Stephen the Great

| Stephen the Great Ștefan cel Mare | |

|---|---|

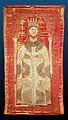

Fresco of Stephen in the Voroneț Monastery (1488) | |

| Prince of Moldavia | |

| Reign | 14 April 1457– 2 July 1504 |

| Predecessor | Peter III Aaron |

| Successor | Bogdan III the One-Eyed |

| Born | 9 or 16 January 1433–1440 |

| Died | 2 July 1504 Suceava |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Mărușca (?) Evdochia of Kiev Maria of Mangup Maria Voichița of Wallachia |

| Issue more... | Alexandru Bogdan III Petru Rareș |

| Dynasty | Mușat |

| Father | Bogdan II of Moldavia |

| Mother | Maria Oltea |

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox |

| Military career | |

| Service | Moldavian military forces |

| Battles / wars | |

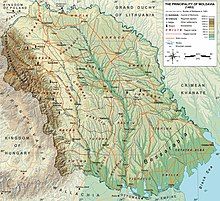

Stephen III, commonly known as Stephen the Great (Romanian: Ștefan cel Mare; pronunciation: [ˈʃtefan tʃel ˈmare]); died 2 July 1504), was Voivode (or Prince) of Moldavia from 1457 to 1504. He was the son of and co-ruler with Bogdan II, who was murdered in 1451 in a conspiracy organized by his brother and Stephen's uncle Peter III Aaron, who took the throne. Stephen fled to Hungary, and later to Wallachia; with the support of Vlad III Țepeș, Voivode of Wallachia, he returned to Moldavia, forcing Aaron to seek refuge in Poland in the summer of 1457. Teoctist I, Metropolitan of Moldavia, anointed Stephen prince. He attacked Poland and prevented Casimir IV Jagiellon, King of Poland, from supporting Peter Aaron, but eventually acknowledged Casimir's suzerainty in 1459.

Stephen decided to recapture Chilia (now Kiliia in Ukraine), an important port on the Danube, which brought him into conflict with Hungary and Wallachia. He besieged the town during the Ottoman invasion of Wallachia in 1462, but was seriously wounded during the siege. Two years later, he captured the town. He promised support to the leaders of the Three Nations of Transylvania against Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, in 1467. Corvinus invaded Moldavia, but Stephen defeated him in the Battle of Baia. Peter Aaron attacked Moldavia with Hungarian support in December 1470, but was also defeated by Stephen and executed, along with the Moldavian boyars who still endorsed him. Stephen restored old fortresses and built new ones, which improved Moldavia's defence system as well as strengthened central administration. Ottoman expansion threatened Moldavian ports in the region of the Black Sea. In 1473, Stephen stopped paying tribute (haraç) to the Ottoman sultan and launched a series of campaigns against Wallachia in order to replace its rulers – who had accepted Ottoman suzerainty – with his protégés. However, each prince who seized the throne with Stephen's support was soon forced to pay homage to the sultan.

Stephen eventually defeated a large Ottoman army in the Battle of Vaslui in 1475. He was referred to as Athleta Christi ("Champion of Christ") by Pope Sixtus IV, even though Moldavia's hopes for military support went unfulfilled. The following year, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II routed Stephen in the Battle of Valea Albă, but the lack of provisions and the outbreak of a plague forced him to withdraw from Moldavia. Taking advantage of a truce with Matthias Corvinus, the Ottomans captured Chilia and their Crimean Tatar allies Cetatea Albă (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in Ukraine) in 1484. Although Corvinus granted two Transylvanian estates to Stephen, the Moldavian prince paid homage to Casimir, who promised to support him to regain Chilia and Cetatea Albă. Stephen's efforts to capture the two ports ended in failure. From 1486, he again paid a yearly tribute to the Ottomans. During the following years, dozens of stone churches and monasteries were built in Moldavia, which contributed to the development of a specific Moldavian architecture.

Casimir IV's successor, John I Albert, wanted to grant Moldavia to his younger brother, Sigismund, but Stephen's diplomacy prevented him from invading Moldavia for years. John Albert attacked Moldavia in 1497, but Stephen and his Hungarian and Ottoman allies routed the Polish army in the Battle of the Cosmin Forest. Stephen again tried to recapture Chilia and Cetatea Albă, but he had to acknowledge the loss of the two ports to the Ottomans in 1503. During his last years, his son and co-ruler Bogdan III played an active role in government. Stephen's long rule represented a period of stability in the history of Moldavia. From the 16th century onwards both his subjects and foreigners remembered him as a great ruler. Modern Romanians regard him as one of their greatest national heroes, and he also endures as a cult figure in Moldovenism. After the Romanian Orthodox Church canonized him in 1992, he is venerated as "Stephen the Great and Holy" (Ștefan cel Mare și Sfânt).

Early life

[edit]

Stephen was the son of Bogdan, who was a son of Alexander the Good, Prince of Moldavia.[1] Stephen's mother, Maria Oltea,[1][2][3] was most probably related to the princes of Wallachia, according to historian Radu Florescu.[4] The date of Stephen's birth is unknown,[5][6] though historians estimate that he was born between 1433 and 1440.[7][8] One church diptych records that he had five siblings: brothers Ioachim, Ioan, Christea; and sisters Sorea and Maria.[2][9] Some of Stephen's biographers hypothesize that Cârstea Arbore, father of the statesman Luca Arbore, was the prince's fourth brother, or that Cârstea was the same as Ioachim.[10] These links with the high-ranking Moldavian boyars are known to have been preserved through matrimonial connections: Maria, who died in 1485, was the wife of Șendrea, gatekeeper of Suceava; Stephen's other brother-in-law, Isaia, also held high office at his court.[11][12]

The death of Alexander the Good in 1432 gave rise to a succession crisis that lasted more than two decades.[13][14] Stephen's father seized the throne in 1449 after defeating one of his relatives with the support of John Hunyadi, Regent-Governor of Hungary.[13][15] Stephen was styled voivode in his father's charters, showing that he had been made his father's heir and co-ruler.[5][16][17] Bogdan acknowledged the suzerainty of Hunyadi in 1450.[18] Stephen fled to Hungary after Peter III Aaron (who was also Alexander the Good's son) murdered Bogdan in October 1451.[5][4][19][20]

Vlad Țepeș (who had lived in Moldavia during Bogdan II's reign) invaded Wallachia and seized the throne with the support of Hunyadi in 1456.[21] Stephen either accompanied Vlad to Wallachia during the military campaign or joined him after Vlad became the ruler of Wallachia.[22] According to reports from the 1480s, Stephen spent part of that interval in Brăila, where he fathered an illegitimate son, Mircea.[23] With the assistance of Vlad, Stephen stormed into Moldavia at the head of an army 6,000 strong in the spring of 1457.[5][24][25][26] According to Moldavian chronicles, "men from the Lower Country" (the southern region of Moldavia) joined him.[5][24][27] The 17th-century Grigore Ureche wrote: "Stephen routed Peter Aaron at Doljești on 12 April, but Peter Aaron left Moldavia for Poland only after Stephen inflicted a second defeat on him at Orbic."[20][24][25]

Reign

[edit]Early campaigns

[edit]One widely accepted theory, based on Ureche, states that an assembly of boyars and Orthodox clergymen acclaimed Stephen the ruler of Moldavia at Direptate, a meadow near Suceava. According to scholar Constantin Rezachievici, this elective custom has no precedent before the 17th century, and appears superfluous in Stephen's case; he argues that it was a legend fabricated by Ureche.[28] While this election remains uncertain, various historians agree that Teoctist I, Metropolitan of Moldavia, anointed Stephen prince.[29][30][31][32] To emphasize the sacred nature of his rule, Stephen styled himself "By the Grace of God, ... Stephen voivode, lord (or hospodar) of the Moldavian lands" on 13 September 1457.[33] His use of Christian devices for legitimization overlapped with a troubled context for Moldavian Orthodoxy: the attempted Catholic–Orthodox union had divided the Byzantine Rite churches into supporters and dissidents; likewise, the Fall of Constantinople had encouraged local bishops to consider themselves independent of the Patriarchy. There is a long-standing dispute about whether Teoctist was a dissenter, belonging to one of the several emancipated Orthodox jurisdictions, or a loyalist of Patriarch Isidore.[34] Historian Dan Ioan Mureșan argues that the evidence is for the latter option, because Moldavia appears on the list of Patriarchate jurisdictions, and because Stephen, though he tested the Patriarch by sometimes using imperial titles such as tsar by 1473, was never threatened with excommunication.[35]

