Typikon

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

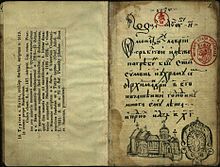

A typikon (or typicon, pl. typica; Greek: Τυπικόν, "that of the prescribed form"; Slavonic: Типикон, сиесть Устав - Tipikon or Ustav[1]) is a liturgical book which contains instructions about the order of the Byzantine Rite office and variable hymns of the Divine Liturgy.

Historical development

[edit]Cathedral Typikon

[edit]The ancient and medieval cathedral rite of Constantinople, called the "asmatikē akolouthia" ("sung services"), is not well preserved and the earliest surviving manuscript dates from the middle of the eighth century.[note 1] This rite reached its climax in the Typikon of the Great Church (Hagia Sophia) which was used in only two places, its eponymous cathedral and in the Basilica of Saint Demetrios in Thessalonica; in the latter it survived until the Ottoman conquest and most of what is known of it comes from descriptions in the writings of Saint Symeon of Thessalonica.

Monastic Typikon

[edit]Typika arose within the monastic movements of the early Christian era to regulate life in monasteries and several surviving typika from Constantinople, such as those of the Pantokrator monastery and the Kecharitomene nunnery, give us an insight into ancient Byzantine monastic life and habits. However, it is the typikon of the Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas the Sanctified near Jerusalem that came to be synthesized with the above-mentioned cathedral rite and whose name is borne by the typikon in use today by the Byzantine Rite.

In his Lausaic History, Palladius of Galatia, Bishop of Helenopolis, records that the early Christian hermits not only prayed the Psalms, but also sang hymns and recited prayers (often in combinations of twelve).[2] With the rise of Cenobitic monasticism (i.e., living in a community under an Abbot, rather than as solitary hermits), the cycle of prayer became more fixed and complex, with different ritual practices in different places. Egeria, a pilgrim who visited the Holy Land about 381–384, recorded the following:

But among all things it is a special feature that they arrange that suitable psalms and antiphons are said on every occasion, both those said by night, or in the morning, as well as those throughout the day, at the sixth hour, the ninth hour, or at lucernare, all being so appropriate and so reasonable as to bear on the matter in hand. (XXV, 5) [3]

The standardization of what became Byzantine monastic worship began with Saint Sabbas the Sanctified (439–532), who recorded the office as it was practiced at his time in the area around Jerusalem, passing on what had been handed down to him by St. Euthymius the Great (377–473) and St. Theoktistos (c. 467). This area was at the time a major center of both pilgrimage and monasticism, and as a result the daily cycle of services became highly developed. St. Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem (560–638) revised the Typikon, and the material was then expanded by St. John Damascene (c. 676 – 749). This ordering of services was later known as the Jerusalem or Palestinian or Sabbaite Typikon. Its usage was further solidified when the first printed typikon was published in 1545. It is still in widespread use among most Byzantine monastic communities worldwide as well as in parishes and cathedrals in large swaths of Eastern Orthodoxy, notably, in Russia.

Synthesis

[edit]In the 8th century, the development of monastic liturgical practice was centered in the Monastery of the Stoudios in Constantinople where the services were further sophisticated, in particular with regard to Lenten and Paschal services and, most importantly, the Sabbaite Typikon was imported and melded with the existing typikon; as Fr. Robert F. Taft noted,

How the cathedral and monastic traditions meld into one is the history of the present Byzantine Rite. ... [St. Theodore the Studite] summoned to the capital some monks of St. Sabas to help combat iconoclasm, for in the Sabaitic chants Theodore discerned a sure guide of orthodoxy, he writes to Patriarch Thomas of Jerusalem. So it was the office of St. Sabas, not the [sung service] currently in use in the monasteries of Constantinople, which the monks of Stoudios would synthesize with material from the asmatike akolouthia or cathedral office of the Great Church to create a hybrid "Studite" office, the ancestor of the one that has come down to us to this day: a Palestinian horologion with its psalmody and hymns grafted onto a skeleton of litanies and their collects from the euchology of the Great Church. Like the fusion of Anglo-Saxon and French in the formation of English, this unlikely mongrel would stand the test of time.[note 2]

The typika in contemporary use evolved from this synthesis.

Modern Typika

[edit]The Russian Orthodox Church inherited only the monastic Sabbaite typikon, which is used to this day[1] in parishes and cathedrals as well as in monasteries.

However, some remnant of the cathedral rite remained in use elsewhere in the Byzantine Rite world, as is evidenced by, for example, the Divine Liturgy commencing at the end of matins and the all-night vigil's use only on occasions when a service that actually lasts through the whole night is served.

