Xiang Yu

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2013) |

| Xiang Yu 項羽 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

As depicted in the album Portraits of Famous Men, c. 1900, housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art | |||||

| Ruler of Chu | |||||

| Reign | 206–202 BC | ||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Yi of Chu | ||||

| Born | 232 BC Xiaxiang (下相) (modern Suqian, Jiangsu) | ||||

| Died | 202 BC (aged 29–30) He County, Anhui | ||||

| Wife | Consort Yu | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Xiang Chao | ||||

| Xiang Yu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 項羽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 项羽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hegemon-King of Western Chu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 西楚霸王 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

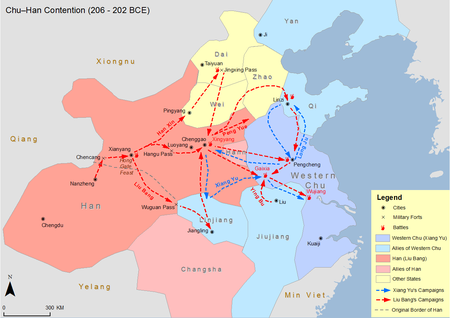

Xiang Yu (c. 232– c.January 202 BC),[1] born Xiang Ji, was the Hegemon-King of Western Chu during the Chu–Han Contention period (206–202 BC) of China. A noble of the state of Chu, Xiang Yu rebelled against the Qin dynasty, destroying their last remnants and becoming a powerful warlord. He was granted the title of "Duke of Lu" (魯公) by King Huai II of the restoring Chu state in 208 BC. The following year, he led the Chu forces to victory at the Battle of Julu against the Qin armies led by Zhang Han. After the fall of Qin, Xiang Yu was enthroned as the "Hegemon-King of Western Chu" (西楚霸王) and ruled a vast area spanning central and eastern China, with Pengcheng as his capital. He engaged Liu Bang, the founding emperor of the Han dynasty, in a long struggle for power, known as the Chu–Han Contention, which concluded with his eventual defeat at the Battle of Gaixia and his suicide.

Names and titles

[edit]Xiang Yu's family name was Xiang (項) while his given name was Ji (籍) and his courtesy name was Yu (羽; Yǔ; Yü; Jyu5). He is best known as Xiang Yu.

Xiang Yu is popularly known as the "Hegemon-King of Western Chu" (西楚霸王; Xīchǔ bà wáng). This title is sometimes shortened to "Ba Wang". Since Xiang Yu's death, the term "Ba Wang" has come to refer specifically to Xiang.

Family background

[edit]There are two accounts of Xiang Yu's family background. The first claimed that Xiang Yu was from the house of Mi (羋), the royal family of the Chu state in the Zhou dynasty. His ancestors were granted the land of Xiang (項) by the king of Chu and had since adopted "Xiang" as their family name. The other account claimed that Xiang Yu was a descendant of a noble clan from the Lu state and his family had served in the Chu military for generations. Xiang Yu's grandfather Xiang Yan was a well known general who led the Chu army in resisting the Qin invaders led by Wang Jian, and was killed in action when Qin conquered Chu in 223 BC.

Xiang Yu was born in 232 BC in the late Warring States period when the Qin state started unifying the other six major states. According to the descendants of the Xiang family in Suqian, Xiang Yu's father was Xiang Chao (項超), Xiang Yan's eldest son. Xiang Yu was raised by his elder uncle Xiang Liang because his father died early. In 221 BC, when Xiang Yu was about 11 years old, the Qin state unified China and established the Qin dynasty.

One of Xiang's eyes had a double pupil[2] just like the mythical Emperor Shun and Duke Wen of Jin. He was thus seen as an extraordinary person because his unique double pupil was a mark of a king or sage in Chinese tradition. Xiang Yu was slightly taller than eight chi, or approximately 1.86 m (6 ft 1 in), and possessed unusual physical strength, as he could lift a ding.[2]

Early life

[edit]In his younger days, Xiang Yu was instructed in scholarly arts and swordsmanship but he did not manage to master what he was taught, and his uncle Xiang Liang was not very satisfied with him.[2] Xiang Yu said, "Books are only useful in helping me remember my name. Mastering swordsmanship allows me to face only one opponent, so it's not worth learning. I want to learn how to defeat thousands of enemies."[2] Hence, his uncle tried to educate him in military strategy and the art of war instead, but Xiang Yu stopped learning after he had grasped the main ideas; Xiang Liang was disappointed with his nephew, who showed no sign of motivation or apparent talent apart from his great strength, so he gave up and let Xiang Yu decide his own future.[2][3]

When Xiang Yu grew older, Xiang Liang killed someone so they fled to Wu to evade the authorities. At that time, Qin Shi Huang was on an inspection tour in that area and Xiang Yu and his uncle watched the emperor's procession pass by. Xiang Yu said, "I can replace him."[2] Xiang Liang was shocked and immediately covered his nephew's mouth with his hand. Afterwards, Xiang Liang began to see his nephew in a different light.