As one of his earliest actions as prince, Stephen attacked Poland to prevent Casimir IV from supporting Peter Aaron in 1458.[29][36] This first military campaign "established his credentials as a military commander of stature", according to historian Jonathan Eagles.[37] However, he wanted to avoid prolonged conflict with Poland, because the recapture of Chilia was his principal aim.[38] Chilia was an important port on the Danube that Peter III of Moldavia had surrendered to Hungary in 1448.[29][39] He signed a treaty with Poland on the river Dniester on 4 April 1459.[29][38][40] He acknowledged the suzerainty of Casimir IV and promised to support Poland against Tatar marauders.[29][40] Casimir in turn pledged to protect Stephen against his enemies and to forbid Peter Aaron from returning to Moldavia.[29][40][41] Peter Aaron subsequently left Poland for Hungary and settled in Székely Land, Transylvania.[29][31]

Stephen invaded Székely Land multiple times in 1461.[29][40] Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, decided to support Peter Aaron, giving him shelter in his capital at Buda.[40] In 1462, Stephen underscored his wish for good relations with the Ottoman Empire, expelling from Moldavia the Franciscans, who were agitating for a united church and a crusade.[42] Stephen continued to pay the yearly tribute to the Ottoman Empire initiated by his predecessor.[31][38][42] He also made a new agreement with Poland in Suceava on 2 March 1462, promising to personally swear fealty to Casimir IV if the king required it.[43] This treaty declared that Casimir was the sole suzerain of Moldavia, prohibiting Stephen from alienating Moldavian territories without his authorization.[44][45] It also obliged Stephen to recapture the Moldavian territories that had been lost, obviously in reference to Chilia.[44][45]

Written sources evidence that the relationship between Stephen and Vlad Țepeș became tense in early 1462.[46] On 2 April 1462, the Genoese governor of Caffa (now Feodosia in Crimea) informed Casimir IV of Poland that Stephen had attacked Wallachia while Vlad Țepeș was waging war against the Ottomans.[47] The Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II, later invaded Wallachia in June 1462.[48] Mehmed's secretary, Tursun Beg, recorded that Vlad Țepeș had to station 7,000 soldiers near the Wallachian-Moldavian frontier during the sultan's invasion to "protect his country against his Moldavian enemies".[49] Both Tursun and Laonikos Chalkokondyles note that Stephen's troops were loyal to Mehmed, and directly involved in the invasion.[42] Taking advantage of the presence of the Ottoman fleet at the Danube Delta, Stephen also laid siege to Chilia in late June.[49][50] According to Domenico Balbi, the Venetian envoy in Istanbul, Stephen and the Ottomans besieged the fortress for eight days, but they could not capture it, because the "Hungarian garrison and Țepeș's 7,000 men" defeated them, killing "many Turks".[49][51] Stephen was seriously wounded during the siege, suffering an injury on his left calf, or his left foot, that would never heal his entire life.[29][51]

Consolidation

[edit]Stephen again laid siege to Chilia on 24 January 1465.[40][52][3] The Moldavian army bombarded the fortress for two days, forcing the garrison to surrender on 25 or 26 January.[52][3] The sultan's vassal, Radu the Handsome, Voivode of Wallachia, had also laid claim to Chilia, thus the capture of the port gave rise to conflicts not only with Hungary, but also with Wallachia and the Ottoman Empire.[53][54][55] In 1465[40] or earlier,[56] Stephen peacefully regained the fortress of Hotin (now Khotyn in Ukraine) on the Dniester from the Poles. To commemorate the capture of Chilia, Stephen ordered the construction of the Church of the Assumption of the Mother of God in a glade on the Putna River in 1466.[57] It became the central monument of Putna Monastery, extended by Stephen in 1467, when he donated the village of Vicov, and finally consecrated in September 1470.[58]

At Matthias Corvinus' instance, the Diet of Hungary abolished all previous exemptions relating to the tax known as the "chamber's profit".[59] The leaders of the Three Nations of Transylvania who regarded the reform as an infringement of their privileges declared on 18 August 1467 that they were ready to fight to defend their liberties.[59] Stephen promised support to them,[40] but they yielded to Corvinus without resistance after the king marched to Transylvania.[60] Corvinus invaded Moldavia and captured Baia, Bacău, Roman and Târgu Neamț.[40] Stephen assembled his army and launched a crushing defeat on the invaders in the Battle of Baia on 15 December.[3][61][62] This episode was presented in contemporary Hungarian chronicles as a defeat of Stephen's armies.[63] However, Corvinus, who received wounds in the battle, could only escape from the battlefield with the help of Moldavian boyars who had joined him.[3][64] A group of boyars rose up against Stephen in the Lower Country,[65] but he had 20 boyars and 40 other landowners captured and executed before the end of the year.[64]

Stephen again swore loyalty to Casimir IV in the presence of the Polish envoy in Suceava on 28 July 1468.[45] He conducted raids against Transylvania between 1468 and 1471.[64] When Casimir came to Lviv in February 1469 to personally receive his homage, Stephen did not go to meet him.[66] In the same year or in early 1470, Tatars invaded Moldavia, but Stephen routed them in the Battle of Lipnic near the Dniester.[64][67][68] To strengthen the defence system along the river, Stephen decided to erect new fortresses at Old Orhei and Soroca around the same time.[68][69] A Wallachian army laid siege to Chilia, but it could not force the Moldavian garrison to surrender.[64]

Matthias Corvinus sent peace proposals to Stephen.[66] His envoys sought Casimir IV's advice on Corvinus' proposals at the Sejm (or general assembly) of Poland at Piotrków Trybunalski in late 1469.[66] Stephen invaded Wallachia and destroyed Brăila and Târgul de Floci (the two most important Wallachian centres of commerce on the Danube) in February 1470.[64][67][70][71] Peter Aaron hired Székely troops and broke into Moldavia in December 1470,[64] but his attack was probably anticipated by Stephen.[72] The voivode defeated his rival near Târgu Neamț.[64] Peter Aaron fell captive in the battlefield. He and his Moldavian supporters, among them Stephen's vornic and brother-in-law, Isaia,[12] and the chancellor Alexa, were executed on the orders of Stephen.[67][64][73] Radu the Fair also invaded Moldavia, but Stephen defeated him at Soci on 7 March 1471.[64][70] Reportedly, he killed all but two of the Wallachian noblemen he captured in battle.[74]

The relationship between Casimir IV and Matthias Corvinus became tense in early 1471.[75] After Stephen failed to support Poland, Casimir IV dispatched an embassy to Moldavia, insisting that Stephen should comply with his obligations.[66][76] Stephen met the Polish envoys in Vaslui on 13 July, reminding them of the hostile acts Polish noblemen committed along the border and demanded the extradition of the Moldavian boyars who had fled to Poland.[66] In parallel, he sent his own envoys to Hungary to start negotiations with Corvinus.[66] He granted commercial privileges to Saxon merchants from the Transylvanian town of Corona (now Brașov) on 3 January 1472.[67][77]

Wars with Mehmed II

[edit]The Ottomans put pressure on Stephen to abandon Chilia and Cetatea Albă (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in Ukraine) in the early 1470s.[78] Instead of obeying their demands, Stephen declined to send the yearly tribute to the Sublime Porte in 1473.[64][78][79] From 1472, he had friendly contacts with Uzun Hasan, sultan of Aq Qoyunlu, plotting an anti-Ottoman coordination.[67] Taking advantage of Mehmed's war against Uzun in Anatolia, Stephen invaded Wallachia to replace Radu the Fair, an Ottoman-installed Muslim convert and vassal, with his protégé, Basarab III Laiotă.[80] He routed the Wallachian army at Râmnicu Sărat in a battle that lasted for three days from 18 to 20 November 1473.[79][80] Four days later, the Moldavian army captured Bucharest and Stephen placed Basarab on the throne.[79][80] However, Radu regained Wallachia with Ottoman support before the end of the year.[64] Basarab again expelled Radu from Wallachia in 1475, but the Ottomans once more assisted him to return.[79][81] The Wallachians took revenge by plundering some parts of Moldavia.[79] To restore Basarab, Stephen launched a new campaign to Wallachia in October, forcing Radu to flee from the principality.[79][81]

Mehmed II ordered Hadım Suleiman Pasha, Beylerbey (or governor) of Rumelia, to invade Moldavia – an Ottoman army of about 120,000 strong broke into Moldavia in late 1475.[82] Wallachian troops also joined the Ottomans, while Stephen received support from Poland and Hungary.[81][83] Outnumbered three to one by the invaders, Stephen was forced to retreat.[82][84] He joined battle with Hadım Suleiman Pasha at Podul Înalt (or the High Bridge) near Vaslui on 10 January 1475.[79][82][85] Before the battle, he had sent his buglers to hide behind the enemy fronts.[82] When they suddenly sounded their horns, they caused such a panic among the invaders that they fled from the battlefield.[82] Over the next three days, hundreds of Ottoman soldiers were massacred and the survivors retreated from Moldavia.[79][74][82]

