Winfield Township, New Jersey

Winfield Township, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Welcome sign at the intersection of Stiles Street and Winfield Place | |

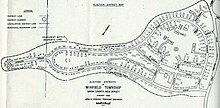

Map of Winfield Township in Union County. Inset: Location of Union County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. | |

Census Bureau map of Winfield Township, New Jersey. | |

Location in Union County Location in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40°38′06″N 74°17′23″W / 40.634885°N 74.289847°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Union |

| Incorporated | July 28, 1941[3][4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Township |

| • Body | Township Committee |

| • Mayor | Joseph P. Byrne (D, term ends December 31, 2024)[5] |

| • Municipal clerk | Melanie Slowik[6] |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.18 sq mi (0.47 km2) |

| • Land | 0.18 sq mi (0.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0.00% |

| • Rank | 560th of 565 in state 21st of 21 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 1,423 |

• Estimate (2023)[10] | 1,392 |

| • Rank | 516th of 565 in state 21st of 21 in county[11] |

| • Density | 7,855.0/sq mi (3,032.8/km2) |

| • Rank | 53rd of 565 in state 6th of 21 in county[11] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code | 908[13] |

| FIPS code | 3403981650[1][14][15] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0882215[1][16] |

| Website | www |

Winfield Township (also called Winfield Park) is a township in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the township's population was 1,423,[9] its lowest decennial census and a decrease of 48 (−3.3%) from the 2010 census count of 1,471,[17][18] which in turn reflected a decline of 43 (−2.8%) from the 1,514 counted in the 2000 census.[19] The township is the sixth-smallest municipality in the state.[20] Winfield and Linden share the same ZIP Code.

Winfield Township was incorporated as a township by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on August 6, 1941, from portions of Clark and Linden, passing over the Governor's veto.[3]

History

[edit]

The Winfield Park Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Project (Project No. 28071) is a 700-unit development of 254 buildings that were originally planned and developed by and built for the defense workers of the Kearny, New Jersey, shipyards. This was the last of eight projects undertaken by the Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Division of the Federal Works Agency under the leadership of Colonel Lawrence Westbrook. In earlier stages, Winfield Park was known as the Rahway River Park Project. John T. Rowland served as the project's architect.[21] Winfield Park is located almost immediately off of exit 136 of the Garden State Parkway; the municipalities of Cranford, Linden and Clark surround Winfield Township, a governmental entity established to enclose the Winfield Park Project. The Township is bordered on three sides by the Rahway River and Rahway River Park (which adds substantially to the park-like setting envisioned by the planners). Units range in size and type from single-family homes to two-story (plus basement) two- and three-bedroom apartments, better known today as Townhouses; to one-story (plus basement) two-bedroom apartments; and one-bedroom apartments, better known to residents as "bachelors." Within the town are located an elementary school, two-store shopping center and Senior Citizen Hall, Community Center, Mutual Housing Office, and Garage, Volunteer Fire and Ambulance Squad Building, and Municipal Building/Police Office.

The defense workers of the Kearny Shipyards had advocated early in 1940 for housing to be developed in the northern New Jersey area. These workers were early and vocal supporters of the National Housing for Defense Act of 1940, also known as the Lanham Act, and the mutual housing program. In January, 1941, a report on the housing requirements of the northern New Jersey area indicated that 1000 units were needed. The Defense Housing Coordinator approved the construction of a 300-unit project in the Newark/ Harrison area and a 700-unit project "to be built as a project itself sponsored by a responsible committee of the defense workers who will live in them." The housing committee had seven working policies that it had developed and that it wanted to apply to the workers' housing, all of which they believed conformed with the original intentions of the Lanham Act of 1940 ("The housing is to be wherever feasible of a permanent nature, and after the emergency has passed these homes are to be disposed of, and in that way the Government is to recoup the initial investment... and they will be available for permanent homes." The cost per unit was set at, and not permitted to exceed $3000.00.) and fit well within the mutual housing program.

1. Management of all community affairs, including relations with local government, should be in the hands of the residents of the new project.

2. Each unit should be assessable for its portion of local taxes, and every effort needs to be made "that both houses and householders should be easily and naturally assimilated into the normal scheme of the locality."

3. The Federal Works Agency (FWA) would provide all streets, sewers, parks, and all other facilities for the project.

4. All dwellings built for civilian defense workers should be sold as a group to local housing corporation as soon as they are completed.

5. All stockholders in the project are, and should be considered as, householders.

6. All management and operating procedures must be carried out under the direction of the local corporation, and not under the direction of the federal government.

7. Housing Corporation must enter into a contract of sale, rather than a rental agreement, with each householder.

Although the committee was completely convinced of the quality of the mutual ownership program itself, they did insist on improvements in the quality of the units over those that had been first designed and built for the Audubon Park project. They especially insisted on the construction of full basements for their new homes.[22]

Choosing the site

[edit]

The first major job that faced the development committee was finding and selecting a suitable site for a 700-unit housing project in northern New Jersey. The United States Housing Authority provided two site selection experts, and the New Jersey State Planning Commission assisted in the site selection process. The final location had to be relatively inexpensive to purchase, near major utility networks for water, gas, electric, and sewer connections, and be in a financially stable host community with underutilized public facilities and services. Major urban areas in northern New Jersey were eliminated early because no plots of land were large enough for the project. The marshy rural areas near the shipyards were also found unacceptable early on. Quickly the committee began focusing its attention on the surrounding suburban communities, which were very popular among its work constituency. Suburban communities lacked financial stability because they lacked the industrial base necessary to keep residential property taxes low. The people of these prospective host communities were also frightened that the new project would be a direct liability rather than an asset for their towns.

