Expo 58

| 1958 Brussels | |

|---|---|

View of the exhibition's main avenue and gondola lift towards the Atomium | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | First category General Exposition |

| Name | Expo 58 |

| Area | 2 km2 (490 acres) |

| Visitors | 41,454,412 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 44 |

| Location | |

| Country | Belgium |

| City | Brussels |

| Venue | Heysel/Heizel Plateau |

| Coordinates | 50°53′50″N 4°20′21″E / 50.89722°N 4.33917°E |

| Timeline | |

| Bidding | 7 May 1948 |

| Awarded | November 1953 |

| Opening | 17 April 1958 |

| Closure | 19 October 1958 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Exposition internationale du bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince in Port-au-Prince |

| Next | Century 21 Exposition in Seattle |

| Specialized Expositions | |

| Previous | Interbau in Berlin |

| Next | Expo 61 in Turin |

| Horticultural expositions | |

| Next | Floriade 1960 in Rotterdam |

Expo 58, also known as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (French: Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles de 1958, Dutch: Brusselse Wereldtentoonstelling van 1958), was a world's fair held on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau in Brussels, Belgium, from 17 April to 19 October 1958.[1] It was the first major world's fair registered under the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) after World War II.

Background

[edit]Expo 58 was the eleventh world's fair hosted by Belgium, and the fifth in Brussels, following the fairs in 1888, 1897, 1910 and 1935. In 1953, Belgium won the bid for the next world's fair, winning out over other European capitals such as Paris and London.

Nearly 15,000 workers spent three years building the 2 km2 (490 acres) site on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north-west of central Brussels. Many of the buildings were re-used from the 1935 World's Fair, which had been held on the same site.[2]

The theme of Expo 58 was "Bilan du monde, pour un monde plus humain" (in English: "Evaluation of the world for a more humane world"), a motto inspired by faith in technical and scientific progress, as well as post-war debates over the ethical use of atomic power.[3]

The exhibition attracted some 41.5 million visitors, making Expo 58 the second largest World's Fair after the 1900 Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Paris, which had attracted 48 million visitors.[3] Every 25 years starting in 1855, Belgium had staged large national events to celebrate its national independence following the Belgian Revolution of 1830. However, the Belgian Government under Prime Minister Achille Van Acker decided to forego celebrations in 1955 to have additional funding for the 1958 Expo.[4] Since Expo 58, Belgium has not organised any more world's fairs.

Exhibition

[edit]Overview

[edit]

More than forty nations took part in Expo 58, with more than forty-five national pavilions, not including those of the Belgian Congo and Belgium itself.

The site is best known for the Atomium, a giant model of a unit cell of an iron crystal (each sphere representing an atom). During the 1958 European exposition, the molecular model hosted an observation of more than forty-one million visitors while refining an astonishment for atomism by distant global communities.[5][6] The atomistic model was opened with a call for world peace and social and economic progress, issued by King Baudouin I. The Atomium was originally foreseen to last only the six months of the exhibition; but it was never taken down, its outer coating was renewed on the 50th anniversary of the exhibition, and it stands nowadays as just as much an emblem of Brussels as the Eiffel Tower is of Paris.

Notable exhibitions include the Philips Pavilion, where "Poème électronique", commissioned specifically for the location, was played back from 425 loudspeakers, placed at specific points as designed by Iannis Xenakis, and Le Corbusier.[7]

-

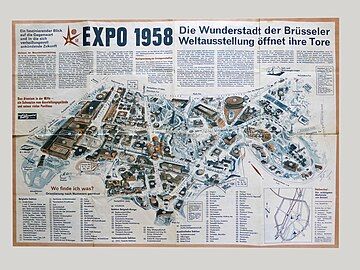

Map of Expo 58 in the Heysel/Heizel district of Brussels

-

The Philips Pavilion during Expo 58

-

The Centenary Palace served as the exhibition's entrance hall.

-

A pedestrian bridge over a model of the Belgian landscape

Belgian Congo Section

[edit]The Belgian Congo section was located in 7.7 hectares (19 acres) in close proximity to the Atomium model. The Belgian Congo, today known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was at that time a Belgian colonial holding. Expo organizers also included participants from the UN Trust Territories of Ruanda-Urundi (today, Rwanda and Burundi) in the Belgian Congo section, without differentiation.[8] This section was divided into seven pavilions: the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi Palace, agriculture; Catholic missions; insurance, banks, trade; mines and metallurgy; energy, construction, and transport; a village indigène (indigenous village). The Belgian Congo section was, above all, intended to display the "civilizing" work of the Belgian colonialism.[3] The village indigène is of the most notable modern "human zoos" of the 20th century.[9]

Human zoo

[edit]Another exhibition at the Belgian pavilion was the Congolese village that some have branded a human zoo.[10]