Revolt against the Qin

[edit]

In 209 BC, during the reign of Qin Er Shi, peasant rebellions erupted throughout China to overthrow the Qin dynasty, plunging China into a state of anarchy. Yin Tong (殷通), the administrator of Kuaiji, wanted to start a rebellion as well, so he invited his uncle Xiang Liang to meet him and discuss their plans. The pair lured Yin Tong into a trap and killed him instead, with Xiang Yu personally striking down hundreds of Yin's men. Xiang Liang initiated the rebellion himself and rallied about 8,000 men to support him. Xiang Liang proclaimed himself Administrator of Kuaiji while appointing Xiang Yu as a general. Xiang Liang's revolution force grew in size until it was between 60,000 and 70,000. In 208 BC, Xiang Liang installed Mi Xin as King Huai II of Chu to rally support from those eager to help him overthrow the Qin dynasty and restore the former Chu state. Xiang Yu distinguished himself as a competent marshal and mighty warrior on the battlefield while participating in the battles against Qin forces.

Later that year, Xiang Liang was killed at the Battle of Dingtao against the Qin army led by Zhang Han and the military power of Chu fell into the hands of the king and some other generals. In the winter of 208, another rebel force claiming to restore the Zhao state, led by Zhao Xie (趙歇), was besieged in Handan by Zhang Han. Zhao Xie requested for reinforcements from Chu. King Huai II granted Xiang Yu the title of "Duke of Lu" (魯公), and appointed him as a second-in-command to Song Yi, who was ordered to lead an army to reinforce Zhao Xie. At the same time, the king placed Liu Bang in command of another army to attack Guanzhong, the heartland (capital territory) of Qin. The king promised that whoever managed to enter Guanzhong first will be granted the title "King of Guanzhong".

Battle of Julu

[edit]The Chu army led by Song Yi and Xiang Yu reached Anyang, some distance away from Julu (巨鹿; modern Xingtai, Hebei), where Zhao Xie's forces had retreated to. Song Yi ordered the troops to lay camp there for 46 days and he refused to accept Xiang Yu's suggestion to proceed further. Xiang Yu took Song Yi by surprise in a meeting and killed him on a charge of treason. Song Yi's other subordinates were afraid of Xiang Yu so they let him become the acting commander-in-chief. Xiang Yu sent a messenger to inform King Huai II and the king approved Xiang's command.

In 207 BC, Xiang Yu's army advanced towards Julu and he sent Ying Bu and Zhongli Mo to lead the 20,000 strong vanguard army to cross the river and attack the Qin forces led by Zhang Han, while he followed behind with the remaining majority of the troops. After crossing the river, Xiang Yu ordered his men to sink their boats and destroy all but three days worth of rations, in order to force his men to choose between prevailing against overwhelming odds within three days or die trapped before the walls of the city with no supplies or any hope of escape. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Chu forces scored a great victory after nine engagements, defeating the 300,000 strong Qin army. After the battle, other rebel forces, including those not from Chu, came to join Xiang Yu out of admiration for his martial valour. When Xiang Yu received them at the gate, the rebel chiefs were so fearful of him that they sank to their knees and did not even dare to look up at him.

Zhang Han sent his deputy Sima Xin to Xianyang to request for reinforcements and supplies from the Qin imperial court. However, the eunuch Zhao Gao deceived the emperor and the emperor dismissed Zhang Han's request. Zhao Gao even sent assassins to kill Sima Xin when the latter was returning to Zhang Han's camp, but Sima managed to escape alive. In dire straits, Zhang Han and his 200,000 troops eventually surrendered to Xiang Yu in the summer of 207. Xiang Yu perceived the surrendered Qin troops as disloyal and a liability, and had them executed by burying them alive at Xin'an (新安; modern Yima, Henan]). Zhang Han, along with Sima Xin and Dong Yi, were spared from death. Xiang Yu appointed Zhang Han as "King of Yong", while Sima Xin and Dong Yi were respectively conferred the titles of "King of Sai" and "King of Di".