Early resistance from potential host communities over financial impact concerns meant that the committee had two choices: to stop the project and wait for the problems to be resolved or push ahead, utilizing the powers granted in the Lanham Act powers to overrule local resistance, but creating a great deal of friction that could potentially affect the project's future success. The housing need was so great, though, that the only viable choice was the second one, and they pushed forward to find a site. Consciously attempting to avoid conflict, the committee tried to assure potential host communities that projects built within the mutual ownership program would pay real taxes and not make payments in place of taxes as outlined in the Lanham Act of 1940. They also petitioned the United States Congress to provide additional funds to host communities that would allow them to expand public services and facilities without imposing additional local taxes. But the financial concerns of the residents only served to exacerbate other local fears about the new project. Many defense workers took these other fears very personally.

"Realizing that such an influx of families would engulf them (host community) in a tidal wave of financial difficulty, the municipal government of the various towns considered, stirred up a tremendous opposition to the project and the people to live in it with untrue and unjust charges such as decreased realty values, 'tax exempt properties,' 'lower class of people,' and so forth, which are all obviously false. We are a class of people who are gainfully employed, we are law abiding, decent, and respectable, and we are Americans."

Seven potential host communities were eventually identified and researched. The committee named Union Township, New Jersey as their final choice, but under intense community and [political pressure] this decision was reversed, and Clark, New Jersey was selected as the final site of the project. Colonel Lawrence Westbrook, Special Assistant in the Federal Works Agency with responsibility for the Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Division, wrote the following letter to Union Township opponents of the project, clearly showing his frustration.

"Your letter to Congressmen McLean protesting the location of a proposed defense housing project in Union Township has been referred to this office. This is to advise you that a decision has been made to locate the project in Clark Township. It is desired to make it entirely clear, however, that in reaching this decision this office in no manner agrees that the numerous protests received from various persons and organizations in Union Township were based upon valid premises. We feel certain that if you and the other protesters had been acquainted with all of the facts in the situation, you would not have filed your protest. On the contrary, it is believed that you would have urged the Government to locate the project in your township. Since the project will be undertaken in your immediate neighborhood, you will have ample opportunity to determine whether or not the disadvantages to the community, as claimed by your Mayor, were based upon sound facts."

Clark Township's municipal government had been very desirous of the siting of the project in their township. It had extended an invitation to the Federal Works Agency after the Union Township protests had erupted. However, the reaction of Clark's residents to the project indicates that the Township Committee did not have a good understanding of the actual desires of their constituents.[23]

Clark Township protests

[edit]The residents of Clark—in 1940, a rural community of 350 homes and 1,250 registered voters—were first informed of their municipality's selection as the final site of the 700-unit mutual housing project at a town meeting on April 1, 1941. During the meeting, a letter from John Carmody, Federal Works Administrator, was read to the residents, in which he said:

"I am glad to say that a decision has been reached to construct this project in your township, and I want to take this occasion to thank you and your associates on the Township Committee for your intelligent and patriotic attitude."

But the residents of Clark were not moved by Mr. Carmody's supportive words. One local paper reported that

"Joseph Aaron, who came up from his winter home in Florida to attend the session, demanded the ousting of the Township Committee. Several spirited sallies of this type marked the meeting, the largest gathering of its kind ever held in the township."

The residents of the Township demanded that they be provided with answers to the following questions:

1. Why was the siting of the project in the Township handled so secretly?

2. What guarantees could be given that this project would be permanent in nature?

3. Would Clark have to pick up the cost of maintaining the project after the emergency ends?

4. Who would pay for new schools, equipment, streets, sewers, fire and police protection?

5. Would the Federal Works Agency guarantee in writing that the project will never become a burden to Clark?

Federal Works Agency Special Counsel Colvin, rather than trying to calm the residents' fears, reminded one and all that the FWA had been empowered by Lanham Act to place a defense housing project anywhere it deemed necessary appropriate, without discussions with residents. During his remarks, he made only brief mention of new public works being provided by the Federal Works Agency, or Title II of the Lanham Act (then being discussed in the US Congress to provide $150 million for the construction and provision of public services and facilities in host communities of defense housing projects). A worker from the Kearny Shipyards also spoke and assured the residents that their new neighbors would be "good people" and that employment at the yards would be stable for at least the "next 10 to 15 years". Not satisfied by any of this information and feeling betrayed by their own leaders, the residents demanded that an immediate vote be taken against the project. This request was denied. In response, the residents announced the formation of an opposition group, headed by Mr. Arthur de Laski, with the stated goals of seeking the impeachment of all municipal officials and stopping the mutual housing project.[24]

