Zemun

Zemun

Земун (Serbian) | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view of Zemun from Gardoš Tower | |

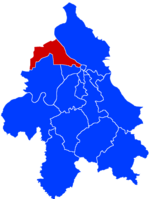

Location of Zemun within the city of Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°51′N 20°24′E / 44.850°N 20.400°E | |

| Country | |

| City | Belgrade |

| Settlements | 4 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gavrilo Kovačević (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 99.42 km2 (38.39 sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 149.77 km2 (57.83 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Municipality | 177,908[3] |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11080 |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

| Website | www |

Zemun (Serbian Cyrillic: Земун, pronounced [zěmuːn]; Hungarian: Zimony) is a municipality in the city of Belgrade, Serbia. Zemun was a separate town that was absorbed into Belgrade in 1934. It lies on the right bank of the Danube river, upstream from downtown Belgrade. The development of New Belgrade in the late 20th century expanded the continuous urban area of Belgrade and merged it with Zemun.

The town was conquered by the Kingdom of Hungary in the 12th century and in the 15th century it was given as a personal possession to the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. After the Serbian Despotate fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1459, Zemun became an important military outpost. Its strategic location near the confluence of the Sava and the Danube placed it in the center of the continued border wars between the Habsburg and the Ottoman empires. The Treaty of Passarowitz of 1718 finally placed the town into Habsburg possession, the Military Frontier was organized in the region in 1746, and the town of Zemun was granted the rights of a military commune in 1749. In 1777, Zemun had 6,800 residents, half of which were ethnic Serbs, while another half of the population was composed of Germans, Hungarians and Jews. With the abolishment of the Military Frontier in 1881, Zemun and the rest of the eastern Srem was included into Syrmia County of Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, part of Austria-Hungary. Following Austro-Hungarian defeat in World War I, Zemun returned to Serbian control on November 5, 1918 and became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Kingdom of Yugoslavia).

According to the 2022 census results, the municipality of Zemun has a population of 177,908 inhabitants. Apart from the Zemun proper, the municipality includes suburbs of Batajnica, Ugrinovci, Zemun Polje and Nova Galenika to the northwest.

Name

[edit]In ancient times, the Celtic and Roman settlement was known as Taurunum. The Frankish chroniclers of the Crusades mentioned it as Mallevila, a toponym from the 9th century. This was also a period when the Slavic name Zemln was recorded for the first time. Believed to be derived from the word zemlja, meaning soil, it was a basis for all other future names of the city: modern Serbian Земун (Cyrillic) or Zemun (Latin), Za·munt (Romanian), Hungarian Zimony and German Semlin, which is mentioned in the Austrian-German folksong Prinz Eugen, der edle Ritter as the place where the army of Prince Eugene of Savoy set up camp before the Siege of Belgrade (1717) that liberated the city from the Ottoman Empire.

History

[edit]

The area of Zemun has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. Baden culture graves and ceramics like bowls and anthropomorphic urns were found in the town.[4] Bosut culture graves were found in nearby Asfaltna Baza.[5] The first Celtic settlements in Taurunum area originate from the 3rd century BC when the Scordisci occupied several Thracian and Dacian areas of the Danube. The Scordisci founded both Taurunum and Singidunum across the Sava, predecessor of modern Belgrade.[6] The Romans came in the 1st century BC, Taurunum became part of the Roman province of Pannonia around 15 AD. It had a fortress[7] and served as a harbour for the Pannonian (Roman) fleet of Singidunum (Belgrade).[8] The pen of Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) was said to be found in Taurunum.[9] After the Great Migrations the area was under the authority of various peoples and states, including the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of the Gepids and the Bulgarian Empire. The town was conquered by the Kingdom of Hungary in the 12th century and in the 15th century it was given as a personal possession to the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. After the nearby Serbian Despotate fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1459, Zemun became an important military outpost. In 1521, the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary, 500 šajkaši (river flotilla troops) led by Croatian Marko Skoblić, and Serbs[10] fought against the invading Ottoman army of Suleyman the Magnificent. Despite hard resistance, Zemun fell on July 12[11] and Belgrade soon afterwards.[12][better source needed] In 1541, Zemun was integrated into the Syrmia sanjak of the Budin pashaluk.

Zemun and the southeastern Syrmia were conquered by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1717, after the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Peterwardein (5 August 1716) and through the Treaty of Požarevac (German: Passarowitz) became a property of the Schönborn family. In 1736, Zemun was the site of a peasant revolt. Its strategic location near the confluence of the Sava and the Danube placed it in the center of the continued border wars between the Habsburg and the Ottoman empires. The Treaty of Belgrade of 1739 finally fixed the border, the Military Frontier was organized in the region in 1746, and the town of Zemun was granted the rights of a military commune in 1749. In 1754, the population of Zemun included 1,900 Eastern Orthodox Christians, 600 Catholics, 76 Jews, and about 100 Romani. In 1777, the population of Zemun numbered 1,130 houses with 6,800 residents, half of which were ethnic Serbs, while another half of population was composed of Catholics, Jews, Armenians and Muslims. Among Catholic population, the largest ethnic group were Germans. From this period originates the increased settlement of Germans and Hungarians in the Zemun.

