Operation Storm

| Operation Storm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence, Bosnian War and the Inter-Bosnian Muslim War | |||||||||

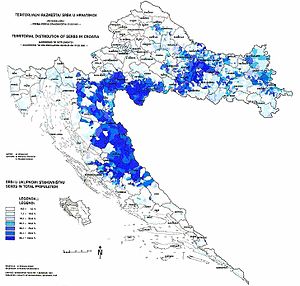

Map of Operation Storm Forces: Croatia RSK Bosnia and Herzegovina | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

174–211 killed 1,100–1,430 wounded 3 captured |

560 killed 4,000 POWs | ||||||||

|

Serb civilian deaths: 214 (Croatian claim) – 1,192 (Serb claim) Croat civilian deaths: 42 Refugees: 150,000–200,000 Serbs from the former RSK 21,000 Bosniaks from the former APWB 22,000 Bosniaks and Croats from the RS Other: 4 UN peacekeepers killed and 16 wounded | |||||||||

Operation Storm (Serbo-Croatian: Operacija Oluja / Операција Олуја) was the last major battle of the Croatian War of Independence and a major factor in the outcome of the Bosnian War. It was a decisive victory for the Croatian Army (HV), which attacked across a 630-kilometre (390 mi) front against the self-declared proto-state Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), and a strategic victory for the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). The HV was supported by the Croatian special police advancing from the Velebit Mountain, and the ARBiH located in the Bihać pocket, in the Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina's (ARSK) rear. The battle, launched to restore Croatian control of 10,400 square kilometres (4,000 square miles) of territory, representing 18.4% of the territory it claimed, and Bosniak control of Western Bosnia, was the largest European land battle since World War II. Operation Storm commenced at dawn on 4 August 1995 and was declared complete on the evening of 7 August, despite significant mopping-up operations against pockets of resistance lasting until 14 August.

Operation Storm was a strategic victory in the Bosnian War, effectively ending the siege of Bihać and placing the HV, Croatian Defence Council (HVO) and the ARBiH in a position to change the military balance of power in Bosnia and Herzegovina through the subsequent Operation Mistral 2. The operation built on HV and HVO advances made during Operation Summer '95, when strategic positions allowing the rapid capture of the RSK capital Knin were gained, and on the continued arming and training of the HV since the beginning of the Croatian War of Independence, when the RSK was created during the Serb Log Revolution and Yugoslav People's Army intervention. The operation itself followed an unsuccessful United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission and diplomatic efforts to settle the conflict.

The HV's and ARBiH's strategic success was a result of a series of improvements to the armies themselves, and crucial breakthroughs made in the ARSK positions that were subsequently exploited by the HV and the ARBiH. The attack was not immediately successful at all points, but seizing key positions led to the collapse of the ARSK command structure and overall defensive capability. The HV capture of Bosansko Grahovo, just before the operation, and the special police's advance to Gračac, made it nearly impossible to defend Knin. In Lika, two guard brigades quickly cut the ARSK-held area which lacked tactical depth and mobile reserve forces, and they isolated pockets of resistance, positioned a mobile force for a decisive northward thrust into the Karlovac Corps area of responsibility (AOR), and pushed ARSK towards Banovina. The defeat of the ARSK at Glina and Petrinja, after a tough defensive, defeated the ARSK Banija Corps as well since its reserve was pinned down by the ARBiH. The RSK relied on the Republika Srpska and Yugoslav militaries as its strategic reserve, but they did not intervene in the battle. The United States also played a role in the operation by directing Croatia to a military consultancy firm, Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), that signed a Pentagon licensed contract to advise, train and provide intelligence to the Croatian army.

The HV and the special police suffered 174–211 killed or missing, while the ARSK had 560 soldiers killed. Four UN peacekeepers were also killed. The HV captured 4,000 prisoners of war. The number of Serb civilian deaths is disputed—Croatia claims that 214 were killed, while Serbian sources cite 1,192 civilians killed or missing. The Croatian population had been years prior subjected to ethnic cleansing in the areas held by ARSK by rebel Serb forces, with an estimated 170,000–250,000 expelled and hundreds killed. During and after the offensive, around 150,000–200,000 Serbs of the area formerly held by the ARSK had fled and a variety of crimes were committed against some of the remaining civilians there by Croatian forces. The expelled Croatian Serbs were the largest refugee population in Europe prior to the 2022 Ukraine war.[4]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) later tried three Croatian generals charged with war crimes and partaking in a joint criminal enterprise designed to force the Serb population out of Croatia, although all three were ultimately acquitted and the tribunal refuted charges of a criminal enterprise. The ICTY concluded that Operation Storm was not aimed at ethnic persecution, as civilians had not been deliberately targeted. The ICTY stated that Croatian Army and Special Police committed a large number of crimes against the Serb population after the artillery assault, but that the state and military leadership was not responsible for their creation and organizing and that Croatia did not have the specific intent of displacing the country's Serb minority. However, Croatia adopted discriminatory measures to make it increasingly difficult for Serbs to return. Human Rights Watch reported that the vast majority of the abuses during the operation were committed by Croatian forces and that the abuses continued on a large scale for months afterwards, which included summary executions of Serb civilians and destruction of Serb property. In 2010, Serbia sued Croatia before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming that the offensive constituted a genocide. In 2015, the court ruled that the offensive was not genocidal and affirmed the ICTY's previous findings.

Background

[edit]

In August 1990, an insurgency known as the Log Revolution took place in Croatia centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[5] as well as in parts of the Lika, Kordun, and Banovina regions, and settlements in eastern Croatia with significant Serb populations.[6] The areas were subsequently formed into an internationally unrecognised proto-state, the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), and after it declared its intention to secede from Croatia and join the Republic of Serbia, the Government of the Republic of Croatia declared the RSK a rebellion.[7]

The conflict escalated by March 1991, resulting in the Croatian War of Independence.[8] In June 1991, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated.[9] A three-month moratorium on Croatia's and the RSK's declarations followed,[10] after which the decision came into effect on 8 October.[11] During this period, the RSK initiated a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Croat civilians. In 1991, 84,000 Croats fled Serbian-held territory.[12] Most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993. Hundreds of Croats were murdered and the total number of Croats and other non-Serbs who were expelled range from 170,000 according to the ICTY[13] and up to a quarter of a million people according to Human Rights Watch.[14] By November 1993, fewer than 400 ethnic Croats remained in the United Nations-protected area known as Sector South,[15] while a further 1,500 – 2,000 remained in Sector North.[16]

Croatian forces also engaged in ethnic cleansing against Serbs in eastern and western Slavonia and parts of the Krajina region, though on a more restricted scale and Serb victims numbered less than Croat victims of Serb forces.[17] In 1991, 70,000 Serbs were displaced from Croatian territory.[12] By October 1993, the UNHCR estimated that there was a total of 247,000 Croatian and other non-Serbian displaced persons coming from areas under the control of RSK and 254,000 Serbian displaced persons and refugees from the rest of Croatia, an estimated 87,000 of whom were inhabitants of the United Nations Protected Areas (UNPA's).[18]

During this time, Serbs living in Croatian towns, especially those near the front lines, were subjected to various forms of discrimination from being fired from jobs to having bombs planted under their cars or houses.[19] The UNHCR reported that in the Serb-controlled portions of the UNPA's, human rights abuses against Croats and non-Serbs were persistent. Some of the Krajina Serb "authorities" continued to be among the most egregious perpetrators of human rights abuses against the residual non-Serb population, as well as Serbs not in agreement with nationalistic policy. Human rights violations included killings, disappearances, beatings, harassment, forced resettlement, or exile, designed to ensure Serbian dominance of the areas.[18] In 1993, the UNHCR also reported a continued series of abuse against Serbs in Croatian government-held areas which included killings, disappearances, physical abuse, illegal detention, harassment and destruction of property.[18]

As the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian Police proved unable to cope with the situation, the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991. The ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (HV) in November.[20]

The establishment of the military of Croatia was hampered by a UN arms embargo introduced in September.[21] The final months of 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Battle of the Barracks,[22] the Siege of Dubrovnik,[23] and the Battle of Vukovar.[24]

In January 1992, an agreement to implement the Vance plan designed to stop the fighting was made by representatives of Croatia, the JNA and the UN.[25]

Ending the series of unsuccessful ceasefires, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed to Croatia to supervise and maintain the agreement.[26] A stalemate developed as the conflict evolved into static trench warfare, and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated.[25] Serbia continued to support the RSK,[27] but a series of HV advances restored small areas to Croatian control as the siege of Dubrovnik ended,[28] and Operation Maslenica resulted in minor tactical gains.[29]