Feast at Hong Gate

[edit]After his victory at the Battle of Julu, Xiang Yu prepared for an invasion on Guanzhong, the heartland of the Qin dynasty. In the winter of 207 BC, Ziying of Qin surrendered to Liu Bang in the Qin capital of Xianyang, bringing an end to the Qin dynasty. When Xiang Yu arrived at Hangu Pass, the eastern gateway to Guanzhong, he saw that the pass was occupied by Liu Bang's troops, a sign that Guanzhong was already under Liu's control. Cao Wushang (曹無傷), a subordinate of Liu Bang, sent a messenger to see Xiang Yu, saying that Liu would become King of Guanzhong in accordance with King Huai II's earlier promise, while Ziying would be appointed as Liu's chancellor. Xiang Yu was furious after hearing that. At that time, he had about 400,000 troops under his command while Liu Bang only had a quarter of that number.

As strongly encouraged by his advisor Fan Zeng, Xiang Yu invited Liu Bang to attend a feast at Hong Gate and plotted to kill Liu during the banquet. However, Xiang Yu later listened to his uncle Xiang Bo and decided to spare Liu Bang. Liu Bang escaped during the banquet under the pretext of going to the latrine.

Xiang Yu paid no attention to Liu Bang's presumptive title and led his troops into Xianyang in 206. He ordered the execution of Ziying and his family, as well as the destruction of the Epang Palace by fire. It was said that Xiang Yu would leave behind a trail of destruction in the places he passed by, and the people of Guanzhong were greatly disappointed with him.[4]

Despite advice from his subjects to remain in Guanzhong and continue with his conquests, Xiang Yu was insistent on returning to his homeland in Chu. He said, "To not return home when one has made his fortune is equivalent to walking on the streets at night in glamorous outfits. Who would notice that?"[2] One of his followers said, "It is indeed true when people say that the men of Chu are apes dressed in human clothing." Xiang Yu had that man boiled alive when he heard that insult.[2]

Division of the empire

[edit]After the downfall of the Qin, Xiang Yu offered Huai II the more honourable title of "Emperor Yi of Chu" and announced his decision to divide the former Qin empire. Xiang Yu declared himself "Hegemon-King of Western Chu" (西楚霸王) and ruled nine commanderies in the former Liang and Chu territories, with his capital at Pengcheng. In the spring of 206, Xiang Yu divided the former Qin Empire into the Eighteen Kingdoms, to be granted to his subordinates and some leaders of the former rebel forces. He moved some of the rulers of other states to more remote areas and granted the land of Guanzhong to the three surrendered Qin generals, ignoring Emperor Yi's earlier promise to appoint Liu Bang as king of that region. Liu Bang was relocated to the remote Hanzhong area and given the title of "King of Han" (漢王).

Xiang Yu appointed several generals from the rebel coalition as vassal kings, even though these generals were subordinates of other lords, who should rightfully be the kings in place of their followers. Xiang Yu also left out some other important rebel leaders who did not support him earlier, but did contribute to the overthrow of Qin. In winter, Xiang Yu moved Emperor Yi to the remote region of Chen, effectively sending the puppet emperor into exile. At the same time, he issued a secret order to the vassal kings in that area and had the emperor assassinated during his journey in 205. The emperor's death was later used by Liu Bang as political propaganda to justify his war against Xiang Yu.

Shortly after the death of Emperor Yi, Xiang Yu had King Hann Cheng put to death and seized Han's lands for himself. Several months later, chancellor Tian Rong of Qi took control over the Three Qis (Jiaodong, Qi and Jibei) from their respective kings and reinstated Tian Fu as the King of Qi, but he took over the throne himself afterwards. Similarly, Chen Yu, a former vice chancellor of Zhao, led an uprising against the King of Changshan, Zhang Er, and seized Zhang's domain and reinstalled Zhao Xie as the King of Zhao.

Chu–Han Contention

[edit]

Battle of Pengcheng

[edit]In 206, Liu Bang led his forces to attack Guanzhong. At that time, Xiang Yu was at war with Qi and did not focus on resisting the Han forces. The following year, Liu Bang formed an alliance with another five kingdoms and attacked Western Chu with a 560,000 strong army, capturing Xiang Yu's capital of Pengcheng. Upon hearing this, Xiang Yu led 30,000 men to attack Liu Bang and defeated the latter at the Battle of Pengcheng, with the Han army suffering heavy casualties.