The Ministry of Colonies built the Congolese exhibit, intending to demonstrate their claim to have "civilized" the "primitive Africans." Native Congolese art was rejected for display, as the Ministry claimed it was "insufficiently Congolese." Instead, nearly all of the art on display was created by Europeans in a purposefully primitive and imitative style, and the entrance of the exhibit featured a bust of King Leopold II, under whose colonial rule millions of Congolese died. The 700 Congolese chosen to be exhibited by the Ministry were educated urbanites referred to by Belgians as évolués, meaning literally "evolved," but were made to dress in "primitive" clothing, and an armed guard blocked them from communicating with white Belgians who came to observe them. The exotic nature of the exhibit was lauded by visitors and international press, with the Belgian socialist newspaper Le Peuple praising the portrayal of Africans, saying it was "in complete agreement with historical truth." However, in mid-July the Congolese protested the condescending treatment they were receiving from spectators and demanded to be sent home, abruptly ending the exhibit and eliciting some sympathy from European newspapers.[3]

National pavilions

[edit]Austria

[edit]The Austrian pavilion was designed by Austrian architect Karl Schwanzer in modernist style. It was later transferred to Vienna to host the museum of the 20th century. In 2011 it was reopened under the new name 21er Haus. It included a model Austrian Kindergarten, which doubled as a day care facility for the employees, the Vienna Philharmonic playing behind glass, and a model nuclear fusion reactor that fired every 5 minutes.

Czechoslovakia

[edit]

The exposition "One Day in Czechoslovakia" was designed by Jindřich Santar who cooperated with artists Jiří Trnka, Antonín Kybal, Stanislav Libenský and Jan Kotík. Architects of the simple, but modern and graceful construction were František Cubr, Josef Hrubý and Zdeněk Pokorný. The team's artistic freedom, so rare in the hard-line communist regime of the 1950s, was ensured by the government committee for exhibitions chairman František Kahuda. He supported the famous Laterna Magika show, as well as Josef Svoboda's technically unique Polyekran. The Czechoslovak pavilion was visited by 6 million people and was officially awarded the best pavilion of the Expo 58.[11]

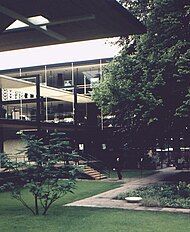

Federal Republic of Germany

[edit]

The West German pavilion was designed by the architects Egon Eiermann and Sep Ruf. The world press called it the most polished and sophisticated pavilion of the exhibition.[12]

Hungary

[edit]Hungary was represented by a large modular modernist pavilion designed by the architect Lajos Gádoros. The scenario for the exhibition was compiled by the writer Iván Boldizsár. It hosted a mix of early-1900s paintings by Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka, József Egry and Gyula Derkovitz, and modern ones such as the Life in Budapest fresco painted on aluminium panels by Túry Mária and Kádár György. In the entrance hall hung József Somogyi and Kerényi Jenő's dynamic statue group Dancers, which won a Grand Prix, and was later bought by the city of Namur. Margit Kovács' sculpture The Spinner was also on display.

The exhibition took place during very turbulent times for Hungary. The decision to participate was made in 1955, under the Stalinist party leader Mátyás Rákosi, shortly after he got rid of his reformist prime minister Imre Nagy. By the time the exhibition closed in 1958, the party leader was exiled, and the prime minister was tried and executed.[13]

Liechtenstein

[edit]The Liechtenstein pavilion featured a bronze bust of Franz Joseph II at the entrance, a collection of weapons, stamps, and important historical documents from the Principality, paintings from the Prince's personal collection, and exhibits showcasing Liechtenstein's industry, landscape, and religious history. Also featured in the building was an interior garden with a circular walkway enabling visitors to browse the entire pavilion.[14]

Mexico

[edit]The Mexican pavilion was designed by the architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. It was awarded the exposition's star of gold.

City of Paris

[edit]

The city of Paris had its own pavilion, separate from the French exhibit.

United Kingdom

[edit]

The UK pavilion was produced by the designer James Gardner, architect Howard Lobb and engineer Felix Samuely. The on-site British architect was Michael Blower, Brussels born and bilingual.[15]

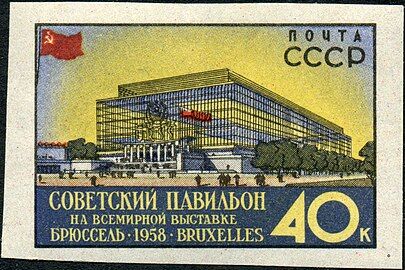

USSR

[edit]The Soviet pavilion was a large impressive building which was folded up and taken back to Russia when Expo 58 ended. There was a bookstore selling science and technology books in English and other languages published by the Moscow Press.