Stephen's victory in the Battle of Vaslui was "arguably one of the biggest European victories over the Ottomans", according to historian Alexander Mikaberidze.[82] Mara Branković, Mehmed II's stepmother, stated the Ottomans "had never suffered a greater defeat".[79] Stephen sent letters to the European rulers to seek their support against the Ottomans, reminding them that Moldavia was "the Gateway of Christianity" and "the bastion of Hungary and Poland and the guardian of these kingdoms".[81][84][86] Pope Sixtus IV praised him as Verus christiane fidei athleta ("The true defender of the Christian faith").[86] However, neither the Pope, nor any other European power, sent material support to Moldavia.[81][84] Stephen was also approaching Mehmed with peace offers. According to disputed reports by the chronicler Jan Długosz, he was also playing down the invasion as the deed of "some fugitives and brigands" whom the Sultan would want to punish.[87]

Meanwhile, Stephen's brother-in-law, Alexander, seized the Principality of Theodoro in the Crimea at the head of a Moldavian army.[88][89] Stephen also decided to expel his former protégé, Basarab Laiotă, from Wallachia, because Basarab had supported the Ottomans during their invasion of Moldavia.[90] He made an alliance with Matthias Corvinus in July,[79][89] persuading him to release Basarab's rival, Vlad Țepeș, who had been imprisoned in Hungary in 1462.[90] Stephen and Vlad made an agreement to put an end to the conflicts between Moldavia and Wallachia, but Corvinus did not support them to invade Wallachia.[90] The Ottomans occupied the Principality of Theodoro and the Genoese colonies in the Crimea before the end of 1475.[79][88] Stephen ordered the execution of the Ottoman prisoners in Moldavia to take vengeance for the massacre of Alexander of Theodoro and his Moldavian retainers.[88] Thereafter the Venetians, who had waged war against the Ottomans since 1463, regarded Stephen as their principal ally.[91] With their support, Stephen's envoys tried to persuade the Holy See to finance Stephen's war directly, instead of sending the funds to Matthias Corvinus.[92] The Signoria of Venice emphasized, "No one should fail to understand the extent to which Stephen could influence the evolution of events, one way or another", referring to his pre-eminent role in the anti-Ottoman alliance.[92]

Mehmed II personally commanded a new invasion against Moldavia in the summer of 1476.[79][78][84] This force included 12,000 Wallachians under Laiotă, and a retinue of Moldavians under a certain Alexandru, who claimed to be Stephen's brother.[79] The Crimean Tatars were the first to break into Moldavia at the Sultan's order, but Stephen routed them.[83][93][94] He also persuaded the Tatars of the Great Horde to break into the Crimea, forcing the Crimean Tatars to withdraw from Moldavia.[93] The Sultan invaded Moldavia in late June 1476.[83][93][95]

Himself supported by troops sent by Corvinus,[95] Stephen adopted a scorched earth policy, but could not avoid a pitched battle.[83] He suffered a defeat in the Battle of Valea Albă at Războieni on 26 July and had to seek refuge in Poland, but the Ottomans could not capture the fortress of Suceava, and similarly failed before Neamț.[81][95][94] The lack of sufficient provisions and an outbreak of cholera in the Ottoman camp forced Mehmed to leave Moldavia, enabling the voivode to return from Poland.[81][96] Folk tradition claims that Stephen had also been pledged a new army with the free peasantry of Putna County, grouped around the seven sons of a local lady, Tudora "Baba" Vrâncioaia. This contingent reportedly attacked the Ottomans' flank at Odobești.[97][98] Another account, repeated by Ureche, is that Maria Oltea forced her son back into battle, pushing him to either return victorious or die.[99]

The Byzantine historian George Sphrantzes concluded that Mehmed II "had suffered more defeats than victories" during the invasion of Moldavia.[100] From summer 1475, during an interlude in the rivalry between Poland and Hungary, Stephen swore his allegiance to the latter.[101] With Hungarian support, Stephen and Vlad Țepeș invaded Wallachia, forcing Basarab Laiotă to flee in November 1476.[94][100] Stephen returned to Moldavia, leaving Moldavian troops behind for Vlad's protection.[102] The Ottomans invaded Wallachia to restore Basarab Laiotă.[94][103] Țepeș and his Moldavian retainers were massacred before 10 January 1477.[103] Stephen again broke into Wallachia and replaced Basarab Laiotă with Basarab IV the Younger.[94][81]

Stephen sent his envoys to Rome and Venice, including John Tsamblak, to persuade the Christian powers to continue the war against the Ottomans.[94][104] He and Venice also wanted to involve the Great Horde in the anti-Ottoman coalition, but the Poles were unwilling to allow the Tatars to cross their territories.[104] To strengthen his international position, Stephen signed a new treaty with Poland on 22 January 1479, promising to personally swear fealty to Casimir IV in Colomea (now Kolomyia in Ukraine) if the king specifically demanded it.[105] Venice and the Ottoman Empire made peace in the same month; Hungary and Poland in April.[105] After Basarab the Younger paid homage to the sultan, Stephen had to seek reconciliation with the Ottomans.[105] In May 1480, he promised to renew the annual tribute that he had stopped paying in 1473.[105] Taking advantage of the peace, Stephen made preparations to a new confrontation with the Ottoman Empire.[105] He again invaded Wallachia and replaced Basarab the Younger with one Mircea, possibly Stephen's own son,[106] but Basarab regained Wallachia with Ottoman support.[94][107] The Wallachians and their Ottoman allies broke into Moldavia in the spring of 1481.[107]

Wars with Bayezid II

[edit]Mehmed II died in 1481.[108] The conflict between his two sons, Bayezid II and Cem, enabled Stephen to break into Wallachia and the Ottoman Empire in June.[109] He routed Basarab the Younger at Râmnicu Vâlcea and placed Vlad Țepeș's half-brother,[110] Vlad Călugărul (Vlad the Monk), on the throne.[111][107][112] After Basarab the Younger returned with Ottoman support, Stephen made a last attempt to secure his influence in Wallachia.[107] He again led his army to Wallachia and defeated Basarab the Younger, who died in the battle.[107] Although Vlad Călugărul was restored, he was soon forced to accept the Sultan's suzerainty.[107] Anticipating a new Ottoman attack, Stephen fortified his frontier with Wallachia and entered an alliance with Ivan III of Russia, Grand Prince of Moscow.[113]

...since [Stephen the Great] has ruled in Moldavia he has not liked any ruler of Wallachia. He did not wish to live with [Radu the Fair], nor with [Basarab Laiotă], nor with me. I do not know who can live with him.

Matthias Corvinus signed a five-year truce with Bayezid II in October 1483.[101][115][116] The truce applied to all Moldavia, with the exception of the ports.[107] Bayezid invaded Moldavia and captured Chilia on 14 or 15 July 1484.[117][118][113] His vassal, Meñli I Giray, also broke into Moldavia and seized Cetatea Albă on 3 August.[117][118] The capture of the two ports secured the Ottomans' control of the Black Sea.[95][117][119] Bayezid left Moldavia only after Stephen personally came to pay homage to him.[117] Although this prostration was largely without effect on Moldavian independence,[120] the loss of Chilia and Cetatea Albă put an end to the Moldavian control of important trading routes.[121]

Corvinus was unwilling to break his own truce with Bayezid, having tacit Ottoman backing for his own war in the west.[122] However, he granted his vassal a territorial gift in Transylvania, comprising the domains of Ciceu and Cetatea de Baltă. According to various interpretations, this exchange occurred in or after 1484, and was meant to compensate Stephen for the loss of his ports.[105][107][123][124] Medievalist Marius Diaconescu dates the lease of Cetatea to 1482, when Corvinus agreed to give Stephen a place of refuge, should Moldavia fall to the Ottomans, while Ciceu only became Stephen's castle in 1489.[125] Both citadels were on land confiscated after conflicts between the Three Nations and Corvinus. Ciceu had been a fief of the Losonczi family, under litigation, while Cetatea had been a special domain of the Voivode of Transylvania, whose last titular owner before Stephen was John Pongrác of Dengeleg.[126]

By then, war between the Poles and the Ottomans was in preparation, with clashes between the two sides occurring in 1484.[119] Historian Șerban Papacostea notes that Casimir IV had always remained neutral during Stephen's conflicts with the Ottomans, but the Ottoman control of the mouths of the Dnieper and the Danube threatened Poland. The king, Papacostea argues, also wanted to strengthen his suzerainty over Moldavia, which helped him decide to intervene in the conflict on Stephen's behalf.[127] Casimir formed[119] or joined with[128] an anti-Ottoman league, which, in 1485, had also gathered reluctant support from the Teutonic Knights.[129] Historians provide different readings of the issue: according to Robert Nisbet Bain, Casimir's intervention also drove the Ottomans out of Moldavia;[128] Veniamin Ciobanu however argues that the Polish involvement[when?] remained non-military, purely diplomatic.[130]

