1989–90 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season

| 1989–90 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

|---|---|

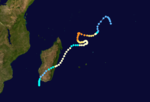

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | December 14, 1989 |

| Last system dissipated | May 21, 1990 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Walter-Gregoara |

| • Maximum winds | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 927 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total disturbances | 9 |

| Total depressions | 9 |

| Total storms | 9 |

| Tropical cyclones | 5 |

| Intense tropical cyclones | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 46 |

| Total damage | $1.5 million (1990 USD) |

| Related articles | |

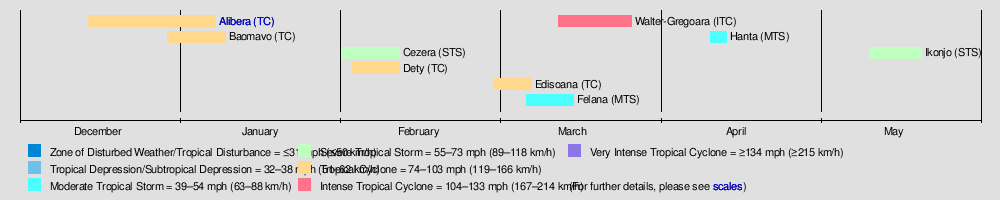

The 1989–90 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season was an average cyclone season, with nine named storms and five tropical cyclones – a storm attaining maximum sustained winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph). The season officially ran from November 1, 1989, to April 30, 1990. Storms were officially tracked by the Météo-France office (MFR) on Réunion while the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) in an unofficial basis. The first storm, Cyclone Alibera, was the second longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record in the basin, with a duration of 22 days. Alibera meandered and changed directions several times before striking southeastern Madagascar on January 1, 1989, where it was considered the worst storm since 1925. The cyclone killed 46 people and left widespread damage. Only the final storm of the year – Severe Tropical Storm Ikonjo – also had significant impact on land, when it left $1.5 million in damage (1990 USD) in the Seychelles.

Of the remaining storms, several passed near the Mascarene Islands but did not cause much impact. In early February, Severe Tropical Storm Cezera and Tropical Cyclone Dety were active at the same time and interacted with each other through the process of the Fujiwhara effect. Cyclone Gregoara was the strongest of the season, which originated as Cyclone Walter from the adjacent Australian basin. Gregoara attained peak winds of 170 km/h (110 mph) over the open waters of the Indian Ocean in March, although the JTWC considered Alibera to be stronger. In April, Moderate Tropical Storm Hanta approached the northwest coast of Madagascar, but dissipated over the Mozambique Channel.

Season summary

[edit]

During the season, the Météo-France office (MFR) on Réunion island issued warnings in tropical cyclones within the basin. Using satellite imagery from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the agency estimated intensity through the Dvorak technique, and warned on tropical cyclones in the region from the coast of Africa to 90° E, south of the equator.[1] The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), which is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force, also issued tropical cyclone warnings for the southwestern Indian Ocean.[2] The season's nine named storms and five tropical cyclones – a storm attaining maximum sustained winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph) – is the same as the long term average for the basin.[3]

Operationally, the MFR considered the tropical cyclone year to begin on August 1 and continue to July 31 of the following year.[1] However, the JTWC began the year on July 1 and it lasted through June 30 of the following year.[2] The latter agency tracked two short-lived tropical cyclones in July 1989, labeling them Tropical Cyclone 01S and 02S, but they are not considered part of MFR's season.[2] After these early storms, another tropical depression formed east of Diego Garcia on September 21, classified as Tropical Cyclone 03S.[4] Forming from the near-equatorial trough,[5] the system moved generally to the southwest, dissipating on September 27 as it approached Mauritius.[4] In the next month, Tropical Cyclone 04S formed closer to Diego Garcia on October 11. The JTWC classified it as a tropical depression on October 13 but dropped advisories the next day. The system initially drifted to the south but later turned to the northwest, dissipating on October 17.[2][6] The final of a series of early tropical systems was a tropical depression that formed east of Diego Garcia on October 28. It moved southeastward, classified by the JTWC as Tropical Cyclone 05S on October 31. The agency briefly estimated peak winds of 65 km/h (40 mph), making it a tropical storm, before the storm looped back to the west and dissipated on November 2.[2][7] Later, the precursor to Australian Tropical Cyclone Bessi was tracked in the eastern portion of the south-west Indian Ocean basin in the middle of April. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) classified the system as a minimal tropical storm while still west of 90° E, although the MFR did not classify the system before it entered the Australian basin on April 15.[8]