While during the Ottoman period Zemun was a typical oriental-type small town, with khans, mosques and large number of Turkish population, after becoming part of Austria, the town prospered as an important road intersection and a border city, which boosted trade.[13] The town had a port on the Danube and was a major fishing center. It is recorded that in 1793, a 700 kg (1,500 lb) heavy Beluga sturgeon was caught.[14] In 1816 it was greatly expanded by mass resettlement of Germans and Serbs in the new town suburbs of Franzenstal and Gornja Varoš, respectively. In the 19th century, Zemun reached 7,089 residents and 1,310 houses. Zemun also became important in Serbian history as the refuge for Karađorđe in 1813 as well as many other people from the nearby Belgrade and the rest of Karađorđe's Serbia which fell to the Ottoman rule.

During the Revolution of 1848–1849, Zemun was one of the de facto capitals of Serbian Vojvodina, a Serbian autonomous region within Habsburg Empire, but in 1849, it was returned under the administration of the Military Frontier. With the abolishment of the Military Frontier in 1881, Zemun and the rest of the eastern Srem was included into Syrmia County of Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, part of Austria-Hungary. The first railway line that connected it to the west was built in 1883, and the first railway bridge over the Sava followed shortly thereafter in 1884.

The Zemun Fortress was the site of the first shots fired during World War I, when the Austro-Hungarian Army shelled the Serbian capital of Belgrade. Serbian engineers responded by demolishing the Old Railway Bridge over the Sava River, damaging an Austro-Hungarian Navy patrol boat below. During the Serbian campaign at the beginning of World War I, Zemun was briefly occupied by the Royal Serbian Army, and many South Slavs living in the city fled to Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian Balkan Army under Oskar Potiorek quickly retook the city and hanged suspected collaborators.[15] The city returned to Serbian control on November 5, 1918. The town became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Kingdom of Yugoslavia). The inter-war period was marked by political struggle between the city gentry (organized into the Radical Party, Democratic Party and the Croatian Peasant Party) and the more socialist parties supported by the ethnic Germans.

In 1934 two intra-city bus lines were introduced connecting Zemun with the parts of Belgrade, and the general shift of attention towards this issue was supported by the growing Serbian population of Zemun.

The Zemun airbases originally built in 1927 were an important geostrategic objective in the Axis invasion of April 1941. Following the surrender of Yugoslavia that same month, Zemun, along with the rest of Syrmia, was given to the Independent State of Croatia. The city was taken from Axis control in 1944, and since then, it is part of Serbian region known as Central Serbia. The city is now home of the Air force command building, a monumental edifice, situated at 12 Аvijatičarski Square in Zemun, Belgrade.

Geography

[edit]

The Municipality has an area of 153 square kilometres (59 square miles). It is located in the eastern Syrmia region, in the central-western section of the Belgrade City area. The urban section of Zemun is both the most northern and the most western section of urban Belgrade. Zemun borders the province of Vojvodina to the west (municipality of Stara Pazova and municipality of Pećinci), and municipalities of Surčin to the south, Novi Beograd to the south-east and Palilula and Stari Grad across the Danube.

The core of the city are the neighborhoods of Donji Grad, Gardoš, Ćukovac and Gornji Grad. To the south, Zemun continues into Novi Beograd with which it makes one continuous urban area (neighborhood of Tošin Bunar). In the west it extends into the neighborhoods of Altina and Plavi Horizonti and to the north-west into Galenika, Zemun Polje and further into Batajnica.

Zemun originally developed on three hills, Gardoš, Ćukovac and Kalvarija, on the right bank of the Danube, where the widening of the Danube begins and the Great War Island is formed at the mouth of the Sava river. Actually, these hills are not natural features. Zemun loess plateau is the former southern shelf of the ancient, now dried, Pannonian Sea. Modern area of Zemun's Donji Grad was regularly flooded by the Danube and the water would carve canals through the loess. Citizens would then build pathways along those canals and so created the passages, carving the hills out of the plateau. After massive 1876 floods, local authorities began the construction of the stony levee along the Danube's bank. Levee, a kilometer long, was finished in 1889. Today it appears that Zemun is built on several hills, with passages between them turned into modern streets, but the hills are actually manmade.[16]

The Danube bank in the north is mostly marshy, so the settlements are built further from the river (Batajnica) separated from it by hillocks (up to 114 metres (374 ft)). The city of Zemun itself was built right on the bank, 100 metres (330 ft) above sea level. These are points of the Zemun loess plateau, an extension of the Syrmia loess plateau, which continues into the crescent-shaped Bežanijska Kosa loess hill on the south-east. The yellow loess is thick up to 40 meters and very fertile, with rich, grass-improved, humus chernozem. The uninhabited river islands of Great War Island and Little War Island on the Danube, also belong to the municipality Zemun, too.

