Xenophobia and discrimination in Turkey

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In Turkey, xenophobia and discrimination are present in its society and throughout its history, including ethnic discrimination, religious discrimination and institutional racism against non-Muslim and non-Sunni minorities.[9] This appears mainly in the form of negative attitudes and actions by some people towards people who are not considered ethnically Turkish, notably Kurds, Armenians, Arabs, Assyrians, Greeks, Jews,[10] and peripatetic groups like Romani people,[11] Domari, Abdals[12] and Lom.[13]

In recent years, racism in Turkey has increased towards Middle Eastern nationals such as Syrian refugees, Afghan, Pakistani, and African migrants.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

There is also reported rising resentment towards the influx of Russians, Ukrainians and maybe Belarusians in the country as a result of the Ukrainian war from Turks whom claim it is creating a housing crisis for locals.[20][21][22][23]

Overview

[edit]| Year | 1914 | 1927 | 1945 | 1965 | 1990 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | 12,941 | 13,290 | 18,511 | 31,139 | 56,860 | 71,997 |

| Greeks | 1,549 | 110 | 104 | 76 | 8 | 3 |

| Armenians | 3,604 | 77 | 60 | 64 | 67 | 50 |

| Jews | 128 | 82 | 77 | 38 | 29 | 27 |

| Others | 176 | 71 | 38 | 74 | 50 | 45 |

| Total | 15,997 | 13,630 | 18,790 | 31,391 | 57,005 | 72,120 |

| % non-Muslim | 19.1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Racism and discrimination in Turkey can be traced back to the Ottoman Empire. In the 1860s, some Ottoman Turkish intellectuals such as Ali Suavi stated that:[25]

- Turks are superior to other races in political, military and cultural aspects

- The Turkish language surpasses the European languages in its richness and excellence

- Turks constructed the Islamic civilization.

In the 1920s and 1930s racism became an influential aspect in Turkish politics which counted with the support of the Turkish Government.[26] Through the Turkish History Thesis and the Sun Language Theory, a Turkish racial superiority was to be scientifically proven. The Turkish History Thesis claimed a Turkish racial origin of the modern European people, while the Sun Language Theory called the Turks as having been the first people to have spoken, therefore being Turkish the origin of all other languages.[26] Congresses to promote those ideas to the western scholar world were organized in Turkey.[27] The State Employee Law enacted in 1926 aimed at the Turkification of work life in Turkey.[28][29] This law defined Turkishness as a condition which was necessary for a person who wished to become a state employee.[28] As in 1932 Keriman Halis Ece was elected Miss Universe, the Turkish President Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) was pleased with the fact that an international jury found a woman representing the essence of the Turkish race the one.[30] Early racists in Turkey were Nihal Atsız and Reha Oğuz Türkkan, who both competed by applying the correct way in defining Turkishness.[31][32] The two were charged in the Racism–Turanism Trial in 1944 together with other 21 defendants which included Zeki Velidi Togan and Alparslan Türkeş. Several defendants were sentenced to jail terms, but after a retrial in October 1945 they were all acquitted.[33] The Turkish idealist movement is influenced by Adolf Hitler's views of racism. His book Mein Kampf (Turkish: Kavgam), is very popular amongst right-wing politicians, and as Bülent Ecevit wanted to ban its sale in Turkey, they prevented it.[34]

In Turkey in 2002 the Ministry of Education adopted an educational curriculum with respect to the Armenians which was widely condemned as racist and chauvinistic.[35] The curriculum contained textbooks which included phrases such as "we crushed the Greeks" and "traitor to the nation."[35] Thereafter, civic organizations, including the Turkish Academy of Sciences, published a study which deplored all racism and sexism in textbooks.[35] However, a report which was published by the Minority Rights Group International (MRG) in 2015 states that the curriculum in schools continues to depict "Armenians and Greeks as the enemies of the country."[36] Nurcan Kaya, one of the authors of the report, concluded: "The entire education system is based on Turkishness. Non-Turkish groups are either not referred to or referred in a negative way."[37]

As of 2008 Turkey has also seen an increase in "hate crimes" which are motivated by racism, nationalism, and intolerance.[38] According to Ayhan Sefer Üstün, the head of the parliamentary Human Rights Investigation Commission, "Hate speech is on the rise in Turkey, so new deterrents should be introduced to stem the increase in such crimes".[39] Despite provisions in the Constitution and the laws there have been no convictions for a hate crime so far, for either racism or discrimination.[38] In Turkey since the beginning of 2006, a number of killings have been committed against people who are members of ethnic and religious minority groups, people who have a different sexual orientation and people who profess a different social/sexual identity. Article 216 of the Turkish Penal Code imposes a general ban against publicly inciting people's hatred and disgust.[38]

According to an article which was written in 2009 by Yavuz Baydar, a senior columnist for the daily newspaper the Zaman, racism and hate speech are on the rise in Turkey, particularly against Armenians and Jews.[41] On January 12, 2009, he wrote that "If one goes through the press in Turkey, one would easily find cases of racism and hate speech, particularly in response to the deplorable carnage and suffering in Gaza. These are the cases in which there is no longer a distinction between criticizing and condemning Israel's acts and placing Jews on the firing line."[42] In 2011 Asli Çirakman asserted that there has been an apparent rise in the expression of xenophobic feeling against the Kurdish, Armenian, and Jewish presences in Turkey.[10] Çirakman also noted that the ethno-nationalist discourse of the 2000s identifies the enemies-within as the ethnic and religious groups which reside in Turkey, such as the Kurds, the Armenians, and the Jews.[10]

In 2011, a Pew Global Attitudes and Trends survey of 1,000 Turks found that 6% of them had a favorable opinion of Christians, and 4% of them had a favorable opinion of Jews. Earlier, in 2006, the numbers were 16% and 15%, respectively. The Pew survey also found that 72% of Turks viewed Americans as hostile, and 70% of them viewed Europeans as hostile. When asked to name the world's most violent religion, 45% of Turks cited Christianity and 41% cited Judaism, with 2% saying that it was Islam. Additionally, 65% of Turks said the Westerners were "immoral".[43]

One of the main challenges which is facing Turkey according to the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) is the need to reconcile the strong sense of national identity and the wish to preserve the unity and integrity of the State with the right of different minority groups to express their own senses of ethnic identity within Turkey, for example, the right of a minority group to develop its own sense of ethnic identity through the maintenance of that ethnic identity's linguistic and cultural aspects.[44]

In a recent discovery by the Armenian newspaper Agos, secret racial codes were used to classify minority communities in the country.[45] According to the racial code, which is believed to be established during the foundations of the republic in 1923, Greeks are classified under the number 1, Armenians 2, and Jews 3.[45] Altan Tan, a deputy of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), believed that such codes were always denied by Turkish authorities but stated that "if there is such a thing going on, it is a big disaster. The state illegally profiling its own citizens based on ethnicity and religion, and doing this secretly, is a big catastrophe".[45]

