Hồng Bàng dynasty

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (June 2021) |

State of Xích Quỷ 赤鬼 (legendarily 2879–2524 BC) State of Văn Lang 文郎 (legendarily 2524–258 BC) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||

| Capital | Ngàn Hống (2879 BC – 2524 BC)[1] Nghĩa Lĩnh (29th c. BC)[1] Phong Châu (2524 – 258 BC)[2][3] | ||||||

| Religion | Animism, folk religion | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| King | |||||||

• 2879–2794 BC | Hùng Vương I (first) | ||||||

• 408–258 BC | Hùng Vương XVIII (last) | ||||||

| Historical era | Ancient history, Bronze Age, Iron Age | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Vietnam China | ||||||

The Hồng Bàng period (Vietnamese: thời kỳ Hồng Bàng),[4] also called the Hồng Bàng dynasty,[5] was a legendary ancient period in Vietnamese historiography, spanning from the beginning of the rule of Kinh Dương Vương over the kingdom of Văn Lang (initially called Xích Quỷ) in 2879 BC until the conquest of the state by An Dương Vương in 258 BC. Vietnamese history textbooks claim that this state was established in the 7th century BC on the basis of the Dong Son culture.

The 15th-century Vietnamese chronicle Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Đại Việt, The Complete History) claimed that the period began with Kinh Dương Vương as the first Hùng king (Vietnamese: Hùng Vương), a title used in many modern discussions of the ancient Vietnamese rulers of this period.[6] The Hùng king was the absolute monarch of the country and, at least in theory, wielded complete control of the land and its resources. The Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư also recorded that the nation's capital was Phong Châu (in present-day Phú Thọ Province in northern Vietnam) and alleged that Văn Lang was bordered to the west by Ba-Shu (present-day Sichuan), to the north by Dongting Lake (Hunan), to the east by the South China Sea and to the south by Champa.[7]

Origin of name

[edit]The name Hồng Bàng is the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation of characters "鴻龐" assigned to this dynasty in early Vietnamese-written histories in Chinese; its meaning is supposedly a mythical giant (龐) bird (鴻).[8]

French linguist Michel Ferlus (2009)[9] includes 文郎 Văn Lang (Old Chinese: ZS *mɯn-raːŋ; B&S *mə[n]-C.rˤaŋ) in the word-family *-ra:ŋ "human being, person" of Southeast Asian ethnonyms across three linguistic families, Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, together with:

- The ethnonym Maleng of a Vietic people living in Vietnam and Laos; Ferlus suggests that Vietic *m.leŋ is the "iambic late form" of *m.ra:ŋ.

- A kingdom north of today-Cambodia, Chinese: 堂明 Táng-míng in Sānguózhì and later Dào-míng 道明 in Tang documents;

- A kingdom subjected by Jayavarman II in the 8th century, known as Maleṅ [məlɨə̆ŋ] in Pre-Angkorian and Malyaṅ [məlɨə̆ŋ] in Angkorian Khmer; the kingdom's name is phonetically connected with Maleng, yet nothing further is conclusive.

- The ethnonym မြန်မာ Mraṅmā (1342); in Chinese transcription 木浪: OC *moːɡ-raːŋs → MC *muk̚-lɑŋᴴ → Mandarin Mù-làng.

- Malayic *ʔuʀaŋ "human being, person".

There also exists a phonetically similar Proto-Mon-Khmer etymon: *t₂nra:ŋ "man, male".[10]

The earliest historical mentions of Văn Lang, however, just had been recorded in Chinese-language documents, dated back to the Tang dynasty (7th- to 9th-century), about the area of Phong Châu (Phú Thọ).[11][12][13][14] However, Chinese records also indicated that another people, who lived elsewhere, were also called Văn Lang.[15][16]

History

[edit]

Pre-dynastic

[edit]The area now known as Vietnam has been inhabited since Palaeolithic times, with some archaeological sites in Thanh Hóa Province reportedly dating back around half a million years ago.[17] The prehistoric people had lived continuously in local caves since around 6000 BC, until more advanced material cultures developed.[18] Some caves are known to have been the home of many generations of early humans.[19] As northern Vietnam was a place with mountains, forests, and rivers, the number of tribes grew between 5000 and 3000 BC.[20]

