Zeytinburnu

Zeytinburnu | |

|---|---|

District and municipality | |

Dikilitaş neighborhood of Zeytinburnu | |

Map showing Zeytinburnu District in Istanbul Province | |

| Coordinates: 40°58′59″N 28°53′59″E / 40.98306°N 28.89972°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Istanbul |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ömer Arısoy (AKP) |

Area | 12 km2 (5 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 292,616 |

| • Density | 24,000/km2 (63,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Area code | 0212 |

| Website | zeytinburnu |

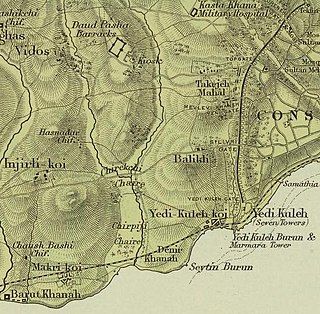

Zeytinburnu (literally, Olive Cape) is a municipality and district of Istanbul Province, Turkey.[2] Its area is 12 km2,[3] and its population is 292,616 (2022).[1] It is a working-class area on the European side of Istanbul, Turkey, on the shore of the Marmara Sea just outside the walls of the ancient city, beyond the fortress of Yedikule.

Geography

[edit]Zeytinburnu is located on the part of Çatalca peninsula that is apart from historical peninsula with Walls of Constantinople and overlooks to the Marmara Sea in İstanbul. Its altitude generally increases from south to north, and in south districts (Sümer, Nuripaşa, Kazlıçeşme etc.) embankments, alluvium and former stream beds lay while in north districts (Beştelsiz, Telsiz, Maltepe etc.) wearing surfaces of Bakırköy member (limestone with intercalated clay) lay.[4]

In addition Zeytinburnu is next to the west part of the North Anatolian Fault, according to KOERI-UDİM possibility of an earthquake with M=7.0 in the next 50 years is 60.2% so Zeytinburnu is seismically at risk.[5]

According to the study carried out in 2024, amount of tree cover in Zeytinburnu is 151 Hectare, and its tree cover's percentage is 13.02%. The tree cover of Zeytinburnu has been mostly limited to its graveyards recently, so this district presents the appearance of a concrete jungle.[6]

Composition

[edit]There are 13 neighbourhoods in Zeytinburnu District:[7]

- Beştelsiz

- Çırpıcı

- Gökalp

- Kazlıçeşme

- Maltepe

- Merkezefendi

- Nuripaşa

- Seyitnizam

- Sümer

- Telsiz

- Veliefendi

- Yenidoğan

- Yeşiltepe

History

[edit]

Zeytinburnu was a fortress and settlement known as Kyklobion (Greek: Κυκλόβιον) or Strongylon (Στρογγυλόν) during the Byzantine period, its name referring to the circular shape of the fortress.[8]

The fortress was built in Late Antiquity as part of a series of strongholds that guarded the coastal road leading to Constantinople. It is first attested during the reign of Justinian I (527–565). Kyklobion was used as the landing-site of the Arab armies on both of their assaults on Constantinople, in 674 and in 717.[8] In the early 8th century, the iconodule Saint Hilarion was kept prisoner in the local monastery on the orders of Emperor Leo V the Armenian (r. 813–820).[8] The site is again, and for the last time in Byzantine times, mentioned in a property deed of 1388.[8]

After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the name Kyklobion was transferred to the Yedikule Fortress by the local Greeks, and the original site was abandoned. Ruins of the original circular fortress survived until the 19th century, where the Austrian traveller Hammer-Purgstall saw them. Its name at the time was called in Greek Elaion Akra, "Cape of the Olive Trees"; the modern Turkish name has the same meaning.[8]

From the early 19th century onwards Zeytinburnu was an industrial village, centred on the leather industry of the area called Kazlıçeşme, which being on the coast with a good water supply was well suited to leather production. (the area was named for a fountain with a goose carved into the stonework, the fountain is still in existence). Up until the mid-20th century the residents were an urban mix of Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Jews and Turks and still today the Yedikule Surp Pırgiç Armenian Hospital is active in Kazlıçeşme, and has a museum in the grounds.[9]

The character of Zeytinburnu changed when a large wave of immigrants from Anatolia came and settled there from 1950 on. Zeytinburnu is an important lesson for city planning in Turkey, because it was one of the first Gecekondu districts. In other words, most of the buildings were built illegally, without infrastructure, and without any aesthetical concern. In the 1960s legislation was passed to prevent this type of building but by then this type of development had become unstoppable. At first these were little brick-built single storey cottages. From the 1970s onwards the little houses were replaced by multi-storey concrete apartment blocks built in rows with no space in between. In most cases the ground floor was used as a small textile workshop, and thus Zeytinburnu became a bustling industrial area with a large residential population living above the workshops. All this was still illegal, unplanned and lacked the infrastructure and the aesthetic appeal. After a heavy rain the streets would run with dirty water for days.