According to research which was conducted by Istanbul Bilgi University, with the support of the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBITAK) between 2015 and 2017, 90 percent of youths said they would not want their daughters to marry someone who was "from the 'other' group." While 80 percent of youths said they would not want to have a neighbor who was from the "other," 84 percent said they would not want their children to be friends with children who were from the "other" group. 84 percent said they would not do business with members of the "other" group. 80 percent said they would not hire anyone who was from the "other." Researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with young people between the ages of 18 and 29. When they were asked to state which groups they most perceived to be the "other," they ranked homosexuals first with 89 percent, atheists and nonbelievers ranked second with 86 percent, people from other faiths ranked third with 82 percent, minorities stood at 75 percent and extremely religious people ranked fifth with 74 percent.[46]

Against Kurds

[edit]Mahmut Esat Bozkurt, a former Minister of Justice claimed in 1930 the superiority of the Turkish race over the Kurdish one, and permitted non-Turks only the right to be servants and slaves.[47]

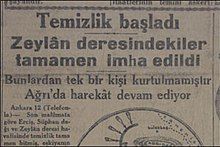

The Zilan massacre of 1930[48][49][50] was a massacre[51][52] of the Kurdish residents of Turkey during the Ararat rebellion in which 800–1500 armed men participated.[citation needed] According to the daily Cumhuriyet dated July 16, 1930, about 15,000 people were killed and Zilan River was filled with dead bodies as far as its mouth.[53][54][55][56] On August 31, 1930, the daily Milliyet published the declaration of the Turkish prime minister İsmet İnönü: "Only the Turkish nation has the right to demand ethnic rights in this country. Any other element does not have such a right.[57][58]" and "They are Eastern Turkish who were deceived by unfounded propaganda and eventually lost their way."[59]

Kurds have had a long history of discrimination and massacres which have been perpetrated against them by the Turkish government.[60] One of the most significant is the Dersim massacre, where according to an official report of the Fourth General Inspectorate, 13,160 civilians were killed by the Turkish Army and 11,818 people were taken into exile, depopulating the province in 1937–38.[61] According to the Dersimi, many tribesmen were shot dead after surrendering, and women and children were locked into haysheds which were then set on fire.[62] David McDowall states that 40,000 people were killed[63] while sources of the Kurdish Diaspora claim over 70,000 casualties.[64]

In an attempt to deny their existence, the Turkish government categorized Kurds as "Mountain Turks" until 1991.[65][66][67] Other than that, various historical Kurdish personalities were tried to be Turkified by claiming that there is no race called Kurdish and that the Kurds do not have a history.[citation needed] Since then, the Kurdish population of Turkey has long sought to have Kurdish included as a language of instruction in public schools as well as a subject. Several attempts at opening Kurdish instruction centers were stopped on technical grounds, such as wrong dimensions of doors. Turkish sources claimed that running Kurdish-language schools was wound up in 2004 because of 'an apparent lack of interest'.[68] Even though Kurdish language schools have started to operate, many of them have been forced to shut down due to over-regulation by the state. Kurdish language institutes have been monitored under strict surveillance and bureaucratic pressure.[69] Using Kurdish language as main education language is illegal in Turkey. It is accepted only as subject courses.

Kurdish is permitted as a subject in universities,[70] some of those are only language courses while others are graduate or post-graduate Kurdish literature and language programs.[71][72]

Due to the large number of Turkish Kurds, successive governments have viewed the expression of a Kurdish identity as a potential threat to Turkish unity, a feeling that has been compounded since the armed rebellion initiated by the PKK in 1984. One of the main accusations of cultural assimilation relates to the state's historic suppression of the Kurdish language. Kurdish publications created throughout the 1960s and 1970s were shut down under various legal pretexts.[73] Following the military coup of 1980, the Kurdish language was officially prohibited in government institutions.[74]

| Party | Year banned |

|---|---|

| People's Labor Party (HEP) | 1993

|

| Freedom and Democracy Party (ÖZDEP) | 1993

|

| Democracy Party (DEP) | 1994

|

| People's Democracy Party (HADEP) | 2003

|

| Democratic Society Party (DTP) | 2009

|

In April 2000, US Congressman Bob Filner spoke of a "cultural genocide", stressing that "a way of life known as Kurdish is disappearing at an alarming rate".[76] Mark Levene suggests that the genocidal practices were not limited to cultural genocide, and that the events of the late 19th century continued until 1990.[60] In 2019, Deutsche Welle reported that Kurds had been increasingly subject to violent hate crimes.[77]

Certain academics have claimed that successive Turkish governments adopted a sustained genocide program against Kurds, aimed at their assimilation.[78] The genocide hypothesis remains, however, a minority view among historians, and is not endorsed by any nation or major organisation. Desmond Fernandes, a senior lecturer at De Montfort University, breaks the policy of the Turkish authorities into the following categories:[79]

- Forced assimilation program, which involved, among other things, a ban of the Kurdish language, and the forced relocation of Kurds to non-Kurdish areas of Turkey.

- The banning of any organizations opposed to category one.

- The violent repression of any Kurdish resistance.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In January 2013, the Turkish parliament passed a law that permits use of the Kurdish language in the courts, albeit with restrictions.[81][82] The law was passed by votes of the ruling AKP and the pro-Kurdish rights opposition party BDP, against criticism from the secularist CHP party and the nationalist MHP, with MHP and CHP[citation needed] deputies nearly coming to blows with BDP deputies over the law. In spite of their support in the parliament, the BDP was critical of the provision in the law that the defendants will pay for the translation fees and that the law applies only to spoken defense in court but not to a written defense or the pre-trial investigation.[83] According to one source[82] the law does not comply with EU standards.[which?] Deputy prime minister of Turkey Bekir Bozdağ replied to criticism of the law from both sides saying that the fees of defendants who does not speak Turkish will be paid by the state, while, those who speak Turkish yet prefer to speak in the court in another language will have to pay the fees themselves.[84] European Commissioner for Enlargement Stefan Füle welcomed the new law.[85]

In February 2013, Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said during a meeting with Muslim opinion leaders, that he has "positive views" about imams delivering sermons in Turkish, Kurdish or Arabic, according to the most widely spoken language among the mosque attendees. This move received support from Kurdish politicians and human rights groups.[86]

Against Arabs

[edit]Turkey has a history of strong anti-Arabism, which has been on a significant rise because of the Syrian refugee crisis.[14][15] Haaretz reported that anti-Arab racism in Turkey mainly affects two groups; tourists from the Gulf who are characterized as "rich and condescending" and the Syrian refugees in Turkey.[14] Haaretz also reported that anti-Syrian sentiment in Turkey is metastasizing into a general hostility toward all Arabs including the Palestinians.[14] Deputy Chairman of the İyi Party warned that Turkey risked becoming "a Middle Eastern country" because of the influx of refugees.[16]

Against Armenians

[edit]

Although it was possible for Armenians to achieve status and wealth in the Ottoman Empire, as a community, they were accorded a status as second-class citizens (under the Millet system)[87] and were regarded as fundamentally alien to the Muslim character of Ottoman society.[88] In 1895, demands for reform among the Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire lead to Sultan Abdul Hamid's decision to suppress them resulting in the Hamidian massacres in which up to 300,000 Armenians were killed and many more tortured.[89][90] In 1909, a massacre of Armenians in the city of Adana resulted in a series of anti-Armenian pogroms throughout the district resulting in the deaths of 20,000–30,000 Armenians.[91][92][93] During World War I, the Ottoman government massacred between 1 and 1.5 million Armenians in the Armenian genocide.[94][95][96][97] The position of the current Turkish government, however, is that the Armenians who died were casualties of the expected hardships of war, the casualties cited are exaggerated, and that the 1915 events could not be considered a genocide. This position has been criticized by international genocide scholars,[98] and by 28 governments, which have resolutions affirming the genocide.

