Young Macedonian Literary Society

The Young Macedonian Literary Society,[1] also known as Young Macedonian Literary Association, was founded in 1891 in Sofia, Bulgaria. The association was formed as primarily a cultural and educational society. It published a magazine called Loza (The Vine).

Background

[edit]Following the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870, as a result of plebiscites held between 1872 and 1875, the Slavic population in the bishoprics of Skopje and Ohrid voted overwhelmingly in favor of joining the new national Church (Skopje by 91%, Ohrid by 97%).[2] At that time a long discussion was held in the Bulgarian periodicals about the need for a dialectal group (Eastern Bulgarian, Western Macedonian or compromise) upon which to base the new standard and which dialect that should be.[3] During the 1870s this issue became contentious and sparked fierce debates.[4]

After a distinct Bulgarian state was established in 1878, Macedonia remained outside its borders. In the 1880s, the Bulgarian codificators rejected the idea of a Macedono-Bulgarian linguistic compromise and chose eastern Bulgarian dialects as a basis for standard Bulgarian. One purpose of the Young Macedonian Literary Society magazine was to defend the Macedonian dialects, and to have them more represented in the Bulgarian language. Their articles were of a historical, cultural, and ethnographic nature.

Foundation and ideology

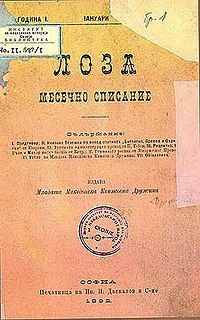

[edit]The organization was established in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1891 as a type of cultural and educational society by Macedonian emigrants.[5] It had the purpose of protecting the various Macedonian dialects.[6] In 1892, it created and published a monthly magazine called Loza (The Vine), which is where their name "Lozari" (Lozars) was derived from.[5] The first issue of the magazine was printed in Sofia in January 1892 and its main article contained the Program Principles of the organization. The association's founders included Kosta Shahov, its chairman.[7]

In the middle of 1892, Bulgarian prime minister Stefan Stambolov's government officially banned the organization.[5] In May 1894, after the fall of Stambolov, the Macedonian Youth Society in Sofia revived the Young Macedonian Literary Society. The new group had a newspaper called Glas Makedonski and opened a Reading Room Club.[8] The group included a number of educators, revolutionaries, and public figures from Macedonia—Evtim Sprostranov, Petar Poparsov, Thoma Karayovov, Hristo Popkotsev, Dimitar Mirchev, Andrey Lyapchev, Naum Tyufekchiev, Georgi Balaschev, Georgi Belev, etc.[9]

Later, for a short time, Dame Gruev, Gotse Delchev, Luka Dzherov, Ivan Hadzhinikolov and Hristo Matov were also involved in the company.[10] These activists went on various paths. Some members went on to become leaders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization in 1894 and the Supreme Macedonian Committee in 1895. Others later became prominent intellectuals, including Andrey Lyapchev who became the Prime Minister of Bulgaria.

The Greek national activist from Aromanian background Konstantinos Bellios was considered a "Macedonian compatriot" by the Lozars.[11] The members of the Young Macedonian Literary Association self-identified as Macedonian Bulgarians.[12][13]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Its magazine Loza was attacked in the Bulgarian press as "separatist."[7] An article in the official People's Liberal Party newspaper "Svoboda" blamed the organization for lack of loyalty and separatism. The Society rejected these accusations of linguistic and national separatism,[14] and in a response to "Svoboda" claimed that their "society is far from any separatist thoughts, in which we were accused and to say that the ideal of Young Macedonian Literary Society is not separatism, but unity of the entire Bulgarian nation".[15] Some scholars identify the journal as an early platform of Macedonian linguistic separatism.[16][17] Macedonian historians, such as Andrew Rossos, saw expression of Macedonian nationalism in their activity.[18] However, the Lozars demonstrated both: Bulgarian and Macedonian loyalty and combined their Bulgarian nationalism with Macedonian regional and cultural identity.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Kempgen, Sebastian; Kosta, Peter; Berger, Tilman; Gutschmidt, Karl, eds. (2014). Die slavischen Sprachen / The Slavic Languages. Halbband 2. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1472. ISBN 9783110215472.

- ^ The Politics of Terror: The Macеdonian Liberation Movements, 1893–1903, Duncan M. Perry, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, p. 15.

