Ubaid period: Difference between revisions

additional section on Mesopotamian climate and environment during the Ubaid period |

→Ubaid 4: update dating & distribution section; some of the images that were there will appear in another section that will be moved into the article after this one. Please note that virtually no information from the previous version will be lost - although the article itself will be re-arranged considerably Tags: Visual edit Disambiguation links added |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

The available evidence in northern Mesopotamia points to a cooler and drier climate during the Hassuna and Halaf periods. During the [[Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period|Halaf-Ubaid Transitional]] (HUT), Ubaid and early Uruk periods, this developed into a climate characterised by stronger [[Seasonality|seasonal variation]], heavy [[Rain|torrential rains]] and dry summers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hole |first=Frank |date=1997 |title=Paleoenvironment and Human Society in the Jezireh of Northern Mesopotamia 20 000-6 000 BP. |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1997_num_23_2_4651 |journal=Paléorient |language=fr-FR |volume=23 |issue=2 |pages=39–49 |doi=10.3406/paleo.1997.4651 |issn=0153-9345}}</ref> |

The available evidence in northern Mesopotamia points to a cooler and drier climate during the Hassuna and Halaf periods. During the [[Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period|Halaf-Ubaid Transitional]] (HUT), Ubaid and early Uruk periods, this developed into a climate characterised by stronger [[Seasonality|seasonal variation]], heavy [[Rain|torrential rains]] and dry summers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hole |first=Frank |date=1997 |title=Paleoenvironment and Human Society in the Jezireh of Northern Mesopotamia 20 000-6 000 BP. |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1997_num_23_2_4651 |journal=Paléorient |language=fr-FR |volume=23 |issue=2 |pages=39–49 |doi=10.3406/paleo.1997.4651 |issn=0153-9345}}</ref> |

||

==Dating |

== Dating and geographical distribution == |

||

Ubaid and Ubaid-like material culture has been found over an immense area. Ubaid ceramics have shown up from [[Yumuktepe|Mersin]] in the west to {{ill|Tepe Ghabristan|wd=Q109293319|s=1|v=sup}} in the east, and from [[Norşuntepe]] and [[Melid|Arslantepe]] in the north to [[Dosariyah]] in the south along the [[Persian Gulf|Gulf]] coast of [[Saudi Arabia]].<ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Baldi |first=Johnny Samuele |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1200195553 |title=Proceedings of the 5th "Broadening Horizons" Conference (Udine 5-8 June, 2017). |date=2020 |isbn=978-88-5511-046-4 |editor-last=Iamoni |editor-first=Marco |location=Trieste |pages=71–87 |chapter=Evolution as a way of intertwining: regional approach and new data on the Halaf-Ubaid transition in Northern Mesopotamia |oclc=1200195553}}</ref> In this area, researchers have discerned considerable regional variation, indicating that the Ubaid was not a monolithic culture through time and space.<ref name=":02">{{Cite book |last1=Carter |first1=Robert A. |url=https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf |title=Beyond the Ubaid : transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East |last2=Philip |first2=Graham |date=2010 |publisher=Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago |others=Robert A. Carter, Graham Philip, University of Chicago. Oriental Institute, Grey College |isbn=978-1-885923-66-0 |location=Chicago, Ill. |pages=1–22 |chapter=Deconstructing the Ubaid |oclc=646401242}}</ref> |

|||

The Ubaid period is divided into six ''[[Phase (archaeology)|phases]]'', ''styles'', and/or ''periods'': |

|||

*Ubaid 0 (alternatively: the Oueili style; {{circa|6500|5400 BC}}) is an Early Ubaid style first excavated at [[Tell el-'Oueili]].{{sfn|Kuhrt|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V_sfMzRPTgoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q&f=true 22]}}{{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}} |

|||

*Ubaid 1 (alternatively: the Ubaid I, Early Ubaid, or Eridu style; {{circa|5400|4700 BC}}) is a style centered at [[Tell Abu Shahrain]] and limited to southern Iraq—on what was then the shores of the [[Persian Gulf]]. This style—showing clear connection to the [[Samarra culture]] to the north—saw the establishment of the first permanent settlement south of the [[Isohyet#Precipitation and air moisture|five-inch rainfall isohyet]]. These people pioneered the growing of grains in the extreme conditions of aridity; thanks to the high [[water table]]s of southern Iraq.{{sfn|Roux|1966}}{{sfn|Kuhrt|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V_sfMzRPTgoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q&f=true 22]}}{{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}} |

|||

*Ubaid 2 (alternatively: the Ubaid II or Hadji Muhammed style; {{circa|4800|4500 BC}}) is the style centered at [[Hadji Muhammed]] that saw the development of extensive [[canal]] networks from major settlements. Irrigation agriculture (which seems to have developed first at [[Choga Mami]] and rapidly spread elsewhere) was pioneered by farmers who may have also brought with them elements of the Samarran culture from the first required collective effort and centralized coordination of labor.{{sfn|Wittfogel|2010}}{{sfn|Kuhrt|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V_sfMzRPTgoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q&f=true 22]}}{{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}} |

|||

*Ubaid 3 (alternatively: the Ubaid III style; {{circa|5300|4700 BC}}) ceramics have been discovered at the [[type site]] for which the period is named after: Tell al-'Ubaid. The appearance of these ceramics received different dates depending on the particular [[archaeological sites]], which have a wide geographical distribution. In recent studies; there's a tendency to narrow this period somewhat.{{sfn|Kuhrt|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V_sfMzRPTgoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q&f=true 22]}}{{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}} |

|||

*Ubaid 4 (alternatively: the Ubaid IV or Late Ubaid style; {{circa|4700|4200 BC}}){{sfn|Kuhrt|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V_sfMzRPTgoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q&f=true 22]}}{{sfn|Carter|2006b}}{{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}}{{sfn|Ashkanani|Tykot|Al-Juboury|Stremtan|2019}} |

|||

*Ubaid 5 (alternatively: the Ubaid V or Terminal Ubaid style; {{circa|4200|3800 BC}}){{sfn|Carter|2006a|pp=[https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf 1–22]}} |

|||

The Ubaid period is most commonly divided in 6 phases, called Ubaid 0-5. Some of these phases equate with pottery styles that were, in earlier publications, considered to be distinct from Ubaid, but that are now considered to be part of the same phenomenon. Some of these styles, such as Hajji Muhammed (previously thought to be Ubaid 2) are now known to occur in Ubaid 3 contexts as well, thereby limiting their value as chronological markers. The [[Relative dating|relative chronology]] is based on the long stratigraphic sequences of sites such as Ur, Eridu and Tepe Gawra. The [[Absolute dating|absolute chronology]] is harder to establish, mainly due to a lack of abundant radiocarbon dates coming from southern Mesopotamia. |

|||

===Ubaid 0-1=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

|+Relative Ubaid chronology |

|||

Ubaid 0-1 pottery - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06926.JPG|Ubaid 0-1; pottery; [[Godin Tepe]]; [[Oriental Institute Museum]], [[Chicago]], [[USA]] |

|||

!phase |

|||

Ubaid 0-1 pottery footed bowl - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06927.JPG|Ubaid 0-1; footed bowl; Godin Tepe; Oriental Institute Museum |