"The new generations are being taught to see Armenians not as human, but [as] an entity to be despised and destroyed, the worst enemy. And the school curriculum adds fuel to the existing fires."

Some difficulties currently experienced by the Armenian minority in Turkey are a result of an anti-Armenian attitude by ultra-nationalist groups such as the Grey Wolves. According to Minority Rights Group, while the government officially recognizes Armenians as minorities but when used in public, this term denotes second-class status.[100] In Turkey, the term 'Armenian' has often been used as an insult. Kids are taught at a young age to hate Armenians and the "Armenian" and several people have been prosecuted for calling public figures and politicians as such.[101][102][103][104][99]

The term 'Armenian' is frequently used in politics to discredit political opponents.[107] In 2008, Canan Arıtman, a deputy of İzmir from the Republican People's Party (CHP), called President Abdullah Gül an 'Armenian'.[102][108] Arıtman was then prosecuted for "insulting" the president.[102][107][109] Similarly, in 2010, Turkish journalist Cem Büyükçakır approved a comment on his website claiming that President Abdullah Gül's mother was an Armenian.[110] Büyükçakır was then sentenced to 11 months in prison for “insulting President [Abdullah] Gül”.[110][111][112]

Hrant Dink, the editor of the Agos weekly Armenian newspaper, was assassinated in Istanbul on January 19, 2007, by Ogün Samast. He was reportedly acting on the orders of Yasin Hayal, a militant Turkish ultra-nationalist.[115][116] For his statements on Armenian identity and the Armenian genocide, Dink had been prosecuted three times under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code for "insulting Turkishness."[117][118] He had also received numerous death threats from Turkish nationalists who viewed his "iconoclastic" journalism (particularly regarding the Armenian genocide) as an act of treachery.[119]

Sevag Balikci, a Turkish soldier of Armenian descent, was shot dead on April 24, 2011, the day of the commemoration of the Armenian genocide, during his military service in Batman.[120] Through his Facebook profile, it was discovered that killer Kıvanç Ağaoğlu was an ultra-nationalist, and a sympathizer of nationalist politician Muhsin Yazıcıoğlu and Turkish agent / contract killer Abdullah Çatlı, who himself had a history of anti-Armenian activity, such as the Armenian Genocide Memorial bombing in a Paris suburb in 1984.[121][122][123][124] His Facebook profile also showed that he was a Great Union Party (BBP) sympathizer, a far-right nationalist party in Turkey.[121] Balıkçı's fiancée testified that Sevag told her over the phone that he feared for his life because a certain military serviceman threatened him by saying, "If war were to happen with Armenia, you would be the first person I would kill".[125][126]

İbrahim Şahin and 36 other alleged members of Turkish ultra-nationalist Ergenekon group were arrested in January, 2009 in Ankara. The Turkish police said the round-up was triggered by orders Şahin gave to assassinate 12 Armenian community leaders in Sivas.[127][128] According to the official investigation in Turkey, Ergenekon also had a role in the murder of Hrant Dink.[129]

On February 26, 2012, the Istanbul rally to commemorate the Khojaly massacre turned into an Anti-Armenian demonstration which contained hate speech and threats towards Armenia and Armenians.[131][132][133][134] Chants and slogans during the demonstration include: "You are all Armenian, you are all bastards", "bastards of Hrant can not scare us", and "Taksim Square today, Yerevan Tomorrow: We will descend upon you suddenly in the night."[131][132]

In February 2015, graffiti was discovered near the wall of an Armenian church in the Kadıköy district of Istanbul saying, "You’re Either Turkish or Bastards" and "You Are All Armenian, All Bastards".[135][136][137] It is claimed that the graffiti was done by organizing members of a rally entitled "Demonstrations Condemning the Khojali Genocide and Armenian Terror." The Human Rights Association of Turkey petitioned the local government of Istanbul calling it a "Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hate Against Armenians in Turkey".[135][138] In the same month banners celebrating the Armenian genocide were spotted in several cities throughout Turkey. They declared: "We celebrate the 100th anniversary of our country being cleansed of Armenians. We are proud of our glorious ancestors." (Yurdumuzun Ermenilerden temizlenişinin 100. yıldönümü kutlu olsun. Şanlı atalarımızla gurur duyuyoruz.)[130][139]

Against Assyrians

[edit]The Assyrians also shared a similar fate to that of the Armenians. The Assyrians also suffered in 1915 and they were massacred en masse.[140][141] The Assyrian genocide or the Seyfo (as it is known to Assyrians) reduced the population of the Assyrians of Anatolia and the Iranian plateau from about 650,000 before the genocide to 250,000 after the genocide.[142][143][144]

Discrimination continued well into the newly formed Turkish Republic. In the aftermath of the Sheikh Said rebellion, the Assyrian Orthodox Church was subjected to harassment by Turkish authorities, on the grounds that some Assyrians allegedly collaborated with the rebelling Kurds.[145] Consequently, mass deportations took place and Patriarch Mar Ignatius Elias III was expelled from Mor Hananyo Monastery which was turned into a Turkish barrack. The patriarchal seat was then transferred to Homs temporarily.

Assyrians historically couldn't become civil servants in Turkey and they couldn't attend military schools, become officers in the army or join the police.[146]

Against Afghans

[edit]Afghan refugees and migrants have accused Turkish security personnel of violent attacks, including lethal force against them for attempting to enter the country by shooting at them.[147] Turkish border guards have been accused of shooting and killing Afghans attempting to enter the country. Meanwhile, Turkish immigration officials have continued their efforts to deport millions of Afghan migrants living in the country.[148]

A 2023 research report published by a team of Turkish scholars explained the affiliation of Afghan migrants with crime in the country and reasons for public sentiments rising against them.[149]

A video surfaced online showing Turkish ultra-nationalists beating an Afghan man and was circulated on social media.[150]

Against Alevis

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Against Greeks

[edit]

Punitive Turkish nationalist exclusivist measures, such as a 1932 parliamentary law, barred Greek citizens living in Turkey from a series of 30 trades and professions from tailoring and carpentry to medicine, law and real estate.[151] The Varlık Vergisi tax imposed in 1942 also served to reduce the economic potential of Greek businesspeople in Turkey.[152] On 6–7 September 1955 anti-Greek riots were orchestrated in Istanbul by the Turkish military's Tactical Mobilization Group, the seat of Operation Gladio's Turkish branch; the Counter-Guerrilla. The events were triggered by the news that the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki, north Greece—the house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was born in 1881—had been bombed the day before.[152] A bomb planted by a Turkish usher of the consulate, who was later arrested and confessed, incited the events. The Turkish press conveying the news in Turkey was silent about the arrest and instead insinuated that Greeks had set off the bomb. Although the mob did not explicitly call for Greeks to be killed, over a dozen people died during or after the pogrom as a result of beatings and arson. Kurds, Jews, Armenians, Assyrians, Minority Muslims and Non-Muslim Turks were also harmed. In addition to commercial targets, the mob clearly targeted property owned or administered by the Greek Orthodox Church. 73 churches and 23 schools were vandalized, burned or destroyed, as were 8 asperses and 3 monasteries.