Casimir then marched on Colomea with 20,000 troops.[119][128][131] To secure his support, Stephen also went to Colomea and swore fealty to him on 12 September 1485.[127][132][133][130][134] The ceremony took place in a tent, but its curtains were drawn aside at the moment when Stephen was on his knees before Casimir.[135] Three days after Stephen's oath of fealty, Casimir IV pledged that he would not acknowledge the capture of Chilia and Cetatea Albă by the Ottomans without Stephen's consent.[136] During Stephen's visit in Poland, the Ottomans broke into Moldavia and sacked Suceava.[137][113] They also tried to place a pretender, Peter Hronoda, on the throne.[113][135][138][139]

Stephen returned from Poland and defeated the invaders with Polish assistance at Cătlăbuga Lake in November.[113][118][140][141] He again confronted the Ottomans at Șcheia in March 1486, but could not recapture Chilia and Cetatea Albă.[113][140] He narrowly escaped with his life, reportedly after being helped by the Aprod Purice, whom tradition identifies as patriarch of the Movilești family.[142] Historian Vasile Mărculeț agrees with Ottoman sources in noting that Șcheia was not a military victory for Moldavia, but overall a relative success for his enemy, Skender Pasha. Moldavians reported winning the day only because they narrowly avoided disaster; and because Hronoda, recognized a voivode by dissenting boyars, was captured and beheaded.[139] In the end, Stephen signed a three-year truce with the Porte, promising to pay the yearly tribute to the Sultan.[113][132][137][143][144]

Conflicts with Poland

[edit]

Researcher V. J. Parry argues that, because the Poles were continuously harassed by the Great Horde, they were in no position to help Stephen.[118] Eventually, in late 1486, Poland announced plans of actually starting a "crusade" against the Ottomans, to be led by John Albert; Stephen approached the Sejm to negotiate Moldavia's role in the affair.[145] He kept out, with the expedition being rerouted from Lviv, then attacking the Tatars.[146] Poland concluded a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire in 1489, acknowledging the loss of Chilia and Cetatea Albă, without Stephen's consent.[147][148] Although the treaty confirmed Moldavia's frontiers, Stephen regarded it as a breach of his 1485 agreement with Casimir IV.[147][137] Instead of accepting the treaty, he acknowledged the suzerainty of Matthias Corvinus.[123][137][148] However, Corvinus died unexpectedly on 6 April 1490.[148][149][150] Four candidates laid claim to Hungary, including Maximilian of Habsburg, and Casimir IV's two sons, John Albert and Vladislaus.[148][151]

Stephen supported Maximilian of Habsburg, who urged the Three Nations of Transylvania to cooperate with Stephen against his opponents.[104][152] Most Hungarian lords and prelates, however, supported Vladislaus who was crowned king on 21 September, forcing Maximilian to withdraw from Hungary in November.[153] For John Albert (who was his father's heir in Poland) did not abandon his claim,[154] Stephen decided to support Vladislaus in order to prevent a personal union between Hungary and Poland.[137][155] He broke into Poland and captured Pocuția (now Pokuttya in Ukraine).[148][152][155] He believed that he was entitled to this former Moldavian fief, its revenue redirected toward paying the Ottoman tribute.[148] Stephen also supported Vladislaus against the Ottomans[137][156] who broke into Hungary several times after Corvinus' death.[157] In exchange, Vladislaus confirmed Stephen's claim to Ciceu and Cetatea de Baltă in Transylvania.[158][159] John Albert, in turn, was forced to acknowledge his brother as the lawful king in late 1491.[137]

Casimir IV died on 7 June 1492.[160] One of his younger sons, Alexander, succeeded him in Lithuania, and John Albert was elected king of Poland in late August.[160] Ivan III of Moscow broke into Lithuania to expand his authority over the principalities along the borderlands.[161] During the following years, Ivan and Stephen coordinated their diplomacy, which enabled Ivan to persuade Alexander to acknowledge the loss of significant territories to Moscow in February 1494.[162][163]

Ottoman pressure also brought about a rapprochement between Hungary and Poland.[137][164] Vladislaus met his four brothers, including John Albert and Sigismund, in Lőcse (now Levoča in Slovakia) in April 1494.[158][165] They planned a crusade against the Ottoman Empire.[165] However, John Albert wanted to strengthen Polish suzerainty over Moldavia and to dethrone Stephen in favour of Sigismund, which gave rise to new tensions between Poland and Hungary.[166][167] Shortly after the conference, John Albert decided to launch a campaign against the Ottomans to recapture Chilia and Cetatea Albă.[162][166][168] Fearing that the subjugation of Moldavia was John Albert's actual purpose, Stephen made several attempts to prevent his campaign.[119][169][170][171] With Ivan III's support, he persuaded Alexander of Lithuania not to associate himself with John Albert.[169][172] As reported by the Bychowiec Chronicle, the Lithuanian magnates also condemned the war, and simply refused to cross the Southern Bug.[173]

For its part, the Polish army marched across the Dniester into Moldavia in August 1497.[174][175] The Sultan sent 500 or 600 Janissaries to Moldavia at Stephen's request,[174][176] joining the Moldavian forces gathered at Roman.[175] Stephen sent his chancellor, Isaac, to John Albert, requesting the withdrawal of Polish forces from Moldavia, but John Albert had Isaac imprisoned.[174][175] The Poles then laid siege to Suceava on 24 September.[168][175][177] The campaign failed: Teutonic reinforcements never arrived, with Johann von Tiefen dying on the way.[129] Before long, a plague broke out in the Polish camp, while Vladislaus of Hungary sent an army of 12,000 strong to Moldavia, forcing John Albert to lift the siege on 19 October.[178][179]

The Poles started to march towards Poland, but Stephen ambushed and routed them at a ravine in Bukovina on 25 and 26 October.[168][175][177][180] Several raids into Poland during the following months, including the sacking of Lviv, Yavoriv, and Przemyśl, cemented his victory. These were either ordered and directed by Stephen,[175][181][182][183] or carried out through a combined force of Ottoman–Tatar–Moldavian irregulars commanded by Malkoçoğlu.[184] Stephen made peace with John Albert only after Poland and Hungary concluded a new alliance against the Ottoman Empire,[181] and Moldavia received direct access to Lviv's markets.[185] Meanwhile, the Ottoman campaign ended in disaster, as a heavy winter induced famine; various Polish and Lithuanian reports also suggest that Stephen ordered false flag attacks against his panicking former allies.[186]

Last years

[edit]

From about 1498, power in Moldavia quietly shifted toward a group of boyars and administrators, comprising, among others, Luca Arbore and Ioan Tăutu.[187] Stephen's son and co-ruler, Bogdan, was also taking on princely responsibilities from his father. He conducted the negotiations with Poland about a peace treaty.[188] The treaty, which Stephen ratified at Hârlău in 1499, put an end to Polish suzerainty over Moldavia.[114][179] Stephen again stopped paying tribute to the Ottomans in 1500,[181] although by then his health had declined. In February 1501, his delegation arrived in Venice, asking for a specialist doctor. As reported by Marin Sanudo, his envoys also discussed the possibility of Moldavia and Hungary joining the Ottoman–Venetian War.[189] The Doge of Venice, Agostino Barbarigo, sent a physician, Matteo Muriano, to Moldavia to treat his counterpart.[188][190][191]

Stephen's armies again broke into the Ottoman Empire, but they could not recapture Chilia or Cetatea Albă.[127][181] The Tatars of the Great Horde invaded southern Moldavia, but Stephen defeated them with the support of the Crimean Tatars in 1502.[192] He also sent reinforcements to Hungary to fight against the Ottomans.[192] By then, however, the treaty with Poland was no longer enforced, prompting Stephen to recapture Pocuția in 1502.[190][193][194][195] Although Alexander of Lithuania was by then the new King of Poland, no understanding could be reached between him and Stephen, and the two became enemies.[195] At around that time, Luca Arbore, acting either as Stephen's envoy or on his own, stated a Moldavian claim to Halych and other towns of the Ruthenian Voivodeship.[196] Hungary and the Ottoman Empire concluded a new peace treaty on 22 February 1503, which also included Moldavia.[164][192] Thereafter Stephen again paid a yearly tribute to the Ottomans.[192] Stephen survived his doctor, who died in Moldavia in late 1503.[190][191] Another Moldavian delegation was sent to Venice to ask for a replacement, but also to propose a new alliance against the Ottomans.[191] This was one of his last acts of international diplomacy. When Stephen was dying, various boyars, who opposed Bogdan, rebelled, but they were suppressed.[190][197][198] On his deathbed, he had urged Bogdan to continue to pay the tribute to the Sultan.[179] He died on 2 July 1504 and was buried in the Monastery of Putna.[192][199][200]