|||

!alternative name |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

!Northern Mesopotamia |

|||

!date (BC) |

|||

<small>(after Pournelle 2003 / after Harris 2021)</small><ref>{{Cite book |last=Pournelle |first=Jennifer R. |url=https://www.proquest.com/openview/216b5aa11d77b2e3bbe71310be970cf7/1 |title=Marshland of cities: Deltaic landscapes and the evolution of early Mesopotamian civilization |year=2003}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Harris |first=Samuel Lee |date=2021 |title=Public Works and Private Work on the Threshold of Complexity: The Production and Use of Space at Late Chalcolithic 1 Tell Surezha, Iraq - ProQuest |url=https://www.proquest.com/openview/ed64ba8e70c8151531ea8c2fb8edbf0d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y |access-date=2022-01-26 |website=www.proquest.com |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 0 |

|||

|Oueili phase |

|||

|Early Pottery Neolithic |

|||

|6500-5900 / 6800-6200 |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 1 |

|||

|Eridu style |

|||

|[[Halaf culture|Halaf]] |

|||

|5900-5200 / 6200-5500 |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 2 |

|||

|Hajji Muhammad style |

|||

|[[Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period|Halaf-Ubaid Transitional]] |

|||

|5200-5100 / 5500-5200 |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 3 |

|||

|Tell al-'Ubaid style |

|||

|Northern Ubaid |

|||

|5100-4900 / 5200-4600 |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 4 |

|||

|Late Ubaid |

|||

|Northern Ubaid |

|||

|4900-4350 / 5200-4600 |

|||

|- |

|||

|Ubaid 5 |

|||

|Terminal Ubaid |

|||

|Late Chalcolithic 1 |

|||

|4350-4200 / 4600-4200 |

|||

|} |

|||

=== |

=== Southern Mesopotamia === |

||

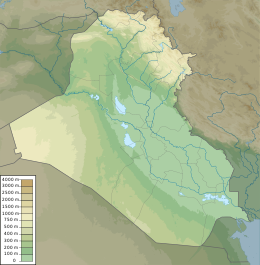

{{Location map+|Iraq|width=260|float=right|relief=yes|caption=Map of important Ubaid period sites in Iraq.|places={{Location map~|Iraq|lat=30.97|long=46.025556|position=right|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell al-'Ubaid|'Ubaid]]}} |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=30.815833|long=45.996111|position=left |label_size=75 |label=[[Eridu]]}} |

|||

Ubaid 2 pottery - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06928.JPG|Ubaid 2; pottery; Oriental Institute Museum |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=30.9625|long=46.103056|position=bottom |label_size=75 |label=[[Ur]]}} |

|||

Northern Ubaid pottery from Tepe Gawra and other sites - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06940.JPG|Northern Ubaid; pottery; Tepe Gawra; Oriental Institute Museum |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=31.243|long=45.885|position=top|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell el-'Oueili|'Oueili]]}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=34.1|long=45.12|position=right |label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Abada]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=34.38|long=44.99|position=right |label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Madhur]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=36.495556|long=43.260278|position=right|label_size=75 |label=[[Tepe Gawra]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=36.371389|long=43.197778|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Arpachiyah|Arpachiyah]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=31.324167|long=45.637222|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Uruk]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=32.781667|long=44.664722|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Uqair]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=29.641667|long=48.150556|position=top|label_size=75 |label=[[H3]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Iraq|lat=29.659722|long=48.051111|position=bottom|label_size=75 |label=[[Bahra 1]]}}}} |

|||

In the south, corresponding to the area that would later be known as [[Sumer]], the entire Ubaid spans an immense period from ca. 6500 to 3800 BC.<ref name=":02" /> It is here that the oldest known Ubaid site - [[Tell el-'Oueili]] - was found. In southern [[Iraq]], no archaeological site has yet yielded remains older than Ubaid, However, this might be more a result of the fact that such ancient settlements are now buried deep under alluvial sediments. This was the case, for example, of the site of [[Hadji Muhammed]], which was discovered only by accident.<ref name=":52">{{Cite book |last=McMahon |first=A. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/reallexikon-der-assyriologie-und-vorderasiatischen-archaologie-14-band-tiergefa-wasaezzili/oclc/985433875 |title=Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Band, 14. Band |date=2014 |isbn=978-3-11-041761-6 |pages=261–265 |language=English |chapter='Ubaid-Kultur, -Keramik |oclc=985433875}}</ref> |

|||

=== Central and northern Mesopotamia === |

|||

===Ubaid 3=== |

|||

{{Location map+|Ottoman Empire1914|width=260|float=right|relief=yes|caption=Map of important Ubaid period sites in northern Mesopotamia.|places={{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=36.8|long=34.4|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Mersin]]}} |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

{{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=38.618889|long=39.47|position=right|label_size=75 |label=[[Norşuntepe]]}} |

|||

Ubaid III pottery jar 5300-4700 BC Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid III; jar; {{circa|5300|4700 BC}}; [[Louvre Museum]] AO 29611{{sfn|Raux|1989d}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=35.95|long=39.066667|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Zeidan]]}} |

|||

Ubaid III pottery 5300-4700 BC Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid III; pottery; {{circa|5300|4700 BC}}; Louvre Museum AO 29598{{sfn|Raux|1989a}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=38.381944|long=38.361111|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Arslantepe]]}} |

|||

Ubaid III campaniform pottery 5300-4700 BC Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid III; campaniform pottery; {{circa|5300|4700 BC}}; Louvre Museum AO 29598 |

|||

{{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=36.667617|long=41.058644|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Tell Brak]]}} |

|||

Ubaid III pottery 5300 - 4700 BC. Louvre Museum AO 29616.jpg|Ubaid III; pottery; {{circa|5300|4700 BC}}; Louvre Museum AO 29616{{sfn|Raux|1989c}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Ottoman Empire1914|lat=36.495556|long=43.260278|position=right|label_size=75 |label=[[Tepe Gawra]]}}}} |

|||

Ubaid 3-4 pottery - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06929.JPG|Ubaid 3-4; pottery; Oriental Institute Museum |

|||

In central and northern Iraq, the Ubaid was preceded by the [[Hassuna culture|Hassuna]] and [[Samarra culture|Samarra]] cultures. The Ubaid may have developed out of the latter.<ref name=":9">{{Cite book |last=Peasnall |first=Brian |title=Encyclopedia of Prehistory |date=2002 |work= |publisher=Springer US |isbn=978-1-4684-7135-9 |editor-last=Peregrine |editor-first=Peter N. |place=Boston, MA |pages=372–390 |language=en |chapter=Ubaid |doi=10.1007/978-1-4615-0023-0_37 |access-date=2021-10-04 |editor2-last=Ember |editor2-first=Melvin |chapter-url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4615-0023-0_37}}</ref> In northern Syria and southeastern Turkey, the Ubaid follows upon the [[Halaf culture|Halaf period]], and a relatively short [[Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period]] (HUT) dating to c. 5500-5200 BC has been proposed as well.<ref name=":6" /> HUT pottery assemblages displayed both typically Ubaid and Halaf characteristics.<ref name=":7">{{Cite book |last=Özbal |first=Rana |url=http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195376142-e-8 |title=The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE) |date=2012-11-21 |publisher=Oxford University Press |editor-last=McMahon |editor-first=Gregory |volume=1 |language=en |chapter=The Chalcolithic of Southeast Anatolia |doi=10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0008 |editor-last2=Steadman |editor-first2=Sharon}}</ref> The relations between these periods - or cultures - is complex and not yet fully understood, including how and when exactly the Ubaid started to appear in northern Mesopotamia. To resolve these issues, modern scholarship tends to focus more on regional trajectories of change where different cultural elements from the Halaf, Samarra, or Ubaid - pottery, architecture, and so forth - could co-exist. This makes it increasingly hard to define an occupation phase at a site as, for example, purely Ubaid or purely Halaf.<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Campell |first=Stuart |date=2007 |title=Rethinking Halaf Chronologies |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_2007_num_33_1_5209 |journal=Paléorient |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=103–136 |doi=10.3406/paleo.2007.5209}}</ref> |

|||

Ubaid 3-4 pottery ax, sickle, and bent nail - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06929.JPG|Ubaid 3-4; a sickle and bent nail; clay; Oriental Institute Museum |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