The pogrom greatly accelerated emigration of ethnic Greeks from Turkey, and the Istanbul region in particular. The Greek population of Turkey declined from 119,822 persons in 1927,[153] to about 7,000 in 1978.[154] In Istanbul alone, the Greek population decreased from 65,108 to 49,081 between 1955 and 1960.[153]

The Greek minority continues to encounter problems relating to education and property rights. A 1971 law nationalized religious high schools, and closed the Halki seminary on Istanbul's Heybeli Island which had trained Orthodox clergy since the 19th century. A later outrage was the vandalism of the Greek cemetery on Imbros on October 29, 2010. In this context, problems affecting the Greek minority on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos continue to be reported to the European Commission.[155]

As of 2007, Turkish authorities have seized a total of 1,000 immovables of 81 Greek organizations as well as individuals of the Greek community.[156] On the other hand, Turkish courts provided legal legitimacy to unlawful practices by approving discriminatory laws and policies that violated fundamental rights they were responsible to protect.[157] As a result, foundations of the Greek communities started to file complaints after 1999 when Turkey's candidacy to the European Union was announced. Since 2007, decisions are being made in these cases; the first ruling was made in a case filed by the Phanar Greek Orthodox College Foundation, and the decision was that Turkey violated Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which secured property rights.[157]

Against Jews

[edit]In the 1930s, groups publishing anti-Semitic journals were formed. Journalist Cevat Rıfat Atilhan published a journal in İzmir called Anadolu and which contained anti-Semitic writing.[25] When the publication was outlawed, Atilhan went to Germany and was entertained by Julius Streicher for months. In Der Stürmer, a publication by Streicher, a large article was published about Cevat Rifat Atilhan on 18 August 1934.[25] Upon returning to Turkey, Atilhan started the journal Milli İnkılap which was very similar to Der Stürmer. Consequently, it is argued that much of the anti-Semitic theories in Turkey stem from much of the opinions and material that Atilhan took from Germany.[25]

The Elza Niego affair was an event regarding the murder of a Jewish girl in Turkey named Elza Niego in 1927. During the funeral, a demonstration was held in opposition of the Turkish government which created an anti-Semitic reaction in the Turkish press.[158][159] Nine protestors were immediately arrested under the charge of offending "Turkishness".[159][160][161][162]

The 1934 Resettlement Law was a policy adopted by the Turkish government which set forth the basic principles of immigration.[163] Although the Law on Settlement was expected to operate as an instrument for Turkifying the mass of non-Turkish speaking citizens, it immediately emerged as a piece of legislation which sparked riots against non-Muslims, as evidenced in the 1934 Thrace pogroms against Jews in the immediate aftermath of the law's passage. With the law being issued on 14 June 1934, the Thrace pogroms began just over a fortnight later, on 3 July. The incidents seeking to force out the region's non-Muslim residents first began in Çanakkale, where Jews received unsigned letters telling them to leave the city, and then escalated into an antisemitic campaign involving economic boycotts and verbal assaults as well as physical violence against the Jews living in the various provinces of Thrace.[164] It is estimated that out of a total 15,000-20,000 Jews living in the region, more than half fled to Istanbul during and after the incidents.[165]

The Neve Shalom Synagogue in Istanbul has been attacked three times.[166] First on 6 September 1986, Arab militants killed 22 Jewish worshippers and wounded 6 during Shabbat services at Neve Shalom. This attack was blamed on the Palestinian militant Abu Nidal.[167][168][169] The Synagogue was hit again during the 2003 Istanbul bombings alongside the Beth Israel Synagogue, killing 20 and injuring over 300 people, both Jews and Muslims alike. Even though a local Turkish militant group, the Great Eastern Islamic Raiders' Front, claimed responsibility for the attacks, police claimed the bombings were "too sophisticated to have been carried out by that group",[167] with a senior Israeli government source saying: "the attack must have been at least coordinated with international terror organizations".[169]

In 2015, an Erdogan-affiliated news channel broadcast a two-hour documentary titled "The Mastermind" (a term which Erdogan himself had introduced to the public some months earlier), which forcefully suggested that it were "the mind of the Jews" that "rules the world, burns, destroys, starves, wages wars, organizes revolutions and coups, and establishes states within states."[170]

According to the Anti-Defamation League 71% of Turkish adults "harbor anti-Semitic views".[171]

Against Africans

[edit]A common perception among the Turkish society is that racism against black people in Turkey is not a big issue because the country does not have a history of colonialism or segregation as in many Western countries. On the contrary, sociologists such as Doğuş Şimşek strongly reject this point of view, stressing that this misperception resulted from the fact that Africans in Turkey often live in the shadows and Afro-Turks, the historical black population of Turkey, are mostly confined to tiny communities in Western Turkey.[172]

African immigrants, whose numbers were estimated to be 150,000 as of 2018 have reported to experience sexual abuse and discrimination based on racial grounds regularly in Turkey.[173][174]

Against Turks

[edit]In Turkey, one common habit is to assume one's ethnicity from the place of origin, often based on an inaccurate perception of the demographics of a specific area. Likewise, ethnic Turks who come from eastern parts of the country can be discriminated against based on the assumption that they are Kurds, even though they are not.[175] Many Syrian Turkmen who took refuge in the country face racism as other Syrian refugees.[176]

Discrimination against Turks whom are of religious sects besides the Sunni majority such as Alevis, Shias and other non-Sunni Turks is also widely reported.[177]

Turkish scholars have also illustrated the sub-cultural prejudices against other Turks. They have argued the so-called White Turks hold racist-like intent towards the so-called Black Turks because of sub-cultural differences.[178]

Against Romani, Domari, Lom and Abdals

[edit]Romani people, Domari, Abdals and Lom, have many problems in everyday life, e.g. in jobs, professions, as well as the report of mysterious death of a young east thracian Turkish Roma soldier in May 2021, who served his military service in Itlib, because he was a Rom, exclusion from corona aid 2020, exclusion from earthquake aid 2023, Domari Refugees of the Syrian civil war in Turkey, have big problems too. Expelled from places there live since century like Sulukule in 2007 and Bayramiç in 1970. Due to exclusion, many of this Groups deny their gypsy origins as much as possible and pretend to be Turks or Turkmen.[12][179][180][181][182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189][190][excessive citations]

See also

[edit]- Human rights in Turkey

- Minorities in Turkey

- Anti-Turkish sentiment

- Anti-Arab sentiment

- Environmental racism in Turkey

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Khojali: A Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hatred". Armenian Weekly. 22 February 2015.

- ^ Xypolia, Ilia (18 February 2016). "Racist Aspects of Modern Turkish Nationalism". Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies. 18 (2): 111–124. doi:10.1080/19448953.2016.1141580. hdl:2164/9172. ISSN 1944-8953. S2CID 147685130.

- ^ Björgo, Tore; Witte, Rob, eds. (1993). Racist violence in Europe. Basingstoke [etc.]: Macmillan Press. ISBN 9780312124090.

