained by the soldiers at the military camp in the capital.[19] On 24 January, the military announced on television that Kaboré had been deposed from his position as president.[20] After the announcement, the military declared that the parliament, government and constitution had been dissolved.[21] The coup d'état was led by military officer Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba.[22]

A statement from the Twitter account of Roch Marc Christian Kaboré urged dialogue and invited the opposing soldiers to lay down arms but did not address whether he was in detention.[23] Meanwhile, soldiers were reported to have surrounded the state news station RTB.[24] AFP News reported the president had been arrested along with other government officials.[25] Two security officials said at the Sangoulé Lamizana barracks in the capital, "President Kaboré, the head of parliament, and the ministers are effectively in the hands of the soldiers."[25]

Military captain Sidsoré Kader Ouedraogo said the Patriotic Movement for Safeguarding and Restoration "has decided to assume its responsibilities before history." In a statement, he said soldiers were putting an end to Kaboré's presidency because of the deteriorating security situation amid the deepening Islamic insurgency and the president's inability to manage the crisis. He also said the new military leaders would work to establish a calendar "acceptable to everyone" for holding new elections, without giving further details.[26] ECOWAS and African Union suspended Burkina Faso's membership in the aftermath of the coup.[27][28] On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution and appointed Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba as interim president.[29]

Damiba's rule was unpopular and lasted only 8 months, until he himself was deposed in the subsequent coup d'état in September 2022.Chad

[edit]Presidential elections were held in Chad on 11 April 2021. Incumbent Idriss Déby, who served five consecutive terms since seizing power in the 1990 coup d'état, was running for a sixth. Déby was described as an authoritarian by several international media sources, and as "strongly entrenched". During previous elections, he forbade the citizens of Chad from making posts online, and while Chad's total ban on social media use was lifted in 2019, restrictions continue to exist.

Provisional results released on April 19 showed that incumbent president Idriss Déby won reelection with 79% of the vote.[30] However, on 20 April it was announced by the military that Déby had been killed in action while leading his country's troops in a battle against rebels calling themselves the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT).[31][32]

Following president Déby's death, a body called the Transitional Military Council – led by his son Mahamat Déby Itno, dissolved the government and the legislature, and proclaimed that it would be assuming power for a period of 18 months. Thereafter, a new presidential election would be held.[33] Some political actors within Chad have labeled the installing of the transitional military government a "coup", as the constitutional provisions regarding the filling of a presidential vacancy were not followed.[34] Namely, according to the constitution, the President of the National Assembly, Haroun Kabadi, should have been named Acting President after Déby's death, and an early election called within a period of no less than 45 and no more than 90 days from the time of the vacancy.[35]

Democratic Republic of Congo

[edit]Thirty-two members of the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of the Congo died of COVID-19.[36]

Eswatini

[edit]The Prime Minister Ambrose Mandvulo Dlamini died of COVID-19 in 2020.[37]

A series of protests in Eswatini against the monarchy and for democratisation began in late June 2021. Starting as a peaceful protest on 20 June, they escalated after 25 June into violence and looting over the weekend as the government took a hardline stance against the demonstrations and prohibited the delivery of petitions.

Ethiopia

[edit]Tensions began to rise again between Ethiopia and Eritrea, after several years of efforts to negotiate peace, due to possible border disputes.[38][39][40]

After having won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's government adopted some policies which raised some concerns about political developments in Ethiopia. Abiy dissolved the governing coalition and formed a new party, the Prosperity Party; some said the imposition of a brand-new political party was detrimental to political stability. Also, the government enacted some restrictions on some forms of expression which raised concern about standards of free speech.[41][42] Abiy's response to rebel groups has raised some concerns about undue harshness, although some others allege that he was originally too lenient.[43][44] Amnesty International raised concerns about the status of one opposition leader.[45][46] Abiy encouraged Ethiopian refugees to return home, due to improving conditions.[47]

On November 4, 2020, the Ethiopian National Defense Force launched a civil war against the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) in the Tigray Region, which it claimed was in response to an attack on its troops.[48] This followed month of feuding between the central and regional governments over elections and funding.[48] The Tigray forces launched rockets at the airport of Asmara, capital of neighbouring Eritrea, claiming that forces from there had taken part in the offensive.[49] Amnesty International reported that a massacre had taken place in Tigray, with TPLF-affiliated forces claimed to be responsible.[50]

Concurrently, there was also another conflict ongoing in the Oromia Region,[48] as well as also ongoing Afar–Somali clashes between the Afar and Somali Regions of Ethiopia.[51] In October 2020, 27 people were killed. On 2 April 2021, 100 cattle herders were reportedly shot dead.[52][53] On July 24, 2021, clashes erupted in the town of Garbaiisa, the clashes killing 300 were followed by massive protests in the Somali region resulting in the only road and rail line that goes into Djibouti where 95% of Ethiopia's maritime trade goes though.[54]

Gabon

[edit]On 30 August 2023, a coup d'état occurred in the Gabonese Republic shortly after the announcement that incumbent president Ali Bongo Ondimba had won the general election held on 26 August. Following presidential elections held on 26 August 2023, the incumbent president, Ali Bongo, who had been seeking re-election for a third term, was declared the winner according to an official announcement made on 30 August.[55] However, allegations of electoral fraud and irregularities immediately emerged from opposition parties and independent observers, casting doubt over the legitimacy of the election results. Amidst growing scrutiny and widespread protests over the conduct of the elections, the Armed Forces of Gabon launched a pre-dawn coup on 30 August. Soldiers led by high-ranking officers seized control of key government buildings, communication channels, and strategic points within the capital Libreville.[56][57][58] Gunfire was also heard in the city.[59]