In northern Mesopotamia, Ubaid characteristics only start to appear in Ubaid 2-3, i.e. toward the end of the sixth millennium BC, so that the entire Ubaid period would be much shorter. For [[Syria]], a range of 5300-4300 BC has been suggested.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last1=Akkermans |first1=Peter M. M. G. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50322834 |title=The archaeology of Syria : from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC) |last2=Schwartz |first2=Glenn M. |date=2003 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-521-79230-4 |location=Cambridge, UK |oclc=50322834}}</ref> However, some scholars have argued that the interaction between the originally southern Mesopotamian Ubaid and the north started already during Ubaid 1-2.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

===Ubaid 4=== |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

Ubaid IV pottery gobelet 4700-4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu. Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid IV; pottery gobelet; {{circa|5900|3700 BC}}; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 15334{{sfn|Raux|1932d}} |

|||

Ubaid IV pottery jars 4700-4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid IV; pottery jars; {{circa|4700|4200 BC}}; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 14281{{sfn|Raux|1931}} |

|||

Female figurines Ubaid IV Tello ancient Girsu 4700-4200 BC Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid IV; two female figurines; {{circa|4700|4200 BC}}; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 15327{{sfn|Raux|1932a}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== |

=== Persian Gulf === |

||

{{Location map+|Persian Gulf|width=260|float=right|relief=yes|caption=Map of important Ubaid period sites along the [[Persian Gulf]] coast.|places={{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=29.641667|long=48.150556|position=top|label_size=75 |label=[[H3]]}} |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

{{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=24.516667|long=52.316667|position=right |label_size=75 |label=[[Dalma (island)]]}} |

|||

Ubaid IV pottery 4700-4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum.jpg|Ubaid 5; pottery; {{circa|3900|3500 BC}}; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 15338{{sfn|Raux|1932b}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=29.659722|long=48.051111|position=bottom|label_size=75 |label=[[Bahra 1]]}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

{{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=26.877|long=49.818|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Dosariyah]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=25.94|long=51.02|position=right|label_size=75 |label=[[Wadi Debayan]]}} |

|||

{{Location map~|Persian Gulf|lat=25.592|long=49.60|position=left|label_size=75 |label=[[Ain Qannas]]}}}} |

|||

Ubaid pottery started to appear along the Persian Gulf coast toward the end of the sixth millennium BC, reaching a peak around 5300 BC and continuing into the fifth millennium. Coastal sites where Ubaid pottery has been found include [[Bahra 1]] and H3 in Kuwait, Dosariyah in Saudi Arabia, and also island sites such as [[Dalma (island)|Dalma Island]] in the [[United Arab Emirates]]. Ubaid pottery has also been found further inland along the central Gulf coast at sites like [[Ain Qannas]], suggesting that the pottery may have been traded and valued in and of itself, rather than just being a container for some other commodity. This suggestion is reinforced by locally-produced pottery imiting Ubaid wares found at Dosariyah. It is unclear which products were exchanged for the pottery. Suggestions include foodstuffs (dates), semi-precious materials, jewellery (made from [[pearl]] and [[Seashell|shell]]), animal products, and livestock. Notably, the degree of cultural interaction between the Ubaid and local Neolithic communities is much stronger in the area of Kuwait than further south, up to the point that it has been suggested that Mesopotamians may have actually lived (part of the year) at sites like H3 and Bahra 1.<ref name=":10">{{Cite book |last=Carter |first=Robert |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/globalization-in-prehistory/globalising-interactions-in-the-arabian-neolithic-and-the-ubaid/F23D3846D6E8F81ED132A55586428C02 |title=Globalization in Prehistory: Contact, Exchange, and the 'People Without History' |date=2018 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-42980-1 |editor-last=Frachetti |editor-first=Michael D. |place=Cambridge |pages=43–79 |chapter=Globalising Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic and the 'Ubaid |access-date=2021-08-26 |editor2-last=Boivin |editor2-first=Nicole}}</ref> Small objects such as labrets, tokens, clay nails and small tools that may have had cosmetic use, and that are known from southern Mesopotamian sites also occur on sites along the Gulf coast, notably the sites in Kuwait.<ref name=":11">{{Cite journal |last=Carter |first=Robert |date=2020 |title=The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aae.12145 |journal=Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy |language=en |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=69–85 |doi=10.1111/aae.12145 |issn=0905-7196 |s2cid=213877028}}</ref> |

|||

Conversely, there is also evidence for Arabian Neolithic material in southern Mesopotamia. It has been noted that certain types of flint arrowheads found at Ur show clear resemblance with the Arabian Bifacial Tradition. Arabian Coarse Ware has been found at the sites of 'Oueili and Eridu. As at the sites in Kuwait, it may have been possible that Arabian Neolithic persons lived in southern Mesopotamia.<ref name=":11" /> |

|||

==Influence to the north== |

|||

{{More citations needed|section|date=May 2022}} |

|||

[[File:Mesopotamian Prehistorical cultures.jpg|thumb|left|A map of the Near East depicting the approximate extent of the: |

|||

{{legend|#B57EDC|[[Samarra culture]]}} |

|||

{{legend|#FFFACD|[[Hassuna culture]]}} |

|||

{{legend|#008000|[[Halaf culture]]}} |

|||

{{legend|#FF8000|Eridu culture}}{{Legend|#b73828|Pre-Pottery Neolithic Site}}]] |

|||

Around 5000 BC, the Ubaid culture spread into northern Mesopotamia and was adopted by the [[Halaf culture]].{{sfn|Pollock|Bernbeck|2009|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=bRUMQb_1uKcC&lpg=PA190&pg=PA190#v=onepage&q&f=true 190]}}{{sfn|Akkermans|2003|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=_4oqvpAHDEoC&lpg=PA157&pg=PA157#v=onepage&q&f=true 157]}} This is known as the [[Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period]] of northern Mesopotamia. |

|||

During the late Ubaid period around 4500–4000 BC, there was some increase in social polarization, with central houses in the settlements becoming bigger. But there were no real cities until the later [[Uruk period]]. |

|||

==Ubaid influence in the Persian Gulf area== |

|||

{{Continental Asia in 5000 BCE|right|The Ubaid culture and contemporary cultures circa 5000 BC|{{Annotation|50|85|[[File:Red circle 50%.svg|25px]]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=7|color=#000000}}}} |