The residents of Clark opposed to Winfield, believed that its sitting within their community would double local taxes. Opposition leaders created elaborate models to show how the additional needs for general services, election, fire and police protection, streets, lighting, water, sanitation, and school costs would quickly double the municipal budget from a yearly total of $33,929 to $66,563. The residents also expressed concern that the project would add approximately 1500 new registered voters to the community: original residents would now be substantially outnumbered in local elections. Additionally, local real estate interests were fearful that the project would flood the local housing market, severely deflating prices after the emergency because of postwar abandonment. Most planned units would not be single-family homes, which many believed would lead to a less stable community and a deterioration of the real estate market. The Union County Parks Department expressed concern about the construction of Winfield— Rahway River Park surrounded the project on three sides—since their own planning program had called for the development of this particularly desirable tract of land with expensive single family homes. The residents continued to be concerned that their new neighbors would be of a lower class of people (although they had been promised that they would be primarily middle-class and would all be white thanks to housing officials not permitting racial integration in most public housing projects of the time),[25] and were annoyed these potential new neighbors would be getting subsidies at their expense.[26]

Lawrence Westbrook believed that Charles Palmer, the Defense Housing Coordinator, had encouraged and supported the formation of the Clark Township opposition group to accomplish his own hidden agenda of centralizing control over the Defense Housing initiative in his hands. Westbrook testified before Congress that Palmer's brother-in-law, who lived in northern New Jersey, had secretly led a delegation from Clark to visit Palmer and discuss their concerns about the construction of Winfield Park. Westbrook believed that Palmer, during this meeting, had provided this group with information and advice on how to successfully fight the project.[27]

By late May 1941, the Clark opposition group had successfully organized in advance of municipal elections and replaced all township leaders responsible for bringing the Winfield Park project to Clark. Attention now turned to stop the mutual housing project, or at least transferring most of its costs and impact to someone else. Opposition leaders carefully studied the publicity surrounding the earlier construction of the Audubon Park Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Project just outside Camden, New Jersey. The community, in that case, had followed an unsuccessful attempt to stop the project with building codes and local ordinances. All of these attempted blocks to construction were overturned by courts sympathetic to the powers given to the [FWA] by the Lanham Act. The Clark opposition developed a new and innovative opposition strategy. They would attempt to have the entire Winfield Park Mutual Housing project declared as a separate municipality by the New Jersey State Legislature. As a separate municipality, all costs for public services and facilities would be the responsibility of the residents of Winfield Park and not the residents of Clark. With Winfield Park Township established as a separate municipality, opponents believed the project would be killed because the federal government and potential residents would shy away from the overwhelming expenses and confusing legalities of this new governmental structure. Immediately Westbrook and other project supporters reacted to this strategy by declaring that the opposition was attempting the sabotage the entire national defense program. In defiance, Westbrook declared that he was sure the project would not only survive this attack but would outlive its surrounding communities.[28]

The creation of Winfield Township

[edit]

On June 30, 1941—six days after the construction of Winfield Park had begun—Union County Assemblyman Pascoe presented a bill to the New Jersey General Assembly establishing Winfield Township, New Jersey (originally, the bill called for the establishment of Lindark, New Jersey). After presenting the bill, Pascoe asked for and received a suspension of the rules so that the vote on the bill could follow its first reading. The bill passed the assembly 35 to 20 and was sent immediately on to the New Jersey Senate, which also suspended its rules and voted the bill through 14 to 0 on July 14, 1941. On July 21, 1941, Governor Charles Edison vetoed the bill returning it to the legislature with a letter chastising the members for approving a bill that he believed was counter to the needs of the national defense program. In his view, it was discriminatory towards defense workers; it did not consider the important passage of Title II of the Lanham Act by Congress on June 28, 1941 (another indication that money was only a partial driving force for opposition against Winfield); it created an unprecedented "Federal Island" in the State of New Jersey; it failed to consider that the State's constitution would not permit Winfield's new residents to elect local government officials until they had resided in the town for at least one year. It ignored that the bill's passage violated the New Jersey Constitution's specific guidelines concerning public announcements and opening hearings before a bill could be passed. Governor Edison's letter was read before the Legislature on July 28, 1941. At the reading's conclusion, there was no debate; Assemblyman Pascoe once again asked for a suspension of the rules, and the veto was immediately overturned by a vote of 33 to 24. The bill was immediately sent to the Senate, which suspended its rules on the same afternoon and overturned the Governor's veto by a vote of 11 to 5. Thus on July 28, 1941, Winfield Township, New Jersey, was established. Forty Clark Township opposition leaders were present in Trenton, New Jersey on July 28, 1941, and celebrated Winfield's establishment in the halls of Capital building.[29]

Winfield Township is a unique municipality in the United States. No other defense housing project had been established as a separate municipality. This unique status also created a number of unique problems. As the Elizabeth Daily Journal reported:

"Now Uncle Sam owns a town. Uncle Sam cannot tax himself or vote for himself. The occupants of houses cannot be taxed like a regular homeowner and he has promised them low monthly charges, but with all the benefits of living in town."