Guinea

[edit]In 2020, President of Guinea Alpha Condé changed the constitution by referendum to allow himself to secure a third term, a controversial change which spurred the 2019–2020 Guinean protests. During the last year of the second term and his third term, Condé cracked down on protests and on opposition candidates, some of whom died in prison, while the government struggled to contain price increases in basic commodities.[60] On 5 September 2021, Condé was captured by the country's armed forces in a coup d'état after gunfire in the capital, Conakry. Special forces commander Mamady Doumbouya released a broadcast on state television announcing the dissolution of the constitution and government.[61]

Guinea-Bissau

[edit]A coup d'état was attempted in Guinea-Bissau on 1 February 2022.[62][63][64] A few hours later, president Umaro Sissoco Embaló declared the coup over, he said that "many" members of the security forces had been killed in a "failed attack against democracy."[65]

Kenya

[edit]The Camp Simba attack by Al-Shabaab in January 2020 killed three Americans.[66]

Lesotho

[edit]On 10 January 2020, an arrest warrant was issued for First Lady Maesiah Thabane, who was wanted in connection with the 2017 murder of Lipolelo Thabane.[67] Maesaih Thabane went into hiding and Prime Minister Tom Thabane announced his intent to resign from office shortly after her arrest warrant was issued.[67] On 20 February 2020, police announced that Thabane would also be charged with murder in the case.[68]

Libya

[edit]Current crisis

[edit]

(For a more detailed map, see military situation in the Libyan Civil War)

The Libyan crisis[69][70] is the current humanitarian crisis[71][72] and political-military instability[73] occurring in Libya, beginning with the Arab Spring protests of 2011, which led to two civil wars, foreign military intervention, and the ousting and death of Muammar Gaddafi. The first civil war's aftermath and proliferation of armed groups led to violence and instability across the country, which erupted into renewed civil war in 2014. The second war lasted until October 23, 2020, when all parties agreed to a permanent ceasefire and negotiations.[74]

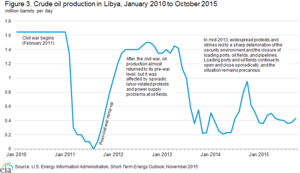

The crisis in Libya has resulted in tens of thousands of casualties since the onset of violence in early 2011. During both civil wars, the output of Libya's economically crucial oil industry collapsed to a small fraction of its usual level, despite having the largest oil reserves of any African country, with most facilities blockaded or damaged by rival groups.[75][76]

Since March 2022, two different governments control the country, the Tripoli-based and internationally recognized Government of National Unity, which controls the western part of the country and is led by Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, and the House of Representatives-recognized Government of National Stability, which controls the central and eastern part of Libya and is led by Osama Hamada.[77]

New developments

[edit]A conference between representatives of Mediterranean Basin powers implicated in the Libyan armed conflict as well as Algeria, the Republic of Congo and major world powers took place in Berlin on 19 January 2020,[78] declaring a 55-point list of Conclusions, creating a military 5+5 GNA+LNA followup committee, and an International Follow-up Committee to monitor progress in the peace process.[79] In the intra-Libyan component of the 3-point process, the economic track was launched on 6 January 2020 in a meeting in Tunis between a diverse selection of 19 Libyan economic experts.[80] The military track of the intra-Libyan negotiations started on 3 February with the 5+5 Libyan Joint Military Commission meeting in Geneva, between 5 senior military officers selected by the GNA and 5 selected by the LNA leader Khalifa Haftar. A major aim was to negotiate detailed monitoring to strengthen the 12 January ceasefire.[81][82] The intra-Libyan political track was started on 26 February 2020 in Geneva.[83] Salamé resigned from his UNSMIL position in early March 2020.[84]

A 21 August 2020 announcement by GNA leader Fayez al-Sarraj and Aguila Saleh for the LNA declared a ceasefire, lifting of the oil blockade, the holding of parliamentary and presidential elections in March 2021, and a new joint presidential council to be guarded by a joint security force in Sirte.[85] Followup meetings took place in Montreux on 7–9 September with support from UNSMIL and the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and, between five GNA and five House of Representatives (HoR) members on 11 September, in Bouznika. Both meetings appeared to achieve consensus.[86][87]

The three-track intra-Libyan negotiations, chaired by Stephanie Williams of UNSMIL, continued following the August ceasefire and September Montreux meeting,[88] with the political track evolving into the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum,[89] and the military track leading to a 24 October 2020 agreement on a permanent ceasefire.[90]

Malawi

[edit]The Constitutional Court ordered a re-run of the 2019 Malawian general election following “widespread, systematic and grave” problems with the process, leading to the 2020 Malawian presidential election.[91]

Mali

[edit]On 18 August 2020, elements of the Malian Armed Forces began a coup.[92][93] Soldiers on pick-up trucks stormed the Soundiata military base in the town of Kati, where gunfire was exchanged before weapons were distributed from the armory and senior officers arrested.[94][95] Tanks and armoured vehicles were seen on the town's streets,[96] as well as military trucks heading for the capital, Bamako.[97] The soldiers detained several government officials including the President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta who resigned and dissolved the government.[98]

The 2021 Malian coup d'état began on the night of 24 May 2021 when the Malian Army led by Vice President Assimi Goïta[99] captured President Bah N'daw,[100][101] Prime Minister Moctar Ouane and Minister of Defence Souleymane Doucouré.[102] Assimi Goïta, the head of the junta that led the 2020 coup d'état, announced that N'daw and Ouane were stripped of their powers and that new elections would be held in 2022. It is the country's third coup d'état in ten years, following the 2012 and 2020 military takeovers with the latter only having happened nine months earlier. The African Union suspended the country's membership in response.[36] On July 20, a knifeman wounded President Goïta in the arm at a mosque in Bamako in an attack described as an assassination attempt.[103]

Morocco

[edit]In November 2020, the Polisario Front declared it had broken a 30-year truce and attacked Moroccan forces in Western Sahara as part of the Western Sahara conflict.[104]

Mozambique

[edit]The insurgency in Cabo Delgado intensified with events such as the 2020 Mozambique attacks, the Mocímboa da Praia offensive in 2020 and the Battle of Palma in 2021.