|||

During the Ubaid 2 and 3 periods (5500–5000 BC), southern Mesopotamian Ubaid influence is felt further to the south along the coast of the [[Persian Gulf]]. [[Kuwait]] was the central site of interaction between the peoples of Mesopotamia and Neolithic [[Eastern Arabia]],<ref name="meso">{{cite journal|first=Robert|last=Carter|year=2019|title=The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC|url=https://www.academia.edu/41130012|journal=Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy|volume=31|issue=1|pages=69–85|doi=10.1111/aae.12145|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Robert|last=Carter|title=Maritime Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic: The Evidence from H3, As-Sabiyah, an Ubaid-Related Site in Kuwait|url=http://www.brill.com/maritime-interactions-arabian-neolithic|isbn=9789004163591|publisher=BRILL|date=25 October 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|first=Robert|last=Carter|title=Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC|journal=Antiquity |date=2006 |volume=80 |issue=307 |pages=52–63 |doi=10.1017/s0003598x0009325x |url=http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3673/1/3673.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|first=Robert|last=Carter|title=Maritime Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic: The Evidence from H3, As-Sabiyah, an Ubaid-Related Site in Kuwait|url=http://www.bookdepository.com/Maritime-Interactions-Arabian-Neolithic/9789004163591}}</ref><ref name=subiya>{{cite web|title=How Kuwaitis lived more than 8,000 years ago|url=https://www.pressreader.com/kuwait/kuwait-times/20141126/281775627470174|work=[[Kuwait Times]]|date=2014-11-25}}</ref> including [[Bahra 1]] and [[H3 (Kuwait)|site H3]] in [[Subiya, Kuwait|Subiya]].<ref name="meso"/><ref>{{cite journal|first=Robert|last=Carter|title=Ubaid-period boat remains from As-Sabiyah: excavations by the British Archaeological Expedition to Kuwait|journal=Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies|volume=32|pages=13–30|jstor=41223721|year=2002}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|first1=Robert |last1=Carter |first2=Graham |last2=Philip |title=Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East|url=https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc63.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://pcma.uw.edu.pl/en/2018/05/15/pam-22-2/|title=PAM 22|website=pcma.uw.edu.pl}}</ref> Ubaid artifacts spread also all along the Arabian [[Littoral zone|littoral]], showing the growth of a trading system that stretched from the Mediterranean coast through to [[Oman]].{{sfn|Bibby|2008}}{{sfn|Crawford|1998}} |

|||

Spreading from [[Eridu]], the Ubaid culture extended from the Middle of the [[Tigris]] and [[Euphrates]] to the shores of the [[Persian Gulf]], and then spread down past [[Bahrain]] to the copper deposits at Oman. |

|||

===Obsidian trade=== |

|||

[[File:Map Ubaid culture-en.svg|thumb|left|A map of the Near East showing various prehistoric and ancient sites that may have been inhabited {{circa|5900|4300 BC}}.]] |

|||

Starting around 5500 BC, Ubaid pottery of periods 2 and 3 has been documented at [[H3 (Kuwait)|site H3]] in Kuwait and in [[Dosariyah]] in eastern Saudi Arabia. |

|||

In Dosariyah, nine samples of Ubaid-associated [[obsidian]] were analyzed. They came from eastern and northeastern [[Anatolia]], such as from [[Pasinler, Erzurum]], as well as from [[Armenia]]. The obsidian was in the form of finished blade fragments.{{sfn|Khalidi|Gratuze|2016}} |

|||

===Decline of influence=== |

|||

The archaeological record shows that Arabian Bifacial/Ubaid period came to an abrupt end in eastern Arabia and the Oman peninsula at 3800 BC, just after the phase of lake lowering and onset of dune reactivation.{{sfn|Parker|Goudie|Stokes|White|2017}} At this time, increased aridity led to an end in semi-desert nomadism, and there is no evidence of human presence in the area for approximately 1,000 years, the so-called "Dark Millennium".{{sfn|Uerpmann|2003|pp=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Archaeology_of_the_United_Arab_Emirates/8Q6QnxfoRQ8C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA74&printsec=frontcover 74–81]}} The increased aridity might have been due to the [[5.9 kiloyear event]] at the end of the [[Older Peron]].{{sfn|Parker|Goudie|Stokes|White|2017}} |

|||

Numerous examples of Ubaid pottery have been found along the Persian Gulf, as far as [[Dilmun]], where [[Indus Valley civilization]] pottery has also been found.{{sfn|Stiebing Jr.|2016|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=DoyTDAAAQBAJ&lpg=PA85&pg=PA85#v=onepage&q&f=true 85]}} |

|||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

| Line 130: | Line 140: | ||

During the Ubaid Period (5000–4000 BC), the movement towards urbanization began. "Agriculture and animal husbandry [domestication] were widely practiced in sedentary communities".{{sfn|Pollock|1999}} There were also tribes that practiced domesticating animals as far north as Turkey, and as far south as the [[Zagros Mountains]].{{sfn|Pollock|1999}} The Ubaid period in the south was associated with intensive irrigated [[hydraulic agriculture]], and the use of the plough, both introduced from the north, possibly through the earlier [[Choga Mami]], [[Hadji Muhammed]] and [[Samarra culture]]s. |

During the Ubaid Period (5000–4000 BC), the movement towards urbanization began. "Agriculture and animal husbandry [domestication] were widely practiced in sedentary communities".{{sfn|Pollock|1999}} There were also tribes that practiced domesticating animals as far north as Turkey, and as far south as the [[Zagros Mountains]].{{sfn|Pollock|1999}} The Ubaid period in the south was associated with intensive irrigated [[hydraulic agriculture]], and the use of the plough, both introduced from the north, possibly through the earlier [[Choga Mami]], [[Hadji Muhammed]] and [[Samarra culture]]s. |

||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

The archaeological record shows that Arabian Bifacial/Ubaid period came to an abrupt end in eastern Arabia and the Oman peninsula at 3800 BC, just after the phase of lake lowering and onset of dune reactivation.{{sfn|Parker|Goudie|Stokes|White|2017}} At this time, increased aridity led to an end in semi-desert nomadism, and there is no evidence of human presence in the area for approximately 1,000 years, the so-called "Dark Millennium".{{sfn|Uerpmann|2003|pp=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Archaeology_of_the_United_Arab_Emirates/8Q6QnxfoRQ8C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA74&printsec=frontcover 74–81]}} The increased aridity might have been due to the [[5.9 kiloyear event]] at the end of the [[Older Peron]].{{sfn|Parker|Goudie|Stokes|White|2017}} |

|||

Bowl MET DP104229.jpg|Bowl; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; [[ceramic]]; 6.99 cm; Tell Abu Shahrain; [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] |

|||

Bowl MET DP104227.jpg|Bowl; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; Tell Abu Shahrain; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Bowl MET DP104228 (cropped).jpg|Bowl; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 5.08 cm; Tell Abu Shahrain; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Early Ubaid pottery 5100-4500 BC Tepe Gawra Louvre Museum DAO 3.jpg|Pottery; {{circa|5100|4500 BC}}; ceramic; Tepe Gawra; [[Louvre Museum]] |

|||

Cup MET ME49 133 5.jpg|Cup; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 8.56 cm; Tell Abu Shahrain; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Cup MET ME49 133 6.jpg|Cup; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 9.53 cm; Tell Abu Shahrain; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Jar MET ME49 133 13.jpg|Jar; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 15.24 cm; Tell Abu Shahrain; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Pottery bowl from Telul eth-Thalathat, Iraq. Ubaid period, c. 5000 BCE. Iraq Museum.jpg|Pottery bowl with a rounded bottom and monochrome paint (rosettes); {{circa|5000 BC}}; Telul eth-Thalathat; [[Iraq Museum]] |

|||

Shallow dish - Ubaid.jpg|Late Ubaid; shallow dish decorated with geometric designs in dark paint; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}}; Tell al-'Ubaid; [[British Museum]] |

|||

Spouted jar - Ur Ubaid period.jpg|Late Ubaid; spouted jar decorated with geometric designs in dark paint; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}}; Tell el-Muqayyar; British Museum |

|||

Bowl - Ur Ubaid period.jpg|Late Ubaid; painted bowl, decorated with geometric designs in dark paint; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}}; Tell el-Muqayyar; British Museum |