Battle of Xingyang

[edit]Liu Bang managed to escape after his defeat with Xiang Yu's troops in pursuit. Han troops retreated to Xingyang and defended the city firmly, preventing Chu forces from advancing west any further, but only managed to hold on until 204 BC. Liu Bang's subordinate Ji Xin disguised himself as his lord and surrendered to Xiang Yu, buying time for Liu Bang to escape. When Xiang Yu learned that he had been fooled, he became furious and had Ji Xin burned to death. After the fall of Xingyang, Chu and Han forces were divided on two fronts along present-day Henan. However, Xiang Yu's forces were not faring well on the battlefront north of the Yellow River, as the Han army led by Han Xin defeated his troops in every single battle. At the same time, Liu Bang's ally Peng Yue led his men to harass Xiang Yu's rear.

Treaty of Hong Canal

[edit]By 203, the tide had turned in favour of Han. Xiang Yu managed to capture Liu Bang's father after a year-long siege and he threatened to boil Liu's father alive if Liu refused to surrender. Liu Bang remarked that he and Xiang Yu were oath brothers,[5] so if Xiang killed Liu's father, he would be guilty of patricide. Xiang Yu requested for an armistice, known as the Treaty of Hong Canal, and returned the hostages he had captured to Liu Bang as part of their agreement. The treaty divided China into east and west under the Chu and Han domains respectively.

Battle of Guling

[edit]Shortly after, as Xiang Yu was retreating eastwards, Liu Bang renounced the treaty and led his forces to attack Western Chu. Liu Bang sent messengers to Han Xin and Peng Yue, requesting for their assistance in forming a three-pronged attack on Xiang Yu, but Han Xin and Peng Yue did not mobilise their troops and Liu Bang was defeated by Xiang Yu at the Battle of Guling. Liu Bang retreated and reinforced his defences, while sending emissaries to Han Xin and Peng Yue, promising to grant them fiefs and titles of vassal kings if they would join him in attacking Western Chu.

Defeat and death

[edit]

In 202, Han armies led by Liu Bang, Han Xin, and Peng Yue attacked Western Chu from three sides and trapped Xiang Yu's army, which was low on supplies, at Gaixia. Liu Bang ordered his troops to sing folk songs from the Chu region to create a false impression that Xiang Yu's native land had been conquered by Han forces. The morale of the Chu army plummeted and many of Xiang Yu's troops deserted in despair. Xiang Yu sank into a state of depression and he composed the Song of Gaixia. His wife Consort Yu committed suicide. The next morning, Xiang Yu led about 800 of his remaining elite cavalry on a desperate attempt to break out of the encirclement, with 5,000 enemy troops pursuing them.

After crossing the Huai River, Xiang Yu was only left with a few hundred soldiers. They were lost in Yinling (陰陵) and Xiang Yu asked for directions from a farmer, who directed him wrongly to a swamp. When Xiang Yu reached Dongcheng (東城), only 28 men were left, with the Han troops still following him. Xiang Yu made a speech to his men, saying that his downfall was due to Heaven's will and not his personal failure. After that, he led a charge out of the encirclement, killing one Han general in the battle. Xiang Yu then split his men into three groups to confuse the enemy and induce them to split up as well to attack the three groups. Xiang Yu took the Han troops by surprise again and slew another enemy commander, inflicting about 100 casualties on the enemy, while he only lost two men.

Xiang Yu retreated to the bank of the Wu River (near modern He County, Maanshan, Anhui) and the ferryman at the ford prepared a boat for him to cross the river, strongly encouraging him to do so because Xiang Yu still had the support of the people from his homeland in the south. Xiang Yu said that he was too ashamed to return home and face his people because none of the first 8,000 men from Jiangdong who followed him on his conquests survived. He refused to cross and ordered his remaining men to dismount, asking the ferryman to take his warhorse Zhui (騅), back home.