Family

[edit]A woman named Mărușca (or Mărica) most probably gave birth to Stephen's first recognized son, Alexandru.[201][202][203] Historian Ioan-Aurel Pop describes Mărușca as Stephen's first wife,[143] but other researchers note that the legitimacy of the Stephen–Mărușca marriage is uncertain.[5][201][202] According to Jonathan Eagles, Alexandru either died in childhood or survived infancy and became his father's co-ruler.[204] This older Alexandru died in July 1496, not before marrying a daughter of Bartolomeu Dragfi, the Transylvanian Voivode.[202][205][206] He is probably not the same Alexandru who, in 1486, was sent by Stephen as a voluntary hostage to Istanbul, where he married a Byzantine noblewoman.[207] This Alexandru was still alive by the end of his father's rule and beyond, when he became a pretender to the throne, and ultimately a contested prince.[208] A 1538 letter by Fabio Mignanelli describes the surviving Alexandru, or "Sandrin", as a posthumous son of Stephen, but this is likely an error.[209]

If Stephen fathered two or three sons named Alexandru, the one who was for a while his designated successor was born to Evdochia of Kiev, whom Stephen married in 1463.[3][202][204] An Olelkovich,[5][210] she was closely related both to Ivan III of Moscow and to Casimir IV of Poland and Lithuania.[204] Stephen's charter of grant to the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos refers to two children of Stephen and Evdochia, Alexandru and Olena.[211] Olena was the wife of Ivan Molodoy, the eldest son of Ivan III, and mother of the usurped heir Dmitry.[113][212][213][214]

Stephen's second (or third) wife, Maria of Mangup, was of the family of the Princes of Theodoro. She was probably also cousins with the Muscovite Grand Princess Sophia Palaiologina and was related to Trebizond's royal couple, Emperor David and Empress Maria.[215] The Stephen–Maria marriage took place in September 1472, but she died in December 1477.[216][217][218] During her brief stay in Moldavia, Maria supported the Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople, contributing to the friendly contacts between Stephen and Catholic powers.[219] Stephen's third (or fourth) wife, Maria Voichița, was the daughter of Radu the Fair, Voivode of Wallachia. She was the mother of Stephen's immediate successor, Bogdan, and a daughter named Maria Cneajna.[220][221] The latter married into the House of Sanguszko.[222] Stephen is known to have fathered two other sons who died in childhood, at a time when he was married to Maria Voichița: Bogdan died in 1479, and Peter (Petrașco) in 1480. Scholars are divided as to whether their mother was Evdochia,[204] Maria of Mangup,[94][213] or a very young Maria Voichița.[223] Bogdan was also known as "Vlad"—a regal name rarely used in Moldavia, but common for Wallachian princes. The choice was either "an underlining of the Moldo–Wallachian unity which Prince Stephen had sought to achieve", or, more precisely but less certainly, a proof that Stephen wished to make Bogdan-Vlad his co-ruler over Wallachia.[224] Archivist Aurelian Sacerdoțeanu believes that Bogdan-Vlad also had a twin, Iliaș.[213]

In 1480, Stephen finally recognized his first-born, Mircea, born from his 1450s affair with Călțuna of Brăila, and groomed him to take the throne in Wallachia. According to Sacerdoțeanu, recognition came only after the death of Mircea's legal father, who may have been one of the boyars spared at Soci.[23] Stephen also fathered another illegitimate son, Petru Rareș, who became prince of Moldavia in 1527.[192][225][226][227] The church regards his mother, Maria Rareș, as Stephen's fourth wife,[2] although she is known to have been married to a burgher.[200] Stephen V "Locust", who held the Moldavian throne in 1538–1540, also presented himself as Stephen's illegitimate son. According to Sacerdoțeanu, his claim is credible.[227] A local tradition in Putna County (today's Vrancea) attributes to Stephen other extra-conjugal affairs, with many peasants reporting that they consider themselves "of his blood" or "of his marrow".[228]

-

Miniature from the 1487, Pătrăuți Monastery

-

Stephen's second (or third) wife, Maria of Mangup

-

Stephen's third (or fourth) wife, Maria Voichița

-

Votive depiction of Stephen, 1503,Dobrovăț Monastery

Legacy

[edit]Stability and violence

[edit]Stephen reigned for more than 47 years,[114][200] which was "in itself an outstanding achievement in the context of the political and territorial fragility of the Romanian principalities".[229] His diplomacy evidenced that he was one of the "most astute politicians" of Europe in the 15th century.[114] This skill enabled him to play off the Ottoman Empire, Poland and Hungary against each other.[114] According to historian Keith Hitchins, Stephen "paid tribute to the Ottomans, but only when it was advantageous...; he did homage to King Casimir of Poland as his suzerain when that seemed wise ...; and he resorted to arms when other means failed."[230]

Stephen suppressed the rebellious boyars and strengthened central government, often applying cruel punishments, including impalement.[231] He consolidated the practice of slavery, including the notion that different laws applied to slaves, reportedly capturing as many as 17,000 Roma during his invasion of Wallachia, but also selectively freeing and assimilating Tatar slaves.[232] He supposedly used both communities as "slaves of the court", treasuring their specialized skills;[233] nevertheless, one folk legend additionally claims that Stephen practiced human sacrifice against Roma slaves, to alleviate the floods at Sulița.[234] According to Marcin Bielski, during the 1498 expedition to Poland, the voivode participated in, or at least tolerated, the capture of as many as 100,000 people.[235][236] At least some of these were colonized in Moldavia, where, according to various reports of the period, they founded "Ruthenian" undefended towns. According to historian Mircea Ciubotaru, these may include Cernauca (now Chornivka in Ukraine), Dobrovăț, Lipnic, Ruși-Ciutea, and a cluster of villages outside Hârlău.[237]

Stephen also welcomed freemen as settlers, establishing some of the first Armenian colonies in Moldavia, including one at Suceava,[238] while also settling Italians, some of whom were escapees from the Ottoman slave trade, in that city.[239][240] Early on, he renewed the commercial privileges of Transylvanian Saxons who traded in Moldavia, but subsequently introduced some protectionist barriers.[29] His own court was staffed with foreign experts, among them Matteo Muriano and the Italian banker Dorino Cattaneo.[240][241] However, as a "crusader" in the 1470s, Stephen encouraged the religious persecution and extortion of Gregorian Armenians, Jews, and Hussites, some of whom became supporters of the Ottoman Empire.[242]

In addition to his colonization policies, Stephen restored Crown lands that had been lost during the civil war that followed Alexander the Good's rule, either through buying or confiscating them.[65][243] On the other hand, he granted much landed property to the Church and to the lesser noblemen who were the main supporters of the central government.[244] His itinerant lifestyle enabled him to personally hold court in the whole of Moldavia, which contributed to the development of his authority.[245]

When talking with Muriano in 1502, Stephen mentioned that he had fought 36 battles, only losing two of them.[246] When the enemy forces mostly outnumbered his army, Stephen had to adopt the tactics of "asymmetric warfare".[247] He practised guerilla warfare against invaders, avoiding challenging them to open battle before they were weakened due to the lack of supplies or sickness.[248] During his invasions, however, he moved quickly and forced his enemies to do battle.[248] To strengthen the defence of his country, he restored the fortresses built during Alexander the Good's rule at Hotin, Chilia, Cetatea Albă, Suceava and Târgu Neamț.[249] He also erected a number of castles, including the new fortresses at Roman and Tighina.[69] The pârcălabi (or commanders) of the fortresses were invested with administrative and judicial powers and became important pillars of royal administration,[250] their work controlled by a new central office, the armaș (first attested in 1489).[29] The pârcălabi included members of the princely family, such as Duma, who was Stephen's cousin;[10] before his execution, Isaia, the voivode's brother-in-law, had supervised Chilia[3] and Neamț Citadel.[12]

Stephen hired mercenaries to man his forts, which diminished the military role of the boyars' retinues within the Moldavian military forces.[251] He also set up a personal guard 3,000 strong[251] and, at least for a while, an Armenian-only unit.[252] To strengthen the defence of Moldavia, he obliged the peasantry to bear arms.[253] Moldavian chronicles recorded that if "he found a peasant lacking arrows, bow or sword, or coming to the army without spurs for the horse, he mercilessly put that man to death".[253] The military reforms increased Moldavia's military potential, enabling Stephen to muster an army of more than 40,000 strong.[254]

Cultural development

[edit]The years following Stephen's wars against the Ottoman Empire have been described as the era of "cultural policies"[255] and "great architectural upsurge".[256] More than a dozen stone churches were erected at Stephen's initiative after 1487.[256] The wealthiest boyars followed him, and Stephen also supported the development of monastic communities.[257] For instance, the Voroneț Monastery was built in 1488 and the monastery at Tazlău in 1496 to 1497.[257]

The style of the new churches evidences that a "genuine school of local architects" developed during Stephen's reign.[257][258] They borrowed components of Byzantine and Gothic architecture and mixed it with elements of local tradition.[257] Painted walls and towers with a base forming a star were the most featuring elements of Stephen's churches.[259] The prince also financed the building of churches in Transylvania and Wallachia, which contributed to the spread of Moldavian architecture beyond the boundaries of the principality.[257] Stephen commissioned votive paintings and carved tomb stones for many of his ancestors' and other relatives' graves.[260] The tomb room of the Putna Monastery was built to be the royal necropolis of Stephen's family.[261] Stephen's own tombstone was decorated with acanthus leaves (a motif adopted from Byzantine art) which became the featuring decorative element of Moldavian art during the following century.[262]