|||

Cup - Mefesh Ubaid period.jpg|Late Ubaid; painted cup, decorated with geometric designs in dark paint tattoos; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}} |

|||

Lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child, from Ur, Iraq, c. 4000 BCE. Iraq Museum (retouched).jpg|Late Ubaid; figurine of a lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child; terracotta and bitumen; {{circa|4000 BC}}; [[Iraq Museum]] |

|||

Ubaid 4; two lizard-headed female figurines with bitumen headdresses; {{circa|4500|4000 BC}}; Tell el-Muqayyar; Louvre Museum |

|||

Female clay figurine - Ubaid period - Ur - ME 122873.jpg|Figurine of a woman feeding a child and decorated to show jewellery or tattoos; clay; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}}; Tell el-Muqayyar |

|||

Female clay figurine - Ubaid period - Ur - ME 122872.jpg|Female figurine; clay; {{circa|5200|4200 BC}}; Tell el-Muqayyar |

|||

Funde.jpg|Painted pottery; ceramic; [[silex]] and/or [[obsidian]] stone tool; Dosariyah |

|||

Iran époque d'Obeid Sèvres.jpg|Goblet and cup; {{circa|4000 BC}}; Susa; [[Sèvres – Cité de la céramique]] museum |

|||

Frieze-group-3-example1.jpg|Late Ubaid; pottery jar; Southern Iraq; [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Society== |

==Society== |

||

| Line 164: | Line 155: | ||

There is some evidence of warfare during the Ubaid period although it is extremely rare. The [[Tell Sabi Abyad#Burnt_Village|"Burnt Village"]] at Tell Sabi Abyad could be suggestive of destruction during war but it could also have been due to other causes, such as wildfire or accident. Ritual burning is also possible since the bodies inside were already dead by the time they were burned. A mass grave at [[Tepe Gawra]] contained 24 bodies apparently buried without any funeral rituals, possibly indicating it was a mass grave from violence. Copper weapons were also present in the form of arrow heads and sling bullets, although these could have been used for other purpose; two clay pots recovered from the era have decorations showing arrows used for the purpose of hunting. A copper axe head was made in the late Ubaid period, which could have been a tool or a weapon.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hamblin|first=William J.|title=Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy warriors at the dawn of history|publisher=Routledge|year=2006|page=28-29}}</ref> |

There is some evidence of warfare during the Ubaid period although it is extremely rare. The [[Tell Sabi Abyad#Burnt_Village|"Burnt Village"]] at Tell Sabi Abyad could be suggestive of destruction during war but it could also have been due to other causes, such as wildfire or accident. Ritual burning is also possible since the bodies inside were already dead by the time they were burned. A mass grave at [[Tepe Gawra]] contained 24 bodies apparently buried without any funeral rituals, possibly indicating it was a mass grave from violence. Copper weapons were also present in the form of arrow heads and sling bullets, although these could have been used for other purpose; two clay pots recovered from the era have decorations showing arrows used for the purpose of hunting. A copper axe head was made in the late Ubaid period, which could have been a tool or a weapon.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hamblin|first=William J.|title=Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy warriors at the dawn of history|publisher=Routledge|year=2006|page=28-29}}</ref> |

||

<gallery widths="200px"heights="200px"perrow="4"> |

|||

During the late Ubaid period around 4500–4000 BC, there was some increase in social polarization, with central houses in the settlements becoming bigger. But there were no real cities until the later [[Uruk period]]. |

|||

Stamp seal and modern impression. Horned animal and bird,6th–5th millennium B.C. Northern Syria or Southeastern Anatolia. Ubaid Period. Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg|Stamp seal and modern impression: horned animal and bird; 6th–5th millennium |

|||

Drop-shaped (tanged) pendant seal and modern impression. Quadrupeds, ca. 4500–3500 B.C. Late Ubaid - Middle Gawra. Northern Mesopotamia.jpg|Late Ubaid–Middle Gawra; drop-shaped (tanged) pendant seal and modern impression with quadrupeds, not entirely reduced to geometric shapes; {{circa|4500|3500 BC}}; Northern Mesopotamia; Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

Stamp seal with Master of Animals motif, Tello, ancient Girsu, End of Ubaid period, Louvre Museum AO14165 (detail).jpg|Stamp seal with [[Master of Animals]] motif; {{circa|4000 BC}}; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 15388{{sfn|Raux|1932c}}{{sfn|Charvát|2002|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=NZOS7lUY8NUC&pg=PT96 96]}}{{sfn|Brown|Feldman|2013|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=F4DoBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA304 304]}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 09:10, 3 July 2024

A clickable map of Iraq detailing important sites that were occupied during the Ubaid period. | |

| Geographical range | Near East |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 5500 – c. 3700 BC |

| Type site | Tell al-'Ubaid |

| Major sites | |

| Preceded by | |

| Followed by | |

| History of Iraq |

|---|

|

|

|

| The Neolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Mesolithic |

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

The Ubaid period (c. 5500–3700 BC)[1] is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.[2]

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium.[3] In the south it has a very long duration between about 5500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.[1]

In Northern Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC.[1] It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

History of research

The excavators of Eridu and Tell al-'Ubaid found Ubaid pottery for the first time in the 1910-20s.[4] In 1930, the attendees at a conference in Baghdad defined the concept of an "Ubaid pottery style". This characteristic pottery of this style was a black-on-buff painted ware. This conference also defined the Eridu and Hajji Muhammed styles.[5] Scholars at this conference thought that these pottery styles were so different that "[...] they could not have developed out of the old, as is the case with the Uruk ware after the al-'Ubaid ware [...]". For many attendants of the conference, "this sequence based largely on pottery represented a series of different 'ethnic elements' in the occupation of southern Mesopotamia."[6] These ideas about the nature of the Ubaid phenomenon did not last. The term Ubaid itself is still used, but its meaning has changed over time.[7]

Joan Oates showed in 1960 that the Eridu and Hajji Muhammed styles were not distinct at all. Instead, they were part of the greater Ubaid phenomenon. She proposed a chronological framework that divides the Ubaid period in 4 phases. Other scholars later proposed phases 0 and 5.[8]

Scholars in the 1930s only knew a few Ubaid sites. These included the type site of Tell al-'Ubaid itself, Ur, and Tepe Gawra in the north. Since then, archaeologists found Ubaid material culture all over the ancient Near East. There are now Ubaid sites in the Amuq Valley in the northwest all the way to the Persian Gulf coast in the southeast.[7] Important research includes the many excavations in the Hamrin area in the 1970s. There, archaeologists found a complete Ubaid settlement at Tell Abada, and a really well-preserved house at Tell Madhur.[9] The excavation at Tell el-'Oueili in the 1980s reveiled occupation layers that were older than those from Eridu. This discovery pushed back the date for the earliest human occupation of southern Mesopotamia.[10]

Excavations along southcoast of the Persian Gulf provided a lot of evidence for contacts with Mesopotamia. The site of H3 in Kuwait, for example, provided the earliest evidence in the world for seafaring.[11] The explosion of archaeological research in Iraqi Kurdistan since the 2010s also led to a lot of new data on the Ubaid. For example, this research showed that cultural links between the Shahrizor Plain and the Hamrin area further south were stronger than those with the north.[12]