Systems

[edit]Tropical Cyclone Alibera

[edit]| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 16 – January 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (10-min); 954 hPa (mbar) |

The first named storm of the season, Alibera formed on December 16, well to the northeast of Madagascar. For several days, it meandered southwestward while gradually intensifying. On December 20, Alibera intensified to tropical cyclone status with 10‑minute winds of 120 km/h (75 mph), or the equivalent of a minimal hurricane. That day, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), an unofficial warning agency for the region, estimated peak 1‑minute winds of 250 km/h (160 mph), while the Météo-France office in Réunion (MFR) estimated 10‑minute winds of only 140 km/h (87 mph). After drifting erratically for several days, the storm began a steady southwest motion on December 29 as a greatly weakened system. On January 1, Alibera struck southeastern Madagascar near Mananjary, having re-intensified to just below tropical cyclone status. It weakened over land but again restrengthened upon reaching open waters on January 3. The storm shifted directions while moving generally southward, dissipating on January 5.[2][9] It was the second longest-lasting tropical cyclone in the basin since the start of satellite imagery, with a duration of 22 days. Only Cyclone Georgette in 1968 lasted longer at 24 days.[10]

Early in its duration, Alibera produced gusty winds in the Seychelles.[11] Upon moving ashore in Madagascar, the cyclone lashed coastal cities with heavy rainfall and up to 250 km/h (160 mph) wind gusts.[12] In Mananjary, nearly every building was damaged or destroyed, and locals considered it the worst storm since 1925.[13] Across the region, the cyclone destroyed large areas of crops, thousands of houses, and several roads and bridges. Alibera killed 46 people and left 55,346 people homeless. After the storm, the Malagasy government requested for international assistance.[12]

Tropical Cyclone Baomavo

[edit]| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 2 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | January 2 – January 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (95 mph) (10-min); 941 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical disturbance formed on January 2 to the northwest of the Cocos Islands,[14] which was tracked by the JTWC for the preceding few days before being classified as Tropical Cyclone 09S.[2] It originated from the monsoon trough, which is an extended low pressure area within a convergence zone.[15] It gradually intensified as it moved slowly to the southwest due to a high pressure system, or ridge, to the east.[15] On January 3, the system intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Baomavo, and two days later attained tropical cyclone status while turning more to the south. The JTWC estimated peak 1‑minute winds of 155 km/h (96 mph) on January 5, and on the next day the MFR estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 150 km/h (93 mph).[14] An approaching cold front caused Baomavo to weaken while the storm turned southeastward.[15] By January 8, the system weakened to tropical depression status while looping back to the northwest,[14] steered by a ridge to the southwest.[16] On the next day, Baomavo dissipated over the open waters of the Indian Ocean.[14]

Severe Tropical Storm Cezera

[edit]| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | January 31 – February 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

On January 31, a tropical disturbance formed just east of Agaléga. Moving southeastward, it intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Cezera on February 1,[17] the same day that the JTWC began tracking it as Tropical Cyclone 14S.[2] Cezera quickly intensified, and the JTWC upgraded it to the equivalence of a minimal hurricane on February 3 with 1‑minute peak winds of 150 km/h (93 mph). By contrast, the MFR only estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 95 km/h (59 mph).[17] By February 4, Cezera began a Fujiwhara interaction with Tropical Cyclone Dety, which was located to the east; this caused the former storm to turn back to the northwest while gradually weakening.[17][18] On February 6, the storm turned to the south and later southeast, weakening to tropical depression status that day. Cezera briefly re-intensified into a moderate tropical storm on February 7, but weakened again on the next day while passing just north of St. Brandon. After turning more to the east-northeast, the system turned sharply southward on February 10, and dissipated the next day.[17]

Tropical Cyclone Dety

[edit]| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 2 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | February 2 – February 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 135 km/h (85 mph) (10-min); 954 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical depression developed within the monsoon trough on February 2 to the southwest of Diego Garcia,[18][19] about 1,125 km (699 mi) east of Cezera.[17][19] The JTWC had been tracking the system for several days previously, classifying it as Tropical Cyclone 16S also on February 2.[2] With an anticyclone – a high pressure area over the system – providing favorable conditions,[18] the depression quickly intensified while moving generally south-southwestward. It became Moderate Tropical Storm Dety on February 3 and a tropical cyclone the next day. The MFR estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 135 km/h (84 mph), while the JTWC assessed stronger 1‑minute winds of 175 km/h (110 mph).[19] Around that time, Dety began a Fujiwhara interaction with Tropical Storm Cezera to the west, causing the former storm to turn to the east-southeast. Increased wind shear weakened the cyclone,[18] although it maintained much of its intensity through February 7 as a severe tropical storm. However, Dety quickly fell to tropical disturbance status the next day while undergoing a counterclockwise loop. After turning back to the southeast, Dety remained a weak system for several days, dissipating on February 11.[19]