Niger

[edit]The 2021 Nigerien coup attempt occurred on 31 March 2021 at around 3:00 am WAT (2:00 am UTC) after gunfire erupted in the streets of Niamey, the capital of Niger, two days before the inauguration of president-elect Mohamed Bazoum. The coup attempt was staged by elements within the military, and was attributed to an Air Force unit based in the area of the Niamey Airport. The alleged leader of the plot was Captain Sani Saley Gourouza, who was in charge of security at the unit's base.[105] After the coup attempt was foiled, the perpetrators were arrested.[106]

On 26 July 2023, a coup d'état occurred in Niger, during which the country's presidential guard removed and detained president Mohamed Bazoum. Subsequently, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, the Commander of the Presidential Guard, proclaimed himself the leader of the country and established the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland, after confirming the success of the coup.[107][108][109][110]

In response to this development, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) issued an ultimatum on 30 July, giving the coup leaders in Niger one week to reinstate Bazoum, with the threat of international sanctions and potential use of force.[111][112] When the deadline of the ultimatum expired on 6 August, no military intervention was initiated; however, on 10 August, ECOWAS took the step of activating its standby force.[113][114][115][116] Previously in 2017, ECOWAS had launched a military intervention to restore democracy in The Gambia during a constitutional crisis within the country.

All active member states of ECOWAS, except for Cape Verde, pledged to engage their armed forces in the event of an ECOWAS-led military intervention against the Nigerien junta.[117] Conversely, the military juntas in Burkina Faso and Mali announced they would send troops in support of the junta were such a military intervention launched while forming a mutual defense pact.[118][119]

On 24 February 2024, ECOWAS announced that it was lifting sanctions on Niger, purportedly for humanitarian purposes.[120]

Nigeria

[edit]The End SARS movement protested the abuses committed by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, but were met with violence which killed at least 12 people.[121]

Somalia

[edit]On 14 April 2021, acting President Somalia Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed signed a law which extended his mandate by two years. This was opposed by opposition leaders which called it "a threat to the stability, peace and unity" and by the international community.[122] On 25 April 2021, soldiers - mainly from Hirshabelle - entered Mogadishu in response. Rebels seized northern part of the city clashing with pro-government forces in some neighborhoods. Pro-government soldiers attacked homes of former Somali president and opposition leader. By the end of the day government forces withdrew towards Villa Somalia.[123] On 6 May 2021, soldiers agreed to withdraw from Mogadishu after series of talks with the Prime Minister, held by the opposition. The police were set to take control of the city.[124]

The 2021 Somali political crisis was triggered after president Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed's term ended on 8 February 2021.[125] Political turmoil escalated, with anti-government protests occurring after the government's decision to delay the 2021 Somali presidential election. Tensions rose when heavy gunfire was reported during demonstrations on 19–20 February in Mogadishu. The protesters were aiming to stage protest rallies over the next weeks and call for the 2021 Somali presidential election to be scheduled as quick as possible to end the political crisis and turmoil.[126][127][128]

On 27 December 2021, President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed announced the suspension of Prime Minister Mohammed Hussein Roble for suspected corruption, which was described by Roble as a coup attempt.[129] The next day, hundreds of soldiers loyal to Roble armed with rocket grenades and machine guns encircled the presidential palace.[130][131]

Presidential elections were held in Somalia on 15 May 2022.[134] The election was held indirectly and after the elections for the House of the People, which began on 1 November 2021 and ended on 13 April 2022.[135]

After three rounds, involving 38 candidates, parliamentary officials counted more than 165 votes in favour of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, more than the number required to defeat the incumbent president. He was declared president in a peaceful transition of power after the incumbent president conceded defeat and congratulated the victor.[136] Celebratory gunfire rang out in parts of Mogadishu.[137] The United Nations in Somalia welcomed the conclusion of the election, praising the “positive” nature of the electoral process and peaceful transfer of power.[138]

South Africa

[edit]Former president Jacob Zuma was taken into custody after declining to testify at the Zondo Commission, an inquiry into allegations of corruption during his term as president from 2009 to 2018. The Constitutional Court reserved judgement on Zuma's application to rescind his sentence on 12 July 2021.[139][140][141]

Riots and protests took place in South Africa from Friday, 9 July 2021 until Saturday, 17th July 2021, in response to the arrest of Zuma. The riots triggered wider rioting and looting fueled by job layoffs and economic inequality worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.[142][143] The unrest began in the province of KwaZulu-Natal on the evening of 9 July,[144] and spread to the province of Gauteng on the evening of 11 July.[145][146]

South Sudan

[edit]The South Sudanese Civil War ended with a negotiated peace treaty. In January 2020, the Community of Sant'Egidio mediated a Rome Peace Declaration between the SSOMA and the South Sudanese government.[147] The most contentious issue delaying the formation of the unity government was whether South Sudan should keep 32 or return to 10 states. On 14 February 2020, Kiir announced South Sudan would return to 10 states in addition to three administrative areas of Abyei, Pibor, and Ruweng,[148][149] and on 22 February Riek Machar was sworn in as first vice president for the creation of the unity government, ending the civil war.[150] Disarmament campaigns led by the government has led to resistance, with clashes killing more than 100 people in two days in north-central Tonj in August 2020.[151]

Sudan

[edit]In January 2020, progress was made in peace negotiations, in the areas of land, transitional justice and system of government issues via the Darfur track of negotiations. SRF and Sovereignty Council representatives agreed on the creation of a Special Court for Darfur to conduct investigations and trials for war crimes and crimes against humanity carried out during the War in Darfur by the al-Bashir presidency and by warlords. Two Areas negotiations with SPLM-N (al-Hilu) had progressed on six framework agreement points, after a two-week pause, but disagreement remained on SPLM-N (al-Hilu)'s requirement of a secular state in South Kordofan and Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile self-determination. On 24 January on the Two Areas track, political and security agreements, constituting a framework agreement, were signed by Hemetti on behalf of the Sovereignty Council and Ahmed El Omda Badi on behalf of SPLM-N (Agar). The agreements give legislative autonomy to South Kordofan and Blue Nile; propose solutions for the sharing of land and other resources, and aim to unify all militias and government soldiers into a single unified Sudanese military body.