In response to the HV successes, the Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina (ARSK) intermittently attacked a number of Croat towns and villages with artillery and missiles.[6][30][31]

As the JNA disengaged in Croatia, its personnel prepared to set up a new Bosnian Serb army, as Bosnian Serbs declared the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992, ahead of a 29 February – 1 March 1992 referendum on the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The referendum was later cited as a pretext for the Bosnian War.[32] Bosnian Serbs set up barricades in the capital, Sarajevo, and elsewhere on 1 March, and the next day the first fatalities of the war were recorded in Sarajevo and Doboj. In the final days of March, the Bosnian Serb army started shelling Bosanski Brod,[33] and on 4 April, Sarajevo was attacked.[34] By the end of the year, the Bosnian Serb army—renamed the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) after the Republika Srpska state was proclaimed—controlled about 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[35] That proportion would not change significantly over the next two years.[36] Although the war originally pitted Bosnian Serbs against non-Serbs in the country, it evolved into a three-sided conflict by the end of the year, as the Croat–Bosniak War started.[37] The RSK was supported to a limited extent by the Republika Srpska, which launched occasional air raids from Banja Luka and bombarded several cities in Croatia.[38][39]

Prelude

[edit]In November 1994, the Siege of Bihać, a theatre of operations in the Bosnian War, entered a critical stage as the VRS and the ARSK came close to capturing the town of Bihać from the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). It was a strategic area and,[40] since June 1993, Bihać had been one of six United Nations Safe Areas established in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[41]

The Clinton administration felt that its capture by Serb forces would intensify the war and lead to a humanitarian disaster greater than any other in the conflict to that point. Amongst the United States, France and the United Kingdom, division existed regarding how to protect the area.[40][42] The US called for airstrikes against the VRS, but the French and the British opposed them citing safety concerns and a desire to maintain the neutrality of French and British troops deployed as a part of the UNPROFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In turn, the US was unwilling to commit ground troops.[43]

On the other hand, the Europeans recognized that the US was free to propose military confrontation with the Serbs while relying on the European powers to block any such move,[44] since French President François Mitterrand discouraged any military intervention, greatly aiding the Serb war effort.[45] The French stance reversed after Jacques Chirac was elected president of France in May 1995,[46] pressuring the British to adopt a more aggressive approach as well.[47]

Denying Bihać to the Serbs was strategically important to Croatia,[48] and General Janko Bobetko, the Chief of the Croatian General Staff, considered the potential fall of Bihać to represent an end to Croatia's war effort.[49]

In March 1994, the Washington Agreement was signed,[49] ending the Croat–Bosniak War, and providing Croatia with US military advisors from Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI).[50][51] The US involvement reflected a new military strategy endorsed by Bill Clinton in February 1993.[52]

As the UN arms embargo was still in place, MPRI was hired ostensibly to prepare the HV for participation in the NATO Partnership for Peace programme. MPRI trained HV officers and personnel for 14 weeks from January to April 1995. It has also been speculated in several sources,[50] including an article in The New York Times by Leslie Wayne and in various Serbian media reports,[53][54] that MPRI may also have provided doctrinal advice, scenario planning and US government satellite intelligence to Croatia,[50] although MPRI,[55] American and Croatian officials denied such claims.[56][57] In November 1994, the United States unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina,[58] in effect allowing the HV to supply itself as arms shipments flowed through Croatia.[59]

The Washington Agreement also resulted in a series of meetings between Croatian and US government and military officials in Zagreb and Washington, D.C. On 29 November 1994, the Croatian representatives proposed to attack Serb-held territory from Livno in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in order to draw away part of the force besieging Bihać and to prevent the town's capture by the Serbs. As the US officials gave no response to the proposal, the Croatian General Staff ordered Operation Winter '94 the same day, to be carried out by the HV and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO)—the main military force of Herzeg-Bosnia. In addition to contributing to the defence of Bihać, the attack shifted the HV's and HVO's line of contact closer to the RSK's supply routes.[49]

In 1994, the United States, Russia, the European Union (EU) and the UN sought to replace the Vance plan, which brought in the UNPROFOR. They formulated the Z-4 Plan giving Serb-majority areas in Croatia substantial autonomy.[60]

After numerous and frequently uncoordinated changes to the proposed plan, including leaking of its draft elements to the press in October, the Z-4 Plan was presented on 30 January 1995. Neither Croatia nor the RSK liked the plan. Croatia was concerned that the RSK might accept it, but Tuđman realised that Milošević, who would ultimately make the decision for the RSK,[61] would not accept the plan for fear that it would set a precedent for a political settlement in Kosovo—allowing Croatia to accept the plan with little possibility for it to be implemented.[60] The RSK refused to receive, let alone accept, the plan.[62]

In December 1994, Croatia and the RSK made an economic agreement to restore road and rail links, water and gas supplies, and use of a part of the Adria oil pipeline. Even though some of the agreement was never implemented,[63] a section of the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway passing through RSK territory near Okučani and the pipeline were both opened. Following a deadly incident that occurred in late April 1995 on the recently opened motorway,[64] Croatia reclaimed all of the RSK's territory in western Slavonia during Operation Flash,[65] taking full control of the territory by 4 May, three days after the battle began. In response, the ARSK attacked Zagreb using M-87 Orkan missiles with cluster munitions.[66] Subsequently, Milošević sent a senior Yugoslav Army officer to command the ARSK, along with arms, field officers and thousands of Serbs born in the RSK area who had been forcibly conscripted by the ARSK.[67]

On 17 July, the ARSK and the VRS started a fresh effort to capture Bihać by expanding on gains made during Operation Spider. The move provided the HV with a chance to extend their territorial gains from Operation Winter '94 by advancing from the Livno valley. On 22 July, Tuđman and Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović signed the Split Agreement for mutual defence, permitting the large-scale deployment of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The HV and HVO responded quickly through Operation Summer '95 (Croatian: Ljeto '95), capturing Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč on 28–29 July.[68] The attack drew some ARSK units away from Bihać,[68][69] but not as many as expected. However, it put the HV in an excellent position,[70] as it isolated Knin from the Republika Srpska, as well as Yugoslavia.[71]

In late July and early August, there were two more attempts at resurrecting the Z-4 Plan and the 1994 economic agreement. Talks proposed on 28 July were ignored by the RSK, and last-ditch talks were held in Geneva on 3 August. These quickly broke down as Croatia and the RSK rejected a compromise proposed by Thorvald Stoltenberg, a Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General, essentially calling for further negotiations at a later date. In addition, the RSK dismissed a set of Croatian demands, including to disarm, and failed to endorse the Z-4 Plan once again. The talks were used by Croatia to prepare diplomatic ground for the imminent Operation Storm,[72] whose planning was completed during the Brijuni Islands meeting between Tuđman and military commanders on 31 July.[73]

The HV initiated large-scale mobilization in late July, soon after General Zvonimir Červenko became its new Chief of General Staff on 15 July.[74] In 2005, the Croatian weekly magazine Nacional reported that the U.S. had been actively involved in the preparation, monitoring and initiation of Operation Storm, that the green light from President Clinton was passed on by the US military attache in Zagreb, and the operations were transmitted in real time to Pentagon.[75]

Order of battle

[edit]

HV, ARSK

In Bosnia and Herzegovina:

HV/HVO, VRS/ARSK, ARBiH/HVO, APWB

The HV operational plan was set out in four separate parts, designated Storm-1 through 4, which were allocated to various corps based upon their individual areas of responsibility (AORs). Each plan was scheduled to take between four and five days.[74] The forces that the HV allocated to attack the RSK were organised into five army corps: Split, Gospić, Karlovac, Zagreb and Bjelovar Corps.[76] A sixth zone was assigned to the Croatian special police inside the Split Corps AOR,[77] near the boundary with the Gospić Corps.[78] The HV Split Corps, located in the far south of the theatre of operations and commanded by Lieutenant General Ante Gotovina, was assigned the Storm-4 plan, which was the primary component of Operation Storm.[77] The Split Corps issued orders for the battle using the name Kozjak-95 instead, which was not an unusual practice.[79] The 30,000-strong Split Corps was opposed by the 10,000-strong ARSK 7th North Dalmatia Corps,[77] headquartered in Knin and commanded by Major General Slobodan Kovačević.[78] The 3,100-strong special police, deployed to the Velebit Mountain on the left flank of the Split Corps, were directly subordinated to the HV General Staff commanded by the Lieutenant General Mladen Markač.[80]