The construction of Winfield continued unabated and the establishment of Winfield Township resulted in the unforeseen effect of permitting the project's residents to control their own future. In an article entitled "County Clerk Places Winfield On His List," a local newspaper reported:

"Winfield has attained a modicum of recognition in these days of rebuffs and snubs among the powers. On all lists of municipalities required for records of official business in the office of County Clerk Henry G. Nulton, it now appears with its rebellious neighbors, Clark and Linden, the other towns. The fact that it is at the bottom of the list, insisted Abraham Grosman, in charge of revising the list, is that it alphabetically falls there, wrestling the last position from Westfield."[30]

Winfield's official history, written in 1976, even begins with the following:

"Winfield, Winfield Park, Winfield Township, is a big title for the 'baby of Union County.' Most of us use the plain 'Winfield' address simply because it is the quickest to write. People still say, 'Where's that?' However, after thirty-five years of the same question, we are accustomed to the remark. Sometimes the remarks given to our town, when a person knows where Winfield is, are far harder to swallow than when he is ignorant of its location. Some milder titles are, 'barracks', or 'oh, those places.' We are so tiny, that even state and county cartographers sometimes forget to put us on their maps. Sure, we feel a bit miffed at times, but we then look across our 'Green Acres' and realize our blessing."

But this local community pressure also had the positive effect of forcing Winfield's residents to work together more closely and form a more tightly knit community than could ever have been anticipated in the original site plan.

Construction

[edit]The construction of Winfield Park began on June 23, 1941, and was contracted through the MacEvoy Company of Newark, New Jersey, a company that built sections of the Newark subway, the Wanaque Reservoir, and was then working on developing reinforced concrete oil tankers (a project that failed spectacularly, and remnants of which can be still be seen off the coastline of Cape May, New Jersey). The entire Winfield project—254 buildings on 110 acres—eventually required 7500 gallons of paint; 2500 rolls of wallpaper; 5,500,000 board feet (13,000 m3) of lumber; and would employ 1,223 construction workers for five months.

From the start, work did not proceed well. Labor Union disputes stopped construction at least once. The construction work completed by the MacEvoy Company was exceptionally poor—so poor that it attracted the attention of the Truman Committee investigating abuses with the National Defense Program.[31] The investigation would eventually uncover the facts that the Winfield Park project lacked complete architectural or engineering plans and that financial records—at least the few that could be found—were criminally maintained. The project's construction was so badly botched that in many of the new buildings, residents discovered that nails had been hammered through water pipes, chimneys still contained the wooden forms used for their construction, roofs leaked, water pipes had never been soldered, floors were buckled, the paintwork was molding, sewer lines and pumps rarely worked, and many roads, sidewalks, and curbs had never been completed. On average, thirty-seven items needed to be repaired and/or replaced in each unit to make it habitable. To accomplish this repair work, the federal government spent an additional $100,000.00 and hired a new contractor, even after the project had officially been declared complete by Westbrook. The final cost for Winfield Park, including Federal Works Agency provided public works, came to $4,392,075.55 or $6,274.00/ unit; the Lanham Act specified a limit of $3,500.00. Continuing investigations uncovered that MacEvoy Company had manipulated bids and committed extensive fraud. MacEvoy rented and sold equipment and supplies to itself at an inflated cost, provided insurance to the government for its own work, employed the son-in-law of one of the government inspectors on the project, and generally milked the Winfield Park Project for everything that it could.[32] Much of this is outlined in a Life Magazine article from the November 30, 1942 issue.[33]

Community life

[edit]The construction difficulties outlined above had a major impact on the early days of Winfield Township. On November 30, 1941, the first 145 families (popularly referred to by township residents today as the "pioneers") arrived in their new town. A planned parade from Newark, New Jersey never materialized, and the families found themselves moving into barely completed, temporarily assigned units located at the edge of the project to make the units more easily accessible across the mud flats that were supposed to be the town's roads, curbs, and sidewalks. Most units were not yet connected to utilities and, in some cases, would not be for several months, even as winter approached. Early residents vividly remember huddling around car radios, the only radios available because of lack of electricity, to hear the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. No fire protection was provided, but the government hired a few guards and provided bicycles for "law enforcement". The school was not yet under construction, and all school-age children were sent to three different school districts. As expected, Winfield's neighbors were not warm to the new residents and were even heard to make rude comments as the township's residents trudged into their communities, in their mud-covered boots, to make food purchases. Transportation to the Kearny Shipyards was difficult if not impossible when the bus provided by the government broke down. Although one would think things could not be worse, there was an outbreak of polio in Winfield, and the entire town was quarantined. But even with these difficulties, there would soon be far more applicants than available units. Quickly the township's population increased, and the new residents were employed not only by the Kearny shipyards but also by Merck & Company, National Pneumatic Company, Lawrence Engineering, and Research Company, American Type Founders Co., American Gas Accumulator, Singer Manufacturing, and many other manufacturers.[34]

The cooperative nature of the town as a mutual housing project, the difficult physical environment of the town during its early days, and the animosity exhibited toward the new residents by their neighbors all served to bind the community together, creating a very strong and vigorous community life. Volunteer Police and Fire departments were quickly established by the residents, as was a volunteer Ambulance Squad and cooperative food store. Community leaders actively sought to discover Winfield's residents' special skills and interests. They utilized this information to organize and promote an astonishing number of clubs and social groups for a community of this size. Cooperative child care was provided in a building built by the community itself. Other community construction projects included a community center and shopping center. The great community event of the early days of Winfield Township was the opening of the town's grammar school on September 8, 1943. To increase the speed of repairs of structural deficiencies caused by the MacEvoy Company's poor workmanship, the residents of the Winfield participated in a rent strike against the federal government during the first year of occupancy; it was this strike that brought the attention of the Truman Committee to the Winfield Park project. A lasting problem caused by the township's unique status was the ill-defined relationship between the newly appointed Township Committee and the Mutual Housing Corporation. Both groups represented the same constituency; one (Mutual Housing) controlling all of the buildings and the other (Township Committee) with taxation authority; conflict and confusion were inevitable.[35]