Xiang Yu and his men made a last stand against wave after wave of Han forces until only Xiang himself was left alive. Xiang Yu continued to fight on and slew over 100 enemy soldiers, but he had also sustained several wounds all over his body. Just then, Xiang Yu saw an old friend Lü Matong among the Han soldiers, and he said to Lü, "I heard that the King of Han (Liu Bang) has placed a price of 1,000 gold and the title of "Wanhu Marquis" (萬戶侯; lit. "marquis of 10,000 households") on my head. Take it then, on account of our friendship." Xiang Yu then committed suicide by slitting his throat with his sword, and a brawl broke out among the Han soldiers at the scene due to the reward offered by Liu Bang, and Xiang Yu's body was said to be dismembered and mutilated in the fight. The reward was eventually claimed by Lü Matong and four others.

After Xiang Yu's death, Western Chu surrendered and China was united under Liu Bang's rule, marking the victory of the Han dynasty. Liu Bang held a grand state funeral for Xiang Yu in Gucheng (穀城; in Dongping County, Tai'an, Shandong), with the ceremony befitting Xiang's title "Duke of Lu". Xiang Yu's relatives were spared from death, including Xiang Bo, who saved Liu Bang's life at Hong Gate, and they were granted marquis titles.[6]

Evaluation

[edit]Classical

[edit]Xiang Yu's biography in the Records of the Grand Historian describes him as someone who boasted about his achievements and thought highly of himself. Xiang Yu preferred to depend on his personal abilities as opposed to learning with humility from others before him. Sima Qian thought that Xiang Yu had failed to see his own shortcomings and to make attempts to correct his mistakes, even until his death. Sima Qian thought that it was ridiculous when Xiang Yu claimed that his downfall was due to Heaven's will and not his personal failure.[2] Xiang Yu depicted as a ruthless leader, ordering the massacres of entire cities even after they surrendered peacefully. This often led to cities putting up strong resistance, as they knew they would be killed even if they surrendered. The most notorious example of his cruelty was when he ordered the 200,000 surrendered Qin troops to be buried alive after the Battle of Julu,[7][verification needed][8][verification needed] and the gruesome methods of execution he employed against his enemies and critics. In contrast, Liu Bang is portrayed as a shrewd and cunning ruler who could be brutal at times,[4] but forbade his troops from looting the cities they captured and spared the lives of the citizens, earning their support and trust in return. Xiang Yu's story became an example for Confucianists to advocate the idea that leaders should rule with benevolence and not govern by instilling fear in the people. His ambitions ended with the collapse of Western Chu, his defeat by Liu Bang, and his death at the early age of around 30.

Liu Bang's general Han Xin, who was one of Xiang Yu's opponents on the battlefield, made a statement criticising Xiang, "A man who turns into a fierce warrior when he encounters a rival stronger than he is, but also one who is sympathetic and soft hearted when he sees someone weaker than he is. Neither was he able to make good use of capable generals nor was he able to support Emperor Yi of Chu, as he killed the emperor. Even though he had the name of a Conqueror, he had already lost the favour of the people."[9][verification needed]

The Tang dynasty poet Du Mu mentioned Xiang Yu in one of his poems Ti Wujiang Ting (題烏江亭): "Victory or defeat is common in battle. One who can endure humiliation is a true man. There are several talents in Jiangdong, who knows if he (Xiang Yu) can make a comeback?"[10][verification needed] The Song dynasty poet Wang Anshi had a different opinion, writing that "the warrior is already tired after so many battles. His defeat in the Central Plains is hard to reverse. Although there are talents in Jiangdong, are they willing to help him?"[11][verification needed] The Song dynasty female poet Li Qingzhao wrote: "A hero in life, a king of ghosts after death. Until now we still remember Xiang Yu, who refused to return to Jiangdong."[12][verification needed]

Xiang Yu is popularly viewed as a leader who possessed great courage but lacked wisdom, and his character is aptly summarised using the Chinese idiom 有勇無謀; 有勇无谋; yǒu yǒng wú móu,[13] meaning "has courage but lacks tactics", "foolhardy". Xiang Yu's battle tactics were studied by later military leaders while his political blunders served as cautionary tales for later rulers.[citation needed] Another Chinese idiom 四面楚歌; sì miàn chǔ gē; 'surrounded by Chu songs', was also derived from the Battle of Gaixia, and used to describe someone in a desperate situation without help. Another saying by Liu Bang, "Having a Fan Zeng but unable to use him" (有一范增而不能用), was also used to describe Xiang Yu's reliance on his advisor Fan Zeng and failure to actually listen to Fan's advice.[citation needed]