Tropical Cyclone Edisoana

[edit]| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | March 1 – March 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 135 km/h (85 mph) (10-min); 954 hPa (mbar) |

The MFR began tracking a tropical disturbance on March 1 between Mauritius and Diego Garcia,[20] which was followed by the JTWC for several days previously and classified as Tropical Cyclone 18S.[2] Within a day, it intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Edisoana while tracking southwestward. On March 4, the JTWC upgraded the storm to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane, and on the next day the MFR followed suit by upgrading Edisoana to tropical cyclone status. The latter agency estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 135 km/h (84 mph), while the JTWC assessed a peak 1‑minute intensity of 185 km/h (115 mph). Around that time, the storm passed west of Rodrigues island. Edisoana accelerated southward and gradually weakened,[20] influenced by an approaching trough. On March 7, the storm began transitioning into an extratropical cyclone,[21] completing it by the next day.[20] The extratropical cyclone rapidly intensified due to the influence of the trough and a nearby ridge,[21] later being absorbed by the westerlies.[22]

Moderate Tropical Storm Felana

[edit]| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | March 7 – March 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

On March 7, a tropical depression formed in the eastern portion of the basin to the east-southeast of Diego Garcia. The nascent quickly intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Felana by March 8,[23] the same day that the JTWC began tracking it as Tropical Cyclone 22S.[2] Felana moved steadily to the southwest, although on March 10 it turned to the west-northwest, followed by another turn to the south-southwest on the next day. During this time, the MFR only estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 65 km/h (40 mph), although the JTWC assessed a peak 1‑minute intensity of 85 km/h (53 mph). Upon turning back southward, Felana passed east of Rodrigues on March 12. It weakened to tropical depression status on March 15 and dissipated the following day, having curved back to the southeast.[23]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Walter–Gregoara

[edit]| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | March 13 (entered basin) – March 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 927 hPa (mbar) |

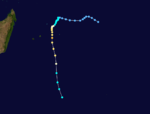

On March 4, a tropical low formed from the monsoon trough in the Australian basin southwest of the Cocos Islands. It executed a large loop and later turned back to the west due to a ridge to the south, during which it was named Walter by the BOM. On March 13, Walter crossed 90° E into the south-west Indian Ocean and was renamed Gregoara by the Mauritius Weather Service.[24][25] However, the MFR did not begin issuing advisories until March 15, when Gregoara reached 85° E.[26] The JTWC classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 23S, which was a separate number from when the storm existed in the Australian basin.[2] Gregoara moved to the southwest, intensifying into a tropical cyclone on March 16, the same day that the JTWC upgraded it to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane. On the next day, the cyclone attained peak winds – the MFR estimated 10‑minute winds of 170 km/h (110 mph), while the JTWC estimated 1‑minute winds of 205 km/h (127 mph). The storm subsequently weakened slowly, and was below tropical cyclone status by March 19. Three days later, Gregoara turned to the southeast as a weakened tropical depression,[26] subjected to cooler waters and stronger wind shear,[25] and it became extratropical.[27] For several days, the system moved slowly over the southern Indian Ocean, turning to the southwest and later to the southeast before dissipating on March 27.[26]

Moderate Tropical Storm Hanta

[edit]| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | April 11 – April 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical disturbance originated on April 11 just north of the Comoros in the Mozambique Channel.[28] Originally it only consisted of a spiral area of thunderstorms, but it gradually organized.[29] It moved southeastward and intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Hanta on April 12, passing just north of Mayotte.[28] On the next day, the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 27S with peak 1‑minute winds of 85 km/h (55 mph), although the agency did not include the name Hanta in advisories.[2] By contrast, the MFR only estimated peak 10‑minute winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). Hanta approached the northwest coast of Madagascar on April 14, passing within 11 km (6.8 mi) of the Anjajavy Forest before turning back to the west,[28] due to a ridge to the south.[29] Later that day, the system weakened and dissipated.[28]

In the Glorioso Islands north of Madagascar, Hanta produced 50 km/h (31 mph) wind gusts and 32 mm (1.3 in) of rainfall. Later, gusts reached 65 km/h (40 mph) on Mayotte, and the storm dropped 75 mm (3.0 in) of precipitation over 24 hours.[29]