Stephen also contributed to the development of historiography and Church Slavonic literature in Moldavia. He ordered the collection of the annals of the principality and initiated the completion of at least three Slavonic chronicles,[263][264] noted in particular for doing away with the conventions of Byzantine literature, and for introducing new storytelling canons.[265] Some portions of these historiographic texts were corrected, and perhaps even dictated, by Stephen himself.[190] The Chronicle of Bistrița, which was allegedly the oldest chronicle, narrated the history of Moldavia from 1359 to 1506.[263][264][266][267] The two versions of the Chronicle of Putna covered the period from 1359 to 1526, but it also wrote of the history of the Putna Monastery.[263][264] They were accompanied by a large number of lay and religious texts (including the Gospels, in several versions by Teodor Mărișescul; as well as commentary on the Nomocanon and Slavonic translations from John Climacus). Some were richly decorated with miniatures, such as portraits of Stephen (in the Humor Monastery Gospel, 1473) and his courtier Ioan Tăutu (Psalter of Mukachevo, 1498).[268] The "Moldavian style", developed at Neamț Monastery by the disciples of Gavriil Uric,[269] became influential outside Moldavia, creating a fashion among Russian illustrators and calligraphers.[270]

National hero

[edit]Stephen received the sobriquet "Great" shortly after his death.[271] Sigismund I of Poland and Lithuania referred to him as "that great Stephen" in 1534.[272] The Polish historian Martin Kromer mentioned him as the "great prince of the Moldavians."[271][273] According to Maciej Stryjkowski, by 1580 the Wallachians and Moldavians alike sang ballads honoring Stephen, whose portrait was displayed at the court of Bucharest; his raids in Wallachia were generally overlooked in such testimonials.[274] Despite being honored for his skill, he was still primarily known under sobriquets indicating his standing and age: in 16th-century Moldavia and Wallachia, he was casually known as Ștefan cel Vechi and Ștefan cel Bătrân ("Stephen the Ancient" or "the Old").[275] Oral history also maintained Stephen's Byzantine self-references, often calling him an "emperor" or a "crai (king) of the Moldavians".[276]

In the mid-17th-century, Grigore Ureche described Stephen as "a benefactor and a leader" when writing of his funeral.[272][277] A boyar by birth, Ureche also mentioned Stephen's despotic cruelty, bad temper, and diminutive stature — possibly because, according to scholar Lucian Boia, he resented authoritarian princes.[278] In tandem, local folklore came to regard Stephen as a protector of peasantry against noblemen and foreign invaders.[279] For centuries, free peasants claimed that they inherited their landed property from their ancestors to whom it had been granted by Stephen for their bravery in the battles.[280][281][282][283]

Such precedents also made Stephen a cult figure in Romanian nationalism, which sought the union of Moldavia with Wallachia, and in rival Moldovenism. Early in the 19th century, the Moldavian regionalist Gheorghe Asachi made Stephen the topic of historical fiction, popular prints, and heraldic reconstructions.[284][285] Asachi, and later Teodor Balș, also campaigned for the erection of a Stephen the Great statue, which was supposed to represent resistance against Wallachian encroachment.[286] The Moldavian separatist Nicolae Istrati wrote several theatrical works which contributed to the Stephen cult.[287] Other Moldavians, shunning separatism, paid their own homage to the medieval hero. In the 1840s, Alecu Russo inaugurated the effort to collect and republish folklore about Stephen, which he believed was the "source of truth" about Romanian history.[288] One of the first epic poems to deal with the voivode was "The Aprod Purice", by Constantin Negruzzi, which fictionalizes the battle of Șcheia.[289][290] In the Bessarabia Governorate, which had been carved out of Moldavia by the Russian Empire, the peasantry and intellectual class both appealed to Stephen as a symbol of resistance.[291] His "golden century" was a reference for Alexandru Hâjdeu[292] and Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu. The latter dedicated him a large number of works, from poems written in his native Russian to Romanian-language historical novels in which Stephen is a leading protagonist.[293]

By then, the cult of Stephen's "patriotic virtues" had been introduced to Wallachia by Ienăchiță Văcărescu and Gheorghe Lazăr.[294] Wallachian scholar Nicolae Bălcescu was the first Romanian historian to describe Stephen as a national hero; his rule, Bălcescu argued, was an important step towards the unification of the lands inhabited by Romanians.[295] During that period, Stephen became explicitly mentioned in the Romantic poetry of Andrei Mureșanu, in particular as the "mighty shadow" described in Romania's future national anthem.[296] In 1850s Wallachia, Dimitrie Bolintineanu produced a lukewarm ballad depicting Stephen fleeing for battle, and his mother Oltea ordering him back.[297] It became a hugely popular after being set to music.[298] His later works also contribute to the nationalist cult, or fictionalize his erotic life.[299] The nationalist investment in Stephen was by then resisted by other writers, in particular George Panu, Ioan Bogdan, and other Junimea members, who favored a critique of Romantic nationalism. In Panu's works, Stephen appears as merely a "Polish vassal"; the one-time Junimist A. D. Xenopol also chided the voivode for his loss of Chilia and his supposed betrayal of Wallachia.[300]

Anniversaries of the most important events of Stephen's life have been officially celebrated since the 1870s,[301] including in 1871 the defiant show of solidarity at Putna. This doubled as a protest against Austria-Hungary, which had annexed Bukovina; it was organized by Teodor V. Ștefanelli and was notably attended by poet Mihai Eminescu.[302] Nationalist interpretations still prevailed, particularly after 1881, when Eminescu dedicated his poem Doina (written in the style of traditional Romanian song) to Stephen, calling upon him to leave his grave to again lead his people.[295][303][304] His statue was ultimately raised in Iași in 1883.[301][305]

On the 400th anniversary of the voivode's death in 1904, ceremonies included the completion of a stone monument in Bârsești, by locals who claimed descent from Vrâncioaia.[306][307] Also then, Nicolae Iorga published Stephen's biography.[308] Against Xenopol's verdict, Iorga emphasized that Stephen's victories were to be attributed to the "true unity of the whole people" during his reign.[309] Many more works of literature appeared in the Kingdom of Romania and other Romanian-inhabited regions, helping to consolidate Stephen's cultural legacy. One such contribution was the 1909 play Apus de soare, by Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea, including advice attributed, in the public's mind, to historical Stephen:

Moldavia was not my ancestors', was not mine, and is not yours, but belongs to our descendants and our descendants' descendants to the end of time.[310]

Depicting Stephen as a dying sage, it was followed by two other Delavrancea plays, which insisted on the prince's pragmatic cruelty and the effects this had on his succession.[311] By then, Stephen as a statesman had also become a point of reference and a benchmark for the long and stabilizing rule of Carol I, King of Romania.[312] Over the following three decades, Stephen's deeds became the inspiration for literary works by Iorga, Mihai Codreanu, and especially Mihail Sadoveanu.[313] In the 1930s, the Iron Guard embraced Stephen the Great's cult for its own purposes, with special emphasis on his contribution as a Christian monarch.[314]

The reading of Stephen as a pan-Romanian nationalist peaked during the late stages of Communist Romania. Initially, the regime looked down on Stephen's treatment of the peasantry, and only emphasized his connections with the East Slavs or his clampdown against boyardom.[315] This stance was overturned by national communism. Initially, censorship toned down or removed references to his legacy in Soviet Bessarabia or Pokuttya;[316] in the 1980s, however, official historians claimed that Stephen was literally a "lord of all Romanians".[317] Iorga's book has been republished several times, including on the 500th anniversary of Stephen's death.[318] On the same anniversary, Stephen was presented as a symbol of "national identity, independence and inter-ethnic harmony" in the Republic of Moldova,[308] where he also endures as the symbol of "Moldavian particularism"[319] or "Moldovan patriotism".[320] Thus, Stephen was invoked by both the Popular Front of Moldova, which favored Romanian identity, and the Moldovenist Party of Communists.[321] The latter describes Stephen as "the founder of Moldavian statehood", claiming direct continuity from his principality to the present-day state.[322]

As Eagles notes, "Stephen is an ever-present icon" in both Romania and Moldova: "statues of his image abound; politicians cite him as an exemplar; schools and a university bears his name; villages and the main thoroughfares of towns and cities are named after him; there is a Ștefan cel Mare metro station in central Bucharest; and his crowned head has adorned every banknote in the post-Soviet Moldovan republic".[323] According to a 1999 opinion poll, more than 13% of the participants regarded Stephen the Great as the most important personality who had "influenced the destiny of the Romanians for the better".[324] Seven years later, during a programme called the 100 Greatest Romanians on Romanian Television, he was voted "the greatest Romanian of all time".[301]