After the war

[edit]

Winfield Park was the last of the Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Projects to be built and occupied. Because it was opened just before the start of the United States' involvement in World War II, it was also one of the last housing projects of a permanent nature to be built for the defense housing program. The current residents of Winfield believe that their town was built as temporary housing and are very proud of how well the structures have held up over the past 68 years thanks to their repair efforts; clearly, this grew out of the poor workmanship of the original construction.[citation needed]

The Winfield Park Mutual Housing Corporation purchased the Winfield Park project from the federal government for $1,358,567.21 on December 28, 1950, and entered into a 45-year mortgage bearing a 3% interest rate, which was completed on July 1, 1984.[36] By 1966, a Rutgers University economic study of the town reported that the town had "elements of a cooperative utopia, a feudal manor, and company town (with only one party and one company)." It continued on that:

"One of the apparent by-products of this situation (Town and Corporation being one and the same) is that the normal inter-party rivalry has been replaced by a running battle between the corporation and the township, both of which are elected by the same voters."

The 1966 study also made another observation about Winfield Park.

"One effect of outside resentment upon Winfield itself was to solidify sentiment among the inhabitants against their neighbors. If their neighbors didn't like Winfield, the feeling was definitely mutual. Another effect was to make the early Winfield settlers suspicious of all bureaucracy, including their own elected officers. In this respect, the trying experiences and disillusionment attending the early days of Winfield have made its citizens even more sensitive than usual to rumors respecting changes in the community structures."

This sensitivity was especially prevalent in the 1960s when residents began to realize that the town's property was worth far more than the structures built upon it. Although several experts have presented proposals to Winfield for more efficient and economical use of the property—ranging from selling the entire community and splitting the profits to moving every resident into a single high-rise building and then developing the remaining property for more profitable uses—residents have never considered any of these proposals very seriously. The residents have continually recommitted themselves to the mutual ownership concept.[37]

In August 2001, the entire township celebrated its 60th anniversary with a community picnic and a parade led by Grand Marshal Leona Harriot Burke (1917–2007), who had moved from Kearny, New Jersey to Winfield Park on the first move-in day for new residents on December 1, 1941. Mrs. Burke had also served as the first president of the Winfield Park Volunteer Fire Department's Ladies Auxiliary.

Sociological research

[edit]The residents of Winfield Park were participants during the mid-1940s in a study of social interactions and patterns within public housing projects. This was one of the first studies undertaken by Columbia University Bureau of Applied Social Research under the leadership of sociologist Robert K. Merton. Merton would become one of the most influential sociologists of the 20th century; he was known as the "Father of the focus group" and was the first sociologist to win a National Medal of Science (1994). During his career, Merton coined terms including "self-fulfilling prophecy" (in an article that dealt with Winfield) and "role model". Other sociologists involved in these studies included Paul Lazarsfeld, Patricia Salter West, and Marie Jahoda. Winfield Park was presented in several published articles by these researchers under the pseudonym "Craftown" and was presented as a homogeneous white middle-income public housing project. In these articles, "Craftown" was often compared and contrasted with "Hilltown," a racially integrated lower-income public housing project. An aspect of this research beyond interviewing every adult resident of the community was the decision to observe and provide detailed analysis and reports on community organizational meetings taking place during the summer and fall of 1945. In addition to the articles, there was also an unpublished manuscript on this research entitled Patterns of Social Life: Explorations in the Sociology and Social Psychology of Housing. When asked in 2002 why this manuscript had not been published, Merton described the period of its writing as being during the Red Scare of the post-war years and his fear, along with those of the other researchers, that the study could have negatively affected Winfield Park. [citation needed][38] Merton described the mutual housing projects as some of the closest examples of functioning socialist communities within the United States and as such, was one of the primary attractions for studying Winfield Park and its residents.

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the township had a total area of 0.18 square miles (0.47 km2), all of which was land.[1][2]

The township is bordered to the north and east by Linden and to the south and west by Clark.[39][40][41]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 2,719 | — | |

| 1960 | 2,458 | −9.6% | |

| 1970 | 2,184 | −11.1% | |

| 1980 | 1,785 | −18.3% | |

| 1990 | 1,576 | −11.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,514 | −3.9% | |

| 2010 | 1,471 | −2.8% | |

| 2020 | 1,423 | −3.3% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 1,392 | [10] | −2.2% |

| Population sources: 1950–1990[42] 2000[43][44] 2010[45][17][18] 2020[9] | |||

2010 census

[edit]The 2010 United States census counted 1,471 people, 706 households, and 382 families in the township. The population density was 8,320.1 per square mile (3,212.4/km2). There were 714 housing units at an average density of 4,038.5 per square mile (1,559.3/km2). The racial makeup was 96.40% (1,418) White, 0.95% (14) Black or African American, 0.00% (0) Native American, 0.14% (2) Asian, 0.07% (1) Pacific Islander, 1.09% (16) from other races, and 1.36% (20) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.39% (94) of the population.[17]