Loess cliff "Zemun" was protected by the city on 29 November 2013. It consists of the very steep right bank of the Danube and is a typical example of the dry land loess. There are four distinguished loess horizons and four horizons of the fossil earth. The horizons developed during the warmer intervals of the glacials.[17] Loess cliff is estimated to be 500,000 years old. The vertical cliff is 30 to 40 m (98 to 131 ft) high, it is exposed and barren, and the protected area covers 72 ares (78,000 sq ft). It was described for the first time in 1920 by Vladimir Laskarev. Another exposed section of the same loess ridge, Kapela ridge in Batajnica, has also been protected as a separate natural monument. Kapela is older though, originating from some 800,000 years ago.[18]

In September 2018, Belgrade's mayor Zoran Radojičić announced that the construction of a dam on the Danube, in the Zemun-New Belgrade area, will start soon. The dam should protect the city during the high water levels.[19][20] Such project was never mentioned before, nor it was clear how and where it will be constructed, or if it's feasible at all. Radojičić clarified after a while that he was referring to the temporary, mobile flood wall. The wall will be 50 cm (20 in) high and 5 km (3.1 mi) long, stretching from the Branko's Bridge across the Sava and the neighborhood of Ušće in New Belgrade, to the Radecki restaurant on the Danube's bank in the Zemun's Gardoš neighborhood. In case of emergency, the panels will be placed on the existing construction. The construction is scheduled to start in 2019 and to finish in 2020.[21]

Lagums

[edit]

One of the characteristics of the Zemun's topography are the lagums, artificial underground corridors which crisscross below the loess area of Gardoš, Muhar, Ćukovac and Kalvarija. This terrain is one of the most active landslide areas in Belgrade. Being cut into for centuries, the loess in some sections have cliffs vertical up to 90%. The Romans began digging the lagums at least as early as 1,700 years ago,[22] using them mostly as the food storages, but later were also used for supply and eventual hiding and evacuation. In the previous centuries, settlers left many vertical shafts which ventilated the lagums, drying the loess and keeping it compact.

The loess is useful for this: it is strong, durable, and easy to be dug through. However, it turns into sand when mixed with water. The average temperature in the lagums is 16 °C (61 °F)[23]

Though used by the local population as food storages, during the Ottoman period, the Turkish administration did not commonly use them. After the Austrians acquired Zemun, they used the underground to store ammunition. In this period, the myths of the entire grid of underground corridors connecting Zemun and Belgrade under the Sava river originated. However, historians dispute this as, though the Austrians held Zemun permanently from 1717, they held Belgrade only from 1717 to 1739, which was not enough for such a major engineering enterprise, given the technology of the period. On 31 July 1938, a section of the Zemun's Roman Catholic cemetery collapsed and fell through into the lagum on which it was built, one of the largest in Zemun. As of this time people tended to label any old structures as "Roman", believing that the Romans had built them, they referred to the corridors as the "Roman" ones.[23]

After World War II, as the city rapidly urbanized, the new settlers were unaware of the lagums, especially the largest one, which covered an area of 450 m2 (4,800 sq ft) on Ćukovac. As there was no sufficient sewage system at that time, they built septic tanks and collected rainwater, but also as the ventilation shafts in time were covered or filled with garbage, it all made the ground wet in the course of several decades. The lagums retained the moist and began to collapse. Eventually, the walls and houses became unstable to the point of breaking façades and walls. In 1988 city authorities finally intervened as the houses began to sink in three streets. Holes were drilled to connect the surface with the largest lagum. Altogether, 22 drillings were made and 779 m3 (27,500 cu ft) of concrete were poured into the lagum, filling it until the ground was stabilized, but the lagum was destroyed in the process. Still, the situation is critical after almost every downpour. On 29 September 2011, while constructing the supporting wall which was to prevent landslide in the section of Kalvarija, the construction workers triggered one which killed four of them. A 225 m (738 ft) long lagum, which was explored by 2001, is located right below the place where the tragedy happened. So far, 76 long corridors have been discovered, with many smaller ones. The longest of them is 96 metres (315 ft) long and the total explored length is 1,925 m (6,316 ft). They cover an area of 4,882 m2 (52,550 sq ft). Many have collapsed during time, as they are not being kept since the 1980s.[24][25][26][27]

Still, it is believed that the majority of them haven't been discovered or explored. The walls of those which have, are being covered with bricks or woods. Some corridors are dead ends while others are connected. The "Galeb" rowing club uses one of the lagums on the bank of the Danube to store their kayaks.[23]

There are numerous stories about the Zemun's lagums, their distribution and expansion of the grid. The tales of lagums connecting Zemun with the bank of the Danube, neighboring Bežanija, the Roman well in the Belgrade Fortress and the other parts of Belgrade across the Sava, became a commonplace in Zemun's and Belgrade's urban mythology. Older myths even included various monsters dwelling below. Still, there is a historically confirmed story of the house of Živojin Vukojčić, Interbellum industrialist. His son, Dragi Vukojčić, built the underground rooms in 1943 as a shelter, but the local myths claimed that he had an entire factory below. Still, when the agents from the Communist security agency OZNA came to arrest him after the war, Vukojčić asked to let him change his clothes. He fled down the lagum to the Danube, and then via boat and a plane, escaped to Brazil. Latest stories include criminals from the Zemun Clan, who were allegedly hiding in the lagums during the police Operation Sabre, after they assassinated prime minister Zoran Đinđić on 12 March 2003. In the 21st century, the stories of mythical creatures are replaced with those of criminals, smugglers, drug addicts and homeless people.[23]

The lagums remained an important part of the local Zemun identity, preserving the spirit of the town and personal memories. For generations of the local boys, descending into the lagums, wandered through them and stayed below as long as possible, which was of a coming of age ritual. Even the name, Zemun, comes from the words zemlja (earth) or zemunica (dug out).[23]

Neighbourhoods and suburbs

[edit]

The municipality has only two official settlements: Belgrade (Zemun), which is part of the urban Belgrade city proper (uža teritorija grada; statistically classified as Belgrade-part) and the village of Ugrinovci (which includes the hamlets of Grmovac and Busije). Many of the neighbourhoods developed in the last few decades (Altina, Plavi Horizonti, Kamendin, Grmovac, Busije, etc.).