Holy ruler

[edit]Stephen the Great | |

|---|---|

Miniature, 1473 medieval manuscript, the Tetraevangelion Gospel from the Humor Monastery | |

| Holy Voivode | |

| Venerated in | Romanian Orthodox Church and other Eastern Orthodox Jurisdictions |

| Canonized | 12 July 1992, Bucharest, Romania by Romanian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Putna Monastery |

| Feast | 2 July |

In Athonite legends, Romanian stories, and Moldavian chronicles alike, Stephen's victories against the Ottomans and Hungarians were already regarded as God-inspired, or as placed under the direct patronage of various saints (George, Demetrius, Procopius, or Mercurius).[325][326] Veneration of Stephen himself was first recorded in the 1570s,[252] but, according to Ureche, he had been regarded as a saint soon after his funeral: "not on account of his soul ... for he was a man with sins ... but on account of the great deeds he accomplished".[277] The positive nuances of Ureche's report were also repeated by Miron Costin.[277]

The abbot of Putna Monastery, Artimon Bortnic, initiated the investigation of the tomb room of the monastery in 1851, referring to important shrines in Russia and Moldavia.[327] In 1857 (a year after Stephen's tomb was opened), the priest and journalist Iraclie Porumbescu already wrote of the "holy bones of Putna".[328] In at least some legends attested by 1903, the voivode is depicted as an immortal sleeping hero, or, alternatively, as the ruler of heaven.[329] However, Stephen the Great was ignored when the Romanian Orthodox Church canonized the first Romanian saints in the 1950s.[330]

Teoctist, Patriarch of All Romania, canonized Stephen along with 12 other saints at Saint Spyridon the New Church in Bucharest on 21 June 1992.[331] On this occasion, the patriarch emphasized that Stephen had been a defender of Christianity and protector of his people.[264] He also underlined that Stephen had built churches during his reign.[264] Stephen's feast day is 2 July (the day of his death) in the calendar of the Romanian Orthodox Church. On his first feast after his canonization, a new ceremony was held to celebrate Stephen the Great and Saint in Putna.[331] 15,000 people (including the President of Romania at the time, Ion Iliescu, and two ministers) attended the event.[332] Patriarch Teoctist noted that "God has brought us together under the same skies, just as Stephen rallied us under the same flag in the past."[332]

Arms

[edit]Stephen's rule consolidated the usage of the coat of arms of Moldavia, featuring the aurochs head (first attested in 1387), sometimes as a helmet atop his personal arms. He revived the elaborate design introduced under Alexander the Good, which also featured a rose, crescent, sun and star (often, but not always, five-pointed); its tinctures remain unknown.[333] This arrangement was not familiar to heraldists in Western Europe. By the 1530s, they represented Moldavia with attributed arms featuring Maures; these arms, though originally used for Wallachia, possibly echoed Stephen's victories over the Ottomans.[334]

The personal arms and heraldic flags used by Stephen have been the topic of additional scrutiny and debate. Stephen is known to have used a party per cross shield with one striped quarter, but the colors are uncertain: one prevailing interpretation is that the dominant tinctures were or and vert, although they may also have been gules and argent. These may derive from the colors used by the House of Basarab (which were possibly used by Stephen's in-law Radu the Handsome), from the coat of arms of Hungary, or from a purely Moldavian tradition.[335] The division and the striped pattern are possibly Hungarian; they survived in some of Stephen's seals even during his dispute with the Hungarian crown. He also continued to use the fleur-de-lis, an Angevin symbol, but altered it into a "double-headed lily", then renounced it altogether.[336] Similarly, he used the Cross of Lorraine, pattée, possibly in reference to the Pahonia. Following his 1489 dispute with Poland, that charge was altered into a double cross fleury.[337]

Stephen's heraldic symbols progressively merged with those attributed to the House of Mușat, and were intensively used by all princes who claimed full or partial descent from Alexander the Good—including Peter the Lame, a Wallachian pretender to Moldavia's throne.[338] The Putna tombstones of Stephen's two sons who died during his lifetime, Bogdan and Peter, already display the aurochs within the "Mușat coat-of-arms".[339][340]

A Moldavian banner also survives in hand-colored versions illustrating Johannes de Thurocz's Chronica Hungarorum, with varying tinctures. These were first identified as Stephen's flags by Constantin Karadja, and described by later authors as a version of the or-an-vert scheme in the coat of arms.[341] Other clues suggest that the field was a solid one of or, charged with an aurochs of or, but also that the preferred "single Moldavian" color was gules.[342] Gules is also the color of Stephen's alleged war flag, defaced with an icon of Saint George and the Dragon and donated by the prince himself to Zograf monastery. However, scholar Petre Ș. Năsturel cautions that this may not be a heraldic object of any kind, but rather a votive offering. The "war flag", he notes, is too small to carry in battle, and does not match with images in either Thurocz or Marcin Bielski, nor with the description in Alexander Guagnini.[343]

-

Stephen's seal, with legend in Old Church Slavonic

-

Modern drawing of the coat of arms

-

One variant of Stephen's personal coat of arms, with hypothetical tinctures

-

Moldavian warrior and flag, uncolored version in Johannes de Thurocz. 1467.

-

One interpretation of the Thurocz flag, featuring or-an-vert stripes. 1467.

See also

[edit]- Neamț Citadel

- Borzești Church

- Ștefan cel Mare, Argeș

- Ștefan cel Mare, Bacău

- Ștefan cel Mare, Călărași

- Ștefan cel Mare, Neamț

- Ștefan cel Mare, Olt

- Ștefan cel Mare, Vaslui

- Saligny, Constanța

References

[edit]- ^ a b Păun 2016, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Iliescu 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e f g Demciuc 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b Florescu & McNally 1989, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 38.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 190.

- ^ Brezianu & Spânu 2007, p. 338.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Eșanu 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ a b c Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 40.

- ^ a b Pop 2005, p. 256.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Rezachievici 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 31, 212.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Treptow 2000, p. 59.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Treptow 2000, pp. 58, 61.

- ^ Treptow 2000, p. 98.

- ^ a b Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 38, 40–41.

- ^ a b c Treptow 2000, p. 99.

- ^ a b Rezachievici 2007, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 5.

- ^ Rezachievici 2007, pp. 17–18, 20–30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Demciuc 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Rezachievici 2007, pp. 25, 27.

- ^ a b c Pop 2005, p. 266.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 106–108, 138.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Mureșan 2008.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 102–180.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 38, 213.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Ciobanu 1991, p. 43.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eagles 2014, p. 213.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Mureșan 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Treptow 2000, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Ciobanu 1991, p. 44.

- ^ Treptow 2000, p. 136.

- ^ Treptow 2000, p. 138.

- ^ Treptow 2000, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Treptow 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Florescu & McNally 1989, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Florescu & McNally 1989, p. 149.

- ^ a b Treptow 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 38.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Pop 2005, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 3, 4.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 94.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 4, 5.

- ^ a b Kubinyi 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Kubinyi 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 302.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Tiron 2012, pp. 76, 79.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Eagles 2014, p. 214.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f Ciobanu 1991, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d e Demciuc 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b Brezianu & Spânu 2007, p. xxvi.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 42.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 316–324.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Cristea 2016, p. 316.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Pop 2005, p. 267.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Demciuc 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Florescu & McNally 1989, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagles 2014, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mikaberidze 2011, p. 914.

- ^ a b c d Shaw 1976, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 116.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 48.

- ^ a b Cândea 2004, p. 141.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 317–318, 325.

- ^ a b c Eagles 2014, p. 46.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Treptow 2000, p. 160.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 44, 52.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Papacostea 1996, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Demciuc 2004, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Pop 2005, p. 268.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 116-117.

- ^ Hârnea 1979, pp. 49–57.

- ^ Iliescu 2006, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Cristea 2016, p. 343.

- ^ a b Treptow 2000, p. 162.

- ^ a b Pilat 2010, p. 125.

- ^ Florescu & McNally 1989, pp. 173–175.

- ^ a b Treptow 2000, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Papacostea 1996, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Ciobanu 1991, p. 49.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagles 2014, p. 216.

- ^ Shaw 1976, p. 70.

- ^ Shaw 1976, pp. 70, 72.

- ^ Florescu & McNally 1989, p. 45.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Cristea 2016, p. 338.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Demciuc 2004, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 118.

- ^ Kubinyi 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 308.

- ^ a b c d Shaw 1976, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Parry 1976, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Kohn 2007.

- ^ Gemil 2013, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 59.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Cernovodeanu 1977, p. 118.

- ^ Diaconescu 2013, pp. 91–96.

- ^ Diaconescu 2013, pp. 96–110.

- ^ Diaconescu 2013, pp. 94–98.

- ^ a b c Papacostea 1996, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Bain 1908, p. 29.

- ^ a b Maasing 2015, p. 362.

- ^ a b Ciobanu 1991, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Pilat 2010, p. 127.

- ^ a b Parry 1976, pp. 58, 60.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 127, 129.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 8, 9.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Ciobanu 1991, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagles 2014, p. 217.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 24, 59.