Modern era

[edit]Modern study of history has drawn similarities between Xiang Yu's military brilliance and that of his Mediterranean contemporary Hannibal.[14] Researchers emphasized Xiang Yu's strategic thinking, while also exploiting any opportunities to launch a surprise attack in the morning under the cover of darkness, as Xiang Yu was outstanding in this regard. His tactical early morning raids on the enemy fully demonstrated his superb strategy of mobilization and artistic prowess, despite facing unprecedented crises.[14]

Mao Zedong also once mentioned Xiang Yu, "We should use our remaining strength to defeat the enemy, instead of thinking about achieving fame like the Conqueror."[15][verification needed] In 1964, Mao also pointed out three reasons for Xiang Yu's downfall: not following Fan Zeng's advice to kill Liu Bang at Hong Gate, and letting Liu leave; adhering firmly to the terms of the peace treaty without considering that Liu Bang might betray his trust; building his capital at Pengcheng.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]

Song of Gaixia

[edit]The "Song of Gaixia" (垓下歌) was a song composed by Xiang Yu while he was trapped by Liu Bang's forces at Gaixia.[2]

The lyrics in English as follows are Burton Watson's translation:[16]

《垓下歌》 |

- ^ "Dapple" is Watson's translation of the name of Xiang Yu's warhorse Zhui (騅)

Xiang Yu's might and prowess in battle has been glorified in Chinese folk tales, poetry, and novels, and he has been the subject of films, television, plays, Chinese operas, video games and comics. His classic image is that of a heroic and brave, but arrogant and bloodthirsty warrior-king. His romance with his wife Consort Yu and his suicide have also added a touch of a tragic hero to his character.[17]

Poetry, folk tales, novels

[edit]Xiang Yu's might and prowess in battle appears in Chinese folk tales and poetry, such as at Gaixia.[18] The Meng Qiu (蒙求), an 8th-century Chinese primer by the scholar Li Han, contains the four-character rhyming couplet "Ji Xin impersonates the Emperor". It referred to the episode in the Battle of Xingyang when Ji Xin and 2,000 women disguised themselves as Liu Bang and his army, to distract Xiang Yu in order to buy time for Liu Bang to escape from the city of Xingyang.[19]

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, Sun Ce is nicknamed "Little Conqueror" (小霸王)[20] and is compared favourably to Xiang Yu by a contemporary.[20] This comparison was actually made in historical fact.[21] Sun Ce is best known for his conquests in the Jiangdong region that laid the foundation of the state of Eastern Wu in the Three Kingdoms era. In Water Margin, another of the Four Great Classical Novels, Zhou Tong, one of the 108 outlaws, is nicknamed "Little Conqueror" for his resemblance to Xiang Yu in appearance.

In Jin Ping Mei, (Ci Hua edition) Xiang Yu is mentioned as an example of a tragic character in the song at the opening of the first chapter.[22]

The character Mata Zyndu in Ken Liu's epic fantasy novel The Grace of Kings is based on Xiang Yu.

Operas

[edit]A famous Beijing opera, The Hegemon-King Bids His Lady Farewell, depicts the events of Xiang Yu's defeat at the Battle of Gaixia. The title of the play was borrowed as the Chinese title for Chen Kaige's award-winning motion picture Farewell My Concubine.[23]

Television and film

[edit]- Portrayed by Shek Sau in the 1985 Hong Kong television series The Battlefield.

- Portrayed by Ray Lui in the 1994 Hong Kong film The Great Conqueror's Concubine.

- Portrayed by Hu Jun in the 2003 Chinese television series The Story of Han Dynasty.

- Portrayed by Kwong Wah in the 2004 Hong Kong television series The Conqueror's Story.

- Portrayed by Tan Kai in the 2010 Chinese television series The Myth.

- Portrayed by Feng Shaofeng in the 2011 Chinese film White Vengeance.

- Portrayed by Peter Ho in the 2012 Chinese television series King's War.

- Portrayed by Ming Dao in the 2012 Chinese television series Beauties of the Emperor.

- Portrayed by Daniel Wu in the 2012 Chinese film The Last Supper.

- Portrayed by Qin Junjie in the 2015 Chinese television series The Legend of Qin.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ 12th month of the 5th year of Liu Bang's reign (including his tenure as King of Han), per vol.11 of Zizhi Tongjian. The month correpsonds to 29 Dec 203 BC to 27 Jan 202 BC in the proleptic Julian calendar.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1739) [90s BCE]. "7: 項羽本紀". Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian] (in Literary Chinese) (punctuated ed.). Beijing: Imperial Household Department.