During a few thousand years in the Late Stone Age, the inhabitant populations grew and spread to every part of Vietnam. Most ancient people were living near the Hồng (Red), Cả and Mã rivers. The Vietnamese tribes were the primary tribes at this time.[20] Their territory included modern meridional territories of China to the banks of the Hồng River in the northern territory of Vietnam. Centuries of developing a civilization and economy based on the cultivation of irrigated rice encouraged the development of tribal states and communal settlements.[citation needed]

Xích Quỷ Kingdom

[edit]Legend describes a significant political event occurred when Lộc Tục came into power in 2879 BC.[21] Lộc Tục was recorded as a descendant of the mythical ruler Shennong.[22] He consolidated the other tribes and succeeded in grouping all the vassal states (or autonomous communities) within his territory into a unified nation. Lộc Tục proclaimed himself Kinh Dương Vương and called his newly born nation Xích Quỷ. In the Complete Annals of Đại Việt (Vietnamese: Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, chữ Hán: 大越史記全書), states that,

帝明於是立帝宜爲嗣、治北方、封王爲涇陽王、治南方、號赤鬼國。

Đế Minh ư thị lập Đế Nghi vi tự, trị Bắc phương, phong vương vi Kinh Dương Vương, trị Nam phương, hiệu Xích Quỷ quốc.

Đế Minh mới lập Đế Nghi là con nối ngôi, cai quản phương Bắc, phong cho vua làm Kinh Dương Vương, cai quản phương Nam, gọi là nước Xích Quỷ.

Đế Minh (Great-grandson of the Yan Emperor) appointed Đế Nghi as his successor, to govern the northern region, and conferred the title of Kinh Dương Vương upon him [Lộc Tục], to govern the southern region, known as the country of Xích Quỷ.

The name Xích Quỷ 赤鬼 is derived from Sino-Vietnamese xích 赤 "red" and quỷ 鬼 "demon". The meaning of the name is from Twenty-Eight Mansions, where 鬼 quỷ refers to the constellation 鬼宿 (Sino-Vietnamese: Quỷ tú, Vietnamese: sao Quỷ) which lies in the South (a common motif of Vietnamese place names). Red 赤 is associated with Vermilion Bird of the South (Sino-Vietnamese: Chu Tước, chữ Hán: 朱雀).

Lộc Tục inaugurated the earliest monarchical regime as well as the first ruling family by heirdom in Vietnam's history. He is regarded as the ancestor of the Hùng kings, as the founding father of Vietnam, and as a Vietnamese cultural hero who is credited with teaching his people how to cultivate rice.[citation needed]

Văn Lang Kingdom

[edit]Starting from the third Hùng dynasty since 2524 BC, the kingdom was renamed Văn Lang, and the capital was set up at Phong Châu (in modern Việt Trì, Phú Thọ) at the juncture of three rivers where the Red River Delta begins from the foot of the mountains. The evidence that the Vietnamese knew how to calculate the lunar calendar by carving on stones dates back to 2200–2000 BC. Parallel lines were carved on the stone tools as a counting instrument involving the lunar calendar.[18][better source needed]

According to Vietnamese legend, at one point, Văn Lang had a war against Shang-China invasion, which Văn Lang came out victorious thanks to general Gióng.[citation needed]

The Hồng Bàng epoch finally ended in the middle of the third century BC on the advent of the military leader Thục Phán's conquest of Văn Lang, dethroning the last Hùng king.[citation needed]

Âu Lạc Kingdom

[edit]Văn Lang ended 258 BC when Thục Phán led the Âu Việt tribes to overthrow the last Hùng king in approximately 258 BC. After conquering Văn Lang, Thục Phán united the Lạc Việt tribes with the Âu Việt tribes to form a new kingdom of Âu Lạc. He proclaimed himself An Dương Vương and built his capital and citadel, Cổ Loa Citadel, in the modern-day Dong Anh district of Hanoi.[23][24]