- ^ Arat, Zehra F. Kabasakal, ed. (2007). Human rights in Turkey. Foreword by Richard Falk. Philadelphia, Pa.: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812240009.

- ^ Lauren, Fulton (Spring 2008). "A Muted Controversy: Freedom of Speech in Turkey". Harvard International Review. 30 (1): 26–29. ISSN 0739-1854.

Free speech is now in a state reminiscent of the days before EU accession talks. Journalists or academics who speak out against state institutions are subject to prosecution under the aegis of loophole laws. Such laws are especially objectionable because they lead to a culture in which other, more physically apparent rights abuses become prevalent. Violations of freedom of expression can escalate into other rights abuses, including torture, racism, and other forms of discrimination. Because free speech is suppressed, the stories of these abuses then go unreported in what becomes a vicious cycle.

- ^ Gooding, Emily (2011). Armchair Guide to Discrimination: Religious Discrimination in Turkey. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781241797812.

- ^ Kenanoğlu, Pinar Dinç (2012). "Discrimination and silence: minority foundations in Turkey during the Cyprus conflict of 1974". Nations and Nationalism. 18 (2): 267–286. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2011.00531.x.

Comprehensive reading of the newspaper articles show that the negative attitude towards the non-Muslim minorities in Turkey does not operate in a linear fashion. There are rises and falls, the targets can vary from individuals to institutions, and the agents of discrimination can be politicians, judicial offices, government-operated organisations, press members or simply individuals in society.

- ^ Toktas, Sule; Aras, Bulent (Winter 2009). "The EU and Minority Rights in Turkey". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (4): 697–0_8. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165x.2009.tb00664.x. ISSN 0032-3195.

In the Turkish context, the solution to minority rights is to handle them through improvements in three realms: elimination of discrimination, cultural rights, and religious freedom. However, reforms in these spheres fall short of the spirit generated in the Treaty of Lausanne.

- ^ [2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

- ^ a b c Cirakman, Asli (2011). "Flags and traitors: The advance of ethno-nationalism in the Turkish self-image". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 34 (11): 1894–1912. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.556746. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 143287720.

- ^ Makogon, Kateryna (3 November 2022). "Roma in Turkey: discrimination, exclusion, deep poverty and deprivation". Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Romani, Domari, and Abdal earthquake victims face discrimination and hate crimes in Turkey". European Roma Rights Centre. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Lom or Bosha people from past to present". Agos. 13 February 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Palestinians Were Spared Turkey's Rising anti-Arab Hate. Until Now". Haaretz. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b Tremblay, Pinar (21 August 2014). "Anti-Arab sentiment on rise in Turkey". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Syrian refugees who were welcomed in Turkey now face backlash". NBC News. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Halis, Mujgan (13 November 2013). "Anti-Syrian sentiment on the rise in Turkey". Al-Monitor (in Turkish). Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Afghan Migrants in Turkey Worried About Increased Deportations". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ ANI; ANI (22 April 2022). "Videos of 'Pakistani perverts' cause outrage on social media in Turkey". ThePrint. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Soyturk, Kaan; Caglayan, Ceyda; Erkoyun, Ezgi (14 December 2022). "Influx of Russians drives up home prices in Turkish resort, prompts call for ban". www.reuters.com. Reuters.

- ^ "A tragedy for Ukraine, a housing crisis for Turkey". 7 May 2022.

- ^ "The Russian-Ukrainian War Has Increased House Rents in Antalya by 100 Percent – TURKISH RESIDENCE PERMIT, VISA". 28 March 2022.

- ^ "'Russians have overrun my city and now we can't afford to live'". 15 October 2023.

- ^ Icduygu, A., Toktas, S., & Soner, B. A. (2008). "The politics of population in a nation-building process: Emigration of non-Muslims from turkey." Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(2), 358–389.

- ^ a b c d Özbek, Sinan (2005). "Reflections on Racism in Turkey". Human Affairs. 15 (1): 84–95. doi:10.1515/humaff-2005-150111. ISSN 1210-3055. S2CID 259346739.

- ^ a b Ergin, Murat (2008). "'Is the Turk a White Man?' towards a Theoretical Framework for Race in the Making of Turkishness". Middle Eastern Studies. 44 (6): 832–833. doi:10.1080/00263200802425973. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 40262624. S2CID 144560316 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Ergin, Murat (2008), p.833

- ^ a b Yegen, Mesut (Autumn 2009). ""Prospective-Turks" or "Pseudo-Citizens:" Kurds in Turkey". Middle East Journal. 63 (4): 597–615. doi:10.3751/63.4.14. ISSN 0026-3141. S2CID 144559224.

- ^ Okutan, Çağatay (2004). Tek Parti Döneminde Azınlık Politikaları. Istanbul: Bilgi Universitesi. ISBN 978-9758557776.

- ^ Bein, Amit (9 November 2017). Kemalist Turkey and the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-107-19800-5.

- ^ The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s, Ilker Aytürk (Bilkent University, Ankara), Journal of Contemporary History, SAGE Pub., 2011 [1] p.326

- ^ Aytürk, Ilker (2011). "The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s". Journal of Contemporary History. 46 (2): 326. doi:10.1177/0022009410392411. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 41305314. S2CID 159678425 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Nihal Atsız, Reha Oğuz Türkkan ve Turancılar Davası - AYŞE HÜR". Radikal (in Turkish). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Bali, Rıfat N. (2012). Model Citizens of the State: The Jews of Turkey During the Multi-party Period. Lexington Books. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-61147-536-4.

- ^ a b c Cooper; Akcam, Belinda; Taner (Fall 2005). "Turks, Armenians, and the "G-Word"". World Policy Journal. 22 (3): 81–93. doi:10.1215/07402775-2005-4009. ISSN 0740-2775.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaya, Nurcan (2015). Kayacan, Gülay (ed.). Discrimination based on Colour, Ethnic Origin, Language, Religion and Belief in Turkey's Education System (PDF). Istanbul: Minority Rights Group International (MRG). ISBN 978-975-8813-78-0.

- ^ "Education system in Turkey criticised for marginalising ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities". Blog. Minority Rights Group International. 27 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Handbook of the Human Rights Agenda Association on Hate Crimes in Turkey Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine; accessed on 14 October 2009

- ^ Guler, Habib (17 October 2012). "Commission head: Turkey needs new regulations against hate crime". Zaman. Ankara. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ Şahan, İdil Engindeniz; Fırat, Derya; Şannan, Barış. "January-April 2014 Media Watch on Hate Speech and Discriminatory Language Report" (PDF). Hrant Dink Foundation.

- ^ Baydar, Yavuz (12 January 2009). "Hate speech and racism: Turkey's 'untouchables'on the rise". Zaman. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Hate speech and racism: Turkey’s ‘untouchables’ on the rise, August 30, 2010, Todayszaman "Hate speech and racism: Turkey's 'untouchables'on the rise". Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Chapter 2. How Muslims and Westerners View Each Other". PEW Research Center. 21 July 2011.

- ^ First report of ECRI on Turkey (1999)

- ^ a b c "Turkish Interior Ministry confirms 'race codes' for minorities". Hurriyet.