Mosaic floor tiles were discovered during the restoration of the Zeytinburnu Kazlıçeşme Cultural Center. The mosaics date to the Late Roman and early Byzantine period.[10]

Historical places

[edit]- Balıklı

- Holy Spring

- Balıklı Church

- Balıklı Greek Hospital

- Çırpıcı Meadows

- Kirazlıçeşme Fatih Mosque

- Hacı Mahmud Ağa Dervish Lodge

- Kazlı Çeşme (Goose Fountain)

- Merkez Efendi Dervish Lodge

- Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha Masjid

- Perişan Baba Dervish Lodge

- Seyyid Nizam Dervish Lodge

- Walls of Constantinople

- Yedikule Surp Pırgiç Armenian Hospital

- Takkeci İbrahim Ağa Mosque

- Yenikapı Mevlevîhane

- Zeytinburnu Military Hospital

- Cemeteries in Zeytinburnu

Zeytinburnu today

[edit]

The leather industry has largely moved out to Tuzla now but the rows of six-storey blocks of housing and textiles remain. Although some improvements have been made to the streets and drainage, the area still has a stereotypical reputation for being the home of tough men and uncontrollable youths who drive around in cars blasting out pop music at high-volume. This is possibly exaggerated nowadays, and steps are being taken to smarten up the area. Most residents are working class, recent migrants from Anatolia, typically lacking in education. However, the younger generations are more educated thus changing the demographic shape of Zeytinburnu.

To integrate the district with the rest of Istanbul, the municipality has improved the transportation by extending the modern tram line to Zeytinburnu, and the main tram station is now at the intersection of the metro line leading to Atatürk International Airport and Aksaray and fast tram lines leading to Istanbul's inter-city coach station and the old city in Eminönü. Moreover, Zeytinburnu has a station on the suburban railway line Sirkeci-Halkalı. Other important projects have improved the transportation, life quality and the economy of the district. Olivium Outlet Center was opened in 2000,[12] a modern shopping mall with cinemas, with many shops specializing in factory surpluses, bringing new shopping opportunities for the people of Zeytinburnu and surrounding districts. The mall attracts many visitors on weekends.

There is an Alevi community served by the Erikli Baba Cemevi.[13] There are large minority groups of Kazakhs and Turkmens,[14] who generally work in the textile industry, contributing to the Turkish economy. The Zeytinburnu-based NASCO NASREDDIN HOLDING A.S. was categorized as an Al-Qaeda ally by the United Nations.[15][16][17][18][19] It was involved in terrorist financing.[citation needed] The Romanian government legislated this status for Zeytinburnu Nasco Nasreddin Holding A. S., as well as the Slovakian government.[20][21][22]

On 10 December 2014, in Zeytinburnu, an assassin killed the anti-Uzbekistan government Islamist Uzbek Imam Shaykh Abdullah Bukhoroy (Abdullah Bukhari).[23][24][25][26][27][28] It took place outside of a Madrassa.[29]

The Turkish-run English language BGNNews news agency reported that the Turkish Meydan newspaper discovered that Uyghur fighters joining the Islamist terrorist organization ISIL were being helped by businessman Nurali T., who led a network based in Zeytinburnu, which produced counterfeit Turkish passports numbering up to 100,000 distributed to Uyghurs from China to help them go to Turkey form where they would enter Iraq and Syria to join ISIL. Uyghurs from China would travel to Malaysia via Cambodia and Thailand and then to Turkey, since a visa is not needed for travel between Turkey and Malaysia, then stay at locations in Istanbul, and then go to Iraq and Syria by traveling to southeastern Turkey. The information was revealed by AG who participates in the network, who noted that even though Turkish authorities are able to detect the fake passports they do not deport the Uyghurs and allow them into Turkey. AG said that: “Turkey has secret deals with the Uighurs. The authorities first confiscate the passports but then release the individuals.”[30]

Seven Uyghur restaurant workers, who provided money to the perpetrator of the 2017 Istanbul nightclub attack for his taxi fare, were arrested in Zeytinburnu. The restaurant was owned by Şemseddin Dursun.[31] The Seferoğlu Sokak-based Uyghurs in Zeytinburnu[32] aided the attacker when he fled the nightclub.[33][34] As a result, Zeytinburnu became the site of over 50 police sweeps against "East Turkistanis" (Uyghurs), Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Uzbeks. Zeytinburnu is infamous for being used by Syria-destined jihadists as a transit point.[35] An Uzbek national committed the nightclub attack according to the Turkish police.[36] Turkish media said he was from the "East Turkestan" wing of ISIS.[37][38] Erdoğan's government has deliberately facilitated the travel of Jihadist Uyghurs through Zeytinburnu, with Turkish intelligence involved and the nightclub massacre at Reina is a result of this.[39] Turkey nabbed Abuliezi Abuduhamiti and Omar Asim, both Uyghurs.[40]