The 25,000-strong HV Gospić Corps was assigned the Storm-3 component of the operation,[81] to the left of the special police zone. It was commanded by Brigadier Mirko Norac, and opposed by the ARSK 15th Lika Corps, headquartered in Korenica and commanded by Major General Stevan Ševo.[82] The Lika Corps, consisting of about 6,000 troops, was sandwiched between the HV Gospić Corps and the ARBiH in the Bihać pocket in ARSK rear, forming a wide but a very shallow area. The ARBiH 5th Corps deployed about 2,000 troops in the zone. The Gospić Corps, assigned a 150-kilometre (93 mi) section of the front, was tasked with cutting the RSK in half and linking up with the ARBiH, while the ARBiH was tasked with pinning down ARSK forces that were in contact with the Bihać pocket.[81]

The HV Karlovac Corps, commanded by Major General Miljenko Crnjac, on the left flank of the Gospić Corps, covered the area extending from Ogulin to Karlovac, including Kordun,[83] and executed the Storm-2 plan. The corps was composed of 15,000 troops and was tasked with pinning down the ARSK forces in the area to protect the flanks of the Zagreb and Gospić Corps.[84] It had a forward command post in Ogulin and was opposed by the ARSK 21st Kordun Corps headquartered at Petrova Gora,[83] consisting of 4,000 troops in the AOR (one of its brigades was facing the Zagreb Corps).[84] Initially, the 21st Kordun Corps was commanded by Colonel Veljko Bosanac, but he was replaced by Colonel Čedo Bulat during the evening of 5 August. In addition, the bulk of the ARSK Special Units Corps was present in the area, commanded by Major General Milorad Stupar.[83] ARSK Special Units Corps was 5,000-strong, largely facing the Bihać pocket at the onset of Operation Storm. The ARSK armour and artillery in the AOR outnumbered that of the HV.[84]

The HV Zagreb Corps, assigned the Storm-1 plan, initially commanded by Major General Ivan Basarac, on the left flank of the Karlovac Corps, was deployed on three main axes of attack—towards Glina, Petrinja and Hrvatska Kostajnica. It was opposed by the ARSK 39th Banija Corps, headquartered in Glina and commanded by Major General Slobodan Tarbuk.[85] The Zagreb Corps was tasked with bypassing Petrinja to neutralize ARSK artillery and missiles potentially targeting Croatian cities, making a secondary thrust from Sunja towards Hrvatska Kostajnica. Their secondary mission was compromised when a battalion of the special police and the 81st Guards Battalion planned to spearhead the advance were deployed elsewhere forcing modifications to the plan. The Zagreb Corps was composed of 30,000 troops, while the ARSK had 9,000 facing them and about 1,000 ARBiH troops in the Bihać pocket to their rear. At the start of Operation Storm, about 3,500 ARSK troops were in contact with the ARBiH.[86] HV Bjelovar Corps, on the left flank of the Zagreb Corps, covering the area along the Una River, had a forward command post in Novska. The corps was commanded by Major General Luka Džanko. Opposite the Bjelovar Corps was a part of the ARSK Banija Corps. The Bjelovar Corps was included in the attack on 2 August and were therefore not issued a separate operations plan.[87]

The ARSK divided its forces in the area in two, subordinating the North Dalmatia and Lika Corps to the ARSK General Staff, and grouping the rest into the Kordun Operational Group commanded by Lieutenant Colonel General Mile Novaković. Territorially, the division corresponded to the North and South sectors of the UN protected areas.[88]

Estimates of the total number of troops deployed by the belligerents vary considerably. Croatian forces have been estimated from under 100,000 to 150,000,[65][89] but most sources put the figure at about 130,000 troops.[90][91] ARSK troop strength in the Sectors North and South was estimated by the HV prior to Operation Storm at approximately 43,000.[92] More detailed HV estimates of the manpower by individual ARSK corps indicated 34,000 soldiers,[93] while Serb sources quote 27,000 troops.[94] The discrepancy is usually reflected in literature as an estimate of about 30,000 ARSK troops.[90] The ARBiH deployed approximately 3,000 troops against the ARSK positions near Bihać.[84] In late 1994, the Fikret Abdić-led Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia (APWB)—a sliver of land northwest of Bihać between its ally RSK and the pocket—commanded 4,000–5,000 soldiers who were deployed south of Velika Kladuša against the ARBiH force.[95]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Split Corps | 4th Guards Brigade | In the Bosansko Grahovo area |

| 7th Guards Brigade | ||

| 81st Guards Battalion | In the Glamoč area | |

| 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | A part of the 1st Croatian Guards Corps; Held in reserve in the Bosansko Grahovo area | |

| 6th Home Guard Regiment | In the Sinj area | |

| 126th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 144th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 142nd Home Guard Regiment | In the Šibenik area | |

| 15th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 113th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade | In the Zadar area | |

| 112th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 7th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 134th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 10th Artillery-Rocket Regiment of the HVO | Supporting the Split Corps | |

| 14th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 20th Artillery (Howitzer) Battalion | ||

| Elements of the artillery battalion of the 5th Guards Brigade | ||

| 11th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| Gospić Corps | 138th Home Guard Regiment | In the Saborsko area |

| 133rd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 9th Guards Brigade | Without its 2nd Battalion, in the Gospić area | |

| 118th Home Guard Regiment | In the Gospić area | |

| 111th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 12th Artillery Battalion | Supporting the Gospić Corps | |

| 1st Guards Brigade | Directly subordinated to the HV General Staff; Temporarily assigned to the Gospić Corps from 4–6 August | |

| Karlovac Corps | 104th Infantry Brigade | In the Karlovac area |

| 110th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 137th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 14th Home Guard Regiment | In the Ogulin area | |

| 143rd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 99th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 1 battalion of the 148th Infantry Brigade | In reserve | |

| 7th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | Supporting the Karlovac Corps | |

| 13th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| 33rd Engineer Brigade | ||

| Zagreb Corps | 17th Home Guard Regiment | In the Sunja area |

| 103rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 151st Infantry Brigade | ||

| 2nd Guards Brigade | In the Petrinja area | |

| 57th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 12th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 20th Home Guard Regiment | In the Petrinja and Glina areas | |

| 153rd Infantry Brigade | In the Glina area | |

| 202nd Artillery-Rocket Brigade | Supporting the Zagreb Corps | |

| 67th Military Police Battalion | ||

| 252nd Independent Signals Company | ||

| 502nd Mechanized NBC Warfare Company | ||

| 1 battalion of the 33rd Engineer Brigade | ||

| 31st Engineer Battalion | ||

| 36th Engineer-Pontoon Battalion | ||

| 1st Riverine Corps | ||

| 6th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 8th Howitzer Artillery Battalion (203mm) | ||

| 1 battalion of the 16th Artillery-Rocket Brigade | ||

| 5th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| 1 battalion of the 15th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Brigade | ||

| Bjelovar Corps | 125th Home Guard Regiment | In the Jasenovac area |

| 52nd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 34th Engineer Battalion | ||

| 24th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 18th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 121st Home Guard Regiment | In the Okučani area |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| North Dalmatia Corps | 75th Motorized Brigade | Opposite the Split Corps |

| 92nd Motorized Brigade | ||

| 1st Light Brigade | ||

| 4th Light Brigade | ||

| 2nd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 3rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 7th Mixed Artillery Regiment | ||

| 7th Mixed Antitank Artillery Regiment | ||

| 7th Light Artillery-Rocket Regiment | ||

| Special Units Corps | 2nd Guards Brigade | |

| Lika Corps | 9th Motorized Brigade | Opposite the Gospić Corps |

| 18th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 50th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 103rd Light Brigade | ||

| 37th Infantry Battalion | ||

| 15th Mixed Artillery Battalion | ||

| 15th Mixed Antitank Artillery Battalion | ||

| 70th Infantry Brigade | Opposite Gospić and Karlovac Corps | |

| Kordun Corps | 11th Infantry Brigade | Opposite the Karlovac Corps |

| 13th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 19th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 21st Border Squadron | ||

| 21st Reconnaissance Squadron | ||

| 21st Mixed Artillery Squadron | ||

| 75th Mixed Antitank Artillery Squadron | ||

| 75th Engineer Battalion | ||

| Special Units Corps | Missing its 2nd Guards Brigade; Opposite the Karlovac Corps | |

| Banija Corps | 24th Infantry Brigade | Opposite the Zagreb Corps |

| 33rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 31st Motorized Brigade | ||

| ARSK General Staff Artillery Group | ||

| 26th Infantry Brigade | Opposite Zagreb and Bjelovar Corps | |

| Army of Republika Srpska | 11th Brigade | In the Republika Srpska, on the right flank of the RSK Banija Corps |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Corps | 501st Mountain Brigade | Opposite the Lika Corps |

| 502nd Mountain Brigade | ||

| 505th Mountain Brigade | Opposite the Banija Corps | |

| 511th Mountain Brigade |

Operation timeline

[edit]4 August 1995

[edit]Operation Storm started at 5 a.m. on 4 August 1995 when coordinated attacks were executed by reconnaissance and sabotage detachments in concert with Croatian Air Force (CAF) air strikes aimed at disrupting ARSK command, control, and communications.[97] UN peacekeepers, known as United Nations Confidence Restoration Operation (UNCRO),[98] were notified three hours in advance of the attack when Tuđman's chief of staff, Hrvoje Šarinić, telephoned UNCRO commander, French Army General Bernard Janvier. In addition, each HV corps notified the UNCRO sector in its path of the attack, requesting written confirmations of receipt of the information. The UNCRO relayed the information to the RSK,[99] confirming the warnings RSK received from the Yugoslav Army General Staff the previous day.[100]