There are four local communities in the municipality: Batajnica, Ugrinovci, Zemun Polje and Nova Galenika. They were formed in 2009 after the old ones were abolished in 1996.[28][29]

Urban:

Suburban:

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 18,528 | — |

| 1931 | 28,074 | +4.24% |

| 1948 | 40,428 | +2.17% |

| 1953 | 49,361 | +4.07% |

| 1961 | 72,896 | +4.99% |

| 1971 | 109,619 | +4.16% |

| 1981 | 135,313 | +2.13% |

| 1991 | 141,952 | +0.48% |

| 2002 | 145,632 | +0.23% |

| 2011 | 157,363 | +0.86% |

| 2022 | 166,049 | +0.49% |

| Source: [3] | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 42,197 | — |

| 1953 | 51,089 | +3.90% |

| 1961 | 74,791 | +4.88% |

| 1971 | 111,877 | +4.11% |

| 1981 | 138,591 | +2.16% |

| 1991 | 146,056 | +0.53% |

| 2002 | 152,831 | +0.41% |

| 2011 | 168,170 | +1.07% |

| 2022 | 177,908 | +0.51% |

| Source: [3] | ||

As Zemun grew into one of the most populous neighborhoods of Belgrade, population of the municipality had a steady growth since World War II. According to the 2022 census, the urban population of Zemun was 166,049, while the municipality had 177,908 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

[edit]The ethnic structure of the municipality, according to 2022 census:[30]

| Ethnic group | Population | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 150,113 | 84.38% |

| Romani | 4,884 | 2.75% |

| Yugoslavs | 1,018 | 0.57% |

| Croats | 749 | 0.42% |

| Montenegrins | 398 | 0.22% |

| Muslims | 385 | 0.22% |

| Macedonians | 312 | 0.18% |

| Russians | 304 | 0.17% |

| Gorani | 301 | 0.17% |

| Hungarians | 172 | 0.1% |

| Bosniaks | 133 | 0.07% |

| Slovenians | 126 | 0.07% |

| Slovaks | 124 | 0.07% |

| Albanians | 109 | 0.06% |

| Bulgarians | 62 | 0.03% |

| Ukrainians | 54 | 0,03% |

| Germans | 49 | 0.03% |

| Romanians | 49 | 0.03% |

| Others | 1,676 | 0.94% |

| Undeclared/Unknown | 16,890 | 9.49% |

| Total | 177,908 |

Administration

[edit]

The municipality of Zemun became part of the Belgrade City Area (Teritorija grada Beograda) with the division of Yugoslavia into banovinas by king Alexander I on October 3, 1929. On April 1, 1934, the municipality itself was absorbed into the municipality of Belgrade, so the post of the president of the municipality of Zemun was abolished and "Zemun section administrator" was appointed to the Belgrade's city government.

Between 1941 and 1944 it was occupied by the German army as part of the East Syrmia Occupation Zone (Okupationsgebiet Ostsyrmien). Germany technically recognised Zemun and surroundings as part of the Independent State of Croatia puppet regime, but Zemun remained under direct German rule. During this time the Sajmište concentration camp was established, where over 20000 Jews, Romani and opponents of the Nazi regime died.

After 1945 Zemun was administratively divided into the City of Zemun and Zemun district (srez), unlike rest of Belgrade which was divided into raions. In 1955 both City of Zemun and most of the Zemun district were incorporated into Belgrade again. In the 1950s and 1960s, municipalities of Boljevci and Dobanovci were annexed to the municipality of Surčin while Batajnica was annexed to Zemun itself. In 1965 Surčin was annexed to the municipality of Zemun which marked the largest territorial expansion of Zemun (438 km2). However, on November 24, 2003, Belgrade City assembly voted to re-create the municipality of Surčin, but it remained under the administration of Zemun until November 3, 2004, when separate municipal government was established after the local elections. A motion for Batajnica to split from Zemun too was active for a while in the early 2000s (see List of former and proposed municipalities of Belgrade).