- ^ a b Mărculeț 2006.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, pp. 60, 217.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Gorovei 1973, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Pop 2005, p. 269.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 132, 135.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Pilat 2010, pp. 131–136.

- ^ a b Pop 2005, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d e f Demciuc 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 317.

- ^ Bain 1908, p. 30.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 345.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 345–347.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 347.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 63.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 359–360.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 62.

- ^ Diaconescu 2013, pp. 97, 109.

- ^ a b Frost 2015, p. 327.

- ^ Frost 2015, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 64.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 285.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 360.

- ^ a b Nowakowska 2007, p. 46.

- ^ a b Frost 2015, p. 281.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b c Bain 1908, p. 43.

- ^ a b Eșanu 2013, pp. 137–138, 140.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 315, 319.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 66.

- ^ Cristea 2016, p. 319.

- ^ a b c Nowakowska 2007, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e f Demciuc 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Gemil 2013, p. 40.

- ^ a b Grabarczyk 2010.

- ^ Nowakowska 2007, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Eagles 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Nowakowska 2007, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d Eagles 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Ciubotaru 2005, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Gorovei 2014.

- ^ Gorovei 2014, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Gorovei 2014, p. 408.

- ^ Eșanu 2013, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Marin 2009, pp. 85–87.

- ^ a b c d e Demciuc 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Marin 2009, pp. 87–91.

- ^ a b c d e f Eagles 2014, p. 219.

- ^ Bain 1908, p. 52.

- ^ Ciubotaru 2005, p. 71.

- ^ a b Eșanu 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Eșanu 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 50, 219.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 4, 12.

- ^ a b c Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 39.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Mureșan 2008, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 38, 41, 45.

- ^ a b c d Eagles 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 9, 10.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 41, 45.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 139–141, 159–160, 168–171.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 141, 168–170, 174–175.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 102, 135.

- ^ Păun 2016, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Brezianu & Spânu 2007, p. 339.

- ^ a b c Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 45.

- ^ Eșanu 2013, pp. 138–139, 141.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 136, 138.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Demciuc 2004, pp. 5, 7.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 46, 50, 103.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 39, 45, 47.

- ^ Sacerdoțeanu 1969, p. 47.

- ^ Voiculescu 1991, pp. 85, 87.

- ^ Voiculescu 1991, p. 87.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 160.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 172, 173, 175, 143.

- ^ a b Sacerdoțeanu 1969, pp. 39, 47.

- ^ Iliescu 2006, p. 71.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Hitchins 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Achim 2004, pp. 17, 35–36.

- ^ Emandi 1994, p. 322.

- ^ Oișteanu 2009, p. 428.

- ^ Ciubotaru 2005, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Gorovei 2014, pp. 407–408.

- ^ Ciubotaru 2005, pp. 70–77.

- ^ Siruni 1944, pp. 11, 19, 25, 61.

- ^ Ciubotaru 2005, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Emandi 1994, p. 321.

- ^ Siruni 1944, p. 27.

- ^ Simon 2009, pp. 233–239.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 54.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 27.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 41.

- ^ a b Simon 2009, p. 233.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Mărculeț 2006, p. 189.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c d e Papacostea 1996, p. 71.

- ^ Pop 2005, p. 296.

- ^ Pop 2005, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 185.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 99.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Pop 2005, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d e Eagles 2014, p. 78.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Mitric 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, p. 669.

- ^ Mitric 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Turdeanu 1951.

- ^ Mitric 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 75.

- ^ a b Papacostea 1996, p. 76.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Mureșan 2008, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Schipor 2004, p. 200.

- ^ a b c Eagles 2014, p. 77.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Pelivan et al. 2012, pp. 44, 85, 275, 566, 589, 591.

- ^ Hârnea 1979, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Iliescu 2006, pp. 68–71.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 365–370.

- ^ Xenopol 1910, pp. 331, 339.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 240, 581–583.

- ^ Schipor 2004, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 382, 389.

- ^ Xenopol 1910, p. 211.

- ^ Pelivan et al. 2012, pp. 44, 85, 102, 116, 136, 158–159, 275, 362, 566, 589.

- ^ Pelivan et al. 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 676–678, 686–693.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 162, 252.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 80.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, p. 570.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 207.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, p. 547.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, pp. 542–544, 547–548.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 57, 135, 189–190.

- ^ a b c Eagles 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Cândea 1937, pp. 7–10.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 194–195, 213.

- ^ Papacostea 1996, p. 80.

- ^ Dima et al. 1968, p. 676.

- ^ Hârnea 1979, pp. 57, 124, 135.

- ^ Iliescu 2006, pp. 71–82.

- ^ a b Eagles 2014, p. 89.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Lovinescu 1998, pp. 299–302.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Lovinescu 1998, pp. 121, 178, 183, 323.

- ^ Bruja 2004.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 215, 219.

- ^ Otu 2019, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Boia 2001, pp. 140, 222, 249–250.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 140.

- ^ Cojocari 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Cojocari 2007, pp. 90–97, 100–102.

- ^ Cojocari 2007, pp. 101–104.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Cristea 2016, pp. 316–340.

- ^ Schipor 2004, p. 206.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 110.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 93.

- ^ Schipor 2004, p. 202.

- ^ Boia 2001, p. 73.

- ^ a b Ramet 1998, p. 195.

- ^ a b Ramet 1998, p. 196.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 83–85, 98–120.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 77–81, 126.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 67–68, 107, 110.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 109, 111–112, 119–120.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 118, 119.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 96, 99–100, 102–108, 111–120.

- ^ Cernovodeanu 1977, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Eagles 2014, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Tiron 2012, pp. 71–75.

- ^ Tiron 2012, pp. 76–80.

- ^ Năsturel 2005, pp. 48–49.

Bibliography

[edit]- Achim, Viorel (2004). The Roma in Romanian History. Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9241-84-9.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1908). Slavonic Europe. A Political History of Poland and Russia from 1447 to 1796. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 500231652.

- Boia, Lucian (2001). History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9116-97-1.

- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98091-0-3.

- Brezianu, Andrei; Spânu, Vlad (2007). Historical Dictionary of Moldova. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5607-3.

- Bruja, Radu-Florian (2004). "Ștefan cel Mare în imagologia legionară". Codrul Cosminului (10): 93–97. ISSN 1224-032X.

- Cândea, Romulus (1937). Arborosenii: trădători austriaci și naționaliști români. Tipografia Mitropolitul Silvestru. OCLC 953017618.

- Cândea, Virgil (2004). "Saint Stephen the Great in his contemporary Europe (Respublica Christiana)". Études balkaniques (4): 140–144. ISSN 0324-1645.

- Cernovodeanu, Dan (1977). Știința și arta heraldică în România. Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. OCLC 469825245.

- Ciobanu, Veniamin (1991). "The equilibrium policy of the Romanian principalities in East-Central Europe, 1444–1485". In Treptow, Kurt W. (ed.). Dracula: Essays on the Life and Times of Vlad the Impaler. East European Monographs, Distributed by Columbia University Press. pp. 29–52. ISBN 0-88033-220-4.

- Ciubotaru, Mircea (2005). "O problemă de demografie istorică de la sfârșitul domniei lui Ștefan cel Mare". Analele Putnei. I (1): 69–78. ISSN 1841-625X.

- Cojocari, Ludmila (2007). "Political Liturgies and Concurrent Memories in the Context of Nation-Building Process in Post-Soviet Moldova: The Case of 'Victory Day'". Interstitio: East European Review of Historical Anthropology. 1 (2): 87–116. ISSN 1857-047X.

- Cristea, Ovidiu (2016). "Guerre, Histoire et Mémoire en Moldavie au temps d'Étienne le Grand (1457–1504)". In Păun, Radu G. (ed.). Histoire, mémoire et dévotion. Regards croisés sur la construction des identités dans le monde orthodoxe aux époques byzantine et post-byzantine. La Pomme d'or. pp. 305–344. ISBN 978-2-9557042-0-2.

- Demciuc, Vasile M. (2004). "Domnia lui Ștefan cel Mare. Repere cronologice". Codrul Cosminului (10): 3–12. ISSN 1224-032X.

- Diaconescu, Marius (2013). "Contribuții la datarea donației Ciceului și Cetății de Baltă lui Ștefan cel Mare". Analele Putnei. IX (1): 91–112. ISSN 1841-625X.

- Dima, Alexandru; Chițimia, Ion C.; Cornea, Paul; Todoran, Eugen (1968). Istoria literaturii române. II: De la Școala Ardeleană la Junimea. Editura Academiei. OCLC 491284551.

- Eagles, Jonathan (2014). Stephen the Great and Balkan Nationalism: Moldova and Eastern European History. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-353-8.

- Emandi, Emil Ioan (1994). "Urbanism și demografie istorică (Suceava în secolele XV–XIX)". Hierasus. IX: 313–362. ISSN 1582-6112.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.