Severe Tropical Storm Ikonjo

[edit]| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 11 – May 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

The final storm of the 1989-90 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season formed as a tropical disturbance on May 11 west-southwest of Diego Garcia. It moved erratically at first, initially to the west, followed by a turn to the south and later a small loop.[30] Its movement during this time and for its duration was dictated by a powerful ridge to the south.[31] During this time, the system remained weak, although it intensified into Moderate Tropical Storm Ikonjo on May 14.[30] The JTWC began classifying the storm as Tropical Cyclone 29S about two days prior.[2] After becoming a tropical storm, Ikonjo began a steadier westward movement, gradually curving back to the west-northwest, and bringing it just north of Agaléga on May 16. Two days later, the storm quickly intensified to attain peak 10‑minute winds of 95 km/h (59 mph), which made Ikonjo a severe tropical storm according to the MFR. Around that time it stalled, even drifting slightly to the west, before resuming a northwest motion,[30] influenced by a ridge to the south.[32] Ikonjo subsequently weakened while moving near or through the Outer Islands of the Seychelles. On May 21, Ikonjo dissipated at the low latitude of 5° S.[30]

Late in its duration, Ikonjo became a rare storm to affect the nation of Seychelles. It passed nearest to Desroches Island, where it destroyed much of the island's hotel. On the primary island of Mahé, Ikonje produced strong winds reaching 83 km/h (52 mph) at Seychelles International Airport, strong enough to knock over several trees. Nationwide, the storm caused $1.5 million (1990 USD) in damage and two injuries.[32] A ship passing through the center of Ikonjo reported wind gusts of 148 km/h (92 mph).[31]

See also

[edit]- Atlantic hurricane seasons: 1989, 1990

- Pacific hurricane seasons: 1989, 1990

- Pacific typhoon seasons: 1989, 1990

- North Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1989, 1990

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b Philippe Caroff; et al. (June 2011). Operational procedures of TC satellite analysis at RSMC La Reunion (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. p. iii, 183–185. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-19. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Chris Landsea; Sandy Delgado (2014-05-01). "Subject: E10) What are the average, most, and least tropical cyclones occurring in each basin?". Frequently Asked Questions. Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 HSK0390 (1989265S05085). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (September 1989). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). 8 (9). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 HSK0490 (1989284S08080). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 HSK0590 (1989302S05079). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Bessi (1990102S11092). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-01-21. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Alibera (1989349S08065). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Neal Dorst; Anne-Claire Fontan. "Sujet E6) Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". Records relatifs aux cyclones tropicaux. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Steve Newman (1989-12-23). "Earthweek: A Diary of the Planet". Moscow-Pullman Daily News. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Madagascar Cyclone January 1990 UNDRO Information Reports 1 – 2". United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs. ReliefWeb. January 1990. Retrieved 2014-10-09.

- ^ OFDA Annual Report FY 1994 (PDF) (Report). Office of United States Foreign Disaster Assistance. p. 28. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Baomavo (1989364S05095). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (January 1990). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). 9 (1). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone Baomavo, 29 December 1989 - 8 January 1990. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Global tropical/extratropical cyclone climatic atlas. 1996. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Cezera (1990032S11059). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (February 1990). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). 9 (2). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Dety (1990031S09070). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Edisoana (1990058S16075). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kyle S. Griffin; Lance F. Bosart (August 2014). "The Extratropical Transition of Tropical Cyclone Edisoana (1990)". Monthly Weather Review. 142 (8): 2772–2793. Bibcode:2014MWRv..142.2772G. doi:10.1175/MWR-D-13-00282.1.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone Edisaona, 28 February-9 March, 1990. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Global tropical/extratropical cyclone climatic atlas. 1996. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Felana (1990065S07083). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Walter" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (March 1990). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). 9 (3). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Gregoara:Walter (1990062S13091). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Tropical Depression Gregoara (ex-Walter), 15-27 March, 1990. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Global tropical/extratropical cyclone climatic atlas. 1996. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1990 Hanta (1990101S07048). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tropical Depression Hanta, 10-14 April, 1990. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Global tropical/extratropical cyclone climatic atlas. 1996. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "1990 Tropical Cyclone Ikonjo (1990130S03081)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tropical Depression Ikonjo, 11-21 May 1990. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Global tropical/extratropical cyclone climatic atlas. 1996. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Denis Chang Seng; Richard Guillande (July 2008). "Disaster risk profile of the Republic of Seychelles" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. p. 43. Retrieved 2014-10-13.