- ^ "Turkish youth overwhelmingly against 'other,' study says". Hürriyet Daily News. 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Dersim Massacre, 1937-1938 | Sciences Po Mass Violence and Resistance - Research Network". dersim-massacre-1937-1938.html. 19 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Christopher Houston, Islam, Kurds and the Turkish nation state, Berg Publishers, 2001, ISBN 978-1-85973-477-3, p. 102.

- ^ Freedom of the Press, Freedom of the Press 2010 Draft Report, p. 2. (in English)

- ^ Ahmet Alış, "The Process of the Politicization of the Kurdish Identity in Turkey: The Kurds and the Turkish Labor Party (1961–1971)", Atatürk Institute for Modern Turkish History, Boğaziçi University, p. 73. (in English)

- ^ Altan Tan, Kürt sorunu, Timaş Yayınları, 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-884-6, p. 275.[permanent dead link] (in Turkish)

- ^ Pınar Selek, Barışamadık, İthaki Yayınları, 2004, ISBN 978-975-8725-95-3, p. 109. (in Turkish)

- ^ Yusuf Mazhar, Cumhuriyet, 16 Temmuz 1930, ... Zilan harekatında imha edilenlerin sayısı 15.000 kadardır. Zilan Deresi ağzına kadar ceset dolmuştur... (in Turkish)

- ^ Ahmet Kahraman, ibid, p. 211, Karaköse, 14 (Özel muhabirimiz bildiriyor) ... (in Turkish)

- ^ Ayşe Hür, "Osmanlı'dan bugüne Kürtler ve Devlet-4" Archived 2011-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Taraf, October 23, 2008, Retrieved August 16, 2010. (in Turkish)

- ^ Ayşe Hür, "Bu kaçıncı isyan, bu kaçıncı harekât?" Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, Taraf, December 23, 2007, Retrieved August 16, 2010. (in Turkish)

- ^ Paul J. White, ibid, p. 79. (in English)

- ^ The Turkish crime of our century, Asia Minor Refugees Coordination Committee, p. 14. (in English)

- ^ Turkish text: Bu ülkede sadece Türk ulusu etnik ve ırksal haklar talep etme hakkına sahiptir. Başka hiç kimsenin böyle bir hakkı yoktur. Aslı astarı olmayan propagandalara kanmış, aldanmış, neticede yollarını şaşırmış Doğu Türkleridir., Vahap Coşkun, "Anayasal Vatandaşlık Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine", Köprü dergisi, Kış 2009, 105. Sayı. (in Turkish)

- ^ a b Levene, Mark (1998). "Creating a Modern 'Zone of Genocide': The Impact of Nation- and State-Formation on Eastern Anatolia, 1878-1923". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 12 (3): 393–433. doi:10.1093/hgs/12.3.393.

The persistence of genocide or near-genocidal incidents from the 1890s through the 1990s, committed by Ottoman and successor Turkish and Iraqi states against Armenian, Kurdish, Assyrian, and Pontic Greek communities in Eastern Anatolia, is striking. ... the creation of this "zone of genocide" in Eastern Anatolia cannot be understood in isolation, but only in light of the role played by the Great Powers in the emergence of a Western-led international system.

In the last hundred years, four Eastern Anatolian groups—Armenians, Kurds, Assyrians, and Greeks—have fallen victim to state-sponsored attempts by the Ottoman authorities or their Turkish or Iraqi successors to eradicate them. Because of space limitations, I have concentrated here on the genocidal sequence affecting Armenians and Kurds only, though my approach would also be pertinent to the Pontic Greek and Assyrian cases. - ^ "Resmi raporlarda Dersim katliamı: 13 bin kişi öldürüldü", Radikal, November 19, 2009. (in Turkish)

- ^ "The Suppression of the Dersim Rebellion in Turkey (1937-38) Page 4" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2013.

- ^ David McDowall, A modern history of the Kurds, I.B.Tauris, 2002, ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0, p. 209.

- ^ "DERSĐM '38 CONFERANCE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Turkey - Linguistic and Ethnic Groups". countrystudies.us.

- ^ Bartkus, Viva Ona, The Dynamic of Secession, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 90-91.

- ^ Çelik, Yasemin (1999). Contemporary Turkish foreign policy (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 3. ISBN 9780275965907.

- ^ Schleifer, Yigal (12 May 2005). "Opened with a flourish, Turkey's Kurdish-language schools fold". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Kanat, Kilic; Tekelioglu, Ahmet; Ustun, Kadir (2015). Politics and Foreign Policy in Turkey: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Washington D.C.: The SETA Foundation. pp. 32–5. ISBN 978-6054023547.

- ^ "Kurdish to be offered as elective course at universities". Today's Zaman. 6 January 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Class time for a 'foreign language' in Turkey". Hurriyet Daily News. 12 October 2010.

- ^ "First undergrad Kurdish department opens in SE". Hurriyet Daily News. 24 September 2011. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Kurds, Turkey: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.

- ^ Toumani, Meline. Minority Rules, New York Times, 17 February 2008

- ^ Aslan, Senem (2014). Nation-Building in Turkey and Morocco: Governing Kurdish and Berber Dissent. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1316194904.

- ^ Meho, Lokman I (2004). "Congressional Record". The Kurdish Question in U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary Sourcebook. Praeger/Greenwood. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-313-31435-3.

- ^ "Kurds in Turkey increasingly subject to violent hate crimes". DW. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove; Fernandes, Desmond (April 2008). "Kurds in Turkey and in (Iraqi) Kurdistan: a Comparison of Kurdish Educational Language Policy in Two Situations of Occupation". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3: 43–73. doi:10.3138/gsp.3.1.43.

- ^ "Gomidas Institute". www.gomidas.org.

- ^ "Turkish TV cuts politician during speech in Kurdish". CNN. 24 February 2009.

- ^ "Turkey allows Kurdish language in courts". Deutsche Welle. 25 January 2013.

- ^ a b Geerdink, Fréderike (24 January 2013). "Kurdish permitted in Turkish courts". Journalists in Turkey. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Butler, Daren (25 January 2013). "Turkey approves court reform, Kurds remain critical". Reuters.

- ^ "Scuffles at Parliament over defense in Kurdish". Hürriyet Daily News. 23 January 2013.

- ^ "EU Official Welcomes Use Of Mother Tongue In Court". haberler.com. 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Gov't move for delivery of sermons in local language receives applause". Today's Zaman. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4128-3592-3.

In it, Muslims had full legal and social rights, while non-Muslim "people of the book," that is, Jews and Christians, had a second-class subject status that entailed, among other things, higher taxes, exclusion from the military and political spheres, and strict limitations on legal rights.

- ^ "Communal Violence: The Armenians and the Copts as Case Studies," by Margaret J. Wyszomirsky, World Politics, Vol. 27, No. 3 (April 1975), p. 438

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2006) A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility p. 42, Metropolitan Books, New York ISBN 978-0-8050-7932-6

- ^ Hamidian Massacres, Armenian Genocide.