Sector South

[edit]

In the Split Corps AOR, at 5 a.m. the 7th Guards Brigade advanced south from Bosansko Grahovo towards the high ground ahead of Knin after a period of artillery preparation. Moving against the ARSK 3rd Battlegroup, consisting of elements of the North Dalmatian Corps and RSK police, the 7th Guards achieved its objectives for the day and allowed the 4th Guards Brigade to attack. The HV Sinj Operational Group (OG), on the left flank of the two brigades, joined the attack and the 126th Home Guard Regiment captured Uništa, gaining control of the area overlooking the Sinj–Knin road. The 144th Brigade and the 6th Home Guard Regiment also pushed ARSK forces back. The Šibenik OG units faced the ARSK 75th Motorized Brigade and a part of the 2nd Infantry Brigade of the ARSK North Dalmatian Corps. There, the 142nd and the 15th Home Guard Regiments made minor progress in the area between Krka and Drniš, while the 113th Infantry Brigade made a slightly greater advance on their left flank, to Čista Velika. In the Zadar OG area, the 134th Home Guard Regiment (without its 2nd Battalion) failed to advance, while the 7th Home Guard Regiment and the 112th HV Brigade gained little ground against the ARSK 92nd Motorized and 3rd Infantry Brigades at Benkovac. On the Velebit, the 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade, reinforced with a company from the 7th Home Guard Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion of the 134th Home Guard Regiment met stiff resistance but advanced sufficiently to secure use of the Obrovac–Sveti Rok road. At 4:45 p.m., a decision to evacuate the population in the Northern Dalmatia and Lika areas was made by RSK President Milan Martić.[101][102] According to RSK Major General Milisav Sekulić, Martić ordered the evacuation hoping to coax Milošević and the international community to help the RSK.[103] Nonetheless, the evacuation was extended the whole sectors North and South, except Kordun region.[104] In the evening the ARSK Main Staff moved from Knin to Srb,[101] about 35 kilometres (22 miles) to the northwest.[105]

At 5 a.m., Croatian special police advanced to the Mali Alan pass on the Velebit, encountering strong resistance from the ARSK Lika Corps' 4th Light Brigade and elements of the 9th Motorized Brigade. The pass was captured at 1 p.m., and Sveti Rok village was captured at about 5 p.m. The special police advanced further beyond Mali Alan, meeting more resistance at 9 p.m. and then bivouacking until 5 a.m. The ARSK 9th Motorized Brigade withdrew to Udbina after being forced out of its positions on the Velebit. In the morning, the special police captured Lovinac, Gračac and Medak.[106]

In the Gospić Corps AOR, the 138th Home Guard Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade began an eastward attack in the Mala Kapela area in the morning, meeting heavy resistance from the ARSK 70th Infantry Brigade. The rest of the 1st Guards joined in around midnight. The 133rd Home Guard Regiment attacked east of Otočac, towards Vrhovine, attempting to encircle the ARSK 50th Infantry Brigade and elements of the ARSK 103rd Infantry Brigade in a pincer movement. Even though the regiment advanced, it failed to achieve its objective for the day. On the regiment's right flank, the HV 128th Brigade advanced together with the 3rd Battalion of the 8th Home Guard Regiment and cut through the Vrhovine–Korenica road. The rest of the 9th Guards Brigade, the bulk of the HV 118th Home Guard Regiment and the 111th Infantry Brigade advanced east from Gospić and Lički Osik, coming up against very strong resistance from the ARSK 18th Infantry Brigade. As a result of these setbacks, the Gospić Corps ended the day short of the objectives it had been given.[107]

Sector North

[edit]In the Ogulin area of the HV Karlovac Corps AOR, the 99th Brigade, reinforced by the 143rd Home Guard Regiment's Saborsko Company, moved towards Plaški at 5 a.m., but the force was stopped and turned back in disarray by 6 p.m. The 143rd Home Guard Regiment advanced from Josipdol towards Plaški, encountering minefields and strong ARSK resistance. Its elements connected with the 14th Home Guard Regiment, advancing through Barilović towards Slunj. Near the city of Karlovac, the 137th Home Guard Regiment deployed four reconnaissance groups around midnight of 3–4 August, followed by artillery preparation and crossing of the Korana River at 5 a.m. The advance was fiercely resisted by the ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade, but the bridgehead was stable by the end of the day. The 110th Home Guard Regiment, reinforced by a company of the 137th Home Guard Regiment, advanced east to the road leading south from Karlovac to Vojnić and Slunj, where it met heavy resistance and suffered more casualties to landmines, demoralizing the unit and preventing its further advance. In addition, the attached company of the 137th Home Guard Regiment and the 104th Brigade failed to secure the regiment's flanks. The 104th Brigade tried to cross the Kupa River at 5 a.m., but failed and fell back to its starting position by 8 a.m., at which time it was shifted to the bridgehead established by the 110th Home Guard Regiment. A company of the 99th Brigade was attached to the 143rd Home Guard Regiment for operations the next day, and a 250-strong battlegroup was removed from the brigade and subordinated to the Karlovac Corps directly.[108]

In the Zagreb Corps area, the HV moved across the Kupa River at two points towards Glina—in and near Pokupsko, using the 20th Home Guard Regiment and the 153rd Brigade. Both crossings established bridgeheads, although the bulk of the units were forced to retreat as the ARSK counter-attacked—only a battalion of the 153rd Brigade and elements of the 20th Home Guard Regiment held their ground. The crossings prompted the ARSK General Staff to order the 2nd Armoured Brigade of the Special Units Corps to move from Slunj to the bridgeheads,[109] as the HV advance threatened a vital road in Glina.[84] The HV 2nd Guards Brigade and the 12th Home Guard Regiment were tasked with the quick capture of Petrinja from the ARSK 31st Motorized Brigade in a pincer movement.[109] The original plan, involving thrusts six to seven kilometres (3.7 to 4.3 miles) south of Petrinja, was amended by Basarac to a direct assault on the city.[77] On the right flank, the regiment was soon stopped by minefields and forced to retreat, while the bulk of the 2nd Guards Brigade advanced until it wavered following the loss of a company commander and five soldiers. The rest of the 2nd Guards Brigade—reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, elements of the 12th Home Guard Regiment, the 5th Antitank Artillery Battalion and the 31st Engineers Battalion—formed Tactical Group 2 (TG2) operating on the left flank of the attack. TG2 advanced from Mošćenica, a short distance from Petrinja, but was stopped after the 2nd Battalion's commander and six soldiers were killed. The ARSK 31st Motorized Brigade also panicked but managed to stabilize its defences as it received reinforcements. The HV 57th Brigade advanced south of Petrinja, intent on reaching the Petrinja–Hrvatska Kostajnica road, but ran into a minefield where the brigade commander was killed, while the 101st Brigade to its rear suffered heavy artillery fire and casualties. In the Sunja area, the 17th Home Guard Regiment and a company of the 151st Brigade unsuccessfully attacked the ARSK 26th Infantry Brigade. Later that day, a separate attack by the rest of the 151st Brigade also failed. The HV 103rd Brigade advanced to the Sunja–Sisak railroad, but had to retreat under heavy fire. The Zagreb Corps failed to meet any objective of the first day. This was attributed to inadequate manpower and as a result the corps requested the mobilization of the 102nd Brigade and the 1st and 21st Home Guard Regiments. The 2nd Guards Brigade was reinforced by the 1st Battalion of the 149th Brigade previously held in reserve in Ivanić Grad.[109]