Presidents of the municipality:

- October 3, 1929 – June 20, 1930: Petar S. Marković

- June 20, 1930 – December 8, 1931: Svetislav Popović

- December 9, 1931 – March 31, 1934: Miloš Đorić

Administrator of the Zemun section:

- 1934 – April 12, 1941: Nikola Folger

German mayors:

- April 13, 1941 – July 1941: Johannes Moser (d. 1980)

- July 1941 – December 1941: Stefan Seifert

- December 1941 – October 1944: Johannes Moser (d. 1980)

Partisan military administrator:

- October 22, 1944 – October 26, 1944: Milan Žeželj (1917–1995)

Presidents of the municipal assembly:

- October 26, 1944 – July 8, 1945: Ljubomir Milovanović

- July 8, 1945 – 1947: Dimitrije Anokić

- 1947–1949: Milenko Jovanović

- 1949–1950: Božidar Tomić (b. 1914)

- 1950: Lazar Popov (acting)

- 1950–1955: Stojan Svilarić (b. 1920)

- 1955–1958: Branko Pešić (1922–1986)

- 1958–1962: Aleksandar S. Jovanović

- 1962–1967: Čedomir Jovićević

- 1967–1971: Svetozar Papić

- 1971–1973: Radojko Filipović

- 1973–1974: Pavle Ilić (acting)

- 1974–1978: Branko S. Radivojević (b. 1932)

- 1978–1982: Ilija Kragović

- 1982–1986: Novak Rodić

- 1986–1989: Petar Stolica

- 1989: Dobrivoje Perović

- 1989–1992: Živko Davidović (b. 1935)

- 1992 – December 1996: Nenad Ribar

- December 1996 – April 1998: Vojislav Šešelj (b. 1954)

- April 1998 – October 17, 2000: Stevo Dragišić (b. 1971)

- October 17, 2000 – November 4, 2004: Vladan Janićijević (b. 1934)

Presidents of the municipality:

- November 4, 2004 – June 4, 2008: Gordana Pop-Lazić (b. 1956)

- June 4, 2008 – March 5, 2009: Slavko Jerković (b. 1959)

- March 5, 2009 – July 23, 2009: Zdravko Stanković (acting)

- July 23, 2009 – July 4, 2013: Branislav Prostran (b. 1976)

- July 4, 2013 – September 10, 2020: Dejan Matić (b. 1969)

- September 10, 2020 – present: Goran Kovačević (b. 1969)

Economy

[edit]Zemun is one of the most developed municipalities of Belgrade, with developed industries in almost every branch. Zemun has two large and still growing industrial zones, one located along the highway and the other one along the road to Batajnica and further to Novi Sad (Galenika, Goveđi Brod, etc.). Industries include: heavy agricultural machines and appliances (Zmaj), precise and optical instruments and automatized appliances (Teleoptik), clocks (INSA), busses and other heavy vehicles (Ikarbus), pharmaceuticals (Galenika), plastics (Grmeč), shoes (Obuća Beograd), textile (TIZ, Zekstra), food, candies and chocolate (Soko Štark), metals (IMPA, Intersilver), wood and furniture (Gaj, Reprek), recycling (INOS metali and INOS papir), beverages (Coca-Cola, Navip), chemicals (Roma), building materials (DIA), electronics, leather, etc. In addition to this dozens of halls, and warehouses are built throughout both industrial zones.

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[31]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 201 |

| Mining and quarrying | 13 |

| Manufacturing | 10,018 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 471 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 424 |

| Construction | 3,815 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 15,487 |

| Transportation and storage | 5,141 |

| Accommodation and food services | 2,419 |

| Information and communication | 1,600 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 483 |

| Real estate activities | 246 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 3,758 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 5,444 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 989 |

| Education | 4,731 |

| Human health and social work activities | 4,632 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1,147 |

| Other service activities | 1,060 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 88 |

| Total | 62,198 |

Transportation

[edit]

Railways in Zemun municipality | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Road

[edit]Several important roads of Serbia run through the municipality. The Belgrade-Zagreb highway, the old (Batajnički drum) and new (highway) road Belgrade-Novi Sad, the still in construction starting point (Batajnica-Dobanovci) of the future Belgrade beltway (Batajnica-Bubanj Potok), Belgrade-Novi Sad railway, etc. Until 2014, Zemun had no bridges, apart from the seasonal pontoon bridge which connects the mainland with the Great War Island during summer. The first bridge over the Danube, Pupin Bridge which connected Zemun to Borča, was completed in 2014.

In March 2016, mayor of Belgrade Siniša Mali announced the massive reconstruction of the Old Sava Bridge.[32][33] However, in May 2017, after the project papers were publicized, it was obvious that the city actually wanted to demolish the bridge completely and build a new one. Citizens protested while the experts rejected the reasons named by the authorities, adding that it is a mere money throwing on the unnecessary project.[32][34] Mali said that the old bridge will not be demolished but moved, and that citizens will decide where, but he gave an idea to move it to Zemun, as the permanent pedestrian bridge to the Great War Island. In an article "Cloud over the Great War Island", Aleksandar Milenković, member of the Academy of Architecture of Serbia, opposed the motion. He expressed fear that having in mind the "synchronous ad hoc decisions of the administration", the reaction should be prompt as the seemingly benign idea is actually a strategically disastrous enterprise (concerning the protected wildlife on the island). He also suspects that the administration in this case, just as in all previous ones, will neglect the numerous theoretical and empirical guidelines.[35]