- ^ Raymond H. Kévorkian, "The Cilician Massacres, April 1909" in Armenian Cilicia, eds. Richard G. Hovannisian and Simon Payaslian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 7. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2008, pp. 339-69.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2012). "The Armenian Genocide". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (eds.). Century of Genocide. Routledge. pp. 117–56. ISBN 978-0-415-87191-4.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). "Adana Massacre". Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- ^ Levon Marashlian. Politics and Demography: Armenians, Turks, and Kurds in the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Zoryan Institute, 1991.

- ^ Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (eds.) Dictionary of Genocide. Greenwood Publishing, 2008, ISBN 0-313-34642-9, p. 19.

- ^ Noël, Lise. Intolerance: A General Survey. Arnold Bennett, 1994, ISBN 0-7735-1187-3, p. 101.

- ^ Schaefer, Richard T (2008), Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, p. 90.

- ^ Letter from the International Association of Genocide Scholars to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, June 13, 2005

- ^ a b Tremblay, Pinar (11 October 2015). "Grew up Kurdish, forced to be Turkish, now called Armenian". Al-Monitor.

- ^ "Minority Rights Group, Turkey > Armenians". Archived from the original on 8 May 2015.

- ^ Marchand, Laure; Perrier, Guillaume (2015). Turkey and the Armenian Ghost: On the Trail of the Genocide. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7735-9720-4.

- ^ a b c Özdoğan, Günay Göksu; Kılıçdağı, Ohannes (2012). Hearing Turkey's Armenians: Issues, Demands and Policy Recommendations (PDF). İstanbul: Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV). p. 26. ISBN 978-605-5332-01-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Yilmaz, Mehmet (26 March 2015). "Armenian as an 'insult'". Today's Zaman.

- ^ Aghajanian, Liana (2 February 2012). "Under Hrant Dink's Aura, a Turkish-Armenian Community Comes Into Its Own". Ararat. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Güneş, Deniz (20 February 2015). "İHD, İstanbul Valiliği'ni ırkçılığa karşı göreve davet etti" (in Turkish). Demokrat Haber. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "İHD: Mitingin amacı ırkçı nefreti kışkırtmaktır". Yüksekova Haber. 20 February 2015.

- ^ a b Schrodt, Nikolaus (2014). Modern Turkey and the Armenian Genocide: An Argument About the Meaning of the Past. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-319-04927-4.

- ^ "CHP deputy Arıtman unapologetic as Gül denies Armenian roots". Today's Zaman. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Bekdil, Burak. "How Turkish are the Turks?". Hurriyet.

- ^ a b "11-Month Prison Sentence for 'Gul is Armenian' Comment". Armenian Weekly. 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Haberin Yeri Site Kurucusu Büyükçakır'a 11 Ay Hapis". Bianet (in Turkish). 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Turkish Journalist, Publisher Receive 11-Month Prison Sentence for Calling Gul Armenian". Asbarez. 7 November 2010.

- ^ "Samast'a jandarma karakolunda kahraman muamelesi". Radikal (in Turkish). 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- ^ Watson, Ivan (12 January 2012). "Turkey remembers murdered journalist". CNN.

- ^ Harvey, Benjamin (24 January 2007). "Suspect in Journalist Death Makes Threat". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. [dead link]

- ^ "Turkish-Armenian writer shot dead". BBC News. 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

- ^ Robert Mahoney (15 June 2006). "Bad blood in Turkey" (PDF). Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2007.

- ^ "IPI Deplores Callous Murder of Journalist in Istanbul". International Press Institute. 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2007.

- ^ Committee to Protect Journalists (19 January 2007). "Turkish-Armenian editor murdered in Istanbul". Archived from the original on 25 January 2007.

Dink had received numerous death threats from nationalist Turks who viewed his iconoclastic journalism, particularly on the mass killings of Armenians in the early 20th century, as an act of treachery.

- ^ "Armenian private killed intentionally, new testimony shows". Today's Zaman. 27 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Halavurt: "Sevag 24 Nisan'da Planlı Şekilde Öldürülmüş Olabilir"". Bianet (in Turkish). 4 May 2011.

:Translated from Turkish: "On May 1, 2011, after investigating into the background of the suspect, we discovered that he was a sympathizer of the BBP. We also have encountered nationalist themes in his social networks. For example, Muhsin Yazicioglu and Abdullah Catli photos were present" according to Balikci lawyer Halavurt.

- ^ "Sevag Şahin'i vuran asker BBP'li miydi?" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Title translated from Turkish: What Happened to Sevag Balikci?". Radikal (in Turkish).

Translated from Turkish: "We discovered that he was a sympathizer of the BBP. We also have encountered nationalist themes in his social networks. For example, Muhsin Yazicioglu and Abdullah Catli photos were present" according to Balikci lawyer Halavurt."

- ^ "Sevag'ın Ölümünde Şüpheler Artıyor". Nor Zartonk (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

Title translated from Turkish: Doubts emerge on the death of Sevag

- ^ "Fiancé of Armenian soldier killed in Turkish army testifies before court". News.am. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Nişanlıdan 'Ermenilerle savaşırsak ilk seni öldürürüm' iddiası". Sabah (in Turkish). 6 April 2012.

Title Translated from Turkish: From the fiance: If we were to go to war with Armenia, I would kill you first"

- ^ "Turkish police uncover arms cache, The Wall Street Journal, January 10, 2009".

- ^ "E.I.R. GmbH: Aktuelle Meldungen". news.eirna.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Montgomery, Devin (12 July 2008). "Turkey arrests two ex-generals for alleged coup plot". JURIST.

- ^ a b Barsoumian, Nanore (23 February 2015). "Banners Celebrating Genocide Displayed in Turkey". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ a b "Azeris mark 20th anniversary of Khojaly Massacre in Istanbul". Hurriyet. 26 February 2012.

One banner carried by dozens of protestors said, "You are all Armenians, you are all bastards."

- ^ a b "Inciting Hatred: Turkish Protesters Call Armenians 'Bastards'". Asbarez. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

'Mount Ararat will Become Your Grave' Chant Turkish Students

- ^ "Khojaly Massacre Protests gone wrong in Istanbul: ' You are all Armenian, you are all bastards '". National Turk. 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Protests in Istanbul: "You are all Armenian, you are all bastards"". LBC International. 26 February 2012.

- ^ a b "İHD: Hocalı mitinginin amacı ırkçı nefreti kışkırtmak". IMC. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

- ^ Gunes, Deniz (20 February 2015). "Kadıköy esnafına ırkçı bildiri dağıtıldı" (in Turkish). Demokrat Haber. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "İHD: Mitingin amacı ırkçı nefreti kışkırtmaktır" (in Turkish). Yüksekova Haber. 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Khojali: A Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hatred". Armenian Weekly. 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Irkçı afişte 1915 itirafı!". Demokrat Haber (in Turkish). 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Aprim, Frederick A. (2006). Assyrians : from Bedr Khan to Saddam Hussein : driving into extinction the last Aramaic speakers (2. ed.). [United States]: F.A. Aprim. ISBN 9781425712990.

- ^ Hovanissian, Richard (2007). The Armenian genocide : cultural and ethical legacies (2. print. ed.). New Brunswick (N.J.): Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412806190.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294.

- ^ Gaunt, Massacres, Resistance, Protectors, pp. 21-28, 300-3, 406, 435.

- ^ Sonyel, Salahi R. (2001). The Assyrians of Turkey victims of major power policy. Ankara: Turkish historical Society. ISBN 9789751612960.

