National Gallery of Australia

| |

Image taken from the south-west | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

Former name | Australian National Gallery |

|---|---|

| Established | 1967 |

| Location | Parkes, Canberra, Australia |

| Coordinates | 35°18′1.4″S 149°8′12.5″E / 35.300389°S 149.136806°E |

| Type | Art gallery |

| Director | Nick Mitzevich |

| Architect | Colin Madigan |

| Owner | Australian Government |

| Public transit access | ACTION buses (R2 & R6) |

| Website | nga |

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA), formerly the Australian National Gallery, is the national art museum of Australia as well as one of the largest art museums in Australia, holding more than 166,000 works of art. Located in Canberra in the Australian Capital Territory, it was established in 1967 by the Australian Government as a national public art museum. As of 2022[update] it is under the directorship of Nick Mitzevich.

Establishment

[edit]Prominent Australian artist Tom Roberts had lobbied various Australian prime ministers, starting with the first, Edmund Barton. Prime Minister Andrew Fisher accepted the idea in 1910, and the following year Parliament established a bipartisan committee of six political leaders—the Historic Memorials Committee. The Committee decided that the government should collect portraits of Australian governors-general, parliamentary leaders and the principal "fathers" of federation to be painted by Australian artists. This led to the establishment of what became known as the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, which was responsible for art acquisitions until 1973. Nevertheless, the Parliamentary Library Committee also collected paintings for the Australian collections of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Library, including landscapes, notably the acquisition of Tom Roberts' Allegro con brio, Bourke St West in 1918. Prior to the opening of the Gallery these paintings were displayed around Parliament House, in Commonwealth offices, including diplomatic missions overseas, and State Galleries.

From 1912, the building of a permanent building to house the collection in Canberra was the major priority of the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board. However, this period included two World Wars and a Depression and governments always considered they had more pressing priorities, including building the initial infrastructure of Canberra and Old Parliament House in the 1920s and the rapid expansion of Canberra and the building of government offices, Lake Burley Griffin and the National Library of Australia in the 1950s and early 1960s. In 1965 the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board was finally able to persuade Prime Minister Robert Menzies to take the steps necessary to establish the gallery.[1] On 1 November 1967, Prime Minister Harold Holt formally announced that the Government would construct the building.

Location

[edit]The design of the building was complicated by the difficulty in finalising its location, which was affected by the layout of the Parliamentary Triangle. The main problem was the final site of the new Parliament House. In Canberra's original Griffin 1912 plan, Parliament House was to be built on Camp Hill, between Capital Hill and the Provisional Parliament House and a Capitol was to be built on top of Capital Hill. He envisaged the Capitol to be "either a general administration structure for popular receptions and ceremony or for housing archives and commemorating Australian Achievements".[2] In the early 1960s, the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) proposed, in accordance with the 1958 and 1964 Holford plans for the Parliamentary Triangle, that the site for the new Parliament House be moved to the shore of Lake Burley Griffin, with a vast National Place, to be built on its south side, to be surrounded by a large mass of buildings. The Gallery would be built on Capital Hill, along with other national cultural institutions.[3]

In 1968, Colin Madigan of Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Partners won the competition for the design, even though no design could be finalised, as the final site was now in doubt. Prime Minister John Gorton stated that,

- "The Competition had as its aim not a final design for the building but rather the selection of a vigorous and imaginative architect who would then be commissioned to submit the actual design of the Gallery."[4]

Gorton proposed to Parliament in 1968 that it endorse Holford's lakeside site for the new Parliament House, but it refused and sites at Camp Hill and Capital Hill were then investigated. As a result, the Government decided that the Gallery could not be built on Capital Hill.[5] In 1971, the Government selected a 17-hectare (42-acre) site on the eastern side of the proposed National Place, between King Edward Terrace and for the Gallery. Even though it was now unlikely that the lakeside Parliament House would proceed, a raised National Place (to hide parking stations) surrounded by national institutions and government offices was still planned.[6] Madigan's brief included the Gallery, a building for the High Court of Australia and the precinct around them, linking to the raised National Place at the centre of the Land Axis of the Parliamentary Triangle, which then led to the National Library on the western side.

Development of the design

[edit]Madigan's final design was based on a brief prepared by the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) with input from James Johnson Sweeney and James Mollison. Sweeney was director of the Guggenheim Museum between 1952–1960 and director of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and had been appointed as a consultant to advise on issues concerning the display and storage of art. Mollison said in 1989 that "the size and form of the building had been determined between Colin Madigan and J.J. Sweeney, and the National Capital Development Commission. I was not able to alter the appearance of the interior or exterior in any way...It's a very difficult building in which to make art look more important than the space in which you put the art".[7] The construction of the building commenced in 1973, with the unveiling of a plaque by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. Construction was managed by P.D.C. Constructions under the supervision of the National Capital Development Commission and it was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1982, during the premiership of Whitlam's successor, Malcolm Fraser. The building cost $82 million.