Organization

[edit]The first Hùng King established the first "Vietnamese" state in response to the needs of co-operation in constructing hydraulic systems and in struggles against their enemies. This was a very primitive form of a sovereign state with the Hùng king on top and under him a court consisted of advisors – the lạc hầu.[25] The country was composed of fifteen bộ "regions", each ruled by a lạc tướng;[25] usually the lạc tướng was a member of the Hùng kings' family. Bộ comprised the agricultural hamlets and villages based on a matriarchal clan relationship and headed by a bộ chính, usually a male tribal elder.[25]

The Tale of the Hồng Bàng Clan claimed that Hùng kings had named princesses as "mỵ nương" (From Tai mae nang, which means princess), and prince as quan lang (From Muong word for Muong noble throughout the time).[26]

Semi-historical source described Văn Lang's northern border stretched to the southern part of present-day Hunan, and the southern border stretched to the Cả River delta, including parts of modern Guangxi, Guangdong and Northern Vietnam.[25] Such claims haven't been proved by archeological research.

According to Trần Trọng Kim's book, Việt Nam sử lược (A Brief History of Vietnam), the country was divided into 15 regions as in the table below.[27] However, they're in fact taken from Sino-Vietnamese names of later commanderies established by the Chinese in northern Vietnam.

| Name | Present-day location |

|---|---|

| Phong Châu (King's capital) | Phú Thọ Province |

| Châu Diên (朱鳶) | Sơn Tây Province |

| Phúc Lộc (福祿) | Sơn Tây Province |

| Tân Hưng (新興) | Hưng Hóa (part of Phú Thọ Province) and Tuyên Quang Province |

| Vũ Định (武定) | Thái Nguyên Province and Cao Bằng Province |

| Vũ Ninh (武寧) | Bắc Ninh Province |

| Lục Hải (陸 海) | Lạng Sơn Province |

| Ninh Hải (寧海) | Quảng Yên (a part of Quảng Ninh Province) |

| Dương Tuyên (陽泉) | Hải Dương Province |

| Giao Chỉ (交趾) | Hà Nội, Hưng Yên Province, Nam Định Province and Ninh Bình Province |

| Cửu Chân (九真) | Thanh Hóa Province |

| Hoài Hoan (懷驩) | Nghệ An Province |

| Việt Thường (越 裳) | Quảng Bình Province and Quảng Trị Province |

| Cửu Đức (九德) | Hà Tĩnh Province |

| Bình Văn (平文) | Ninh Binh from Day River to Mount Tara Diep |

Culture and economy

[edit]Agriculture

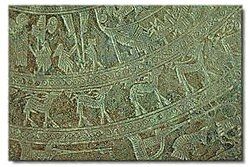

[edit]The economy was based predominantly on rice paddy cultivation, and also included handicrafts, hunting and gathering, husbandry and fishing. Especially, the skill of bronze casting was at a high level. The most famous relics are Đông Sơn Bronze Drums on which are depicted houses, clothing, customs, habits, and cultural activities of the Hùng era.

The Hùng Vươngs ruled Văn Lang in feudal fashion with the aid of the Lạc Tướng, who controlled the communal settlements around each irrigated area, organized construction and maintenance of the dikes, and regulated the supply of water. Besides cultivating rice, the people of Văn Lang grew other grains and beans and raised stock, mainly buffaloes, chickens, and pigs. Pottery-making and bamboo-working were highly developed crafts, as were basketry, leather-working, and the weaving of hemp, jute, and silk.