In the Bjelovar Corps AOR, two battalions of the 125th Home Guard Regiment crossed the Sava River near Jasenovac, secured a bridgehead for trailing HV units and advanced towards Hrvatska Dubica. The two battalions were followed by an additional company of the same regiment, a battalion of the 52nd Home Guard Regiment, the 265th Reconnaissance Company and finally the 24th Home Guard Regiment battlegroup. A reconnaissance platoon of the 52nd Home Guard Regiment crossed the Sava River into the Republika Srpska, established a bridgehead for two infantry companies and subsequently demolished the Bosanska Dubica–Gradiška road before returning to Croatian soil. The Bjelovar Corps units reached the outskirts of Hrvatska Dubica before nightfall. That night, the town of Hrvatska Dubica was abandoned by the ARSK troops and the civilian population. They fled south across the Sava River into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[110]

5 August 1995

[edit]Sector South

[edit]

The HV did not advance towards Knin during the night of 4/5 August when the ARSK General Staff ordered a battalion of the 75th Motorized Brigade to stage themselves north of Knin. The ARSK North Dalmatian Corps became increasingly uncoordinated as the HV 4th Guards Brigade advanced south towards Knin, protecting the right flank of the 7th Guards Brigade. The latter met little resistance and entered the town at about 11 a.m. Lieutenant General Ivan Čermak was appointed commander of the newly established HV Knin Corps. Sinj OG completed its objectives, capturing Kozjak and Vrlika, and meeting little resistance as the ARSK 1st Light Brigade disintegrated, retreating to Knin and later to Lika. By 8 p.m., Šibenik OG units advanced to Poličnik (113th Brigade), Đevrske (15th Home Guard Regiment), and captured Drniš (142nd Home Guard Regiment), while the ARSK 75th Motorized Brigade retreated towards Srb and Bosanski Petrovac together with the 3rd Infantry and the 92nd Motorized Brigades, leaving the Zadar OG units with little opposition. The 7th Home Guard Regiment captured Benkovac, while the 112th Brigade entered Smilčić and elements of the 9th Guards Brigade reached Obrovac.[111]

The 138th Home Guard Regiment and the 1st Guards Brigade advanced to Lička Jasenica, the latter pressing their attack further towards Saborsko, with the 2nd Battalion of the HV 119th Brigade reaching the area in the evening. The HV reinforced the 133rd Home Guard Regiment with a battalion of the 150th Brigade enabling the regiment to achieve its objectives of the previous day, partially encircling the ARSK force in Vrhovine. The 154th Home Guard Regiment was mobilized and deployed to the Ličko Lešće area. The 9th Guards Brigade (without its 2nd Battalion) advanced towards Udbina Air Base, where ARSK forces started to evacuate. The 111th Brigade and the 118th Home Guard Regiment also made small advances, linking up behind ARSK lines.[112]

Sector North

[edit]The 143rd Home Guard Regiment advanced towards Plaški, capturing it that evening, while the 14th Home Guard Regiment captured Primišlje, 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) northwest of Slunj. At 0:30 a.m., the ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade and a company of the 19th Infantry Brigade counter-attacked at the Korana bridgehead, causing the bulk of the 137th Home Guard Regiment to panic and flee across the river. A single platoon of the regiment remained but the ARSK troops did not exploit the opportunity to destroy the bridgehead. In the morning, the regiment reoccupied the bridgehead, reinforced by a 350-strong battlegroup drawn from the 104th Brigade (including a tank platoon and multiple rocket launchers), and a company of the 148th Brigade from the Karlovac Corps operational reserve. The regiment and the battlegroup managed to extend the bridgehead towards the Karlovac–Slunj road. The 110th Home Guard Regiment attacked again south of Karlovac, but was repelled by prepared ARSK defences. That night, the Karlovac Corps decided to move elements of the 110th Home Guard Regiment and the 104th Brigade to the Korana bridgehead, while the ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade retreated to the right bank of Korana in an area extending about 30 kilometres (19 miles) north from Slunj.[113]

The Zagreb Corps made little or no progress on day two of the battle. Part of the 2nd Guards Brigade was ordered to drive towards Glina with the 20th Home Guards Regiment making a modest advance, while the 153rd Brigade abandoned its bridgehead. In the area of Petrinja, the HV advanced gradually only to be pushed back in some areas by an ARSK counter-attack. The results were reversed at significant cost by a renewed push by the 2nd Guards Brigade. The Zagreb Corps commander was replaced by Lieutenant General Petar Stipetić on orders from President Tuđman. The HV reassigned the 102nd Brigade to drive to Glina, and the 57th Brigade was reinforced with the 2nd Battalion of the 149th Brigade. The 145th Brigade was moved from Popovača to the Sunja area, where the 17th Home Guard Regiment and the 151st Brigade made minor advances into the ARSK-held area.[114]

In the Bjelovar Corps AOR, Hrvatska Dubica was captured by the 52nd and the 24th Home Guard Regiments advancing from the east and the 125th Home Guard Regiment approaching from the north. The 125th Home Guard Regiment garrisoned the town, while the 52nd Home Guard Regiment moved northwest towards expected Zagreb Corps positions, but the Zagreb Corps' delays prevented any link-up. The 24th Home Guard Regiment advanced about four kilometres (2.5 miles) towards Hrvatska Kostajnica when it was stopped by ARSK troops. In response, the Corps called in a battalion and a reconnaissance platoon of the 121st Home Guard Regiment from Nova Gradiška to aid the push to the town.[115] The ARBiH 505th and 511th Mountain Brigades advanced north to Dvor and engaged the ARSK 33rd Infantry Brigade—the only reserve unit of the Banija Corps.[116]

6 August 1995

[edit]

On 6 August, the HV conducted mopping-up operations in the areas around Obrovac, Benkovac, Drniš and Vrlika, as President Tuđman visited Knin.[117] After securing their objectives on or near Velebit, the special police was deployed on foot behind ARSK lines to hinder movement of ARSK troops there, capturing strategic intersections in the villages of Bruvno at 7 a.m. and Otrić at 11 a.m.[118]

At midnight, elements of the ARBiH 501st and 502nd Mountain Brigades advanced west from Bihać against a skeleton force of the ARSK Lika Corps that had been left behind since the beginning of the battle. The 501st moved about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) into Croatian territory, to Ličko Petrovo Selo and Plitvice Lakes by 8 a.m. The 502nd captured an ARSK radar and communications facility on Plješivica Mountain, and proceeded towards Korenica where it was stopped by the ARSK units. The HV 1st Guards Brigade reached Rakovica and linked up with the Bosnia-Herzegovina 5th Corps in the area of Drežnik Grad by 11 a.m.[119] It was supported by the 119th Brigade and a battalion of the 154th Home Guard Regiment deployed in the Tržačka Raštela and Ličko Petrovo Selo areas.[120] In the afternoon, a link-up ceremony was held for the media in Tržačka Raštela.[121] The 138th Home Guard Regiment completely encircled Vrhovine, which was captured by the end of the day by the 8th and the 133rd Home Guard Regiments, reinforced with a battalion of the 150th Brigade. The HV 128th Brigade entered Korenica while the 9th Guards Brigade continued towards Udbina.[120]

The 143rd Home Guard Regiment advanced to Broćanac where it connected with the 1st Guards Brigade. From there the regiment continued towards Slunj, accompanied by elements of the 1st Guards Brigade and the 14th Home Guard Regiment, capturing the town at 3 p.m. The advance of the 14th Home Guard Regiment was supported by the 148th Brigade guarding its flanks. The ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade retreated from Slunj, together with the civilian population, moving north towards Topusko. An attack by the 137th Home Guard Regiment, and the elements of various units reinforcing it, extended the bridgehead and connected it with the 14th Home Guard Regiment in Veljun, 18 kilometres (11 miles) north of Slunj. The rest of the 149th Brigade (without the 1st Battalion) was reassigned from the Zagreb Corps to the Karlovac Corps to reinforce the 137th Home Guard Regiment.[122] At 11 a.m., an agreement was reached between the ARSK and civilian authorities in Glina and Vrginmost, securing the evacuation of civilians from the area.[123] The ARBiH 502nd Mountain Brigade also moved north, flanking the APWB capital of Velika Kladuša from the west, and capturing the town by the end of the day.[124]

The TG2 advanced to Petrinja at about 7 a.m. after a heavy artillery preparation. The 12th Home Guard Regiment entered the city from the west and was subsequently assigned to garrison Petrinja and its surrounding area. After the loss of Petrinja to the HV, the bulk of the ARSK Banija Corps started to retreat towards Dvor. The HV 57th Brigade advanced against light resistance and took control of the Petrinja–Hrvatska Kostajnica road. During the night of 6/7 August, the 20th Home Guard Regiment, supported by Croatian police and elements of the 153rd Brigade, captured Glina despite strong resistance. The 153rd Brigade then took positions that allowed the advance to continue towards the village of Maja in coordination with the 2nd Guards Brigade, which drove south from Petrinja towards Zrinska gora conducting mop-up operations. The 140th Home Guard Regiment flanked the 2nd Guards Brigade on the northern slope of Zrinska Gora, while the 57th Brigade captured Umetić. The 103rd and the 151st Brigades, and the 17th Home Guard Regiment, advanced towards Hrvatska Kostajnica, with the addition of a battalion of the HV 145th Brigade which would arrive that afternoon. Around noon, the 151st Brigade connected with the Bjelovar Corps units on the Sunja–Hrvatska Dubica road. They were assigned to secure roads in the area afterwards.[125]