In 1975, the NCDC abandoned the plan for the National Place, leaving the precinct five metres above the natural ground level, without the previously proposed connections to national institutions [8] and next to a vast space only partially taken up by Reconciliation Place, which does not substitute for the grand mass of buildings originally envisaged.

Appointment of an acting director

[edit]The Commonwealth Art Advisory Board recommended that Laurie Thomas, a former director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia and of the Queensland Art Gallery be appointed director, but the Prime Minister John Gorton took no action on this recommendation, as he apparently favoured the appointment of James Johnson Sweeney, although he was already 70.

James Mollison was exhibitions officer in the Prime Minister's Department from 1969 and the Government's failure to appoint a director of the National Gallery of Australia required Mollison to become involved in the development of the design for the building with the architects led by Colin Madigan. In November 1970, the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board recommended that he should be re-designated as assistant director (development). In May 1971, following Gorton's fall from power, the Government endorsed Madigan's sketches for the building. The new prime minister, William McMahon announced the appointment of Mollison as acting director of the National Gallery of Australia in October 1971. Tenders for construction were called in November 1972, just before the McMahon government's defeat in the December 1972 election.[9]

Building and garden

[edit]

The National Gallery building is in the late 20th-century Brutalist style. It is characterised by angular masses and raw concrete surfaces and is surrounded by a series of sculpture gardens planted with Australian native plants and trees.

The geometry of the building is based on a triangle, most obviously manifested for visitors in the coffered ceiling grids and tiles of the principal floor. Madigan said of this device that it was "the intention of the architectural concept to implant into the grammar of the design a sense of freedom so that the building could be submitted to change and variety but would always express its true purpose". This geometry flows throughout the building, and is reflected in the triangular stair towers, columns and building elements.

The building is principally constructed of reinforced bush hammered concrete, which was also originally the interior wall surface. More recently, the interior walls have been covered with painted wood, to allow for increased flexibility in the display of artworks.

The building has 23,000 m2 of floor space. The design provides space for both the display and storage of works of art and to accommodate the curatorial and support staff of the Gallery. Madigan's design is based on Sweeney's recommendation that there should be a spiral plan, with a succession of galleries to display works of art of differing sizes and to allow flexibility in the way in which they were to be exhibited.

There are three levels of galleries. On the principal floor, the galleries are large, and are used to display the Indigenous Australian and International (meaning European and American) collections. The bottom level also contains a series of large galleries, originally intended to house sculpture, but now used to display the Asian art collection. The topmost level contains a series of smaller, more intimate galleries, which are now used to display the Gallery's collection of Australian art. Sweeney had recommended that sources of natural light should not detract from the collections, and so light sources are intended to be indirect.

The High Court and National Gallery Precinct were added to the Australian National Heritage List in November 2007.[10]

Later extensions

[edit]The Gallery has been extended twice, the first of which was the building of new temporary exhibition galleries on the eastern side of the building in 1997, to house large-scale temporary exhibitions, which was designed by Andrew Andersons of PTW Architects. This extension includes a sculptural garden, designed by Fiona Hall. The 2006 enhancement project and new entrance was complemented by a large Australian Garden designed by Adrian McGregor of McGregor Coxall Landscape Architecture and Urban Design.

There have also been proposals, during the tenure of Director Brian Kennedy, for the construction of a new "front" entrance, facing King Edward Terrace. Madigan made known his concerns about these proposals and their interference with his moral rights as the architect and also expressed concerns about these changes.[11] A former director, Betty Churcher, was particularly critical of Madigan, and told a journalist that "the dead hand of an architect cannot stay clamped on a building forever".[12] When Ron Radford became director, he expanded the brief to include a suite of new galleries to display the collection of indigenous art and a new Australian Garden fronting King Edward Terrace.

The Minister for the Arts and Sport, Senator Rod Kemp, announced on 13 December 2006 that the Australian Government would provide $92.9 million for a major building enhancement project at the National Gallery of Australia, including around $20 million for previously approved building refurbishments. The building enhancements were designed to create new arrival and entrance facilities to improve public access to the Gallery's building and significantly increase display space, particularly for the collection of Australian Indigenous art.[13] Stage 1 of the Indigenous galleries and new entrance project was officially opened on 30 September 2010 by Quentin Bryce, Governor-General of Australia.[14] According to well-known architecture critic Elizabeth Farrelly, the new extension had three main tasks: "how to dock amicably with the existing architecture; how to provide the resulting whole with a new street "address"; how to create a logical, legible and deferential hanging space for the collection."[15]

Sculpture garden renewal and Ouroboros

[edit]

