1861 Confederate States presidential election in North Carolina

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

County Results[a]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1861 Confederate States presidential election in North Carolina took place on November 6, 1861, as part of the 1861 Confederate States presidential election. Unlike most Confederate states, where electors were selected by the state legislature, North Carolina selected its 12 electors through a general ticket.[3][4] Each elector on a slate represented a specific district, and the 12 elector candidates who received the highest number of votes were chosen to represent the state in the Electoral College, where they cast their votes for the president and vice president.[5]

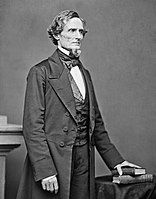

Two slates of electors were pledged to Jefferson Davis in the election, representing the two developing local factions. The "secessionist slate", led by William B. Rodman, consisted of "original secessionists" who had supported secession from early on. They were opposed by the "people's ticket", made up of former Unionists and ran with "conservative"[b] backing.[4]

The election itself was muddly with supporters of the opposite view appearing on each of the slates, including four that appeared on both slates[3] and two others that were listed partially different tickets — one of whom having withdrawn but still appeared on several tickets.[6] Nevertheless, the secessionist slate won out with its best-performing sole elector winning 27,400 votes, beating the people's ticket's 19,507.[5][6]

Background

[edit]In the aftermath of the 1860 presidential election, despite calls from Governor John Willis Ellis for secession, North Carolinians were reluctant to secede from the Union. Lawmakers in the General Assembly felt that Abraham Lincoln's victory was not a sufficient cause for secession, and the general populace believed that the Constitution would protect their rights from Lincoln's administration. When a vote was held in Februaryr 1861 on whether to call a secession convention, the proposal was rejected by voters.[7]

Despite this, both secessionist and Unionist factions remained active throughout the state, holding meetings to rally support. Governor Ellis, anticipating conflict, began organizing military training camps and preparing troops. Unionists, meanwhile, held out hope that Lincoln would avoid direct interference in the South, which they believed would lead to the Confederacy disbanding. William Woods Holden, a prominent Unionist, warned that secession could result in military occupation and the abolition of slavery, advocating for the creation of a local Constitutional Union Party. At a major Unionist meeting in Randolph County, citizens called for North Carolina to remain neutral and proposed the formation of a "Central Confederacy" of border states.[7]

Following the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for volunteer militiamen to subdue the rebellion. This action alarmed many white men and caused most Unionists to shift their stance, leading to the state withdrawing from the Union at the May 1861 secession convention.[7]

Initially, there was a brief moment of unity among the state's political leaders, but politicians quickly fractured into two camps: enthusiastic Confederates and reluctant Confederates. Early secessionist leaders, having taken control of the state government, excluded former Unionists from public offices and military positions. This exclusion caused resentment and deepened divisions among the state's leaders. Reflecting this partisan divide, early secessionists and former Unionists, such as Holden and Zebulon Vance, organized separate slates of electors for the 1861 Confederate States presidential election, despite both groups endorsing the same ticket.[7]

Results

[edit]The election itself was muddly with supporters of the opposite view appearing on each of the slates, including four that appeared on both slates[3] and two others that were listed partially different tickets — one of whom having withdrawn but still appeared on several tickets.[6] There was also an issue with the method of counting. One candidate, who appeared on both slates, represented different districts on each. When tallying the votes, Governor Henry Toole Clark combined the results from both districts, ensuring an easy victory for that candidate. While this may not have disenfranchised voters in this instance, it had the potential to do so.[5]

Ultimately, the secessionist slate prevailed, with its best-performing sole elector receiving 27,400 votes, compared to the people's ticket's 19,507.[5][6] In addition to the votes cast for the two Davis slates, there were also "many scattering votes", though the Fayetteville observer did not report a specific number.[5]

The secessionist slate won most of its votes from Breckinridge Democrats and secessionists, while the "people's ticket" won most of its votes from Douglas supporters, Bell supporters, and Unionist. The secessionist voters turned out at a higher rate than the unionists, most likely due to the excitement created by the coming of war and the fact that both tickets represented the same man. This political apathy among the Unionists possibly caused the defeat of the people's ticket.[4]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpartisan | Jefferson Davis (secessionist slate) | 27,400 | ? | |

| Nonpartisan | Jefferson Davis (people's ticket) | 19,507 | ? | |

| Scattering | ? | ? | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ The full returns of 24 counties were reported in the November 18 issue of the Fayetteville observer[1] and the return of Johnston County was reported in the November 13 issue of the Weekly state journal.[2]

- ^ Former Unionist William Woods Holden would eventually form the "Conservative" party, a political coalition of former Unionist opposed to Governor Henry Toole Clark.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Hale, Edward J. (November 28, 1861). "Fayetteville observer". Fayetteville observer. p. 3.

- ^ Spelman, John. "Weekly state journal". Weekly state journal. p. 3.

- ^ a b c McKinney, Gordon B. (2005). Zeb Vance: North Carolina's Civil War Governor and Gilded Age Political Leader. University of North Carolina Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780807875933.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Robin E. "Class Conflict and Political Upheaval: The Transformation of North Carolina Politics during the Civil War". The North Carolina Historical Review. 69 (2): 161–163 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e Hale, Edward J. (November 28, 1861). "Fayetteville observer". Fayetteville observer. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Spelman, John. "The state journal". The state journal. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Beckel, Deborah (2011). Radical Reform: Interracial Politics in Post-Emancipation North Carolina. University of Virginia Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 9780813930527.