By capturing Glina, the HV trapped the bulk of the ARSK Kordun Corps and about 35,000 evacuating civilians in the area of Topusko, prompting its commander to request UNCRO protection. The 1st Guards Brigade, approaching Topusko from Vojnić, received orders to engage the ARSK Kordun Corps, but the orders were cancelled at midnight by the chief of the HV General Staff. Instead, the Zagreb Corps was instructed to prepare a brigade-strength unit to escort unarmed persons and ARSK officers and non-commissioned officers with side arms to Dvor and allow them to cross into Bosnia and Herzegovina. Based on information obtained from UN troops, it was believed that the ARSK forces in Banovina were about to surrender.[126]

A battalion of the 121st Home Guard Regiment entered Hrvatska Kostajnica, while the 24th Home Guard Regiment battlegroup secured the national border behind them. The 52nd Home Guard Regiment connected with the Zagreb Corps and then turned south to the town, reaching it that evening. The capture of Hrvatska Kostajnica marked the fulfilment of all of the Bjelovar Corps' objectives.[127]

7 August 1995

[edit]The 1st Croatian Guards Brigade (1. hrvatski gardijski zdrug - HGZ) arrived in the Knin area to connect with elements of the 4th, 7th and 9th Guards Brigades, tasked with a northward advance the next day. The Split Corps command moved to Knin as well.[128] The Croatian special police proceeded to Gornji Lapac and Donji Lapac arriving by 2 p.m. and completing the boundary between the Gospić and Split Corps AORs. The Croatian special police also made contact with the 4th Guards Brigade in Otrić and the Gospić Corps units in Udbina by 3 p.m. By 7 p.m., a battalion of the special police reached the border near Kulen Vakuf, securing the area.[129]

In the morning, the 9th Guards Brigade (without its 2nd Battalion) captured Udbina, where it connected with the 154th Home Guard Regiment, approaching from the opposite side of the Krbava Polje (Croatian: Polje or karst field). By the end of the day, Operation Storm objectives assigned to the Gospić Corps were completed.[130]

A forward command post of the HV General Staff was moved from Ogulin to Slunj, and it assumed direct command of the 1st Guards Brigade, the 14th Home Guard Regiment and the 99th Brigade. The 14th Home Guard Regiment secured the Slunj area and deployed to the left bank of Korana to connect with the advancing Karlovac special police. Elements of the regiment and the 99th Brigade secured the national border in the area. The 1st Guards Brigade advanced towards Kordun, as the Karlovac Corps reoriented its main axis of attack. The 110th Home Guard Regiment and elements of the 104th Brigade reached a largely deserted Vojnić in early afternoon, followed by the 1st Guards Brigade, the 143rd Home Guard Brigade and the 137th Home Guard Regiment. Other HV units joined them by evening.[131]

The 2nd Guards Brigade advanced from Maja towards Dvor, but was stopped approximately 25 kilometres (16 miles) short by ARSK units protecting the withdrawal of the ARSK and civilians towards the town. Elements of the brigade performed mopping-up operations in the area. The ARSK 33rd Infantry Brigade held the road bridge in Dvor that connected the ARSK and the Republika Srpska across the Una River. The brigade was overwhelmed by the ARBiH 5th Corps, and it retreated south of Una, as the ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade and the civilians from Kordun were reaching Dvor. Elements of the 17th Home Guard Regiment and the HV 145th and 151st Brigades reached Dvor via Hrvatska Kostajnica and came into contact with the ARSK 13th Infantry Brigade and elements of the ARSK 24th Infantry and 2nd Armoured Brigades, who had retreated from Glina.[124][132] As the expected surrender of the ARSK Kordun Corps did not materialize, the HV was ordered to reengage.[126] Despite major pockets of resistance, Croatia's defence minister, Gojko Šušak, declared major operations over at 6 p.m.,[124] 84 hours after the battle had started.[133]

8–14 August 1995

[edit]On 8 August, the 4th and the 7th Guards Brigades, the 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade and the 1st HGZ advanced north to Lička Kaldrma and the border of Bosnia and Herzegovina, eliminating the last major pocket of ARSK resistance in Donji Lapac and the Srb area by 8 p.m.[134] and achieving all of Split Corps' objectives for Operation Storm.[128] After the capture of Vojnić, the bulk of the Karlovac Corps units were tasked with mopping up operations in their AOR.[135] Elements of the 2nd Guards Brigade reached the Croatian border southwest of Dvor, where fighting for full control of the town was in progress, and connected with the ARBiH 5th Corps.[136]

As Tuđman ordered the cessation of military operations that afternoon, the ARSK Kordun Corps accepted surrender. Negotiations of the terms of surrender were held the same day at 1:20 p.m. at the Ukrainian UNCRO troops command post in Glina, and the surrender document was signed at 2 p.m. in Topusko. Croatia was represented by Lieutenant General Stipetić, while the RSK was represented by Bulat, commander of the ARSK Kordun Corps, and Interior Minister Tošo Pajić. The terms of surrender specified the handover of weapons, except officers' side arms, on the following day, and the evacuation of persons from Topusko via Glina, Sisak, and the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway to Serbia, protected by the Croatian military and civilian police.[137]

On 9 August, the special police surrendered their positions to the HV, after covering more than 150 kilometres (93 miles) on foot in four days.[129] The 1st Guards Brigade, followed by other HV units, entered Vrginmost. The 110th and the 143rd Home Guard Regiments conducted mopping up operations around Vrginmost and Lasinja. The 137th Home Guard Regiment conducted mopping up operations in the Vojnić area and the 14th Home Guard Regiment did the same in the Slunj, Cetingrad, and Rakovica areas.[138] The HV secured Dvor late in the evening, shortly after the civilians finished evacuating. Numerous HV Home Guard units were later tasked with further mopping up operations.[136]

On 10 August, the HV 57th Brigade reached the Croatian border south of Gvozdansko, while elements of the 2nd Guards Brigade reached Dvor and the 12th Home Guard Regiment captured Matijevići, just to the south of Dvor, on the Croatian border. The Zagreb Corps reported that the entire national border in its AOR was secured and all its Operation Storm objectives had been achieved. Mopping up operations in Banovina lasted until 14 August, and special police units joined the operations on the Zrinska Gora and Petrova Gora mountains.[139]

Air force operations

[edit]

On 4 August 1995, the CAF had at its disposal 17 MiG-21s, five attack and nine transport helicopters, three transport airplanes and two reconnaissance aircraft. On that first day of the operation, thirteen MiG-21s were used to destroy or disable six targets in the Gospić and Zagreb Corps AORs, at the cost of one severely and three slightly damaged jets. The same day, three Mi-8s were used for medical evacuation.[140] US Navy EA-6Bs and F/A-18s on patrol as part of Operation Deny Flight fired on ARSK surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites at Udbina and Knin as SAM radars locked onto the jets.[141] A few sources claim that they were deployed as a deterrent as the UN troops came under HV fire,[142] and a subsequent UN Security Council report only notes that the deployment was a result of the deterioration of the military situation and resulting low security of the peacekeepers in the area.[143] Also on 4 August, the RSK 105th Aviation Brigade based at Udbina, deployed helicopters against the Croatian special police on Velebit Mountain and against targets in the Gospić area virtually to no effect.[140]

On 5 August, the RSK air force began evacuating to Zalužani Airfield near Banja Luka, completing the move that day. At the same time the CAF deployed 11 MiG-21s to strike a communications facility and a storage site, as well as five other military positions throughout the RSK. That day, the CAF also deployed a Mi-24 to attack ARSK armour units near Sisak and five Mi-8s to transport casualties, and move troops and cargo. Five CAF MiG-21s sustained light damage in the process. The next day, jets struck an ARSK command post, a bridge and at least four other targets near Karlovac and Glina. A Mi-24 was deployed to the Slunj area to attack ARSK tanks, while three Mi-8s transported wounded personnel and supplies. An additional pair of MiG-21s was deployed to patrol the airspace over Ivanić Grad and intercept two Bosnian Serb fighter jets, but they failed to do so due to fog in the area and their low level of flight.[140] The VRS aircraft subsequently managed to strike the Petrokemija chemical plant in Kutina.[144]