Climate and environment

Mesopotamia does not have local, high-resolution climate proxy records such as Soreq Cave. This makes it difficult to reconstuct the region's past climate. Even so, it is known that the environment during the sixth and fifth millennium BC was not the same as today. A more temperate climate settled in around 10,000 BC. Marshy and riverine areas transformed into floodplains and finally river banks with trees. The area south of Baghdad may have been inhabitable by humans in the eleventh millennium BC. Humans could have lived south of Uruk as early as the eighth millennium. This is much earlier than the oldest evidence human occupation in this area. The oldest known site in southern Mesopotamia (Tell el-'Oueili) dates to the Ubaid 0 period.[13] Archaeobotanical research in the Ubaid 0 levels at 'Oueili (6500-6000 BC) has indicated the presence of Euphrates poplar and sea clubrush, both indicative of a wetland environment.[14] As a result of changes in sea-level, the shoreline of the Persian Gulf during the Ubaid was different from that of today. At the beginning of the Ubaid, around 6500 BC, the shoreline at Kuwait may have ran slightly further south. During the subsequent 2.5 millenna, the shoreline moved further northward, up to the ancient city of Ur around 4000 BC.[15]

Date palms were present in southern Mesopotamia since at least the eleventh millennium BC, predating the earliest evidence for domesticated dates from Eridu by several millennia. Date palms require a perennial water source, again indicating that this period may have been wetter than today. Similarly, oak was present from the eighth millennium, but disappeared at around the same time that Ubaid material culture spread outward from southern Mesopotamia during the sixth millennium BC. It has been suggested that acquisition of high-quality wood may have played a role in this expansion.[13]

The available evidence in northern Mesopotamia points to a cooler and drier climate during the Hassuna and Halaf periods. During the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional (HUT), Ubaid and early Uruk periods, this developed into a climate characterised by stronger seasonal variation, heavy torrential rains and dry summers.[16]

Dating and geographical distribution

Ubaid and Ubaid-like material culture has been found over an immense area. Ubaid ceramics have shown up from Mersin in the west to Tepe Ghabristan [d] in the east, and from Norşuntepe and Arslantepe in the north to Dosariyah in the south along the Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia.[17] In this area, researchers have discerned considerable regional variation, indicating that the Ubaid was not a monolithic culture through time and space.[18]

The Ubaid period is most commonly divided in 6 phases, called Ubaid 0-5. Some of these phases equate with pottery styles that were, in earlier publications, considered to be distinct from Ubaid, but that are now considered to be part of the same phenomenon. Some of these styles, such as Hajji Muhammed (previously thought to be Ubaid 2) are now known to occur in Ubaid 3 contexts as well, thereby limiting their value as chronological markers. The relative chronology is based on the long stratigraphic sequences of sites such as Ur, Eridu and Tepe Gawra. The absolute chronology is harder to establish, mainly due to a lack of abundant radiocarbon dates coming from southern Mesopotamia.

| phase | alternative name | Northern Mesopotamia | date (BC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubaid 0 | Oueili phase | Early Pottery Neolithic | 6500-5900 / 6800-6200 |

| Ubaid 1 | Eridu style | Halaf | 5900-5200 / 6200-5500 |

| Ubaid 2 | Hajji Muhammad style | Halaf-Ubaid Transitional | 5200-5100 / 5500-5200 |

| Ubaid 3 | Tell al-'Ubaid style | Northern Ubaid | 5100-4900 / 5200-4600 |

| Ubaid 4 | Late Ubaid | Northern Ubaid | 4900-4350 / 5200-4600 |

| Ubaid 5 | Terminal Ubaid | Late Chalcolithic 1 | 4350-4200 / 4600-4200 |

Southern Mesopotamia

In the south, corresponding to the area that would later be known as Sumer, the entire Ubaid spans an immense period from ca. 6500 to 3800 BC.[18] It is here that the oldest known Ubaid site - Tell el-'Oueili - was found. In southern Iraq, no archaeological site has yet yielded remains older than Ubaid, However, this might be more a result of the fact that such ancient settlements are now buried deep under alluvial sediments. This was the case, for example, of the site of Hadji Muhammed, which was discovered only by accident.[21]

Central and northern Mesopotamia

In central and northern Iraq, the Ubaid was preceded by the Hassuna and Samarra cultures. The Ubaid may have developed out of the latter.[22] In northern Syria and southeastern Turkey, the Ubaid follows upon the Halaf period, and a relatively short Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period (HUT) dating to c. 5500-5200 BC has been proposed as well.[17] HUT pottery assemblages displayed both typically Ubaid and Halaf characteristics.[23] The relations between these periods - or cultures - is complex and not yet fully understood, including how and when exactly the Ubaid started to appear in northern Mesopotamia. To resolve these issues, modern scholarship tends to focus more on regional trajectories of change where different cultural elements from the Halaf, Samarra, or Ubaid - pottery, architecture, and so forth - could co-exist. This makes it increasingly hard to define an occupation phase at a site as, for example, purely Ubaid or purely Halaf.[17][24]

In northern Mesopotamia, Ubaid characteristics only start to appear in Ubaid 2-3, i.e. toward the end of the sixth millennium BC, so that the entire Ubaid period would be much shorter. For Syria, a range of 5300-4300 BC has been suggested.[25] However, some scholars have argued that the interaction between the originally southern Mesopotamian Ubaid and the north started already during Ubaid 1-2.[17]

Persian Gulf

Ubaid pottery started to appear along the Persian Gulf coast toward the end of the sixth millennium BC, reaching a peak around 5300 BC and continuing into the fifth millennium. Coastal sites where Ubaid pottery has been found include Bahra 1 and H3 in Kuwait, Dosariyah in Saudi Arabia, and also island sites such as Dalma Island in the United Arab Emirates. Ubaid pottery has also been found further inland along the central Gulf coast at sites like Ain Qannas, suggesting that the pottery may have been traded and valued in and of itself, rather than just being a container for some other commodity. This suggestion is reinforced by locally-produced pottery imiting Ubaid wares found at Dosariyah. It is unclear which products were exchanged for the pottery. Suggestions include foodstuffs (dates), semi-precious materials, jewellery (made from pearl and shell), animal products, and livestock. Notably, the degree of cultural interaction between the Ubaid and local Neolithic communities is much stronger in the area of Kuwait than further south, up to the point that it has been suggested that Mesopotamians may have actually lived (part of the year) at sites like H3 and Bahra 1.[26] Small objects such as labrets, tokens, clay nails and small tools that may have had cosmetic use, and that are known from southern Mesopotamian sites also occur on sites along the Gulf coast, notably the sites in Kuwait.[27]

Conversely, there is also evidence for Arabian Neolithic material in southern Mesopotamia. It has been noted that certain types of flint arrowheads found at Ur show clear resemblance with the Arabian Bifacial Tradition. Arabian Coarse Ware has been found at the sites of 'Oueili and Eridu. As at the sites in Kuwait, it may have been possible that Arabian Neolithic persons lived in southern Mesopotamia.[27]

Description

Ubaid culture is characterized by large unwalled village settlements, multi-roomed rectangular mud-brick houses and the appearance of the first temples of public architecture in Mesopotamia, with a growth of a two tier settlement hierarchy of centralized large sites of more than 10 hectares surrounded by smaller village sites of less than 1 hectare. Domestic equipment included a distinctive fine quality buff or greenish colored pottery decorated with geometric designs in brown or black paint. Tools such as sickles were often made of hard fired clay in the south, while in the north stone and sometimes metal were used. Villages thus contained specialised craftspeople, potters, weavers and metalworkers, although the bulk of the population were agricultural labourers, farmers and seasonal pastoralists.