On 26 January, a "final" peace agreement for the northern track, including issues of studies for new dams, compensation for people displaced by existing dams, road construction and burial of electronic and nuclear waste, was signed by Shamseldin Kabashi of the Sovereignty Council and Dahab Ibrahim of the Kush Movement.[152][153][154]

In February 2020, a new unity government was announced, to govern the entire country, with the support of all sides of the conflict.[155][156] As one part of the agreement, the current cabinet was disbanded, in order to enable more opposition members to be appointed to cabinet roles.[157][158][159][160] In March 2020, negotiators and officials on both sides of the conflict attempted to work out arrangements to facilitate the appointment of civilian governors for various regions, in concert with ongoing peace efforts.[161] The EU announced its support for the peace efforts and pledged to provide financial support of 100 million Euros.[162]

The September 2021 Sudanese coup d'état attempt was a coup attempt against the Sovereignty Council of Sudan on Tuesday 21 September 2021.[163][164] According to media reports, at least 40 officers were arrested at dawn on Tuesday 21 September 2021. A government spokesman said they included "remnants of the defunct regime",[165] referring to former officials of President Omar al-Bashir's government, and members of the country's armoured corps.[166]

On 25 October 2021, the Sudanese military, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, took control of the government in a military coup. At least five senior government figures were initially detained.[167] Civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok refused to declare support for the coup and on 25 October called for popular resistance; he was moved to house arrest on 26 October. Some civilian groups including the Sudanese Professionals Association and Forces of Freedom and Change called for civil disobedience and refusal to cooperate with the coup organisers. Protests took place on 25 and 26 October against the coup and at least 10 civilians were reported as being killed and over 140 injured by the military during the first day of protests.

The junta later agreed to hand over authority to a civilian-led government, with a formal agreement scheduled to be signed on 6 April 2023.[168] However, it was delayed due to tensions between generals Burhan and Dagalo, who serve as chairman and deputy chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, respectively.[169] Chief among their political disputes is the integration of the RSF into the military.[170] One issue of contention is the RSF's insistence on a ten-year timetable for its integration into the regular army, while the regular army demands it be done in two years.[171] Other contested issues included the status given to RSF officers in the future hierarchy, and whether RSF forces should be under the command of the army chief – rather than Sudan's commander-in-chief – who is currently Burhan.[172] As a sign of their rift, Dagalo expressed regret over the October 2021 coup.[173]

On 11 April 2023, RSF forces deployed near the city of Merowe and in Khartoum.[174] Government forces ordered them to leave, but they refused, leading to clashes when RSF forces took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum.[174] On 15 April 2023, clashes broke out across Sudan, mainly in the capital city of Khartoum, between rival factions of the country's military government. The fighting began with attacks by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on key government sites. Explosions and gunfire were reported across Khartoum. As of 15 April 2023[update], both RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo and de facto leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan claimed to control key government sites, including the general military headquarters, Sudan TV headquarters, the Presidential Palace, Khartoum International Airport, and the Army chief's official residence.[171][175][176][177]

Tunisia

[edit]The 2021 Tunisian political crisis began on 25 July 2021, after Tunisian President Kais Saied dismissed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and suspended the activities of the Assembly of the Representatives of the People by invoking emergency powers from Article 80 of the Tunisian Constitution.[178] The decisions of the president were made in response to a series of protests against Ennahda, economic hardship and spike in COVID-19 cases in Tunisia. The speaker of the Tunisian parliament and leader of the Ennahda Movement Rached Ghannouchi said the president's actions were an assault on democracy and called on his supporters to take to the streets in opposition.

On 24 August, Saied extended the suspension of parliament although the constitution states the parliament can only be suspended for a month, raising concerns in some quarters about the future of democracy in the country.[179] On 22 September, President Saied issued a decree that grants him full presidential powers with the potential of the change of Tunisia's constitution, its transformation into a presidential republic and maybe even the dissolution of the parliament.[180] Earlier that day, Seifeddine Makhlouf and Fayçal Tebbini, both members of parliament were jailed.[181]

In October 2021, Saied appointed Najla Bouden Romdhane as the first female prime minister in Tunisia and the Arab world.[182] On February 6, Kais Saied dissolved the country's top independent judiciary, a move that was condemned by the opposition as a power grab.[183] On February 24, 2022, Saied announced that foreign funding for civil society organizations will be prohibited. He said, "Non-governmental organisations must be prevented from accessing external funds... and we will do that."[184]

Uganda

[edit]Unrest killed at least 45 people after the arrest of opposition leader Bobi Wine in the runup to the 2021 Ugandan general election.[185] In June 2021, four gunmen on a car opened fire against a convoy carrying Ugandan Minister of Transport Katumba Wamala, injuring him and killing his daughter and driver.[186]

Zambia

[edit]In 2020, Zambia faced sovereign default as the first sub-Saharan African country since 2005 due to economic mismanagement by the government of Edgar Lungu, who had grown public debt from 32% to 120% and scared off investment by seizing mines.[187] Debt servicing takes up four times more money from the budget than healthcare.[188] Much of the money is believed to have been lost to corruption.[188] The main opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema has been arrested.[187] The electoral roll has been nulled and only 30 days have been given for re-registration.[188] Comparisons have been drawn to neighbouring Zimbabwe.[188]

Hakainde Hichilema (born 4 June 1962) is a Zambian businessman, farmer, and politician who is the seventh and current president of Zambia since 24 August 2021.[189] After having contested five previous elections in 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015 and 2016, he won the 2021 presidential election with 59.02% of the vote.[190] He has led the United Party for National Development since 2006 following the death of the party founder Anderson Mazoka.