Of the 706 households, 20.8% had children under the age of 18; 39.4% were married couples living together; 12.5% had a female householder with no husband present and 45.9% were non-families. Of all households, 39.5% were made up of individuals and 16.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08 and the average family size was 2.83.[17]

17.3% of the population were under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 27.2% from 25 to 44, 31.4% from 45 to 64, and 15.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.9 years. For every 100 females, the population had 86.9 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 81.8 males.[17]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $55,323 (with a margin of error of +/− $6,372) and the median family income was $61,563 (+/− $8,257). Males had a median income of $54,034 (+/− $3,966) versus $38,333 (+/− $2,212) for females. The per capita income for the borough was $27,284 (+/− $1,840). About 7.3% of families and 7.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.5% of those under age 18 and 12.8% of those age 65 or over.[46]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 United States census[14] there were 1,514 people, 694 households, and 394 families residing in the township. The population density was 8,578.4 inhabitants per square mile (3,312.1/km2). There were 697 housing units at an average density of 3,949.2 per square mile (1,524.8/km2). The racial makeup of the township was 96.96% White, 0.33% African American, 0.20% Native American, 0.13% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 0.66% from other races, and 1.65% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.44% of the population.[43][44]

There were 694 households, of which 25.6% had children under 18 living with them, 40.9% were married couples living together, 13.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.1% were non-families. 38.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.6% had someone who was 65 years of age or older living alone. The average household size was 2.18, and the average family size was 2.92.[43][44]

In the township the population was spread out, with 20.9% under the age of 18, 5.9% from 18 to 24, 32.6% from 25 to 44, 24.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.1 males.[43][44]

The median income for a household in the township was $37,000, and the median income for a family was $47,167. Males had a median income of $41,133 versus $30,139 for females. The per capita income for the township was $21,565. About 2.8% of families and 7.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.7% of those under age 18 and 7.3% of those age 65 or over.[43][44]

Government

[edit]Local government

[edit]

Winfield Township is governed under the Township form of New Jersey municipal government, one of 141 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form, the second-most commonly used form of government in the state.[47] The governing body is comprised of the Township Committee, whose three members are elected directly by the voters at-large in partisan elections to serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with one seat coming up for election each year as part of the November general election in a three-year cycle.[7][48] At an annual reorganization meeting, the Township Committee selects one of its members to serve as Mayor. The Mayor, in addition to voting as a member of the Township Committee, presides over the committee's meetings and carries out ceremonial duties.

As of 2024[update], members of the Winfield Township Committee are Mayor Joseph P. Byrne (D, term on committee and as mayor ends December 31, 2024), Adam Koomer (D, 2026), and Robert Reilly (R, 2025).[49][50][51][52]

In March 2016, Sue E. Wright was appointed to fill the term expiring in December 2017 that had been held by Oneida M. Braithwaite.[53]

In 2018, the township had an average property tax bill of $3,574, the lowest in the county, compared to an average bill of $11,278 in Union County and $8,767 statewide.[54][55]

Federal, state and county representation

[edit]Winfield Township is located in the 7th Congressional District[56] and is part of New Jersey's 22nd state legislative district.[57][58][59]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 7th congressional district is represented by Thomas Kean Jr. (R, Westfield).[60] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027) and Andy Kim (Moorestown, term ends 2031)[61][62]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 22nd legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Nicholas Scutari (D, Linden) and in the General Assembly by Linda S. Carter (D, Plainfield) and James J. Kennedy (D, Rahway).[63]

Union County is governed by a Board of County Commissioners, whose nine members are elected at-large to three-year terms of office on a staggered basis with three seats coming up for election each year, with an appointed County Manager overseeing the day-to-day operations of the county. At an annual reorganization meeting held in the beginning of January, the board selects a Chair and Vice Chair from among its members.[64] As of 2025[update], Union County's County Commissioners are:

Rebecca Williams (D, Plainfield, 2025),[65] Joesph Bodek (D, Linden, 2026),[66] James E. Baker Jr. (D, Rahway, 2027),[67] Michele Delisfort (D, Union Township, 2026),[68] Sergio Granados (D, Elizabeth, 2025),[69] Bette Jane Kowalski (D, Cranford, 2025),[70] Vice Chair Lourdes M. Leon (D, Elizabeth, 2026),[71] Alexander Mirabella (D, Fanwood, 2027)[72] and Chair Kimberly Palmieri-Mouded (D, Westfield, 2027).[73][74]

Constitutional officers elected on a countywide basis are: Clerk Joanne Rajoppi (D, Union Township, 2025),[75][76] Sheriff Peter Corvelli (D, Kenilworth, 2026)[77][78] and Surrogate Christopher E. Hudak (D, Clark, 2027).[79][80]