- ^ "Xiang Yu - Famous Leader of Uprising in Ancient China". Cultural China. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ a b Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1739) [90s BCE]. "Vol. 8: 高祖本紀". Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian] (in Literary Chinese) (punctuated ed.). Beijing: Imperial Household Department.

- ^ Liu Bang and Xiang Yu became sworn brothers in a ceremony with King Huai II of Chu as their witness in 208.

- ^ Ming Hung, Hing (2011). The Road to the Throne: How Liu Bang Founded China's Han Dynasty. Algora Publishing. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-87586-838-7.

- ^ 王杰. 项羽坑杀了二十万秦朝降兵吗? (in Chinese).[permanent dead link]

- ^ “火烧阿房”:蒙的什么冤,平的什么反? (in Chinese). 陕西新闻网. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ (遇強則霸的匹夫之勇,和遇弱則憐的婦人之仁。既不能任用賢能將帥,又曾遷逐楚義帝,用兵趕盡殺絕。雖名為霸王,其實民心盡失。)

- ^ (勝敗兵家事不期,包羞忍恥是男兒。江東弟子多才俊,捲土重來未可知。)

- ^ (百戰疲勞壯士衰,中原一敗勢難回。江東子弟今雖在,肯與君王捲土來。)

- ^ (生當作人傑,死亦為鬼雄,至今思項羽,不肯過江東。)

- ^ 看《神话》穿越历史 西楚霸王项羽有勇无谋 (in Chinese). 半岛网. 27 January 2010. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011.[verification needed]

- ^ a b Zhang, Zhe; Osiki, Omon (2011). "A comparative study of Xiang Yu and hannibal's strategic thinking with that of Shaka the Zulu of South Africa". African Nebula (4). Samar Habib. doi:10.2307/523668. JSTOR 523668. S2CID 145190863.

- ^ (宜將剩勇追窮寇,不可沽名學霸王。)

- ^ Watson, Burton (2000). "The Hegemon's Lament". In Minford, John; Lau, Joseph S.M. (eds.). An Anthology of Translations Classical Chinese Literature Volume I: From Antiquity To The Tang Dynasty. Columbia University Press. pp. 414–415. ISBN 0-231-09676-3.

- ^ Lau, Miriam Leung Che (2015). "Effects of Chinese opera on the reproductions of Ibsen's plays". Nordlit. 34: 315–326 [317–318]. doi:10.7557/13.3376.

- ^ "Xiang Yu (Chinese rebel leader)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2008 [1998].

- ^ Johnson, David (December 1985). "The City-God Cults of T'ang and Sung China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 45 (2): 363–457. doi:10.2307/2718969. JSTOR 2718969.

- ^ a b Luo Guanzhong (1998) [1300s]. Sanguo Yanyi 三國演義 [Romance of the Three Kingdoms] (in Chinese). Yonghe: Zhiyang Publishing House. 15: 太史慈酣鬥小霸王 孫伯符大戰嚴白虎, p. 98; 29: 小霸王怒斬于吉 碧眼兒坐領江東, p. 187.

- ^ Yu Pu (虞溥) [in Chinese] (300). Jiangbiao zhuan 江表傳. Cited in Chen Shou (1977) [429]. "46: 孫破虜討逆傳". In Pei Songzhi (ed.). Annotated Records of the Three Kingdoms 三國志注 (in Chinese). Taipei: Dingwen Printing. p. 1111 n. 2.

- ^ "Text of Jin Ping Mei". Chinese Text Project. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Yu, Jingyuan (June 2024). "Nationalism and Identity Crisis: Analyzing "Farewell to My Concubine" Through Historical Contexts" (PDF). Arts Culture and Language. 1 (7). Dean & Francis: 4. doi:10.61173/b7360d62.

Sources

[edit]- Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1739) [90s BCE]. "Vol. 7". Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian] (in Literary Chinese) (punctuated ed.). Beijing: Imperial Household Department.

- Ban Gu; Ban Zhao; Ban Biao (1962) [111]. "31: 項籍傳". Book of Han 漢書. Zhonghua Shuju.

- Sima Guang, ed. (1934) [1084]. Zizhi Tongjian. Hong Kong: Zhonghua Shuju. vols. 8, 9, 10, 11.