Zimbabwe

[edit]

The Zimbabwean dollar (sign: Z$; code: ZWL),[208] also known as the Zimdollar or Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar,[209][210] was the currency of Zimbabwe from February 2019 to April 2024. It was the only legally permitted currency for trade in Zimbabwe from June 2019 to March 2020, after which foreign currencies were legalised again.[211]

Due to the sharp depreciation of the Zimdollar, beginning almost immediately after its introduction, where possible most transactions were being done in hard currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, despite their illegality until March 2020. On 5 April 2024, it was announced that the Zimdollar would be replaced by the new Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG), a gold-backed currency, starting on 8 April.[212][213][214] On 31 August 2024, the Zimbabwean dollar (ZWL) was officially retired.[215]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ [https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/15/worst-drought-in-century-devastates-southern-africa-with-millions-at-risk Worst drought in century devastates Southern Africa, millions at risk More than 27 million lives affected by worst drought in a century, with 21 million children malnourished, says WFP], October 15, 2024, Al Jazeera.

- ^ Cheref, Abdelkader (2021-07-29). "Is Morocco's cyber espionage the last straw for Algeria?". Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Pegasus: From its own king to Algeria, the infinite reach of Morocco's intelligence services". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria blames groups it links to Morocco, Israel for wildfires". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Moroccan king reaches out again for reconciliation with Algeria | Mohamed Alaoui". AW. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa. "Algerian President: No Answer to King Mohammed VI's Dialogue Initiative". Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "President Tebboune chairs extraordinary meeting of High Security Council". Algeria Press Service. 18 August 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria accuses Morocco of involvement in its deadly fires, to "review" relations". Africanews. 2021-08-18. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria opts for escalation with Morocco amid simmering tensions |". AW. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria Accuses Morocco Of Involvement In Fires And Will Review Relations » World » Prime Time Zone". Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria breaks off diplomatic ties with neighbouring Morocco". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algiers' diplomatic break with Rabat threatens the new balance between Spain and Morocco". The Canadian. 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Morocco shuts embassy in Algiers - English Service". ANSA.it. 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Algeria closes airspace to Moroccan aviation". reuters.com. 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Burkina Faso's writer-colonel coup leader starts a new chapter in country's history". France 24. 25 January 2022. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso: Shots heard near presidential palace". BBC News. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso: Heavy gunfire heard near president's house". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso gov't denies army takeover after barracks gunfire". Al Jazeera. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso president reportedly detained by military". BBC News. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso army says it has deposed President Kabore". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso military says it has seized power". BBC News. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Who is Paul-Henri Damiba, leader of the Burkina Faso coup?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Mutinous soldiers say they detained Burkina Faso's president". AP NEWS. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Soldiers seen outside Burkina Faso state TV after mutinies". France 24. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Burkina Faso President Kaboré 'detained' by mutinous soldiers". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Soldiers say military junta now controls Burkina Faso". AP NEWS. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "ECOWAS suspends Burkina Faso over military coup". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "AU suspends Burkina Faso after coup as envoys head for talks". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso restores constitution, names coup leader president". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Chad's Idriss Deby wins 6th term as army fends off rebel advance". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ "Chad President Idriss Deby dies visiting front-line troops: Army".

- ^ "Chad's president Idriss Déby dies from combat wounds, military says". TheGuardian.com. 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Chad's president dies after clashes with rebels". 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Chad president's death: Rivals condemn 'dynastic coup'". BBC News. 21 April 2021.

- ^ "Chad's Constitution of 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ a b "Politics this week". The Economist. 2021-06-05. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ^ "Ambrose Dlamini: Eswatini's PM dies after testing positive for Covid-19". BBC News. 2020-12-14. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- ^ Why are Ethiopian leaders calling Eritrea's president ‘Hitler’?, An escalating war of words is taking place between Eritrea and Ethiopia, as the two countries face-off over a flaring border dispute that historically claimed the lives of over 100,000 people. February 27, 2020. trtworld.com.

- ^ Ethiopian cardinal, other church leaders barred from entering Eritrea, Fredrick Nzwili, CNS February 28, 2020, Catholic New Service.

- ^ UN Decries Lack of Reforms and Widespread Abuse in Eritrea, By Lisa Schlein, March 01, 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia Approves Controversial Law on Hate Speech and Disinformation". ezega.com. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ Is Ethiopia sliding backwards under Abiy Ahmed? We challenge an adviser to Ethiopia's prime minister on his record. 14 Feb 2020, al-jazeera.

- ^ How popular is Abiy Ahmed in Ethiopia as election looms?, February 27, 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Abiy faces outcry over crackdown on rebels". france24.com. 2020-02-29. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- ^ Amnesty: Ethiopian police must account for missing opposition leader, March 3, 2020.

- ^ Amnesty International Rages As Nobel Peace Prize Winner Abiy Ahmed Unleashes Police On Opposition In Oromia, Ethiopia. Vendor Killed, Musician Injured. Today News Africa

- ^ Ouloch, Fred; Karashani, Bob (2020-02-25). "Abiy's citizen-focused govt bringing more refugees home". theeastafrican.co.ke.