From 2000 BC, people in modern-day North Vietnam developed a sophisticated agricultural society, probably through learning from the Shang dynasty or the Laotian. The tidal irrigation of rice fields through an elaborate system of canals and dikes started by the sixth century BC.[28] This type of sophisticated farming system would come to define Vietnamese society. It required tight-knit village communities to collectively manage their irrigation systems. These systems in turn produced crop yields that could sustain much higher population densities than competing methods of food production.[29]

Bronze tools

[edit]

By about 1200 BC, the development of wet-rice cultivation and bronze casting in the Mã River and Red River plains led to the development of the Đông Sơn culture, notable for its elaborate bronze drums. The bronze weapons, tools, and drums of Đông Sơn sites show a Southeast Asian influence that indicates an indigenous origin for the bronze-casting technology. Many small, ancient copper mine sites have been found in northern Vietnam. Some of the similarities between the Đông Sơn sites and other Southeast Asian sites include the presence of boat-shaped coffins and burial jars, stilt dwellings, and evidence of the customs of betel-nut-chewing and teeth-blackening.

Pottery

[edit]The period between the end of the third millennium and the middle of the first millennium BC produced increasingly sophisticated pottery of the pre-Dong Son cultures of northern Viet Nam and the pre-Sa Huỳnh cultures of southern Vietnam. This period saw the appearance of wheel-made pottery, although the use of the paddle and anvil remained significant in manufacture.[30] Vessel surfaces are usually smooth, often polished, and red slipping is common. Cord-marking is present in all cultures and forms a fairly high percentage of sherdage[definition needed]. Complex incised decoration also developed with rich ornamental designs, and it is on the basis of incised decoration that Vietnamese archaeologists distinguish the different cultures and phases one from another.

The pottery from the successive cultural developments in the Red River Valley is the most well known. Vietnamese archaeologists here discern three pre-Đông Son cultures: Phùng Nguyên, Đồng Đậu, and Gò Mun. The pottery of these three cultures, despite the use of different decorative styles, has features that suggest a continuity of cultural development in the Red River Valley. In the Ma River Valley in Thanh Hóa Province, Vietnamese archaeologists also recognize three pre-Dong Son periods of cultural development: Con Chan Tien, Dong Khoi (Bai Man) and Quy Chu. In the areas stretching from the Red to the Cả River valleys, all the local cultures eventually developed into the Đông Sơn culture, which expanded over an area much larger than that of any previous culture and Vietnamese archaeologists believe that it had multiple regional sources. For instance, while Đông Sơn bronzes are much the same in different regions of northern Viet Nam, the regional characters of the pottery are fairly marked. On the whole, Đông Sơn pottery has a high firing temperature and is varied in form, but decorative patterns are much reduced in comparison with preceding periods, and consist mainly of impressions from cord-wrapped or carved paddles. Incised decoration is virtually absent.

Demographics

[edit]Contemporary Vietnamese historians have established the existence of various ethnic minorities now living in the highlands of North and Central Vietnam during the early phase of the Hồng Bàng dynasty.[31]

Chronology

[edit]The history of the Hồng Bàng period is split according to the rule of each Hùng king.[32] The dating of events is still a subject of research.[33] The date ranges are conservative date estimates for the known periods:[33] The lines of kings are in the order of the baguas and Heavenly Stems.

|

|

|

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Not in official histories, but in the unofficial Ngọc phả Hùng Vương "Hùng kings' Jade Genealogies". Phan Duy Kha (2012) "'Decoding' the Hung Kings' Jade Genealogies". Publisher: Bảo Tàng Lịch Sử Quốc Gia (Vietnamese National Museum of History)

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, "Records about the Hồng Bàng clan - Hung Kings" quote: "貉龍君之子也〈缺諱〉。都峯州〈今白鶴縣是也〉。" translation: "Lạc Long Quân's son (taboo name unknown) established his capital in Phong Châu, (now in Bạch Hạc prefecture)"

- ^ Anh Thư Hà, Hò̂ng Đức Trà̂n (2000). A brief chronology of Vietnam's history p. 4 quote: "while the remaining sons followed their father to the sea in the South, except for the eldest who was assigned to succeed his father as the next King Hùng. King Hùng named his country Văn Lang with Phong Châu (Bạch Hạc district, Phú Thọ ..."