The exhibit featured a celestial mechanics display of the experimental Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 prototypes placed into orbit during the International Geophysical Year.[16] The robotic spacecraft was low earth orbital satellite which debuted as the Sputnik 1 on 4 October 1957 for an international spectators observation from the surface of the earth. The spacecraft completed the geocentric orbit upon depleting the silver zinc battery capacity for an atmospheric entry of the earth's atmosphere on 4 January 1958.

The exposition highlighted a model of the Soviet Union's watercraft vessel Lenin the first nuclear-powered icebreaker, and Soviet automobiles: GAZ-21 Volga, GAZ-13 Chaika, ZIL-111, Moskvitch 407 and 423, trucks GAZ-53 and MAZ-525.[17] The Soviet exposition was awarded with a Grand Prix.[17]

-

USSR pavilion

-

Interior of USSR pavilion

United States

[edit]The US pavilion was quite spacious and included a fashion show with models walking down a large spiral staircase, an electronic computer that demonstrated a knowledge of history, and a colour television studio behind glass. It also served as the concert venue for performance by the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Edward Lee Alley.[18][19] It was designed by architect Edward Durell Stone. It would also play host to the University of California Marching Band which had financed its own way to the fair under the direction of James Berdahl.[20] The United States pavilion consisted of 4 buildings,[21] one of which hosted America the Beautiful, a 360° movie attraction in Circarama made by Walt Disney Productions.[22] The film would subsequently travel to the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959,[23] and would find its first American audiences at Disneyland in Anaheim in 1960.

-

US pavilion

-

Interior of US pavilion

Yugoslavia

[edit]

The pavilion of Yugoslavia was designed by the architect Vjenceslav Richter, who originally proposed to suspend the whole structure from a giant cable-stayed mast. When that proved too complicated, Richter devised a tension column consisting of six steel arches supported by a pre-stressed cable, which stood in front of the pavilion as a visual marker and symbolized Yugoslavia's six constituent republics. Filled with modernist art, the pavilion was praised for its elegance and simplicity and Richter was awarded as Knight of the Order of the Belgian Crown. After the end of Expo 58, the pavilion was sold and reconstructed as a school in the Belgian municipality of Wevelgem, where it still stands.

Other pavilions

[edit]-

Brazilian pavilion

-

Canadian pavilion

-

Dutch pavilion

-

Japanese pavilion

-

Luxembourgish pavilion

-

Thai pavilion

-

Pavillon of Arab States

-

Vatican pavilion

-

Moroccan pavilion

Transport

[edit]

- As many visitors were expected, SABENA temporarily increased capacity by renting a couple of Lockheed Constellations.

- For the same reason, and well in time, it was decided to add a new terminal to the Melsbroek national airport; it was to be at the west side of the airport, on the grounds of the municipality of Zaventem, which has since given its name to the airport. A very modern addition was the railway station in the airport, offering direct train service to the city centre, though not to the expo itself.

- Several tram lines were built to serve the site, those to Brussels remain in service. One line (81) was temporarily deviated to go all the way through Brussels with endpoints at both ends of the Expo.

Mozart's Requiem incident

[edit]

The autograph of Mozart's Requiem was placed on display. At some point, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words "Quam olim d: C:". As of 2012[update] the perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered.[24]

International film poll

[edit]The event offered the occasion for the organization by thousands of critics and filmmakers from all over the world, of the first universal film poll in history.[25] The poll received nominations from 117 critics from 26 nations. Броненосец Потёмкин (Battleship Potemkin) received 100 votes with The Gold Rush second with 95.[26]

A jury of young filmmakers (Robert Aldrich, Satyajit Ray, Alexandre Astruc, Michael Cacoyannis, Juan Bardem, Francesco Maselli and Alexander Mackendrick) were due to select a winner from the nominees but voted not to. Instead they indicated the following as still holding value to young filmmakers: Battleship Potemkin; Grand Illusion; Mother; The Passion of Joan of Arc; The Gold Rush and Bicycle Thieves.[27]

Commemoration

[edit]- The logo for Expo 58 was designed by Lucien De Roeck, and posters based on it were produced by De Roeck and by Leo Marfurt

- The 50th anniversary of Expo 58 was selected as the main motif of a high-value collectors' coin: the Belgian €100 50th Anniversary of the International Expo in Belgium commemorative coin, minted in 2008. In the obverse, the logo of the event is depicted together with the number 50, representing its 50th anniversary.