- ^ a b c "Ethiopia lurches towards civil war". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Tigray leader confirms bombing Eritrean capital". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Investigation reveals evidence that scores of civilians were killed in massacre in Tigray state". www.amnesty.org. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ "At least 100 killed in border clashes between Ethiopia's Somali and Afar regions - official", Reuters, 7 April 2021, retrieved 2021-04-07

- ^ Over 100 killed in clashes in Ethiopia's Afar, Somali regions, retrieved 2021-04-07

- ^ News: At Least 27 Killed in Clashes in the Border Between Afar, Somali Regions, 29 October 2020, retrieved 2020-10-29

- ^ "Protesters Block Ethiopia Rail Link After Clashes Leave 300 Dead". Bloomberg. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ "Au Gabon, Ali Bongo réélu président avec 64,27 % des voix". France 24 (in French). 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Agence France-Presse [@AFP] (30 August 2023). "#BREAKING 'We are putting an end to the current regime,' Gabon soldiers say on TV" (Tweet). Retrieved 30 August 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Gabon: après l'annonce de la réélection d'Ali Bongo, des militaires proclament l'annulation du scrutin". RFI. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Gabon: coup d'État en cours, les militaires annoncent la fin du régime". africanews. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Agence France-Presse [@AFP] (30 August 2023). "#BREAKING Gunfire heard in Gabon capital Libreville: @AFP journalists" (Tweet). Retrieved 30 August 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Guinée : quatre choses à savoir sur le référendum constitutionnel reporté qui a plongé le pays dans une nouvelle impasse politique". Franceinfo. 1 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ "Elite Guinea army unit says it has toppled president". Reuters. 5 September 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-09-05. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ "Fears of Guinea-Bissau coup attempt amid gunfire in capital". the Guardian. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Heavy gunfire heard near presidential palace in Guinea-Bissau". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Gunfire near government house in Guinea-Bissau". France 24. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau president says 'many' dead after 'failed attack against democracy'". France 24. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "An attack on American forces in Kenya raises questions and concerns". The Economist. 2020-01-11. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ a b Mohloboli, Marafaele (20 January 2020). "Lesotho 1st lady's rise to infamy". The Sowetan. Archived from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Lesotho's Thomas Thabane to be charged with murdering his wife". BBC News. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ "Libya – Crisis response", European Union.

- ^ Fadel, L. "Libya's Crisis: A Shattered Airport, Two Parliaments, Many Factions". Archived 2015-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Libya: humanitarian crisis worsening amid deepening conflict and COVID-19 threat - UNHCR

- ^ War and pandemic compound Libya’s humanitarian crisis - The Arab Weekly

- ^ Post-Gadhafi Libya: Crippled by continuous clashes, political instability - Daily Sabah

- ^ Zaptia, Sami (2020-10-23). "Immediate and permanent ceasefire agreement throughout Libya signed in Geneva". Libya Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ a b "Country Analysis Brief: Libya" (PDF). US Energy Information Administration. 19 November 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "President Obama: Libya aftermath 'worst mistake' of presidency". BBC. 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Libya — a tale of two governments, again". Arab News. 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ "Faltering international steps in Berlin towards peace in Libya". Libya Herald. 2020-01-20. Archived from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ Zaptia, Sami (2020-01-19). "The Berlin Conference on Libya: Conference Conclusions". Libya Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "UNSMIL Convenes Meeting of Libyan Economic Experts to Discuss Establishment of an Experts Commission to Unify Financial and Economic Policy and Institutions". United Nations Support Mission in Libya. 2020-01-07. Archived from the original on 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

- ^ "The 5+5 Libyan Joint Military Commission starts its meeting in Geneva today". UNSMIL. 2020-02-03. Archived from the original on 2020-02-03. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ "Transcript of press stakeout by Ghassan Salamé, Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General and head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya". UNSMIL. 2020-02-04. Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ^ Assad, Abdulkader (2020-02-26). "UNSMIL kicks off political talks in Geneva despite boycott of major Libyan lawmakers". The Libya Observer. Archived from the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (2020-03-02). "Libya peace efforts thrown further into chaos as UN envoy quits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2020-09-07. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Libya's UN-recognised government announces immediate ceasefire". Al Jazeera English. 2020-08-21. Archived from the original on 2020-08-22. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ "Statement on the HD-Organised Libyan Consultative Meeting of 7-9 September 2020 in Montreux, Switzerland". United Nations Support Mission in Libya. 2020-09-10. Archived from the original on 2020-09-11. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Libya rivals reach deal to allocate positions in key institutions". Al Jazeera English. 2020-09-11. Archived from the original on 2020-09-11. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ Zaptia, Sami (2020-09-19). "Third Libyan Economic Dialogue meeting reviews economic reform". Libya Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-09-20. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "UNSMIL Statement on the resumption of intra-Libyan political and military talks". United Nations Support Mission in Libya. 2020-10-10. Archived from the original on 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ Zaptia, Sami (2020-10-23). "Immediate and permanent ceasefire agreement throughout Libya signed in Geneva". Libya Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ "A historic day for Malawi's democracy". The Economist. 2020-02-06. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "Gunfire heard at Mali army base, warnings of possible mutiny". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ "Mali coup: Military promises elections after ousting president". BBC News. 19 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ "Possible coup underway in Mali". Deutsche Welle. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ "Mali: Gunfire heard at Kati military camp near Bamako". The Africa Report.com. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ "Mali soldiers detain senior officers in apparent mutiny". AP NEWS. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Tih, Felix (18 August 2020). "Gunshots heard at military camp near Mali capital". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ "Mali president resigns after detention by military, deepening crisis". Reuters. 19 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ "Mali President, PM Resign After Arrest, Confirming 2nd Coup in 9 Months". VOA News. 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-05-29. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ "UN calls for immediate release of Mali President Bah Ndaw". BBC News. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-05-24.

- ^ "UN mission in Mali calls for immediate release of detained president and PM". France 24. AFP. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-05-24.