- ^ J. Joseph, Muslim-Christian relations and Inter-Christian rivalries in the Middle East, Albany, 1983, p.102.

- ^ H.Soysü, Kavimler Kapisi-1, Kaynak Yayınları, Istanbul, 1992.p.81.

- ^ Yeung, Peter (14 October 2021). "Afghan refugees accuse Turkey of violent illegal pushbacks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (23 August 2021). "Afghan Refugees Find a Harsh and Unfriendly Border in Turkey". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Uluğ, Özden Melis, et al. "Attitudes towards Afghan refugees and immigrants in Turkey: A Twitter analysis." Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology 5 (2023): 100145.

- ^ "Turkish far-right group beat Afghan man and shared video on social media – Turkish Minute". 30 December 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Vryonis, Speros (2005). The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. New York: Greekworks.com, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9747660-3-4.

- ^ a b Güven, Dilek (6 September 2005). "6–7 Eylül Olayları (1)". Radikal (in Turkish).

- ^ a b "Η μειονότητα των Ορθόδοξων Χριστιανών στις επίσημες στατιστικές της σύγχρονης Τουρκίας και στον αστικό χώρο" [The minority of Orthodox Christians in the official statistics of modern Turkey and in the urban area] (in Greek). Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Kilic, Ecevit (7 September 2008). "Sermaye nasıl el değiştirdi?". Sabah (in Turkish).

6-7 Eylül olaylarından önce İstanbul'da 135 bin Rum yaşıyordu. Sonrasında bu sayı 70 bine düştü. 1978'e gelindiğinde bu rakam 7 bindi.

- ^ "Turkey 2007 Progress Report, Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2007–2008" (PDF). Commission Stuff Working Document of International Affairs. p. 22.

- ^ Kurban, Hatem, 2009: p. 48

- ^ a b Kurban, Hatem, 2009: p. 33

- ^ Benbassa, Esther; Rodrigue, Aron (1999). Sephardi Jewry: a history of the Judeo-Spanish community, 14th--20th centuries (1. California paperback ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520218222.

- ^ a b "New Trial Ordered for Nine Constantinople Jews Once Acquitted". Jewish News Archive. 16 January 1928.

- ^ "Turkish Jewry Agitated Over Murder Case". Canadian Jewish Review. 7 October 1927. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

- ^ Kalderon, Albert E. (1983). Abraham Galanté : a biography. New York: Published by Sepher-Hermon Press for Sephardic House at Congregation Shearith Israel. p. 53. ISBN 9780872031111.

- ^ "TURKEY: Notes, Aug. 29, 1927". Time. 29 August 1927. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010.

- ^ Çağatay, Soner 2002 'Kemalist dönemde göç ve iskan politikaları: Türk kimliği üzerine bir çalışma' (Policies of migration and settlement in the Kemalist era: a study on Turkish identity), Toplum ve Bilim, no. 93, pp. 218-41.

- ^ Levi, Avner. 1998. Turkiye Cumhuriyetinde Yahudiler (Jews in the Republic of Turkey), Istanbul: Iletisim Yayınları

- ^ Karabatak, Haluk 1996 ‘Turkiye azınlık tarihine bir katkı: 1934 Trakya olayları ve Yahudiler’ (A contribution to the history of minorities in Turkey: the 1934 Thracian affair and the Jews), Tarih ve Toplum, vol. 146, pp. 68-80.

- ^ Helicke, James C. (15 November 2003). "Dozens killed as suicide bombers target Istanbul synagogues". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011.

- ^ a b Arsu, Sebnem; Filkins, Dexter (16 November 2003). "20 in Istanbul Die in Bombings At Synagogues". The New York Times.

- ^ Reeves, Phil (20 August 2002). "Mystery surrounds 'suicide' of Abu Nidal, once a ruthless killer and face of terror". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Bombings at Istanbul Synagogues Kill 23". Fox News. 16 November 2003. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Unraveling the AKP's 'Mastermind' conspiracy theory". Al-Monitor. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "There's a new bogeyman in Turkey, and, for a change, he's not a Jew". The Times of Israel.

- ^ "Light shed on lives of Africans in Istanbul - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "African businesspeople earn success in Istanbul - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Türkiye'de Afrikalı göçmenler: Bize insan değilmişiz gibi bakılıyor". euronews (in Turkish). 18 September 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Kılınç, Sevim. "Kadınlar Ayrımcılığı Anlatıyor". bianet. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Kemal, Levent. "Syrians increasingly choosing to leave Turkey as xenophobia grows". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Tanyeri-Erdemir, T., Çitak, Z., Weitzhofer, T., & Erdem, M. (2013). Religion and discrimination in the workplace in Turkey: Old and contemporary challenges. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 13(2-3), 214-239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229113496701

- ^ *DEMIRALP, SEDA. “White Turks, Black Turks? Faultlines beyond Islamism versus Secularism.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 3, 2012, pp. 511–24. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41507184. Accessed 2 Jan. 2025.

- ^ Özateşler, Gül (2017). "Multidimensionality of exclusionary violence". Ethnicities. 17 (6): 792–815. doi:10.1177/1468796813518206. JSTOR 26413989. S2CID 145807312.

- ^ "We Are Here!" (PDF). ercc.org. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Discrimination against Roma in Turkey increased during the pandemic: Report". 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Interview with the Turkish Roma musician ″Balik″ Ayhan Kucukboyaci: ″We Roma are more than just entertainers″ - Qantara.de". Qantara.de - Dialogue with the Islamic World. 22 October 2015.

- ^ "Roma in Turkey: Discrimination, exclusion, deep poverty and deprivation". 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Istanbul's ancient Roma community falls victim to building boom". Reuters. 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Turkish Romani community expects 'concrete steps' on its problems". Daily Sabah. 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Caner Sarmaşık". Duvar.

- ^ "Roma and representative justice in Turkey" (PDF). ethos-europe.eu. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Roma in Turkey suffer from lack of work, hunger, and extreme poverty, study shows". 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Invisible and Forgotten: Syrian Domari Refugees in Turkey".

- ^ "Lom or Bosha people from past to present". 13 February 2017.

External links

[edit]- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance reports on Turkey

- "Race and racism in modern Turkey". Bülent Gökay. Open Democracy.

- "Alevis in Turkey: A History of Persecution". Uzay Bulut. Amrneian National Committee of America. 21 November 2016.

- Hate Crimes in Turkey; Documentation prepared by the Democratic Turkey Forum, cases between 2007 and 2009]

- US Department of State: Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (country reports)

- European Commission for Enlargement

- Progress Reports on Turkey (1998 - 2005)

- Progress Report 2009

- Turkey Press Freedom Website covering press freedom situation in Turkey by SEEMO

- Human Rights Watch Reports on Turkey

- Amnesty International Library Archived 2015-02-17 at the Wayback Machine you can search for Reports on Turkey

- Reports and Investigations of Mazlumder about Turkish Human Rights

- Questions and Answers; Human Rights in Turkey, Human Rights Agenda Association Archived 2021-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Database on Refugee Rights in Turkey

- Hate Crimes in Turkey; Documentation prepared by the Democratic Turkey Forum, cases between 2007 and 2009