A project for the renewal of the sculpture garden was under way as of 2021. As part of the project, in September 2021 the gallery under director Nick Mitzevich commissioned a huge sculpture by Lindy Lee, 4 m (13 ft) high and based on the ouroboros (an ancient symbol depicting a snake eating its own tail), to be placed near its main entrance of the gallery. Unveiled in October 2024, the sculpture is the NGA's most expensive commission to date.[16][17] Two art critics criticised the purchase in 2021: John McDonald of The Sydney Morning Herald thought that the money could have been better spent filling some significant gaps in its collection,[18] while Christopher Allen concurred, and thought that it merely "offer[s] a passive experience to audiences who are unwilling or unable to engage more actively with works of art"[19] and that "$14m is an absurd price for a work of debatable value by an artist of modest standing".[20]

Directorship

[edit]In 1976, the newly established ANG Council advertised for a permanent director to fill the position that James Mollison had been acting in since 1971. The new prime minister Malcolm Fraser announced the appointment of Mollison as director in 1977.

James Mollison

[edit]James Mollison is notable for establishing the Gallery and building on the collection that had already been assembled of mainly Australian paintings by purchasing icons of modern western art, the best known were the 1974 purchases of Blue Poles by Jackson Pollock ($1.3m), and Woman V by Willem de Kooning ($650,000). These purchases were very controversial at the time, but are now generally considered to be visionary acquisitions.

He also built up the other collections, often with the help of donations. Starting in 1973 Mollison secured funding from Philip Morris to acquire contemporary Australian photography for the ANG, though Ian North was not appointed Foundation Curator of Photography until 1980.[21][22][23] In 1975, Arthur Boyd presented several thousand of his works to the Gallery. In 1977 Mollison persuaded Sunday Reed to donate Sidney Nolan's remarkable Ned Kelly series to the ANG. Nolan had long disputed Reed's ownership of these paintings, but the donation resolved their dispute.[24] In 1981, Albert Tucker and his wife presented a substantial collection of Tucker's collection to the Gallery. As a result of these and more recent donation, it has the finest collection of Australian art in existence.

He also arranged many touring exhibitions, most famously The Great Impressionist Exhibition of 1984.

His successor, Betty Churcher has said that when she took over in 1990, he "was of almost legendary stature [and] had single-handedly built a great and comprehensive collection from the ground up; indeed he had presided over the collection for more than twenty years with great flair, and over the institution for seven years — it was in the truest sense, his Gallery, his professional achievement."[25]

Betty Churcher

[edit]Betty Churcher became director in 1990. She had been formerly director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia. While director of the National Gallery, she was dubbed "Betty Blockbuster" because of her love of blockbuster exhibitions.

Churcher initiated the building of new galleries on the eastern side of the building, opened in March 1998, to house large-scale temporary exhibitions. It was under her directorship that the name of the Gallery was changed from the Australian National Gallery to its current title.

During her period, the Gallery purchased, among many other artworks, Golden Summer, Eaglemont by Arthur Streeton for $3.5 million. This was the last great Heidelberg School painting still in private hands.[26]

Brian Kennedy

[edit]Brian Kennedy was appointed director in 1997. He expanded the traveling exhibitions and loans program throughout Australia, arranged for several major shows of Australian art abroad, increased the number of exhibitions at the museum itself and oversaw the development of an extensive multi-media site. On the other hand, he discontinued the emphasis of his predecessor, Churcher, of showing blockbuster exhibitions.

During his directorship, the National Gallery of Australia gained government support for improving the building and significant private donations and corporate sponsorship. Private funding supported his notable acquisitions of David Hockney's A Bigger Grand Canyon for $4.6 million in 1999, Lucian Freud's After Cézanne for $7.4 million in 2001 and Pregnant Woman by Ron Mueck for $800,000.

He also introduced free admission to the gallery, except to major exhibitions. He campaigned for the construction of a new front entrance to the Gallery, facing King Edward Terrace, but this did not come to pass during his tenure.

Kennedy's cancellation of the Sensation exhibition (scheduled at the National Gallery of Australia from 2 June 2000 to 13 August 2000) was controversial, as it was seen by many as censorship. This exhibition was created by the Young British Artists of the Saatchi Gallery. Its most controversial work was Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary, a painting which used elephant dung and was accused of being blasphemous. The then Mayor of New York, Rudolph Giuliani campaigned against the exhibition, claiming it was "Catholic-bashing" and an "aggressive vicious, disgusting attack on religion." In November 1999, Kennedy cancelled the exhibition and stated that the events in New York had "obscured discussion of the artistic merit of the works of art."[27]

Kennedy was also repeatedly under attack over allegations that the air-conditioning was exposing its staff to cancer. Despite his denials that there was any problem with the air-conditioning, claims that the issue had been 'swept under the carpet' persisted. The air-conditioning was finally renovated in 2003.[28] Kennedy announced that he would not seek extension of his contract in 2002. He has denied that he was under any government pressure to do so.