During the Ubaid Period (5000–4000 BC), the movement towards urbanization began. "Agriculture and animal husbandry [domestication] were widely practiced in sedentary communities".[28] There were also tribes that practiced domesticating animals as far north as Turkey, and as far south as the Zagros Mountains.[28] The Ubaid period in the south was associated with intensive irrigated hydraulic agriculture, and the use of the plough, both introduced from the north, possibly through the earlier Choga Mami, Hadji Muhammed and Samarra cultures.

The archaeological record shows that Arabian Bifacial/Ubaid period came to an abrupt end in eastern Arabia and the Oman peninsula at 3800 BC, just after the phase of lake lowering and onset of dune reactivation.[29] At this time, increased aridity led to an end in semi-desert nomadism, and there is no evidence of human presence in the area for approximately 1,000 years, the so-called "Dark Millennium".[30] The increased aridity might have been due to the 5.9 kiloyear event at the end of the Older Peron.[29]

Society

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

The Ubaid period as a whole, based upon the analysis of grave goods, was one of increasingly polarized social stratification and decreasing egalitarianism. Bogucki describes this as a phase of "Trans-egalitarian" competitive households, in which some fall behind as a result of downward social mobility. Morton Fried and Elman Service have hypothesised that Ubaid culture saw the rise of an elite class of hereditary chieftains, perhaps heads of kin groups linked in some way to the administration of the temple shrines and their granaries, responsible for mediating intra-group conflict and maintaining social order. It would seem that various collective methods, perhaps instances of what Thorkild Jacobsen called primitive democracy, in which disputes were previously resolved through a council of one's peers, were no longer sufficient for the needs of the local community.

Ubaid culture originated in the south, but still has clear connections to earlier cultures in the region of middle Iraq. The appearance of the Ubaid folk has sometimes been linked to the so-called Sumerian problem, related to the origins of Sumerian civilisation. Whatever the ethnic origins of this group, this culture saw for the first time a clear tripartite social division between intensive subsistence peasant farmers, with crops and animals coming from the north, tent-dwelling nomadic pastoralists dependent upon their herds, and hunter-fisher folk of the Arabian littoral, living in reed huts.

Stein and Özbal describe the Near East oecumene that resulted from Ubaid expansion, contrasting it to the colonial expansionism of the later Uruk period. "A contextual analysis comparing different regions shows that the Ubaid expansion took place largely through the peaceful spread of an ideology, leading to the formation of numerous new indigenous identities that appropriated and transformed superficial elements of Ubaid material culture into locally distinct expressions."[31]

The earliest evidence for sailing has been found in Kuwait indicating that sailing was known by the Ubaid 3 period.[32]

There is some evidence of warfare during the Ubaid period although it is extremely rare. The "Burnt Village" at Tell Sabi Abyad could be suggestive of destruction during war but it could also have been due to other causes, such as wildfire or accident. Ritual burning is also possible since the bodies inside were already dead by the time they were burned. A mass grave at Tepe Gawra contained 24 bodies apparently buried without any funeral rituals, possibly indicating it was a mass grave from violence. Copper weapons were also present in the form of arrow heads and sling bullets, although these could have been used for other purpose; two clay pots recovered from the era have decorations showing arrows used for the purpose of hunting. A copper axe head was made in the late Ubaid period, which could have been a tool or a weapon.[33]

During the late Ubaid period around 4500–4000 BC, there was some increase in social polarization, with central houses in the settlements becoming bigger. But there were no real cities until the later Uruk period.

See also

Citations

- ^ Hall & Woolley 1927.

- ^ Adams Jr. & Wright 1989.

- ^ McMahon, A. (2014). "'Ubaid-Kultur, -Keramik". Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Band, 14. Band. pp. 261–265. ISBN 978-3-11-041761-6. OCLC 985433875.

- ^ Matthews, Roger, Dr (2002). Secrets of the dark mound : Jemdet Nasr 1926-1928. Warminster: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 0-85668-735-9. OCLC 50266401.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Potts, D.T. (1986). "A contribution to the history of the term 'Ǧamdat Naṣr'". In Finkbeiner, Uwe; Röllig, Wolfgang (eds.). Ǧamdat Naṣr: period or regional style? : papers given at a symposium held in Tübingen, November 1983. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 17–32. ISBN 978-3-88226-262-9. OCLC 16224643.

- ^ a b Carter, Robert A.; Philip, Graham (2010). "Deconstructing the Ubaid". Beyond the Ubaid : transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East (PDF). Robert A. Carter, Graham Philip, University of Chicago. Oriental Institute, Grey College. Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0. OCLC 646401242.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (2010). "The term "Hajji Muhammad": a re-evaluation". Beyond the Ubaid : transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East (PDF). Robert A. Carter, Graham Philip, University of Chicago. Oriental Institute, Grey College. Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 163–168. ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0. OCLC 646401242.

- ^ Roaf, Michael (1982). "The Hamrin sites". Fifty years of Mesopotamian discovery : the work of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1932-1982. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. pp. 40–47. ISBN 0-903472-05-8. OCLC 10923961.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Huot, Jean-Louis; Vallet, Régis (1990). "Les Habitations à salles hypostyles d'époque Obeid 0 de Tell El'Oueili". Paléorient. 16 (1): 125–130. doi:10.3406/paleo.1990.4527.

- ^ Carter, Robert (2006). "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC". Antiquity. 80 (307): 52–63. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0009325X. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 162674282.

- ^ Carter, Robert; Wengrow, David; Saber, Saber Ahmed; Hamarashi, Sami Jamil; Shepperson, Mary; Roberts, Kirk; Lewis, Michael P.; Marsh, Anke; Carretero, Lara Gonzalez; Sosnowska, Hanna; D'Amico, Alexander (2020). "The Later Prehistory of the Shahrizor Plain, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: Further Investigations at Gurga Chiya and Tepe Marani". Iraq. 82: 41–71. doi:10.1017/irq.2020.3. ISSN 0021-0889. S2CID 228904428.

- ^ a b Altaweel, Mark; Marsh, Anke; Jotheri, Jaafar; Hritz, Carrie; Fleitmann, Dominik; Rost, Stephanie; Lintner, Stephen F.; Gibson, McGuire; Bosomworth, Matthew; Jacobson, Matthew; Garzanti, Eduardo (2019). "New Insights on the Role of Environmental Dynamics Shaping Southern Mesopotamia: From the Pre-Ubaid to the Early Islamic Period" (PDF). Iraq. 81: 23–46. doi:10.1017/irq.2019.2. ISSN 0021-0889. S2CID 200071451.

- ^ Wilkinson, Tony J. (2012-12-01). Wetland Archaeology and the Role of Marshes in the Ancient Middle East. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199573493.013.0009.

- ^ Kennett, Douglas J.; Kennett, James P. (2006). "Early State Formation in Southern Mesopotamia: Sea Levels, Shorelines, and Climate Change". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 1 (1): 67–99. doi:10.1080/15564890600586283. ISSN 1556-4894. S2CID 140187593.

- ^ Hole, Frank (1997). "Paleoenvironment and Human Society in the Jezireh of Northern Mesopotamia 20 000-6 000 BP". Paléorient (in French). 23 (2): 39–49. doi:10.3406/paleo.1997.4651. ISSN 0153-9345.

- ^ a b c d Baldi, Johnny Samuele (2020). "Evolution as a way of intertwining: regional approach and new data on the Halaf-Ubaid transition in Northern Mesopotamia". In Iamoni, Marco (ed.). Proceedings of the 5th "Broadening Horizons" Conference (Udine 5-8 June, 2017). Trieste. pp. 71–87. ISBN 978-88-5511-046-4. OCLC 1200195553.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Carter, Robert A.; Philip, Graham (2010). "Deconstructing the Ubaid". Beyond the Ubaid : transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East (PDF). Robert A. Carter, Graham Philip, University of Chicago. Oriental Institute, Grey College. Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0. OCLC 646401242.