- ^ Dror, p. 33 & 254 "Hồng Bàng period"

- ^ Pelley, p. 151

- ^ Tucker, Oxford Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War

- ^ "ĐVSKTT NK 1 - Viet Texts". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- ^ Thích Nhất Hạnh, Master Tang Hoi: First Zen Teacher in Vietnam and China – 2001 Page 1 "At that time the civilization of northern Vietnam was known as Van Lang (van means beautiful, and lang means kind and healing, like a good doctor). The ruling house of Van Lang was called Hong Bang, which means a kind of huge bird."

- ^ Michel Ferlus. "Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia". 42nd International Conference on SinoTibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009. pp. 4-5

- ^ Shorto, H. A Mon-Khmer Comparative Dictionary, Ed. Paul Sidwell, 2006. #692. p. 217

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Du You, Tongdian, Vol. 184 "峰州(今理嘉寧縣。)古文朗國,有文朗水。亦陸梁地。" translation: "Feng province (now Jianing prefecture) [was] the ancient Wenlang nation; there was the Wenlang river; also a wanderers' land."

- ^ Taiping Yulan "Provinces, Districts, and Divisions 18", Section: Lingnan Circuit" 《方輿志》曰:峰州,承化郡。古文郎國,有文郎水。亦陸梁地。" Translation: "'Geographical Almanacs' said: Feng province, Shenghua district. It was the ancient Wenlang nation; there was the Wenlang river; also a wanderers' land...

- ^ Yuanhe Maps and Records of Prefectures and Counties vol .38 "峯州承化下... 古夜(!)郎國之地按今新昌縣界有夜(!)郎溪" translation: "Feng province, lower Shenghua... Territory of the ancient Ye(!)lang nation. Next to the border of the current Xinchang prefecture, there is the Ye(!)lang brook." Note: not to be confused with the Yelang Kingdom in today Guizhou, China

- ^ Taiping Yulan "Provinces, Districts, and Divisions 18", Section: Lingnan Circuit"《林邑記》曰:蒼梧以南有文郎野人,居無室宅,依樹止宿,食生肉,采香為業,與人交易,若上皇之人。'Records of Linyi' said: From Cangwu Commandery to the south there are the wild people of Wenlang. They don't dwell in houses, use large trees as their resting places, eat raw meat; their profession is fragrance-gathering and they trade with other peoples, like people during the Sovereigns' time.'

- ^ Li Daoyuan, Commentary on the Water Classic Chapter 36 quote: "《林邑記》曰:渡比景至朱吾。朱吾縣浦,今之封界,朱吾以南,有文狼人,野居無室宅,依樹止宿,食生魚肉,採香為業,與人交市,若上皇之民矣。縣南有文狼究,下流逕通。" translation: "'Records of Linyi' said: Crossing Bijing to Zhouwu. Zhouwu prefecture's shores are the present borders. From Zhouwu to the south there were the Wenlang people. They dwell in the wilderness, not houses, use large trees as their resting places, eat raw meat and fish, their profession is fragrance-gathering and they trade with other peoples at the markets. Like how people lived during the time of the Sovereigns. To the south of the prefecture there is the Wenlang rapid; its lower reach is a narrow flow."

- ^ "Mission Atlas Project – VIETNAM – Basic Facts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ^ a b Ancient calendar unearthed Archived 2014-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ 6,000-year-old tombs unearthed in northeast Vietnam Archived 2014-02-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- ^ a b Lamb, p. 52

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên. "Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt". Viet Texts. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Vu, Hong Lien (2016). Rice and Baguette: A History of Food in Vietnam. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780237046.

- ^ Ray, Nick; et al. (2010), "Co Loa Citadel", Vietnam, Lonely Planet, p. 123, ISBN 9781742203898.

- ^ Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 13, 14. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- ^ a b c d Khâm định Việt sử thông giám cương mục, Vol. 1

- ^ Kelley (2016), p. 172.

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim (2005). Việt Nam sử lược (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City General Publishing House. p. 18.

- ^ Carr, Karen (October 15, 2017). "History of Vietnam from the Stone Age to today". quatr.us.

- ^ eHistory, Ohio State University. Guilmartin, John. "America and Vietnam: The Fifteen Year War." 1991. New York: Military Press.