Ron Radford

[edit]Ron Radford was appointed director in late 2004. He was formerly director of the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Radford has lent out the Gallery's old masters collection (European art, prior to the 19th century) for long-term display to state galleries, noting that he "considers the collection of less than 30 paintings, put together by Mollison to give context to the modern collection, as too small to make any impact on the public". He has been quoted as saying that the gallery should concentrate on its strengths – European art of the first half of the 20th century, 20th-century American art, photography, Asian art and the 20th-century drawing collection, and to fill the gaps in the Australian collection.[29]

In September 2005, there was considerable publicity about an offer to the gallery of Sketch for Deluge II by Wassily Kandinsky for $35 million. The gallery did not subsequently go through with the purchase.

Radford has been notable in securing funding and completing the building of the new entrance to the Gallery as well as an extension for Indigenous galleries, public and function areas. In developing the collection he has been notable for a series of acquisitions of indigenous art, in particular the largest collection of watercolours by Albert Namatjira and the James Turrell sculpture and installation Within without (2010).

Gerard Vaughan

[edit]In October 2014, it was announced that Gerard Vaughan would be the new director of the National Gallery of Australia from 10 November. He was formerly director of the National Gallery of Victoria from 1999 to 2012.[30]

In 2014, the gallery sued antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor in New York Supreme Court for allegedly hiding evidence that an 11th-century sculpture of Shiva Nataraja known as the Sripuranthan Natarajan Idol, bought by the gallery for A$5.6 million in 2008, had been stolen from an Indian temple in Tamil Nadu.[31] The National Gallery voluntarily removed a bronze statue of the Dancing Shiva from display, as the Indian government formally requested the statue's return.[32]

Nick Mitzevich

[edit]In April 2018, it was announced that Nick Mitzevich, the third NGA director to be appointed from the Art Gallery of South Australia, would take over at the start of July 2018.[33][34] His term at the NGA has encountered several challenges: in January 2020 the gallery had to be shut because of smoke from bushfires and then again after a hailstorm. A couple of months later, the Covid pandemic struck, leading to a closure of over 70 days. In January 2021, Mitzevich had plans to re-hang the permanent collection, swapping the location of international art with that of Australian art.[35]

Exhibitions and initiatives

[edit]Women Hold Up Half The Sky

[edit]Women Hold Up Half The Sky was a large exhibition held in March to April 1995, to celebrate International Women's Day.[36] Named after Adelaide artist Ann Newmarch's famous print of the same name included in the exhibition, the exhibition was curated by Roger Butler. It was opened by Carmen Lawrence,[37] and also included a travelling exhibition called Sydney by Design.[38] The exhibition was part of the national commemoration of the UN's International Women's Year, and the accompanying book, The National Women's Art Book, was edited by Joan Kerr.[37][39][40]

Comprising around 300 works from the gallery's own collection, the exhibition included the work of Agnes Goodsir, Bessie Davidson, Clarice Beckett, Olive Cotton, Grace Cossington Smith, Yvonne Audette, Janet Dawson, Lesley Dumbrell, Margaret Worth, Rosalie Gascoigne, Bea Maddock, Judy Watson,[37] Frances Burke, Margaret Preston,[36] Olive Ashworth, and other artists of the previous 150 years.[41]

The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters story 1937-1997

[edit]The exhibition The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters story 1937-1997 was a major exhibition of the work of more than 100 Aboriginal artists held in 1997,[42] curated by Nigel Lendon and Tim Bonyhady.[43] The artists were Yolngu painters from Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, including senior member of the Rirratjingu clan Mawalan Marika[44] as well as Ramingining artist Philip Gudthaykudthay (aka "Pussycat").[45][46] The artworks all related to the story of ancestral creator beings of Arnhem Land known as the Wagilag sisters.[44]

National Indigenous Art Triennial

[edit]The NGA held the inaugural National Indigenous Art Triennial (NIAT), Culture Warriors, from 13 October 2007 to 10 February 2008. The guest curator was Brenda L Croft, Senior Curator, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art. The exhibition was the largest survey show of Indigenous art at the NGA in over 15 years, and featured works by selected artists created during the previous three years.[47] A free exhibition, it featured artists from every state and territory.[48]

The 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial, unDISCLOSED, ran from May to July 2012 and featured 20 Indigenous artists, including Vernon Ah Kee, Julie Gough, Alick Tipoti, Christian Thompson, Lena Yarinkura, Michael Cook and Nyapanyapa Yunupingu. The theme alludes to "the spoken and the unspoken, the known and the unknown, what can be revealed and what cannot". The exhibition afterwards toured the country, shown at Cairns Regional Gallery, the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide and the Western Plains Cultural Centre in Dubbo, NSW.[49]