-

Pocket sized guide to Expo 58

-

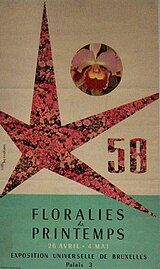

Publicity poster

-

Commemorative Belgian postage stamp

-

Commemorative US postage stamp

-

Commemorative Soviet postage stamp

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "When the world was in Brussels". Flanders Today. 16 April 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Video: Brussels World's Fair, 1958/03/17 (1958). Universal Newsreel. 1958. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d Stanard, Matthew (April 2005). "'Bilan du monde pour un monde plus déshumanisé': The 1958 Brussels World's Fair and Belgian Perceptions of the Congo". European History Quarterly. 35 (2): 267–298. doi:10.1177/0265691405051467. ISSN 0265-6914. S2CID 143002285.

- ^ Expo 58, The Royal Belgian Film Archive, Revised Edition, 2008, p. 78 (booklet accompanying DVD edition of footage from the exhibition)

- ^ Mattie, Erik (1998). Weltausstellungen (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Belser. p. 201. ISBN 9783763023585. OCLC 57604347.

- ^ "Atoms over Brussels". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 45, no. 17. Lawton, Oklahoma: Oklahoma Historical Society. The Lawton News-Review. 15 August 1957. p. 2.

- ^ Drew, Joe (16 January 2010). "Recreating the Philips Pavilion". Analog Arts. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Stanard, Matthew G. (2012). Selling the Congo: A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3988-3.

- ^ Kakissis, Joanna (26 September 2018). "Where 'Human Zoos' Once Stood, A Belgian Museum Now Faces Its Colonial Past". NPR. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Deep Racism: The Forgotten History Of Human Zoos". PopularResistance.Org. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ MF DNES, Expo 2010, Mimořádná příloha o světové výstavě v Šanghaji, 3 May 2010.

- ^ Jones, Peter Blundell; Canniffe, Eamonn (2012). Modern Architecture Through Case Studies 1945 to 1990. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-135-14409-8.

- ^ Péteri, György. “Transsystemic Fantasies: Counterrevolutionary Hungary at Brussels Expo ’58.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012, pp. 137–60. ISSN = 00220094, URL = http://www.jstor.org/stable/23248985

- ^ Official Guide to the Brussels World Exposition 1958. Tournai: Desclée & Co. 1958.

- ^ See chapter by Jonathan Woodham – Caught between Many Worlds: the British Site at Expo '58'(see bibliography)

- ^ Siegelbaum, Lewis (January 2012). "Sputnik Goes to Brussels: The Exhibition of a Soviet Technological Wonder". Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (1). Sage Publications, Ltd.: 120–136. doi:10.1177/0022009411422372. JSTOR 23248984.

- ^ a b GAZ-21I «Wołga», "Avtolegendy SSSR" Nr. 6, 2009, DeAgostini, ISSN 2071-095X (in Russian), p.7

- ^ "Choronology". 7th Army Symphony. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Pan Pipes of Sigma Alpha Iota". Annual American Music. 2: 47. 1954. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra performs at the Brussels World Fair 1958

- ^ "The Pride of California: A Cal Band Centennial Celebration". Cal Band Alumni Association.

- ^ Arke, Laurenzo (8 June 2016). "Expo 58: A Brief History of Belgium's World Fair Showcase". Culture Trip. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "America the Beautiful – 1958 Brussels World's Fair". Designing Disney. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Iwerks, Don (2019). Walt Disney's ultimate inventor : the genius of Ub Iwerks. Los Angeles: Disney Editions. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4847-4337-9. OCLC 1133108493.

- ^ Facsimile of the manuscript's last page, showing the missing corner Archived 13 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine from Austrian National Library

- ^ Władysław Jewsiewicki: "Kronika kinematografii światowej 1895–1964", Warsaw 1967, no ISBN, page 129 (in Polish)

- ^ "Inside Pictures". Variety. 24 September 1958. p. 13. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "Brussels Jury ('The Young in Heart') Can't Choose All-Time Greatest Film". Variety. 22 October 1958. p. 1. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mattie, Erik (1998). World's Fairs. New York City, New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 9781568981321. OCLC 39724144.

- Devos, Rika; De Kooning, Mil (2006). Modern Architecture - Expo 58: for a more humane world (in French). Brussels, Belgium: Dexia: Fonds Mercator. ISBN 9789061536420. OCLC 77214308.

- Pluvinage, Gonzague (2008). Expo 58: Between Utopia and Reality. Racine, Brussels: Brussels City Archives ~ State Archives in Belgium. ISBN 9782873865412. OCLC 232982985.

- Molella, Arthur P; Knowles, Scott Gabriel (2019). World's Fairs in the Cold War: Science, Technology, and the Culture of Progress. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvpbnqjx. ISBN 9780822987086. JSTOR j.ctvpbnqjx. OCLC 1119664853.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the BIE

- 1958 Brussels – approximately 160 links

- Expo '58 and a Flash-based

- A Brief History of Belgium's World's Fair Showcase

- Brussels World's Fair approaches completion, a 17 March 1958 Universal newsreel clip from the Internet Archive

- worldfairs website