River

[edit]In 2014 the government set the locality of the former port as the future revitalized port area.[36] In April 2018 it was announced that the pier for the touristic ships and cruisers will be built on the quay, constructed near the Old Port Authority (Stara Kapetanija) where the old Zemun port was located. It is designed to accept ships up to 120 m (390 ft) long and 15 m (49 ft) wide.[37] It is the second international touristic pier in Belgrade, after the one in Savamala, on the Sava river.[38] Construction ultimately began in June 2019 and the slabs from the previous embankment were discovered so as several submerged vessels.[39] The pier was finished on 6 June 2020.[40]

Railway

[edit]Gradual moving of trains from the Belgrade Main railway station to the new, Prokop station began in the early 2016. In December 2017, all but two national trains were dislocated to "Belgrade Center".[41] In the scopes of dislocation, a new, central Belgrade freight station is planned in Zemun. But, the problems arose immediately. The Prokop is still not finished, has no station building and a proper access road and public transportation connections with the rest of the city. Additionally, it has no facilities for loading and unloading cars from the auto trains nor was ever planned top have one and this facility is to be a part of the Zemun freight station. Still, in January 2018 it was announced that the Main station will be completely closed for traffic on 1 July 2018, even though none of the projects needed for a complete dislocation of the railway traffic are finished. The Prokop is incomplete, a projected main freight station in Zemun is not being adapted at all while there is even no project on a Belgrade railway beltway.[42]

A series of temporary solutions will have to be applied. One is a defunct and deteriorated Topčider station, which will be revitalized and adapted for auto trains, until the Zemun station becomes operational. Freight station in Zemun will be located between the already existing stations Zemun and Zemun Polje, on the area of 35 ha (86 acres). Revitalization of the existing 6 km (3.7 mi) of tracks and 14,500 m2 (156,000 sq ft) of buildings will be followed by the construction of the 17 km (11 mi) of new tracks and additional 18,800 m2 (202,000 sq ft) of edifices. Deadline is also 2 years, but the works will start at the end of 2018. This means that the planned Belgrade railway junction won't be finished before 2021, at best. However, minister for transportation, Zorana Mihajlović, in December 2017 gave conflicting deadlines. For the Zemun station, she said that it should be finished by the end of 2018, even though, as of January 2018, non of the works have started.[42]

Aerial

[edit]Batajnica Airbase with a limited civil traffic is also located in the municipality, near the Batajnica settlement.

In 1928, building company "Šumadija" proposed the construction of the cable car, which they called "air tram". The project was planned to connect Zemun to Kalemegdan on Belgrade Fortress, via Great War Island. The interval of the cabins was set at 2 minutes and the entire route was supposed to last 5 minutes. The project was never realized.[43]

Panoramic views

[edit]Architecture, culture and education

[edit]

White Bear Tavern is a former kafana in the neighborhood of Ćukovac. First mentioned in 1658, it is the oldest surviving edifice on the urban territory of modern Belgrade, not counting the Belgrade Fortress.[44] However, Zemun developed completely independently from Belgrade for centuries and for the most part during the history two towns belonged to two different states. Zemun became part of the same administrative unit as Belgrade on 4 October 1929,[45] lost a separate town status to Belgrade in 1934[46] and made a continuous built-up area with Belgrade only since the 1950s. Hence, the House at 10 Cara Dušana Street in Belgrade's downtown neighborhood of Dorćol is usually named as the oldest house in Belgrade,[47][48] while the White Bear Tavern is titled as the oldest house in Zemun.[49]

The first professional theatre in Zemun was established on 22 October 1969 in the Main Street (Maršala Tita at the time), as an offshoot of the National Theatre in Belgrade.[50] Madlenianum Opera and Theatre was founded in 1997 as the first private opera in this part of Europe. The founder and the donor of Madlenianum is Madlena Zepter. Madlenianum has been organized as a model of a new musical-scenic theatre, without its permanent ensemble, but with a permanent organization and administration apparatus and a technical team. [51]

The faculty of agriculture of the Belgrade University is located in Zemun, as well as many other important higher schools (Internal affairs, Economics, Technics and machines, Medicine, Zemun gymnasium) and institutes (Institute for agriculture and forestry, Institute for mining, world-famous Institute for corn in Zemun Polje, Institute for livestock, Institute for the implementation of the nuclear energy in agriculture, Institute for physics).

Zemun has a town museum, located in the historic Spirta House.[52][53]

Two of Belgrade's major hospitals-clinical centers are located in Zemun: KBC Zemun and KBC Bežanijska Kosa, as is the retirement home Bežanijska Kosa, the largest one in Belgrade. Churches include the Gardoš cemetery church and the Hariš chapel, Saint Nicholas, Saint Archangel Gabriel and two Roman Catholic churches.

Zemun is known for many squares, though almost all of them are small in size: Magistratski, Senjski, Veliki, Branka Radičevića, Karađorđev, Masarikov, etc. On one of them, the Zemun open green market is located. The bank of the Danube is turned into Zemunski Kej, a kilometers long promenade, with various entertainment facilities along it, including barges-cafés, amusement park and especially formerly largest hotel in Belgrade, Hotel Jugoslavija.