On 7 August, two VRS air force jets attacked a village in the Nova Gradiška area, just north of the Sava River—the international border in the area.[145] The CAF bombed an ARSK command post, a storage facility and several tanks near Bosanski Petrovac.[140] CAF jets also struck a column of Serb refugees near Bosanski Petrovac, killing nine people, including four children.[146] Croatia has denied that it targeted civilians.[147] On 8 August, the CAF performed its last combat sorties in the operation, striking tanks and armoured vehicles between Bosanski Novi and Prijedor, and two of its MiG-21s were damaged.[140] The same day, UN military observers deployed at Croatian airfields claimed that the CAF attacked military targets and civilians in the Dvor area,[144] where refugee columns were mixed with ARSK transporting heavy weapons and large quantities of ammunition.[148] Overall, the CAF performed 67 close air support, three attack helicopter, seven reconnaissance, four combat air patrol and 111 transport helicopter sorties during Operation Storm.[140]

Other coordinated operations

[edit]In order to protect areas of Croatia away from Sectors North and South, the HV conducted defensive operations while the HVO started a limited offensive north of Glamoč and Kupres to pin down part of the VRS forces, exploit the situation and gain positions for further advance.[149] On 5 August, the HVO 2nd and 3rd Guards Brigades attacked VRS positions north of Tomislavgrad, achieving small advances to secure more favourable positions for future attacks towards Šipovo and Jajce, while tying down part of the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps.[150] As a consequence of the overall battlefield situation, the VRS was limited to a few counter-attacks around Bihać and Grahovo as it was short of reserves.[151] The most significant counter-attack was launched by the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps on the night of 11/12 August. It broke through the 141st Brigade,[152] consisting of the HV's reserve infantry, reaching the outskirts of Bosansko Grahovo, only to be beaten back by the HV,[153] using one battalion drawn from the 4th Guards and the 7th Guards Brigade each, supported by the 6th and the 126th Home Guard Regiments.[152]

Operation Phoenix

[edit]In eastern Slavonia, the HV Osijek Corps was tasked with preventing ARSK or Yugoslav Army forces from advancing west in the region, and counter-attacking into the ARSK-held area around Vukovar. The Osijek Corps mission was codenamed Operation Phoenix (Croatian: Operacija Fenix). The Corps commanded the 3rd Guards and 5th Guards Brigades, as well as six other HV brigades and seven Home Guard regiments. Additional reinforcements were provided in a form of specialized corps-level units otherwise directly subordinated to the HV General Staff, including a part of the Mi-24 gunship squadron. Even though artillery rounds and small arms fire were traded between the HV and the ARSK 11th Slavonia-Baranja Corps in the region, no major attack occurred.[149] The most significant coordinated ARSK effort occurred on 5 August, when the exchange was compounded by three RSK air raids and an infantry and tank assault targeting Nuštar, northeast of Vinkovci.[154] Operation Storm led the Yugoslav Army to mobilize and deploy considerable artillery, tanks and infantry to the border area near eastern Slavonia, but it took no part in the battle.[151]

Operation Maestral

[edit]In the south of Croatia, the HV deployed to protect the Dubrovnik area against the VRS Herzegovina Corps and the Yugoslav Army situated in and around Trebinje and the Bay of Kotor. The plan, codenamed Operation Maestral, entailed deployment of the 114th, 115th and 163rd Brigades, the 116th and 156th Home Guard Regiments, the 1st Home Guard Battalion (Dubrovnik), the 16th Artillery Battalion, the 39th Engineers Battalion and a mobile coastal artillery battery. The area was reinforced on 8 August with the 144th Brigade as the unit completed its objectives in Operation Storm and moved to Dubrovnik. The CAF committed two MiG-21s and two Mi-24s based in Split to Operation Maestral. The Croatian Navy supported the operation deploying the Korčula, Brač and Hvar Marine Detachments, as well as missile boats, minesweepers, anti-submarine warfare ships and coastal artillery. In the period, the VRS attacked the Dubrovnik area intermittently using artillery only.[155]

Assessment of the battle

[edit]Operation Storm became the largest European land battle since the Second World War,[156] encompassing a 630-kilometre (390 mi) frontline.[65] It was a decisive victory for Croatia,[157][158][159][160] restoring its control over 10,400 square kilometres (4,000 square miles) of territory, representing 18.4% of the country.[161] Losses sustained by the HV and the special police are most often cited as 174 killed and 1,430 wounded,[162] but a government report prepared weeks after the battle specified 211 killed or missing, 1,100 wounded and three captured soldiers. By 21 August, Croatian authorities recovered and buried 560 ARSK servicemen killed in the battle. The HV captured 4,000 prisoners of war,[163] 54 armoured and 497 other vehicles, six aircraft, hundreds of artillery pieces and over 4,000 infantry weapons.[161] Four UN peacekeepers were killed—three as a result of HV actions and one as a result of ARSK activities—and 16 injured. The HV destroyed 98 UN observation posts.[164]

The HV's success was a result of a series of improvements to the HV itself and crucial breakthroughs made in the ARSK positions that were subsequently exploited by the HV and the ARBiH. The attack was not immediately successful everywhere, but the seizing of key positions led to the collapse of the ARSK command structure and overall defensive capability.[134] The HV's capture of Bosansko Grahovo just before Operation Storm and the special police's advance to Gračac made Knin nearly impossible to defend.[165] In Lika, two Guards brigades rapidly cut the ARSK-held area lacking tactical depth or mobile reserve forces, isolating pockets of resistance and placing the 1st Guards Brigade in a position that allowed it to move north into the Karlovac Corps AOR, pushing ARSK forces towards Banovina. The defeat of the ARSK at Glina and Petrinja, after heavy fighting, also defeated the ARSK Banija Corps, as its reserve became immobilized by the ARBiH. The ARSK force was capable of containing or substantially holding assaults by regular HV brigades and the Home Guard, but attacks by the Guards brigades and the special police proved to be decisive.[166] Colonel Andrew Leslie, commanding the UNCRO in the Knin area,[167] assessed Operation Storm as a textbook operation that would have "scored an A-plus" by NATO standards.[168]

Even if the ARBiH had not provided aid, the HV would almost certainly have defeated the Banija Corps on its own, albeit at greater cost. The lack of reserves was the ARSK's key weakness that was exploited by the HV and the ARBiH since the ARSK's static defence could not cope with fast-paced attacks. The ARSK military was unable to check outflanking manoeuvres and their Special Units Corps failed as a mobile reserve, holding back the HV's 1st Guards Brigade south of Slunj for less than a single day.[166] The ARSK traditionally counted on the VRS and the Yugoslav military as its strategic reserve, but the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina immobilized the VRS reserves and Yugoslavia did not intervene militarily as Milošević did not order it to do so. Even if he had wished to intervene, the speed of the battle would have allowed a very limited time for Yugoslavia to deploy appropriate reinforcements to support the ARSK.[151]

Refugee crisis

[edit]

The evacuation and following mass-exodus of the Serbs from the RSK led to a significant humanitarian crisis. In August 1995, the UN estimated that only 3,500 Serbs remained in Kordun and Banovina (former Sector North) and 2,000 remained in Lika and Northern Dalmatia (former Sector South), while more than 150,000 had fled to Yugoslavia, and between 10,000 and 15,000 had arrived in the Banja Luka area.[143] The number of Serb refugees was reported to be as many as 200,000 by the international media[169] and international organizations.[170] Also, 21,000 Bosniak refugees from the former APWB fled to Croatia.[143][171]

While approximately 35,000 Serb refugees, trapped with the surrendered ARSK Kordun Corps, were evacuated to Yugoslavia via Sisak and the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway,[126] the bulk of the refugees followed a route through the Republika Srpska, arriving there via Dvor in Banovina or via Srb in Lika—two corridors to Serb-held territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina left as the HV advanced.[102] The two points of retreat were created as a consequence of the delay of a northward advance of the HV Split Corps after the capture of Knin, and the decision not to use the entire HV 2nd Guards Brigade to spearhead the southward advance from Petrinja.[172] The retreating ARSK, transporting large quantities of weaponry, ammunition, artillery and tanks, often intermingled with evacuating or fleeing civilians, had few roads to use.[148] The escaping columns were reportedly intermittently attacked by CAF jets,[173] and the HV, trading fire with the ARSK located close to the civilian columns.[174] The refugees were also targeted by ARBiH troops,[175] as well as by VRS jets, and sometimes were run over by the ARSK Special Units Corps' retreating tanks.[176][177] On 9 August, a refugee convoy evacuating from the former Sector North under the terms of the ARSK Kordun Corps' surrender agreement was attacked by Croatian civilians in Sisak. The attack caused one civilian death, many injuries and damage to a large number of vehicles. Croatian police intervened in the incident after UN civilian police monitors pressured them to do so.[144] The next day, US ambassador to Croatia Peter Galbraith joined the column to protect them,[178] and the Croatian police presence along the planned route increased.[173] The refugees moving through the Republika Srpska were extorted at checkpoints and forced to pay extra for fuel and other services by local strongmen.[179]