There are more than 100,000 unregistered people of Xinjiang and Central Asian origin in Zeytinburnu.[41] Zeytinburnu, among other districts such as Küçükçekmece, Başakşehir, Bağcılar, Gaziosmanpaşa, Esenler, Bayrampaşa, and Fatih, is home to many refugees of Syrian origin.[42]

-

General view

-

Zeytinburnu Cultural and Art Center

-

Armenian Hospital

-

The community mosque of Turks of Western Thrace

-

Hat Boyu Street and leather shops

-

Belgrad Gate

-

Holy Fishes in Greek Church Balıklı

Environment

[edit]Zeytinburnu is a very crowded county of İstanbul, so it undergoes a dense housing. Around coastal areas of Zeytinburnu the government ignored the court decisions and committed gentrification and ecocide. While public lands next to the coast were transformed to residences, between Zeytinburnu and its coast a concrete wall was constructed.[43]

Sports

[edit]Teams

[edit]

- Football

Zeytinburnuspor, a top-flight football team in the early 1990s, is now languishing in the minor leagues. Arif Erdem and Emre Belözoğlu started their careers here. Matjaž Cvikl (1967–1999) from the Slovenia national football team also played there.

The women's football team played once in the Turkish Women's First Football League.

- Ice hockey

The 2010-established men's ice hockey team of Zeytinburnu Belediyespor finished the 2013–14 Turkish Ice Hockey Super League (TBHSL) season as the runner-up. They became the champion in the following 2014–15 and 2015–16 seasons.[44][45]

Venues

[edit]Zeytinburnu Stadium with a total capacity of 16,000 people, is home to the football teams of Zeytinburnu.[46]

The Zeytinburnu Ice Rink, opened in 2016, is a mobile ice rink, which hosted the home 2015–16 season matches of the Zeytinburnu Belediyespor ice hockey team.[47]

Town twinning

[edit]Zeytinburnu is twinned with:

Narimanov, Azerbaijan

Narimanov, Azerbaijan Kuala, Azerbaijan

Kuala, Azerbaijan Beit Hanoun, Palestinian territories

Beit Hanoun, Palestinian territories Semey, Kazakhstan

Semey, Kazakhstan Taraz, Kazakhstan

Taraz, Kazakhstan Shkodra, Albania

Shkodra, Albania

Mayor Government of Zeytinburnu

[edit]- 1984–1989 – Muzaffer Çavuşoğlu Anavatan Party

- 1989–1994 – Hasan Yılmaz SHP

- 1994–1995 Adil Emecan DSP

- 1995–1999 – Adil Emecan Anavatan Party

- 1999–2001 Murat Aydın Fazilet Party

- 2001–2019 – Murat Aydın AK Party

- 2019–present – Ömer Arısoy AK Party

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Büyükşehir İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Sönmez, Mehmet Emin. "Coğrafi Bilgi Sistemleri (CBS) Tabanlı Deprem Hasar Riski Analizi: Zeytinburnu (İstanbul) Örneği". www.dergipark.org. Türk Coğrafya Dergisi.

- ^ Deprem ve Zemin İnceleme Müdürlüğü, Deprem ve Zemin İnceleme Müdürlüğü. "İSTANBUL İLİ BAHÇELİEVLER-BAKIRKÖY GÜNGÖREN-ZEYTİNBURNU İLÇELERİ HEYELAN FARKINDALIK KİTAPÇIĞI" (PDF). www.ibb.istanbul/. İBB.

- ^ Turan, Tunahan Uğur. "A Comparative Urban Ecological Study on Bakırköy and Zeytinburnu". www.researchgate.com. Researchgate. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ Mahalle, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Külzer, Andreas (2008). Tabula Imperii Byzantini: Band 12, Ostthrakien (Eurōpē) (in German). Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 484–485. ISBN 978-3-7001-3945-4.

- ^ "Official homepage" (in Turkish). Surp Pırgiç Ermeni Hastanesi. 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ "Roman and Byzantine era mosaics in Kazlıçeşme". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ "Official homepage". Zeytinburnu District Portal. 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "Official homepage". Olivium Outlet Center. 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "Official homepage" (in Turkish). Erikli Baba Cemevi. 2010.