- ^ Akinwotu, Emmanuel (25 May 2021). "Mali: leader of 2020 coup takes power after president's arrest". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Mali interim president says he is 'very well' after knife attack". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Saleh, Heba (15 November 2020). "Western Saharan rebels launch attacks on Moroccan troops". Financial Times. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ "Niger: Military officials who wanted to overthrow president-elect Bazoum". APA news. APA. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Soldiers arrested in Niger after 'attempted coup'". France 24. Agence France-Presse. 31 March 2021. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Niger : ce que l'on sait de la tentative de coup d'Etat en cours contre le président Mohamed Bazoum" [Niger: what we know about the ongoing coup attempt against President Mohamed Bazoum]. Franceinfo (in French). 26 July 2023. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Peter, Laurence (26 July 2023). "Niger soldiers declare coup on national TV". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "Niger's president 'held by guards' in apparent coup attempt". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "Niger general Tchiani named head of transitional government after coup". Al Jazeera. 28 July 2023. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Hairsine, Kate (2023-08-03). "Niger: How might an ECOWAS military intervention unfold?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ Asadu, Chinedu (2023-08-01). "What would West African bloc's threat to use force to restore democracy in Niger look like?". AP News. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ "ECOWAS says 'no option taken off table' as emergency summit on Niger closes". France 24. 10 August 2023. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Breaking: ECOWAS orders immediate standby force against Niger junta". Vanguard News. 10 August 2023. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "[Video] ECOWAS deploys standby force to restore constitutional order in Niger". Vanguard News. 10 August 2023. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "ECOWAS leaders say all options open in Niger, including 'use of force'". Al Jazeera. 10 August 2023. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Most of West Africa ready to join standby force in Niger: ECOWAS". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ "Mali, Burkina Faso, sends delegation to Niger in solidarity". Africanews. 8 August 2023. Archived from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Lawal, Shola (6 August 2023). "Niger coup: Divisions as ECOWAS military threat fails to play out". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Asadu, Chinedu (2024-02-24). "West Africa bloc lifts coup sanctions on Niger in a new push for dialogue to resolve tensions". AP News. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ "Peaceful protesters against Nigerian police violence are shot". The Economist. 2020-10-21. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- ^ "Somali president signs law extending mandate for two years". France 24. 2021-04-14. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ Why Somalia’s Electoral Crisis Has Tipped into Violence, 27 April 2021

- ^ "Somali premier welcomes demilitarization of capital Mogadishu". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ "Political unrest deepens in Somalia". Middle East Monitor. 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Somali capital gunfire amid election protests". BBC News. BBC. 19 February 2021.

- ^ "What is next for Somalia's political crisis?". Al Jazeera. 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Somalia's election impasse: A crisis of state building". European Council On Foreign Relations. 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Somalia's allies fear instability as political crisis deepens". Al Jazeera. 28 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Deepening Somalia crisis sparks international alarm". France 24. 28 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Hundreds of troops loyal to Somalia PM gather outside presidential palace". The National. 29 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Political unrest deepens in Somalia". Middle East Monitor. 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Somalia's leaders agree to hold delayed election by February 25". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Somalia to hold presidential election on May 15". Arab News. 5 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ "Somalia: Electoral Body Announces List of Elected Lawmakers of the Federal Parliament". allAfrica.com. 2022-04-01. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- ^ "Somalia elects new president after long overdue elections". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ AfricaNews (2022-05-16). "Somalia re-elects former leader Hassan Sheikh Mohamud as president". Africanews. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ "Somalia: UN welcomes end of fairly contested presidential election, calls for unity". UN News. 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ Perreira, Ernsie (12 July 2021). "Constitutional Court reserves judgment in Zuma case". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "Concourt Reserves Judgment in Zuma's Rescission Bid". Eyewitness News. 12 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "Judgment reserved in Zuma's rescission application". SABC. 12 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "Deaths climb to 72 in South Africa riots after Zuma jailed". CNBC. 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ Bauer, Nickolaus. "'Little to lose': Poverty and despair fuel South Africa's unrest". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ "South Africa deploys military to tackle Zuma riots". BBC. 9 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Wroughton, Lesley (12 July 2021). "South Africa deploys military as protests turn violent in wake of Jacob Zuma's jailing". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "Live Updates: Looting and violence in Gauteng and KZN". www.iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ "National Salvation Rebels Kill Six Presidential Bodyguards in South Sudan". Voice of America. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "South Sudan Kiir agrees to re-establish the 10 states - Sudan Tribune: Plural news and views on Sudan". www.sudantribune.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- ^ "Kiir agrees to relinquish controversial 32 states". Radio Tamazuj. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- ^ "South Sudan's rival leaders form coalition government". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ "More than 100 killed in South Sudan clashes". Xinhua. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ Can South Sudan's men of war lead the country to peace?, by Peter Oborne & Jan-Peter Westad, February 15, 2020. Middle East Eye website.

- ^ Sudan peace talks: Agreement on eastern track finalised, February 23 – 2020, dabangasudan website.

- ^ The trouble with South Sudan's transitional government BY AMIR IDRIS, oped, 02/28/20, thehill.com.

- ^ South Sudan Forges Unity Government, Renewing Fragile Hope For Peace February 22, 2020, by Colin Dwyer, NPR.

- ^ South Sudan's rivals form unity government meant to end war By Maura Ajak, February 22, 2020, Associated Press.

- ^ South Sudan rivals Salva Kiir and Riek Machar strike unity deal, 22 February 2020, BBC.

- ^ Unity Government Rekindles Hopes for Peace in South Sudan by Ashley Quarcoo, February 27, 2020, Carnegie Endowment website.

- ^ South Sudan's rival leaders form coalition government. Opposition leader Riek Machar was sworn in on Saturday as the deputy of President Salva Kiir. 22 Feb 2020. Al Jazeera.

- ^ Senior State Department Official On Developments in South Sudan's Peace Process, Source US State Dept. Published 26 Feb 2020.

- ^ Appointing of civilian governors, MPs remains obstacles for Sudan's peace, March 1, 2020 dabangasudan website.

- ^ European Union announces €100 million to support the democratic transition process in Sudan, February 29, 2020, EU official website.