The 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial, Defying Empire, was held from 26 May to 10 September 2017, curated by Tina Baum, NGA Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art. The title references the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum, that recognised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as Australians for the first time.[50]

The 4th Triennial Ceremony, takes place from 26 March to 31 July 2022. It explores the idea of ceremony, and is curated by Hetti Perkins.[51]

Balnaves Contemporary Series

[edit]In 2018 the Balnaves Contemporary Intervention Series was launched, delivered in partnership with the Balnaves Foundation.[52][53] The platform, later renamed to Balnaves Contemporary Series, commissions artists to create new work. Artists commissioned by this project include Jess Johnson and Simon Ward (2018); Sarah Contos (2018); Patricia Piccinini (Skywhales, 2020–21); Judy Watson and Helen Johnson; and Daniel Crooks (2022).[54]

Know My Name

[edit]

Know My Name is "an initiative of the National Gallery of Australia to celebrate the significant contributions of Australian women artists". Launched in 2019, after it was discovered that only 25 per cent of the gallery's collection was made by women through information from the Countess Report.[55][56] This exhibition features exhibitions, events, commissions, creative collaborations, publications and partnerships that highlight the talent and work of women artists. As part of the program, the NGA also instigated a new set of principles to ensure gender parity in the organisation, programming and collections.[57]

The exhibition Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now: Part One, held from 14 Nov 2020 to 9 May 2021, featured art made by women, drawn from the NGA's own collection as well as other institutions around Australia.[58] Featured artists included Margaret Olley, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Tracey Moffatt, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Mabel Juli, Rosemary Laing, Grace Cossington Smith, Thea Proctor, Betty Muffler,[59] Stella Bowen, Dora Chapman, Fiona Foley, Brenda L. Croft,[56] Discount Universe and many others.[60] A book entitled Know My Name was published to accompany the exhibition in 2020.[61] A four-day conference was held to coincide with the exhibition's opening.[62]

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now: Part Two was opened on 12 June 2021 and finishes on 26 June 2022. The two exhibitions do not purport to be a complete account, but rather "[look] at moments in which women created new forms of art and cultural commentary such as feminism... [highlighting] creative and intellectual relationships between artists across time".[63]

Body Sculpture

[edit]In 2020 the gallery purchased American artist Jordan Wolfson's "Cube"[64] for A$6.67 million,[65] about half the museum's annual acquisition budget. The final transport and installation of the work was then delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic;[64][66] it was finally unveiled in 2023.[65] Renamed Body Sculpture, the robotic artwork is the first solo presentation of Wolfson's work in Australia, and a world premiere of the work, which is on display alongside key works from the national collection selected by the artist from 9 December 2023 until 28 July 2024.[67]

Other exhibitions

[edit]- The Great Impressionist Exhibition (1984)

- Ken Tyler: Printer Extraordinary (1985)

- Angry Penguins and Realist Painting in Melbourne in the 1940s (1988)

- Under a Southern Sun (1988–89)

- Australian Decorative Arts, 1788–1900 (1988–89)

- Word as Image: 20th Century International Prints and Illustrated Books (1989)

- Rubens and the Italian Renaissance (1992)

- The Age of Angkor: Treasures from the National Museum of Cambodia (1992)

- Surrealism: Revolution by Night (1993)

- 1968 (1995)

- Turner (1996)

- Rembrandt: A Genius and his Impact (1997–98)

- New Worlds from Old: 19th Century Australian and American Landscapes (1998)

- An Impressionist Legacy: Monet to Moore, The Millennium Gift of Sara Lee Corporation (1999)

- Monet & Japan (2001)

- William Robinson: A Retrospective (2001–02)

- Rodin: A Magnificent Obsession, Sculpture and Drawings (2001–02)

- Margaret Preston, Australian Printmaker (2004–05)

- No Ordinary Place: The Art of David Malangi (2004)

- The Edwardians: Secrets and Desires (2004)

- Bill Viola: The Passions (2005)

- James Gleeson: Beyond the Screen of Sight (2005)

- Constable: Impressions of Land, Sea and Sky (2005)

- Imants Tillers: Inventing Postmodern Appropriation (2006) [68]

- George W. Lambert Retrospective: Heroes & Icons (2007) [69]

- Turner to Monet: The Triumph of Landscape (2008)

- Degas: Master of French Art (2009)

- McCubbin: Last Impressions 1907–1917 (2009)

- Masterpieces from Paris (2010), on loan from Musée d'Orsay.

- Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume (2011)

- Renaissance: 15th & 16th Century Italian Paintings from the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (2011–2012)

- Toulouse-Lautrec - Paris & the Moulin Rouge (2012–2013)

- Jeffrey Smart (2021–2022)[70][71]

NGA Youth Council

[edit]The National Gallery Youth Council is a group of young creatives recruited from across the country who represent and advocate for young people at the gallery. The group, aged between 15 and 25, meet online monthly and work with staff and artists to develop and deliver a variety of programs for young people.[72]

Collection

[edit]

The collection of the National Gallery of Australia held more than 166,000 works of art as of 2012.[73] and includes:

- Australian art

- Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art (mostly recent, but in traditional forms)

- Art in the European Tradition (from European settlement to the present day)

- Western art (from Medieval to Modern, mostly Modern)

- Eastern art (from South and East Asia, mostly traditional)

- Modern Art (international)

- Pacific Arts (from Melanesia and Polynesia mostly traditional)

- Photography (International & Australian)

- Crafts (dishes to dresses, international)

- Sculpture garden (Auguste Rodin to Modern)

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art

[edit]

This collection is dominated by the Aboriginal Memorial of 200 painted tree trunks commemorating all the indigenous people who had died between 1788 and 1988 defending their land against invaders. Each tree trunk is a dupun or log coffin, which is used to mark the safe tradition of the soul of the deceased from this world to the next. Artists from Ramingining painted it to mark the Australian Bicentenary and it was accepted for display by the Biennale of Sydney in 1988. Mollison agreed to purchase it for permanent display before its completion.[74]

Australian art (non-Indigenous)

[edit]

This includes works by:

- John Glover – Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point

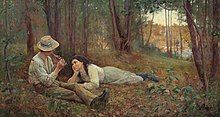

- Frederick McCubbin – Afterglow, Bush Idyll (on long term loan from private collection)

- Tom Roberts – Going Home, Storm Clouds, In a corner on the Macintyre, An Australian Native, The Sculptor's Studio

- Arthur Streeton – From McMahons Point – Fare 1 Penny, The Selector's Hut, Golden Summer, Spirit of the Drought

- Charles Conder – The Yarra, Heidelberg, Bronte Beach, Under a Southern Sun

- Margaret Preston – Flying over the Shoalhaven River, Flapper

- Grace Cossington Smith – Interior in Yellow

- Lloyd Rees – A South Coast Road

- William Dobell – The Red Lady

- Albert Tucker – Pick up, Images of modern evil (collection), Victory Girls

- Russell Drysdale – The Drover's Wife, The Rabbiter and his Family

- Sidney Nolan – Ned Kelly, The Slip, The Burning Tree, Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly, Stringybark Creek, The Chase, Kelly Crossing the Bridge (and many other Ned Kelly paintings), Kiata, Head of a Soldier

- Arthur Boyd – The Mining Town, Boat Builders, Eden

- Joy Hester – Nude in Hat, Mother and Child

- John Perceval – Boy with Cat

- Ron Mueck – Pregnant Woman

- Patricia Piccinini – The Skywhale

-

Eugene von Guerard, North-east view from the northern top of Mount Kosciusko, 1863

-

Frederick McCubbin, Violet and Gold, 1911

-

Hugh Ramsay, Portrait of Nellie Patterson, 1903

-

Violet Teague, The boy with the palette, 1911

-

Clarice Beckett, Sandringham Beach, 1933

Western art

[edit]

The focus of the Gallery's international collection is primarily on late 19th-century and 20th-century art [75] although not all artworks are on display. There is a strong collection of modern works. It includes works by:

- Paul Cézanne – L'Après-midi à Naples (Afternoon in Naples)

- Claude Monet – Haystacks, Midday and Water Lilies

- Fernand Léger – Trapeze Artists

- Pablo Picasso – A complete set of the Vollard Suite [76]

- Jackson Pollock – Blue Poles, Totem Lesson 2

- Willem de Kooning – Woman V

- Andy Warhol – Elvis, Electric Chair

- Mark Rothko – Multiform, Black, Brown on Maroon or Deep Red and Black

- Roy Lichtenstein – Kitchen Stove

- David Hockney – A Bigger Grand Canyon

- Lucian Freud – After Cézanne

- Henri Matisse – Oceania, the Sea, Oceania, the Sky

- Constantin Brâncuși – Bird in Space

- Albert Gleizes – Woman with Black Glove (Femme au gant noir)

- Paul Gauguin – The blue roof or Farm at Le Pouldu

-

Gustave Courbet, Study for Les Demoiselles des bords de la Seine, 1856

-

Paul Cézanne, L'Après-midi à Naples (Afternoon in Naples), 1875

-

Georges Seurat, Study for Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp, 1885

-

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Pearl (The Sands, Dieppe), 1885

-

André Derain, Self-portrait in studio, 1903

-

Kasimir Malevich, Stroyuschiysya dom (House under construction), 1915

The Gallery has a small collection of European Old Master paintings.