With the passage of time, the rite evolved but no descriptive typikon was published until 1839 when, finally, Constantine Byzantios, the Protopsaltes of the Great Church, composed and published the typikon twice in Greek as The Ecclesiastical Typikon according to the Style of the Great Church of Christ[note 3] and once in Slavonic;[4] in 1888, George Violakis, then the Protopsaltes of the Great Church, wrote a report correcting mistakes and ambiguities in Byzantios' typika and later published the completed and corrected typikon as Typikon of the Great Church of Christ[note 4][5] which is still in use today,[6] in most of the Byzantine Rite, excluding the churches of the Russian tradition. This typikon is often described as prescriptive and an innovation; however, as Bishop Kallistos Ware noted,

"In making these and other changes, perhaps Violakes was not innovating but simply giving formal approval to practices which had already become established in parishes.[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As quoted in Taft, "Mount Athos...", Description in A. Strittmatter, "The 'Barberinum S. Marci'of Jacques Goar," EphL 47 (1933), 329-67

- ^ As quoted in Taft, "Mount Athos...", p 182

- ^ Τυπικὸν Ἐκκλησιαστικὸν κατὰ τὸ ὕφος τῆς τοῦ Χριστοῦ Μεγάλης Ἐκκλησίας.

- ^ Τυπικὸν τῆς τοῦ Χριστοῦ Μεγάλης Ἐκκλήσιας, Tipikon tis tou Christou Megalis Ekklisias

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Тvпико́нъ сіесть уста́въ (Title here transliterated into Russian; actually in Church Slavonic) (The Typicon which is the Order), Москва (Moscow, Russian Empire): Сvнодальная тvпографiя (The Synodal Printing House), 1907, p. 1154

- ^ Lausaic History, Chap. 19, etc.

- ^ Tr. Louis Duchesne, Christian Worship (London, 1923).

- ^ [1] "Ecumenical Patriarchate – Byzantine music — Constantine Byzantios – Archon Protopsaltes of the Great Church of Christ", Retrieved 2011-12-30

- ^ Bogdanos, Theodore (1993), The Byzantine Liturgy: Hymnology and Order, Greek Orthodox Diocese of Denver Choir Federation, p. xviii, ISBN 978-1-884432-00-2

- ^ [2] "Ecumenical Patriarchate – Byzantine music — George Violakis – Archon Protopsaltes of the Great Church of Christ", Retrieved 2011-12-30

- ^ Mother Mary; Archimandrite Kallistos Ware (1984), The Festal Menaion, London: Faber and Faber, p. 543, ISBN 978-0-8130-0666-6

References

[edit]- Archpriest Alexander Schmemann (1963), Introduction to Liturgical Theology (Lib. of Orthodox Theol.), Faith Press Ltd (published 1987), p. 170, ISBN 978-0-7164-0293-0

- Archimandrite Robert F. Taft, S.J. (1988), "Mount Athos: A Late Chapter in the History of the Byzantine Rite", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 42: 179–194, doi:10.2307/1291596, JSTOR 1291596

- Archimandrite Robert F. Taft, S.J. (1986), The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West: The Origins of the Divine Office and Its Meaning for Today, Collegeville, Minnesosta: The order of Saint Benedict, Inc., p. 423, ISBN 978-0-8146-1405-1, JSTOR 1291596

- Ware, Timothy (1963), The Orthodox Church, London, UK: Penguin Books (published 1987), p. 193, ISBN 978-0-14-013529-9

Further reading

[edit]- Getcha, Archbishop Job. (2012) [2009]. Le Typikon décrypté: Manuel de liturgie de byzantine [The Typikon Decoded. An explanation of Byzantine Liturgical Practice.] (in French). Translated by Meyendorff, Paul. Paris: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88225-014-4.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- (in Slavonic) The Typicon of Saint Sabbas as used in the Russian Church

- Edited translation of much of the 1907 Moscow edition of Typikon of St. Sabbas, with commentary, Archbishop Averky — Liturgics", Retrieved 2011-11-15

- (in Greek) Typicon for the current year (and other information) based on Violakis' work and other descriptive practices

- A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology - Part 2, Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D., Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, referenced December 27, 2006

- Great Lent, Holy Week, and Pascha in the Greek Orthodox Church, Rev. Alkiviadis Calivas, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, referenced December 27, 2006

- Typikon of the Russian Orthodox Church, Translation project

- Online Greek Orthodox Typikon

- Typikon of Gregory Pakourianos for the Monastery in Bačkovo

- 1888 Violakis Typikon of the Great Church of Constantinople, draft of the English translation from the Arabic edition, prepared by the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

- A Brief History of the Typicon