- ^ "Венедиктов Г. К. Болгарский литературный язык эпохи Возрождения. Проблемы нормализации и выбора диалектной основы. Отв. ред. Л. Н. Смирнов. М.: "Наука"" (PDF). 1990. pp. 163–170. (Rus.). Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ^ Ц. Билярски, Из българския възрожденски печат от 70-те години на XIX в. за македонския въпрос, сп. "Македонски преглед", г. XXIII, София, 2009, кн. 4, с. 103–120.

- ^ a b c Lajosi, Krisztina; Stynen, Andreas, eds. (2020). The Matica and Beyond: Cultural Associations and Nationalism in Europe. BRILL. pp. 151–155. ISBN 9789004425385.

- ^ Denis Š. Ljuljanović (2023). Imagining Macedonia in the Age of Empire: State Policies, Networks and Violence (1878–1912). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 210. ISBN 9783643914460.

- ^ a b Joshua A. Fishman (2011). The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: "The First Congress" Phenomenon. Walter de Gruyter. p. 162. ISBN 9783110848984.

- ^ Mercia MacDermott (1978). Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotsé Delchev. Journeyman Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780904526325.

- ^ "100 years IMORO", prof. Dimitŭr Minchev, prof. Dimitŭr Gotsev, Macedonian scientific institute, 1994, Sofia, p. 37; (Bg.)

- ^ History of the Sofia University "St. Kliment Okhridski", Georgi Naumov, Dimitŭr Tsanev, University publishing house "St. Kliment Okhridski", 1988, p. 164; (Bg.)

- ^ The Young Macedonian Literary Association (1892). "Preamble". Loza. Vol. 1. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "Though Loza adhered to the Bulgarian position on the issue of the Macedonian Slavs' ethnicity, it also favored revising the Bulgarian orthography by bringing it closer to the dialects spoken in Macedonia." Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 241.

- ^ "The Young Macedonian Literary Association's Journal, Loza, was also categorical about the Bulgarian character of Macedonia: "A mere comparison of those ethnographic features which characterize the Macedonians (we understand: Macedonian Bulgarians), with those which characterize the free Bulgarians, their juxtaposition with those principles for nationality which we have formulated above, is enough to prove and to convince everybody that the nationality of the Macedonians cannot be anything except Bulgarian." Freedom or Death, The Life of Gotsé Delchev, Mercia MacDermott, The Journeyman Press, London & West Nyack, 1978, p. 86.

- ^ "Loza", Issue 1, pp. 91-96

- ^ "Loza", Issue 1, p. 58: Just a comparison of those ethnographic features that characterize the Macedonians (we understand the "Macedonian Bulgarians") with those that characterize the free Bulgarians, their arrangement to those principles of nationality, which we listed above, is enough to show us and convince It is clear that the ethnicity of the Macedonians cannot be other than "Bulgarian". And the identity of these features has long been established and confirmed by selfless science: only the blind and enemies of the Bulgarian future cannot see the all-encompassing unity that fully prevails between the population from Drin River to the Black Sea and from the Danube to the Aegean Sea... If we indifferently and with broken hands stand and watch only how day by day the cultural, moral and material ties between Macedonia and Bulgaria become stronger and stronger; as the young Macedonians under the guidance of Bulgarian teachers become accustomed to be proud of the great deeds of the Bulgarian history and to think of renewing the Bulgarian glory and power, Macedonia will soon become part of the Bulgarian nation and state...

- ^ "Macedonian Language and Nationalism During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries", Victor Friedman, p. 286.

- ^ Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans, Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson, p. 145.

- ^ Rossos, Andrew (2008). Macedonia and the Macedonians, Stanford University: Hoover Institution Press, ISBN 9780817948832, p. 96.

- ^ "Macedonian historiography often refers to the group of young activists who founded in Sofia an association called the ‘Young Macedonian Literary Society’. In 1892, the latter began publishing the review Loza [The Vine], which promoted certain characteristics of Macedonian dialects. At the same time, the activists, called "Lozars" after the name of their review, "purified" the Bulgarian orthography from some rudiments of the Church Slavonic and brought it closer to Vuk Karadžić's Serbian phonetic script. They expressed likewise a kind of Macedonian patriotism attested already by the first issue of the review: its materials greatly emphasized identification with Macedonia as a genuine ‘fatherland’. (...) In any case, it is hardly surprising that the Lozars demonstrated both Bulgarian and Macedonian loyalty: what is more interesting is namely the fact that their Bulgarian nationalism was somehow harmonized with a Macedonian self-identification that was not only a political one but also demonstrated certain ‘cultural’ contents." We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, pp. 120-121.