- ^ Hoang and Bui 1980

- ^ Phan Huy Lê, Trần Quốc Vượng, Hà Văn Tấn, Lương Ninh, p. 99

- ^ Tăng Dực Đào, p. 7

- ^ a b Vuong Quan Hoang and Tran Tri Dung, p. 64

- ^ a b c d Ngô Văn Thạo, p. 823-824

Sources

[edit]- Bayard, D. T. 1977. Phu Wiang pottery and the prehistory of Northeastern Thailand. MQRSEA 3:57–102.

- Dror, Olga (2007). Cult, Culture, and Authority: Princess Liẽu Hạnh in Vietnamese.

- Heekeren, H. R. van. 1972. The Stone Age of Indonesia. The Hague: Nijhoff.

- Hoang Xuan Chinh and Bui Van Tien 1980. The Dongson Culture and Cultural Centers in the Metal Age in Vietnam

- Kelley, Liam C. (2016), "Inventing Traditions in Fifteenth-century Vietnam", in Mair, Victor H.; Kelley, Liam C. (eds.), Imperial China and its southern neighbours, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 161–193, ISBN 978-9-81462-055-0

- Lamb, David. Vietnam, Now: A Reporter Returns. PublicAffairs, 2008.

- Lévy, P. 1943. Recherches préhistoriques dans la région de Mlu Prei. PEFEO 30.

- Mourer, R. 1977. Laang Spean and the prehistory of Cambodia. MQRSEA 3:29–56.

- Ngô Văn Thạo (2005). Sổ tay báo cáo viên năm 2005. Hà Nội: Ban tư tưởng – văn hóa trung ương, Trung tâm thông tin công tác tư tưởng, 2005. 495 p. : col. ill.; 21 cm.

- Peacock, B. A. V. 1959. A short description of Malayan prehistoric pottery. AP 3 (2): 121–156.

- Pelley, Patricia M. Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past 2002.

- Phan Huy Lê, Trần Quốc Vượng, Hà Văn Tấn, Lương Ninh (1991), Lịch sử Việt Nam, volume 1.

- Sieveking, G. de G. 1954. Excavations at Gua Cha, Kelantan, 1954 (Part 1). FMJ I and II:75–138.

- Solheim II, W. G.

- 1959. Further notes on the Kalanay pottery complex in the Philippines. AP 3 (2): 157–166.

- 1964. The Archaeology of Central Philippines: A Study Chiefly of the Iron Age and its Relationships. Manila: Monograph of the National Institute of Science and Technology No. 10.

- 1968. The Batungan Cave sites, Masbate, Philippines, in Anthropology at the Eight Pacific Science Congress: 21–62, ed. W. G. Solheim II. Honolulu: Asian and Pacific Archaeology Series No. 2, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii.

- 1970a. Prehistoric archaeology in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia and the Philippines. AP 13:47–58.

- 1970b. Northern Thailand, Southeast Asia, and world prehistory. AP 13:145–162.

- Tăng Dực Đào (1994). On the struggle for democracy in Vietnam.

- Tucker, Spencer C. Oxford Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (hardback edition).

- Vuong Quan Hoang and Tran Tri Dung. The Cultural Dimensions of the Vietnamese Private Entrepreneurship, The IUP J. Entrepreneurship Development, Vol. VI, No. 3&4, 2009.

- Zinoman, Peter (2001). The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520224124.

Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190053796.

External links

[edit]- "Đồ đồng cổ Đông Sơn" [Đông Sơn ancient bronze tools] (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- "Ánh sáng mới trên một quá khứ lãng quên" [New Light on a Forgotten Past] (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2012-09-13.

- Vương, Liêm (27 March 2011). "Rediscovering the people's ethnic origins and ancestral lands during the Hùng kings' time". www.newvietart.com (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 1 April 2011.

- Hồng Bàng dynasty

- Ancient Vietnam

- States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC

- 258 BC

- 3rd-century BC disestablishments

- 1st-millennium BC disestablishments in Vietnam

- Former countries in Vietnamese history

- 29th-century BC establishments

- States and territories disestablished in the 3rd century BC