Eastern art

[edit]This includes:

Sculpture garden

[edit]

The sculpture garden includes works by:

- Bert Flugelman – Cones

- Antony Gormley – Angel of the North (life-size maquette)[78]

- Fujiko Nakaya – Fog sculpture, this only operates between noon and 2pm. It has been seen as a work of Gas sculpture.

- Henry Moore – Hill Arches

- Mark di Suvero – Ik Ook

- Auguste Rodin – The Burghers of Calais (1 of 12 sets)

- Aristide Maillol – La Montagne (The Mountain)

- Clement Meadmore – Virginia

- Barnett Newman – Broken Obelisk

See also

[edit]- Art of Australia

- Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Art Gallery of South Australia

- List of national galleries

- List of sculpture parks

- National Gallery of Australia Research Library

- National Gallery of Victoria

- National Portrait Gallery

References

[edit]- ^ Green, Pauleen, ed. (2003). Building the Collection. National Gallery of Australia. p. 408. ISBN 0-642-54202-3., pp2-9

- ^ Parliamentary Zone Development Plan. National Capital Development Commission. 1982. p. 125. ISBN 0-642-88974-0., p12

- ^ Parliamentary Zone Development Plan, pp20-1

- ^ Green: p. 339

- ^ Parliamentary Zone Development Plan, p23

- ^ Parliamentary Zone Development Plan, pp23-4

- ^ Green : pp. 379–80

- ^ "NGA and High Court – statement of significance". Royal Australian Institute of Architects. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- ^ Green : pp14-17

- ^ Australian National Heritage listing for the High Court-National Gallery Precinct

- ^ Lauren Martin (19 October 2005). "Gallery defiant over redesign". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (25 September 2006). "Designs on his landmark leave architect in distress". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Major expansion of the National Gallery of Australia" (Press release). Senator Rod Kemp. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2006.

- ^ "National Gallery of Australia". Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Farrelly, Elizabeth (9 October 2010). "Watch this space - Brutalism meets beauty in the National Gallery's new wing". The Sydney Morning Herald. "Spectrum" section. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Convery, Stephanie (23 September 2021). "National Gallery of Australia orders $14m Ouroboros sculpture – its most expensive commission so far". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Daniel Browning. "Public art, toppled monuments and the statue in the crate" (Audio + text). ABC Radio National (Interview). The Art Show. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ John McDonald (23 September 2021). "Is the National Gallery of Australia's new sculpture worth the $14m price tag?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Christopher Allen (24 September 2021). "Stupid NGA money reflects poor leadership". The Australian. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/visual-arts/christopher-allens-verdict-on-lindy-allens-ouroboros-an-absurd-price-for-a-work-of-debatable-value-by-an-artist-of-modest-standing/news-story/a55f9f9cebe09f92b4c1e299402af638?amp

- ^ Mollison, James (1979), Australian photographers: the Philip Morris Collection, Philip Morris (Australia)Ltd, ISBN 978-0-9500941-1-3

- ^ King, Natalie, ed. (2010), Up close: Carol Jerrems with Larry Clark, Nan Goldin and William Yang, Jerrems, Carol (photographer); Clark, Larry (photographer); Goldin, Nan (photographer); Yang, William (photographer), Schwartz City: Heide Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-1-86395-501-0

- ^ Palmer, Daniel (30 November 2016). "Ian North, Foundation Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia | Curating Photography". Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Burke, Janine (January 2004). The Heart Garden: Sunday Reed and Heide. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House. p. 552. ISBN 1-74051-202-2. p. 350.

- ^ Green: p175

- ^ Green: p174

- ^ Valerie M. Arvidson (2006). "A Curator from the Outback". Dartmouth Free Press. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- ^ "Passing on a 'poisoned chalice'". The Age. 14 February 2004. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- ^ "Radford to banish old masters from NGA". The Canberra Times. 12 April 2006. Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ^ Debbie Cuthbertson, "Gerard Vaughan named National Gallery of Australia director". Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014

- ^ News International: The Rest of the Stories That Mattered--At a Glance, The Art Newspaper, March 2014, p. 11.