- ^ "Sudan failed coup: Government blames pro-Bashir elements". BBC News. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "Sudanese officials say coup attempt has failed". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "تصفية اخر جيوب الانقلاب واعتقال عسكريين ومدنيين". Suna-News (in Arabic). Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "Sudanese officials say coup attempt failed, army in control". AP NEWS. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "Sudan's PM and other leaders detained in apparent coup attempt", The Guardian, Sudan, 25 October 2021, archived from the original on 2021-10-25, retrieved 2021-10-25

- ^ "Egypt calls for maximum restraint in Sudan amid military clashes". Middle East Monitor. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (15 April 2023). "Gunfire and Blasts Rock Sudan's Capital as Factions Vie for Control". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "Sudan unrest: How did we get here?". Middle East Eye. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b Salih, Zeinab Mohammed; Igunza, Emmanuel (15 April 2023). "Sudan: Army and RSF battle over key sites, leaving 56 civilians dead". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "At least 56 killed, hundreds injured in clashes across Sudan as paramilitary group claims control of presidential palace". CNN. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Olewe, Dickens (20 February 2023). "Mohamed 'Hemeti' Dagalo: Top Sudan military figure says coup was a mistake". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Sudan: clashes around the presidential palace, there are fears of a coup attempt in Khartoum – video Archived 15 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 15 April 2023.

- ^ "At least 25 killed, 183 injured in ongoing clashes across Sudan as paramilitary group claims control of presidential palace". CNN. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Mullany, Gerry (15 April 2023). "Sudan Erupts in Chaos: Who Is Battling for Control and Why It Matters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Akinwotu, Emmanuel (15 April 2023). "Gunfire and explosions erupt across Sudan's capital as military rivals clash". Lagos, Nigeria: NPR. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Tunisian lawyers, politicians split on constitutional crisis". Reuters. 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Tunisia: President extends suspension of parliament". Deutsche Welle. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Tunisia's Saied issues decree strengthening presidential powers". Al Jazeera. 22 September 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ^ "Tunisia military judge jails two members of parliament". Al Jazeera. 22 September 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ^ Mostafa Salem (29 September 2021). "Tunisia's president appoints woman as prime minister in first for Arab world". CNN. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ "Tunisia presidents steps up power grab with move against judges". the Star. 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Amara, Tarek; McDowall, Angus; Maclean, William (24 February 2022). "Tunisia's Saied will bar foreign funding for civil society". SWI swissinfo.ch. SWI swissinfo.ch. SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The Ugandan state shoots scores of citizens dead". The Economist. 2020-11-28. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ^ "Assassination attempt on Ugandan minister kills 2". Deutsche Welle. 2021-01-06. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ a b "How to stop Zambia from turning into Zimbabwe". The Economist. 2020-11-14. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ a b c d "Zambia is starting to look like Zimbabwe, the failure next door". The Economist. 2020-11-14. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ^ Foundation, Thomson Reuters. "Zambian opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema wins presidential election". news.trust.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Mfula, Chris (16 August 2021). "Zambian opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema wins landslide in presidential election". Reuters. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Mfula, Chris (18 April 2017). "Zambian opposition leader charged with trying to overthrow government". Reuters. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "Zambia: HH walks to freedom as the state enters nolle prosequi in the treason case". 16 August 2017.

- ^ "DPP drops HH case – Zambia Daily Mail".

- ^ a b "Zambia declares national disaster after drought devastates agriculture". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ "Zambia: President Hichilema Declares Drought As A National Disaster and Emergency". 2024-03-01. Retrieved 2024-04-06.

- ^ "ZAMBIA Briefing note Drought" (PDF).

- ^ "RAINFALL FORECAST 2023/2024 SEASON" (PDF).

- ^ "Fresh from a deadly cholera outbreak, Zambia declares drought a national emergency". AP News. 2024-02-29. Retrieved 2024-04-06.

- ^ Mordasov, Pavel (9 October 2019). "The Return of Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe". Mises Wire. Auburn, Alabama: Mises Institute. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019.

- ^ a b Amin, Haslinda (22 January 2020). "At More Than 500%, Zimbabwe's Ncube Sees Inflation Stabilizing". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020.

- ^ Vinga, Alois (26 January 2020). "Ncube scorned for Davos claims Zim economy recovering". New Zimbabwe. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Zimbabwe struggles with hyperinflation". New York Post. Associated Press. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019.

- ^ Sguazzin, Antony (20 April 2020). "Zimbabwe's Currency Plans Upended as It Fights on Two Fronts". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Zimbabwe's inflation soars to 131.7%". ewn.co.za. Agence France-Presse. 25 May 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ AfricaNews (2022-06-26). "Zimbabwe's annual inflation surges to 191% in June". Africanews. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ Staff Writer; Zimbabwean, The. "Zimbabwe's annual inflation surges to 191% in June". www.zawya.com. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ Mutsaka, Farai (30 April 2024). "Zimbabwe's ZiG is the world's newest currency and its latest attempt to resolve a money crisis". Yahoo Finance. Associated Press. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Zimbabwe Dollar Spot (New)(ZWL) Spot Rate". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Muronzi, Chris (3 July 2019). "Hyperinflation trauma: Zimbabweans' uneasy new dollar". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Zimbabwe struggles to keep its fledgling currency alive". The Economist. 23 May 2019.

- ^ Matiashe, Faral (15 April 2020). "Zimbabwe is on lockdown, but money-changers are still busy". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Zimbabwe launches new gold-backed currency - ZiG". 2024-04-05. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ "Zimbabwe launches 'gold-backed' currency to replace collapsing dollar". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ "Zimbabwe Replaces Battered Dollar With New Gold-Backed Currency Called ZiG". Bloomberg.com. 2024-04-05. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ "Zimbabwe changes currency code from ZWL to ZWG". The Zimbabwe Sphere. Retrieved 2024-10-08.