- ^ Pournelle, Jennifer R. (2003). Marshland of cities: Deltaic landscapes and the evolution of early Mesopotamian civilization.

- ^ Harris, Samuel Lee (2021). "Public Works and Private Work on the Threshold of Complexity: The Production and Use of Space at Late Chalcolithic 1 Tell Surezha, Iraq - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ McMahon, A. (2014). "'Ubaid-Kultur, -Keramik". Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Band, 14. Band. pp. 261–265. ISBN 978-3-11-041761-6. OCLC 985433875.

- ^ Peasnall, Brian (2002). "Ubaid". In Peregrine, Peter N.; Ember, Melvin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 372–390. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0023-0_37. ISBN 978-1-4684-7135-9. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ Özbal, Rana (2012-11-21). "The Chalcolithic of Southeast Anatolia". In McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0008.

- ^ Campell, Stuart (2007). "Rethinking Halaf Chronologies". Paléorient. 33 (1): 103–136. doi:10.3406/paleo.2007.5209.

- ^ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The archaeology of Syria : from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79230-4. OCLC 50322834.

- ^ Carter, Robert (2018). "Globalising Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic and the 'Ubaid". In Frachetti, Michael D.; Boivin, Nicole (eds.). Globalization in Prehistory: Contact, Exchange, and the 'People Without History'. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–79. ISBN 978-1-108-42980-1. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ a b Carter, Robert (2020). "The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1111/aae.12145. ISSN 0905-7196. S2CID 213877028.

- ^ a b Pollock 1999.

- ^ a b Parker et al. 2017.

- ^ Uerpmann 2003, pp. 74–81.

- ^ Stein & Özbal 2006.

- ^ Carter 2006b.

- ^ Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy warriors at the dawn of history. Routledge. p. 28-29.

References

- Adams Jr., Robert McCormick; Wright, Henry Tutwiler (1989). Henrickson, Elizabeth F.; Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.). Upon this Foundation: The ʻUbaid Reconsidered : Proceedings from the ʻUbaid Symposium, Elsinore, May 30th-June 1st 1988. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788772890708.

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521796668.

- Ashkanani, Hasan J.; Tykot, Robert H.; Al-Juboury, Ali Ismail; Stremtan, Ciprian C. (2019-11-24). "A characterisation study of Ubaid period ceramics from As-Sabbiya, Kuwait, using a non-destructive portable X-Ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectrometer and petrographic analyses". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (8). Petřík, Jan; Slavíček, Karel: 3–18. doi:10.1111/aae.12143.

- Bibby, Thomas Geoffrey (2008-08-27). Looking for Dilmun. United Kingdom: Knopf. ISBN 9780394434001.

- Bogucki, Peter (1990). The Origins of Human Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 1577181123.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9781614510352.

- Carter, Robert (2006-04-20). Philip, G. (ed.). Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. United Kingdom: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 9781885923660.

- Carter, Robert (March 2006). Carver, Martin (ed.). "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC". Antiquity. 80 (307): 52–63. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0009325X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Crawford, Harriet Elizabeth Walston (1998-03-12). Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbours. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521586795.

- Crawford, Harriet Elizabeth Walston (2004-09-16). Sumer and the Sumerians. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Cambridge University Press (CUP). ISBN 9780521533386.

- Hall, Harry Reginald; Woolley, Charles Leonard (1927). Al-'Ubaid: A Report on the Work Carried Out at Al-'Ubaid for the British Museum in 1919 and for the Joint Expedition in 1922-3. ASIN B00086M1HG.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006-09-27). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. ISBN 9781134520626.

- Khalidi, Lamya; Gratuze, Bernard (2016-10-18). "The growth of early social networks: New geochemical results of obsidian from the Ubaid to Chalcolithic Period in Syria, Iraq and the Gulf". Journal of Archaeological Science. 9. Elsevier: 743–757. Bibcode:2016JArSR...9..743K. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.06.026.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East, C. 3000-330 BC. Routledge history of the ancient world. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415167635.

- Matthews, Roger (2002). Secrets of the Dark Mound: Jemdet Nasr 1926-1928 (Report). Iraq archaeological reports. Vol. 6. Warminster: BISI. ISBN 9780856687358. ISSN 0956-2907.

- Parker, Adrian G.; Goudie, Andrew S.; Stokes, Stephen; White, Kevin; Hodson, Martin J.; Manning, Michelle; Kennet, Derek (2017-01-20). "A record of Holocene climate change from lake geochemical analyses in southeastern Arabia" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 66 (3). Elsevier: 465–476. Bibcode:2006QuRes..66..465P. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.07.001.

- Pollock, Susan (1999-05-20). Wright, Rita P. (ed.). Ancient Mesopotamia. Case Studies in Early Societies. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521575683.

- Pollock, Susan; Bernbeck, Reinhard (2009-02-09). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. Penton. ISBN 9781405137232.

- Raux, Franck (1931). "AO 14281". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1932a). "AO 15327". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236. Archived from the original on 2015-04-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1932d). "AO 15334". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1932b). "AO 15338". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1932c). "AO 15388". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1989a). "AO 29598". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236. Archived from the original on 2021-09-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1989d). "AO 29611". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236. Archived from the original on 2021-09-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Raux, Franck (1989c). "AO 29616". Département des Antiquités orientales. Musée du Louvre (in French). SALLE 236. Archived from the original on 2021-06-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Roux, Georges (1966). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140125238.

- Stiebing Jr., William H. (2016-07-01). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. MySearchLab Series (revised ed.). Longman. ISBN 9781315511160.

- Stein, Gil; Özbal, Rana (2006). "A Tale of Two Oikumenai: Variation in the Expansionary Dynamics of Ubaid and Uruk Mesopotamia". In Stone, Elizabeth C. (ed.). Settlement and Society: Ecology, urbanism, trade and technology in Mesopotamia and Beyond. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research Press. pp. 329–343.

- Uerpmann, Margarethe (2003). "The Dark Millennium—Remarks on the final Stone Age in the Emirates and Oman". In Potts, Daniel T.; Al Naboodah, Hasan; Hellyer, Peter (eds.). Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates. Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Archaeology of the U.A.E. United Kingdom: Trident Press. ISBN 9781900724982.

- Wittfogel, Karl August (2010-09-07). Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power. Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power. United Kingdom: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780835782562.

Further reading

- Charvát, Petr (2002). Mesopotamia Before History (revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781134530779.

- Martin, Harriet P. (1982). "The Early Dynastic Cemetery at al-'Ubaid, a Re-Evaluation". Iraq. 44 (2): 145–185. doi:10.2307/4200161. JSTOR 4200161.

- Mellaart, James (1975). The Neolithic of the Near East. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684144832.

- Moore, A. M. T. (2002). "Pottery Kiln Sites at al 'Ubaid and Eridu". Iraq. 64: 69–77. doi:10.2307/4200519. JSTOR 4200519.

- Nissen, Hans Jörg (1990). The Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000–2000 B.C.. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226586588.

External links

- British Museum, Trustees of the (2008-06-03). "Stone statue of Kurlil". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-10-18.

- British Museum, Trustees of the (2007-11-13). "Copper figure of a bull". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13.

- British Museum, Trustees of the (2008-06-06). "Ubaid visit and photos". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 2008-08-01.