- ^ "Dancing Shiva: National Gallery of Australia to return allegedly stolen statue to India". ABC. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Dingwell, Doug (9 April 2017). "Nick Mitzevich confirmed new boss for National Gallery". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "Dr Nick Mitzevich". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ McIlroy, Tom (28 January 2021). "Coronavirus Australia: NGA director Nick Mitzevich is ready to embrace controversy after a difficult year". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Women Hold Up Half the Sky". Woroni (Canberra, ACT : 1950 – 2007). 9 March 1995. p. 28. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Barron, Sonia (31 March 1995). "Affirming the role of women artists". The Canberra Times. Vol. 70, no. 21, 897. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. p. 13. Retrieved 7 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Women hold up half the sky :: event". Design and Art Australia Online. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Mighty book takes the cake". The Canberra Times. Vol. 70, no. 21, 879. Australian Capital Territory. 13 March 1995. p. 15. Retrieved 7 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Macklin, Wendy (10 March 1995). "Catching the bus at last". The Canberra Times. Vol. 70, no. 21, 876. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. p. 12. Retrieved 7 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Women Hold Up Half The Sky". Design & Art Online. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Caruana, Wally; Lendon, Nigel (1997). The Painters of the Wagilag sisters story, 1937-1997 / edited by Wally Caruana, Nigel Lendon. National Gallery of Australia. ISBN 064213068X. Excerpt

- ^ "Biographies". Rugs of War. 7 August 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Djang'kawu Ancestors, c.1964". Deutscher and Hackett. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Watson, Ken. "Philip Gudthaykudthay". Art Gallery of NSW. [From] Ken Watson in Tradition today: Indigenous art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Phillip Gudthaykudthay, b. 1935". National Portrait Gallery people. 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "National Indigenous Art Triennial '07:Culture Warriors". National Gallery of Australia - Home. 13 October 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Nona, Dennis (15 April 2020). "Exhibiting Indigenous art". reCollections. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "unDISCLOSED - About". National Gallery of Australia - Home. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Australia, National Gallery Of (10 September 2017). "Defying Empire". National Gallery of Australia - Home. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Bremer, Rudi (26 March 2022). "National Indigenous Art Triennial at National Gallery of Australia centres the ongoing process of ceremony in Aboriginal art". ABC News. Awaye!. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "The Balnaves Foundation supports new contemporary art series at NGA". Art Almanac. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Intervention art a new way to experience the National Gallery". OutInCanberra. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "The Balnaves Contemporary Series at the National Gallery". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Little, Elizabeth; Simpson, Lea (1 March 2023). "Counts Count: Collections Analysis and Gender Equity at the National Gallery of Australia Research Library and Archives". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. 42 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1086/728258. ISSN 0730-7187.

- ^ a b Burnside, Niki (13 November 2020). "Know My Name exhibition at National Gallery of Australia shines a spotlight on female artists". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Know My Name: Overview". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now: Part One". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Browning, Daniel (8 July 2021). "How APY artist Betty Muffler uses painting as a means to heal country". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Know My Name: National Art Event". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "The Book". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Know My Name Conference". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now: Part Two". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Controversial $6.8 million art acquisition delayed due to coronavirus". 24 April 2020.

- ^ a b Fortescue, Elizabeth (8 December 2023). "National Gallery of Australia finally unveils controversial £3.5m Jordan Wolfson commission". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Greenberger, Alex (9 March 2020). "Jordan Wolfson's Latest Provocation Has Already Been Acquired by the National Gallery of Australia". Artnet. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture". National Gallery of Australia. 9 December 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Imants Tillers". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "George.W.Lambert Retrospective". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ McDonald, John (10 December 2021). "The NGA has a hit on its hands with new Jeffrey Smart exhibition". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Fortescue, Elizabeth (7 December 2021). "Modern master's mural hidden in a Sydney bottle shop". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "National Gallery Youth Council". National Gallery of Australia. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Annual Report 2011-12" (PDF). National Gallery of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Green, pp. 199-204.

- ^ "Collections of the National Gallery of Australia". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 25 January 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jane Kinsman. "Vollard Suite". National Gallery of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Tang dynasty (618-907) China - Standing horse, 8th century". artsearch.nga.gov.au. National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Warden, Ian (25 December 2014). "Gang-gang: Ding dong puzzlingly on high". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Thomas, Daniel (2011). "Art museums in Australia: a personal account". Understanding Museums. - Includes link to PDF of the article "Art museums in Australia: a personal retrospect" (originally published in Journal of Art Historiography, No 4, June 2011).

External links

[edit]- Official website

- A virtual walk through National Gallery of Australia - 2015

- Kenneth Tyler Printmaking Collection Online at the National Gallery of Australia

- "Place ID 105745". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government.

- National Gallery of Australia on Artabase Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- National Gallery of Australia within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to National Gallery of Australia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to National Gallery of Australia at Wikimedia Commons

- National Gallery of Australia

- Commonwealth Government agencies of Australia

- Art museums and galleries in Canberra

- Brutalist architecture in Australia

- National museums of Australia

- Sculpture gardens, trails and parks in Australia

- 1982 establishments in Australia

- Buildings and structures completed in 1982

- Art museums and galleries established in 1982

- Outdoor sculptures in Canberra