Aiming to reduce evidence of political failure, Yugoslav authorities sought to disperse the refugees in various parts of Serbia and prevent their concentration in the capital, Belgrade.[180] The government encouraged the refugees to settle in predominantly Hungarian areas of Vojvodina, and in Kosovo, which was largely populated by Albanians, leading to increased instability in those regions.[181][182] Even though 20,000 were planned to be settled in Kosovo, only 4,000 moved to the region.[182] After 12 August, the Serbian authorities started to deport some of the refugees who were of military age, declaring them illegal immigrants.[183] They were turned over to the VRS or the ARSK in eastern Croatia for conscription.[184] Some of the conscripts were publicly humiliated and beaten for abandoning the RSK.[183] In some areas, ethnic Croats of Vojvodina were evicted from their homes by the refugees themselves to claim new accommodations.[185] Similarly, the refugees moving through Banja Luka forced Croats and Bosniaks out of their homes.[186]

Return of the refugees

[edit]At the beginning of the Croatian War of Independence, in 1991–1992, a non-Serb population of more than 220,000 was forcibly removed from Serb-held territories in Croatia, as the RSK was established.[187] In the wake of Operation Storm, a part of those refugees, as well as Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina, settled in a substantial number of housing units in the area formerly held by the ARSK, presenting an obstacle to the return of Serb refugees.[188] In September 2010, out of 300,000–350,000 Serbs who fled from Croatia during the entire war,[189] 132,707 were registered as having returned,[190] but only 60–65% of those were believed to reside permanently in the country. However, only 20,000–25,000 more were interested in returning to Croatia.[189] In 2010, approximately 60,000 Serb refugees from Croatia remained in Serbia.[191]

The ICTY stated that Croatia adopting discriminatory measures after the departures of Serb civilians from the Krajina does not demonstrate that these departures were forced.[192] Human Rights Watch reported in 1999 that Serbs did not enjoy their civil rights as Croatian citizens, as a result of discriminatory laws and practices, and that they were frequently unable to return to and live freely in Croatia.[193] The return of refugees has been hampered by several obstacles. These include property ownership and accommodation, as Croat refugees settled in vacated homes,[188] and Croatian war-time legislation that stripped the refugees once living in government-owned housing of their tenancy rights. The legislation was abolished following the war,[194] and alternative accommodation is offered to returnees.[195] 6,538 housing units were allocated by November 2010. Another obstacle is the difficulty for refugees to obtain residency status or Croatian citizenship. Applicable legislation has been relaxed since, and by November 2010, Croatia allowed the validation of identity documents issued by the RSK.[190] Even though Croatia declared a general amnesty, refugees fear legal prosecution,[194] as the amnesty does not pertain to war crimes.[196]

In 2015 and 2017 report, Amnesty International expressed concern about persisting obstacles for Serbs to regain their property.[197] They reported that Croatian Serbs continued to face discrimination in public sector employment and the restitution of tenancy rights to social housing vacated during the war. They also pointed to hate speech, "evoking fascist ideology" and the right to use minority languages and script continued to be politicized and unimplemented in some towns.[197]

War crimes

[edit]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), set up in 1993 based on the UN Security Council Resolution 827,[198] indicted Gotovina, Čermak and Markač for war crimes, specifically for their roles in Operation Storm, citing their participation in a joint criminal enterprise aimed at the permanent removal of Serbs from the ARSK-held part of Croatia. The ICTY charges specified that other participants in the joint criminal enterprise were Tuđman, Šušak, and Bobetko and Červenko,[199] however all except Bobetko were dead before the first relevant ICTY indictment was issued in 2001.[200] Bobetko was indicted by the ICTY, but died a year later, before he could be extradited for trial at the ICTY.[201] The trial of Gotovina et al began in 2008,[202] leading to the convictions of Gotovina and Markač and the acquittal of Čermak three years later.[203] Gotovina and Markač were acquitted on appeal in November 2012.[204] The ICTY concluded that Operation Storm was not aimed at ethnic persecution, as civilians had not been deliberately targeted. The Appeals Chamber stated that Croatian Army and Special Police committed crimes after the artillery assault, but the state and military leadership had no role in planning and creation of crimes. The ICTY concluded that Croatia did not have the specific intent of displacing the country's Serb minority.[205] Furthermore, they did not find that Gotovina and Markač played a role in adopting discriminatory efforts that prevent the return of Serb civilians.[192] Two judges in the panel of five dissented from this verdict.[206] The case raised significant issues for law of war and it has been described as a precedent.[207][208][209][210][211][212]

Views on whether Operation Storm itself as a whole was a war crime remain mixed. EU envoy Bildt, one of the few critics of the operation, accused Croatia of the most efficient ethnic cleansing carried out in the Yugoslav Wars. Croatia denied this claiming it had "urged Serbs to stay", however soldiers also engaged in shelling of Serb inhabited areas, killing of civilians and allowed Croats to engage in the burning and plundering of Serb homes, according to a UN report.[213] His view is supported by a number of Western analysts, such as Professor Marie-Janine Calic,[214] Miloševic biographer Adam LeBor,[215] and Professor Paul Mojzes,[216] while historians Gerard Toal and Carl T. Dahlman distinguish the Operation from "the practices of ethnic cleansing" that occurred during the offensive.[217] Historian Marko Attila Hoare disagrees that the operation was an act of ethnic cleansing, and points out that the Krajina Serb leadership evacuated the civilian population as a response to the Croatian offensive; whatever their intentions, the Croatians never had the chance to organise their removal.[218] The claims of ethnic cleansing were rejected by Galbraith.[219] Red Cross officials, UN observers and Western diplomats condemned Galbraith's denial of the ethnic cleansing, with one ambassador calling his remarks "breathtaking."[220] In the Gotovina Defence Final Trial Brief, Gotovina's lawyers Luka Misetic, Greg Kehoe and Payam Akhavan rejected the accusation of mass expulsion of Serbian population.[221] They referred to the ICTY testimony of RSK Commander Mile Mrkšić, who stated that on 4 August 1995, sometime after 16:00 hrs, it was Milan Martić and his staff who in fact made a decision to evacuate the Serb population from Krajina to Srb, a village near the Bosnian border.[222] Mojzes also notes that Serbs were ordered by their command to leave, at which a mass exodus took place from the entire Krajina region on "short notice".[223] ICTY findings also stated evidence indicating that General Gotovina "adopted numerous measures" to prevent and curb crimes and general disorder following the artillery attacks, including crimes against Serb civilians. [192]

In February 2015, at the conclusion of the Croatia–Serbia genocide case, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) dismissed a Serbian lawsuit which alleged that Operation Storm constituted genocide,[224] ruling that Croatia did not have the specific intent to exterminate the country's Serb minority, though it reaffirmed that serious crimes against Serb civilians had taken place.[224][225] The court also found that the HV left accessible escape routes for civilians.[226] They also found that, at most, the leaders of Croatia envisaged that the military offensive would have the effect of causing the flight of the great majority of the Serb population, that they were satisfied with that consequence and they wished to encourage the departure of the Serb civilians, but do not establish the existence of the specific intent which characterizes genocide.[227] According to the judgement, Serb civilians fleeing their homes, as well as those remaining in UN protected areas, were subject to various forms of harassment by both the HV and Croatian civilians.[228] On 8 August, a refugee column was shelled.[228]

The number of civilian casualties in Operation Storm is disputed. The State Attorney's Office of the Republic of Croatia claims that 214 civilians were killed—156 in 24 instances of war crimes and another 47 as victims of murder—during the battle and in its immediate aftermath. The Croatian Helsinki Committee disputes the claim and reports that 677 civilians were killed after Operation Storm, mainly old people who remained, while an additional 837 Serb civilians are listed as missing.[229][230] When submitted as evidence, their report was rejected by the ICTY due to unsourced statements and double entries contained within.[231] Other sources indicate 181 more victims were killed by Croatian forces and buried in a mass grave in Mrkonjić Grad, following a continuation of the Operation Storm offensive into Bosnia.[232][233] Serbian sources quote 1,192 civilians dead or missing.[234] ICTY prosecutors set the number of civilian deaths at 324.[235] Croatian government officials estimate that 42 Croatian civilians were killed during the operation.[236]