- ^ "Official homepage" (in Turkish). Easternturkistan Migration Association, Zeytinburnu. 2010.

- ^ "Redirecting". Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Security Council Committee Adds Twenty-Five Individuals and Entities to ITS List". Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE REMOVES ONE INDIVIDUAL, 12 ENTITIES FROM CONSOLIDATED LIST | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases".

- ^ "SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ADDS TWENTY-FIVE INDIVIDUALS AND ENTITIES TO ITS LIST | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases".

- ^ "United Nations Information Service Vienna".

- ^ Romania (May 2004). Monitorul oficial al României: Legi, decrete, hotărîri și alte acte. Parlamentul României, Adunarea Deputaților. p. 26.

- ^ Slovakia (2003). Zbierka zákonov Slovenskej republiky. Ministerstvo spravodlivosti Slovenskej republiky. p. 1436.

- ^ Slovakia (2003). Zbierka zákonov Slovenskej republiky. Ministerstvo spravodlivosti Slovenskej republiky. p. 1052.

- ^ "Radical Uzbek Imam Shot Dead In Istanbul". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Turkey: Russian citizen detained in connection with Uzbek imam assassination in Istanbul – Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Turkey: "Uzbek imam" murder video emerges – Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Alleged organizers, killers of Uzbek imam in Turkey arrested, named – Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Four more dissident Uzbeks are on assasination [sic] list -report – Asia-Pacific – Worldbulletin News". World Bulletin. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Uzbekistan: Swedish Trial Features Testimony About Alleged International Assassin Network". EurasiaNet.org. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Have Russian hitmen been killing with impunity in Turkey?". BBC News Magazine. 13 December 2016.

- ^ "ISIL recruits Chinese with fake Turkish passports from Istanbul". Istanbul. BGNNews. 9 April 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Bozkurt, Abdullah [@abdbozkurt] (4 January 2017). "Şemseddin Dursun, the owner of Uyghur restaurant where the night-club attacker allegedly picked up a cab fare, denies all accusations" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Bozkurt, Abdullah [@abdbozkurt] (3 January 2017). "Then, he got into the second cab, driven to an alley 'Şuayip Seferoğlu Sokak' where a Uyghur Restaurant located in Zeytinburnu district" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Stojanovic, Dusan (4 January 2017). "Turkey identifies gunman in Istanbul nightclub shooting". Associated Press. ISTANBUL.

- ^ Bozkurt, Abdullah [@abdbozkurt] (3 January 2017). "He paid off the driver with the money he borrowed from the Uyghur employees of this restaurant. Police detained seven restaurant workers" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ ULUDAĞ, NİHAT (4 January 2017). "Reina'ya saldıran teröristin katliam sonrası rotası..." HABER İÇİN HABERTÜRK (in Turkish).

- ^ "Turkish media releases video of suspected nightclub gunman, claims he is Chinese Uygur Muslim". South China Morning Post. 3 January 2017.

- ^ Robson, Steve; Rkaina, Sam; Bishop, Rachel; Milanian, Keyan (2 January 2017). "Istanbul nightclub ISIS attack: Recap as ISIS claims responsibility for gun attack that left 39 dead". The Mirror.

- ^ Wellman, Alex; Robson, Steve; Bishop, Rachel (1 January 2017). "First picture of Istanbul terror suspect after gunman 'screamed Allahu Akbar' as he slaughtered 39 in Turkish nightclub". The Mirror.

- ^ Bozkurt, Abdullah (3 January 2017). "[OPINION] How Erdoğan empowered jihadists from China". Turkish Minute.

- ^ "Turkey arrests two Chinese Uighurs over Istanbul nightclub attack". REUTERS. 14 January 2017.

- ^ Gurcan, Metin (13 January 2017). "'Devotees of Death' headed for Turkey". Al-Monitor.

- ^ HAYATA DESTEK (31 August 2013). Syrian Refugees in Turkey (PDF) (Report). SUPPORT TO LIFE. pp. 4–5.

- ^ GÜVEMLİ, ÖZLEM. "Kazlıçeşme sahiline beton duvar!". www.sozcu.com.tr/. Sözcü. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Zeytinburnu Belediyesi Buz Hokeyi Takımı Şampiyon Oldu". Milliyet (in Turkish). 5 June 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Buz Hokeyinde Şampiyon ZEwytinburnu Belediye". Milliyet (in Turkish). 1 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Zeytinburnu Stadi". worldstadiums.com. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Türk Buz Hokeyi'nde Bir İlk". Son Dakika (in Turkish). 6 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

External links

[edit]- District governor's official website (in Turkish)

- District municipality's official website (in English)