The remnants of the old town which existed during battles between Kingdom of Hungary and Byzantine Empire in the 12th century are known as Zemunski Grad (Zemun Town).[citation needed] Today visible ruins however are of the medieval fortress (angular towers and parts of the defending wall) of the 1521 Ottoman siege. The Kula Sibinjanin Janka (The tower of Janos Hunyadi) or the Millennium tower was built and officially opened on August 20, 1896, to celebrate a thousand years of Hungarian settlement in the Pannonian plain. The tower was built as a combination of various styles, mostly influenced by the Roman elements. Being a natural lookout, it was used by Zemun's firemen for decades. Today, the tower is better known after the Janos Hunyadi, who actually died in the old fortress four and a half centuries before the tower was built. In general, Gardoš is today the most recognizable symbol of Zemun. For the most part, the neighborhood preserved its old looks, with narrow, still mostly cobblestoned streets unsuitable for modern vehicles, and individual residential houses.[citation needed]

There are five official parks in Zemun, though there are much more green areas in general. The largest and the oldest is the City park (Gradski park, opened in 1886). There are also the Kej Oslobođenja park (on the quay, renovated in November 2007), Kalvarija, Jelovac and Army park.[54][55] There are also five official forests: three along the highway (Autoput Forest, Belgrade-Zagreb Highway Forests and Nacional Forest), which cover 54.18 hectares (133.9 acres), Bežanijska Kosa Forest, also along the highway (26.06 hectares (64.4 acres)), and Great and Little War Islands (1.9 square kilometres (0.73 sq mi)).[56]

Sport

[edit]The most popular football club in Zemun is FK Zemun, which plays currently in the Serbian First League, the second tier of Serbian football league system, and Teleoptik Zemun, which plays currently in the Serbian League Belgrade. Teleoptik is nowadays generally considered Partizan Belgrade's farm team, with many of Partizan's youth players playing there to gain experience before being promoted to the first team. The municipality has several smaller stadiums, including those of FK Zemun, the Zemun Stadium. One of Belgrade's major sports halls, the Pinki Hall, which is Named after Boško Palkovljević Pinki, is also located in Zemun.

International relations

[edit]Twin towns — Sister cities

[edit]Notable residents

[edit]- Judah Alkalai

- Dejan Čurović

- Ivan Dudić

- Aleksandar Karakašević

- Saša Kovačević

- Mladen Lazarević

- Ljubomir Magaš

- Goran Milošević

- Zoran Modli

- Vladica Popović

- Jovan Prokopljević

- Ivan Pudar

- Radovan Radaković

- Slavko Radovanović

- Boštjan Trilar

- Đorđe Simić

- Darko Tresnjak

See also

[edit]- Monastery of St. Archangel Gabriel, Zemun

- Subdivisions of Belgrade

- List of Belgrade neighbourhoods and suburbs

References

[edit]- ^ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Насеља општине Земун" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Comparative overview of the number of population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011 – Data by settlements, page 29. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4.

- ^ "[Projekat Rastko] Dragoslav Srejovic: Kulture bakarnog i ranog bronzanog doba na tlu Srbije". www.rastko.rs. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Nikola Tasic (January 2004). "Historical picture of development of Early Iron Age in the Serbian Danube basin". Balcanica (35): 7–22. doi:10.2298/BALC0535007T.

- ^ Ana Vuković (8 November 2018). "Tragom Skordiska u našem gradu" [Trails of the Scordisci in our city]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ A manual of ancient and modern history ... William Cooke Taylor, Caleb Sprague Henry

- ^ Vespasian-Barbara Levick

- ^ Biographia classica: the lives and characters of the Greek and Roman classics, by Edward Harwood.

- ^ Rudolf Horvat (1924). "Ban Ivan Karlović". Povijest Hrvatske I. (od najstarijeg doba do g. 1657.). OCLC 560148302.

- ^ Vlatko Rukavina (May 29, 2009). "Hrvatska strana Zemuna". Hrvatska revija (in Croatian). Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ^ See sr:Пад Београда (1521) – Fall of Belgrade (1521) (in Serbian)

- ^ Grozda Pejčić, ed. (2006). Угоститељско туристичка школа – некад и сад 1938–2006. Draslar Partner. p. 65.

- ^ Miroslav Stefanović (22 April 2018). "Мегдани аласа и риба грдосија" [Fights between the fishermen and the giant fishes]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1073 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- ^ Hastings, Max (2013). Catastrophe 1914 : Europe goes to war. New York. ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2. OCLC 828893101.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Miloje Jovanović Miki (2 December 2010). "Brdo Gardoš nije brdo" (in Serbian). Politika. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Vladimir Vukasović (9 June 2013), "Prestonica dobija još devet prirodnih dobara", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (15 May 2022). Милиони година сачувани у стенама главног града [Millions of years preserved in the rocks of the capital city]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ^ J.D. (18 September 2018). "Gradiće se brana na Dunavu!" [A dam will be built on the Danube]. Večernje Novosti (in Serbian).

- ^ Tanjug (17 September 2018). "Uskoro gradnja brane na Dunavu kod Novog Beograda" [Soon building of the dam on the Danube at New Belgrade]. Blic (in Serbian).