Politics

[edit]As of March 2011, there were a total of 1,030 registered voters in Winfield Township, of which 383 (37.2% vs. 41.8% countywide) were registered as Democrats, 180 (17.5% vs. 15.3%) were registered as Republicans and 467 (45.3% vs. 42.9%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were no voters registered to other parties.[81] Among the township's 2010 Census population, 70.0% (vs. 53.3% in Union County) were registered to vote, including 84.7% of those ages 18 and over (vs. 70.6% countywide).[81][82]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 426 votes (59.0% vs. 66.0% countywide), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 271 votes (37.5% vs. 32.3%) and other candidates with 13 votes (1.8% vs. 0.8%), among the 722 ballots cast by the township's 1,053 registered voters, for a turnout of 68.6% (vs. 68.8% in Union County).[83][84] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 406 votes (51.0% vs. 63.1% countywide), ahead of Republican John McCain with 371 votes (46.6% vs. 35.2%) and other candidates with 13 votes (1.6% vs. 0.9%), among the 796 ballots cast by the township's 1,063 registered voters, for a turnout of 74.9% (vs. 74.7% in Union County).[85] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 420 votes (51.3% vs. 58.3% countywide), ahead of Republican George W. Bush with 389 votes (47.6% vs. 40.3%) and other candidates with 6 votes (0.7% vs. 0.7%), among the 818 ballots cast by the township's 1,051 registered voters, for a turnout of 77.8% (vs. 72.3% in the whole county).[86]

In the 2017 gubernatorial election, Democrat Phil Murphy received 213 votes (50.8% vs. 65.2% countywide), ahead of Republican Kim Guadagno with 199 votes (47.5% vs. 32.6%), and other candidates with 7 votes (1.7% vs. 2.1%), among the 433 ballots cast by the township's 1,041 registered voters, for a turnout of 41.6%.[87][88] In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 61.0% of the vote (282 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 37.0% (171 votes), and other candidates with 1.9% (9 votes), among the 477 ballots cast by the township's 1,048 registered voters (15 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 45.5%.[89][90] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 264 votes (51.9% vs. 41.7% countywide), ahead of Democrat Jon Corzine with 189 votes (37.1% vs. 50.6%), Independent Chris Daggett with 38 votes (7.5% vs. 5.9%) and other candidates with 8 votes (1.6% vs. 0.8%), among the 509 ballots cast by the township's 1,049 registered voters, yielding a 48.5% turnout (vs. 46.5% in the county).[91]

Sports

[edit]Even though Winfield is a small community, they do have a sports program for their elementary school students. They play soccer, basketball, and baseball. They also have a year-round recreational sports program.

Education

[edit]The Winfield Township School District serves public school students in pre-kindergarten to eighth grade at Winfield School.[92] As of the 2018–19 school year, the district, comprised of one school, had an enrollment of 139 students and 18.0 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 7.7:1.[93] In the 2016–17 school year, Winfield had the 19th-smallest enrollment of any school district in the state, with 140 students.[94] The school offers a class for students with special needs.

Public school students in ninth through twelfth grades attend David Brearley High School in Kenilworth, as part of a sending/receiving relationship with the Kenilworth Public Schools.[95] As of the 2018–19 school year, the high school had an enrollment of 757 students and 63.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 11.9:1.[96] Before the current sending relationship had been established with Brearley, students had attended Rahway High School until a decision by the New Jersey Department of Education in March 2000 allowed for termination of the relationship.[97]

Students in public school for grades 9–12 may also attend the schools of the Union County Vocational Technical Schools in Scotch Plains.[98]

Transportation

[edit]Roads and highways

[edit]

As of May 2010[update], the township had a total of 3.10 miles (4.99 km) of roadways, of which 3.00 miles (4.83 km) were maintained by the municipality and 0.10 miles (0.16 km) by Union County.[99]

North Stiles Street (County Route 615) forms the northeastern edge of Winfield Township. In addition, a small piece of Raritan Road (County Route 607) forms the northern border of the township.[100]

The Garden State Parkway, west of the Rahway River, just misses the municipality by about 100 yards and is accessible at Exit 136 on the Cranford / Clark border.[101]

Public transportation

[edit]NJ Transit provides bus service between the township and the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan on the 112 route, with local service offered on the 56 and 57 routes.[102]

Passenger rail service is provided by NJ Transit from the neighboring communities of Cranford on the Raritan Valley Line and from the Linden station on the Northeast Corridor.

Newark Liberty International Airport is approximately 12 minutes away in Newark / Elizabeth. Linden Airport, a general aviation facility, is in Linden.

Notable people

[edit]People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Winfield Township include:

- Tom Dugan (born 1961), actor who starred in the music video Legs by ZZ Top[103]

- Dan Graham (born 1942), conceptual artist, art critic[104][105]

- Jeffrey Moran (born 1946), Ocean County Surrogate and former member of the New Jersey General Assembly from 1986 to 2003, where he represented the 9th Legislative District[106]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 242. Accessed May 30, 2024.

- ^ New Jersey General Assembly, Minutes of Votes and Proceedings of the One Hundred and Sixty-Fifth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey. MaCrellish and Quigley Co. State Printers. Trenton, New Jersey. 1941. p. 1188

- ^ "Township Committee". Township of Winfield. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Municipal Departments, Township of Winfield. Accessed April 29, 2022.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 90.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Township of Winfield, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Winfield, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed May 25, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Winfield, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed September 30, 2014.

- ^ a b U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic codes for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Winfield township, Union County, New Jersey Archived February 10, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Winfield township[permanent dead link], New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed May 25, 2013.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Astudillo, Carla. "The 10 tiniest towns in New Jersey (they're really small)", NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, November 1, 2016, updated May 16, 2019. Accessed March 5, 2020. "We used square mile data from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection to rank the ten municipalities with the smallest area size.... 6. Winfield Township Situated close to Linden, Winfield township was created as part of a large 700-unit mutual housing project for defense workers of the Kearny shipyards in 1941."