- ^ Dejan Aleksić (22 September 2018). "Umesto džakova, mobilna brana protiv poplava" [Mobile dam against the flood, instead of sandbags]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Nikola Bilić (30 October 2011), "Putovanje kroz istoriju beogradskim metroom", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ a b c d e Aleksandra Mijalković (19 August 2018). Призори из земунског подземља [Scenes from the Zemun's underground]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1090 (in Serbian). pp. 24–25.

- ^ "Vumi's Antika – Prikazati pojedinačan prilog – Istorija Gradova-Beograd". www.vumidet.net. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Nikola Belić (8 November 2011), "Klizišta nisu samo hir prirode", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Nikola Belić (22 February 2012), "Otapanje pokreće i klizišta", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (9 October 2011), "Zemun ispod Zemuna", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ "DECISION ON LOCAL COMMUNITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CITY MUNICIPALITY OF ZEMUN" (PDF). 1 April 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Zemun ponovo dobio mesne zajednice". Blic. 18 October 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ ETHNICITY – Data by municipalities and cities (PDF). Belgrade, Serbia: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2023. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9788661612282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-11-22. Retrieved 2023-11-23.

- ^ "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b Dejan Aleksić, Daliborka Mučibabić (18 May 2017). "Stari savski most pada u vodu" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 1 & 16.

- ^ Dijana Radisavljević (17 March 2016). "Rekonstrukcija Savskog mosta 2017 godine" (in Serbian). Blic.

- ^ Adam Santovac (16 May 2017). "Peticija da se ne ruši Stari savski most" (in Serbian). N1. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Dr Aleksandar Milenković (26 July 2017), "Oblak nad Velikim ratnim ostrvom", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (28 December 2019). Утицај пристаништа на животну средину [Effect of the port on the environment]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ Beta agency (24 April 2018). "Turistički kruzeri od sledeće sezone pristaju u Zemun" [Touristic cruisers will stop at Zemun from the next season]. Večernje Novosti (in Serbian).

- ^ Ana Vuković (26 April 2018). "Крузери ће пристајати у Земуну" [Cruisers will stop in Zemun]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (18 November 2019). "Niče pristan u Zemunu" [Pier in Zemun rising]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Julijana Simić Tenšić (7 June 2020). Земун добио међународни пристан [Zemun got international pier]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Serbia, RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of. "Прокоп од данас главна железничка станица". rts.rs. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Dejan Aleksić (16 January 2018). "Posle 134 godine bez vozova u Savskom amfiteatru" [No more trains in Sava amphitheater after 134 years]. Politika (in Serbian). pp. 01 & 16.

- ^ Dejan Spalović (27 August 2012), "San o žičari od Bloka 44 do Košutnjaka", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (14 April 2012), "Kuća na Ćukovcu od 354 leta", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Službene novine KJ br. 232/29 (Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, No. 232/29) (in Serbian). 1929.

- ^ Miodrag A. Dabižić. Prilog prošlosti gradskog parka u Zemunu od sedamdesetih godina XIX veka do 1914. godine (A contribution to the past history of the town park in Zemun from the 1870s to 1914) (in Serbian and English).

- ^ "Cultural monument – House at 10, Cara Dušana Street". Catalogue of the cultural properties in Belgrade.

- ^ Milan Janković (24 May 2010), "Tajna kuće u Dušanovoj 10", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- ^ B.Cvejić (16 October 2016), "Najstarija kuća u Zemunu", Danas (in Serbian)

- ^ Земун добио професионално позориште [Zemun got a professional theatre]. Politika (reprint on 23 October 2019) (in Serbian). 23 October 1969.

- ^ "Monografije Opere i teatra Madlenianum | Opera & Theatre Madlenianum".

- ^ Linkmedia. "Zavičajni muzej Zemuna | Muzeji i galerije | Šta videti". Tourist Organization of Belgrade (in Serbian). Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ "Завичајни музеј Земуна". www.mgb.org.rs. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ "Зоран Алимпић обишао обновљени парк на Мажуранићевом тргу". Град Београд – Званична интернет презентација – Зоран Алимпић обишао обновљени парк на Мажуранићевом тргу. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (24 May 2019). "Парк фест" у најстаријој зеленој оази у Земуну ["Park fest" in the oldest green oasis in Zemun]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 17.

- ^ Anica Teofilović, Vesna Isajlović, Milica Grozdanić (2010). Пројекат "Зелена регулатива Београда" – IV фаза: План генералне регулације система зелених површина Београда (концепт плана) [Project "Green regulations of Belgrade" – IV phase: Plan of the general regulation of the green area system in Belgrade (concept of the plan)] (PDF). Urbanistički zavod Beograda. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Zemun – Beograd". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2007. Stalna konferencija gradova i opština. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Puteaux – Qu'est-ce que le jumelage?". Mairie de Puteaux [Puteaux Official Website] (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-11-26. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mala Enciklopedija Prosveta, Third edition (1985); Prosveta; ISBN 86-07-00001-2

- Jovan Đ. Marković (1990): Enciklopedijski geografski leksikon Jugoslavije; Svjetlost-Sarajevo; ISBN 86-01-02651-6

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Zemun

- Gardoš Zemun 360 Virtual tour

- Osnovna škola Gornja Varoš Zemun