- ^ "Development of a Park Site", Architectural Record, Volume 90, Number 5, November 1941, p. 86-87

- ^ House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 3213, p.228-230, 233; Elizabeth Daily Journal, Nov. 29, 1941, June 29, 1941.

- ^ House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 3213, p.230, 231, 235, 237, 233, 244; House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 5211, p. 153, 169,170–173, 225; Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, pt.8 p,.6066; Elizabeth Daily Journal, April 2, 1941, p, July 29, 1941, Nov. 29, 1941.

- ^ Elizabeth Daily Journal, July 29, 1941, April 2, 1941

- ^ Kaledin, Eugenia. Daily Life in the US 1940–1959: Shifting Worlds. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT. 2000. p. 129

- ^ Rutgers University Bureau of Economic Research. An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, New Jersey: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources. New Brunswick, N.J.: Bureau of Economic Research, 1965. p. 10

- ^ 1/4 of the Winfield Park project was within the jurisdiction of the Town of Linden and a smaller amount in the Town of Cranford. Initially, Linden verbally supported the Clark opposition but then offered to cede all of the land involved to Clark; this was not favorably received by the Clark neighbors. Linden and Cranford were willing to allow Clark to carry the battle to stop Winfield Park, or at least someone else would become responsible for the costs. Elizabeth Daily Journal, July 29, 1941, April 26, 1941, Nov. 29, 1941; Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, pt.8, p. 6066; House of Representatives Hearings on Message of President of the United States, p.15; Rutgers Bureau of Economic Research, "An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, N.J.: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources", p. 10; House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 5211, p. 225–226

- ^ Elizabeth Daily Journal, July 29, 1941; House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 5211, p. 168, 170–171, 225. "US Handed Boom Town." Elizabeth Daily Journal. July 29, 1941.

- ^ New Jersey General Assembly, "Minutes of Votes and Proceedings of the One Hundred and Sixty-Fifth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey," pp. 1010, 1027–1029, 1089, 1117–1119, 1178, 1188; New Jersey Senate, "Journal of Ninety-Seventh Senate of the State of New Jersey," pp. 847-849, 929–930; Elizabeth Daily Journal, July 22, 1941, July 29, 1941.

- ^ Elizabeth Daily Journal, July 29, 1941, Aug. 2, 1941; Rutgers Bureau of Economic Research, An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, N.J.: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources, p.7.

- ^ "Business: Two Scandals", Time (magazine)Time, November 30, 1942. Accessed September 30, 1942.

- ^ Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, pt.8, p. 6051-6120

- ^ Truman Committee Exposes Housing Mess. Life Magazine. November 30, 1942.

- ^ Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, pt.8, p.6050, 2060, 6066; Elizabeth Daily Journal, November 29, 1941; Winfield Cultural and Heritage Commission, History of Winfield, p.6; Rutgers Bureau of Economic Research, An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, N.J.: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources, p.7-9; House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 3213, p.233.

- ^ Winfield Cultural and Heritage Commission, History of Winfield, p.5,7–10; Elizabeth Daily Journal, November 29, 1941, December 2, 1941, August 2, 1941; Rutgers Bureau of Economic Research, An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, N.J.: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources, p.11; Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, pt.8, p.6048, 6051–6052.

- ^ Winfield Park 60th Anniversary Celebration Booklet, Winfield Mutual Housing Corporation, Winfield Park, New Jersey. September 8, 2001.

- ^ Rutgers Bureau of Economic Research, An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, N.J.: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources, p. 22,35; Winfield Cultural and Heritage Commission, History of Winfield, p.15,20

- ^ Kaledin, Eugenia. Daily Life in the US 1940–1959: Shifting Worlds. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT. 2000. p. 85

- ^ Areas touching Winfield, MapIt. Accessed March 11, 2020.

- ^ Union County Municipal Profiles, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed March 11, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ Table 6: New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1940 - 2000, Workforce New Jersey Public Information Network, August 2001. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for Winfield township, New Jersey Archived November 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Winfield township, Union County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 25, 2013.

- ^ Census 2010: Union County, Asbury Park Press. Accessed June 15, 2011.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for Winfield township, Union County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 25, 2013.

- ^ Inventory of Municipal Forms of Government in New Jersey, Rutgers University Center for Government Studies, July 1, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Forms of Municipal Government in New Jersey", p. 7. Rutgers University Center for Government Studies. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Union County Elected Officials, Union County, New Jersey Clerk. Accessed May 28, 2024.

- ^ General Election November 7, 2023 Official Results, Union County, New Jersey, updated November 22, 2023. Accessed January 3, 2024.

- ^ General Election November 8, 2022 Official Results, Union County, New Jersey, updated November 21, 2022. Accessed January 3, 2024.

- ^ General Election November 2, 2021 Official Results, Union County, New Jersey, updated November 15, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- ^ Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Township Committee March 16, 2015, Winfield Township. Accessed August 5, 2016. "At this time Mayor Genz diverted from the agenda to swear in Sue E. Wright as a member of the Township Committee and presented Res. # 15-17 appointing Twp. Commissioner and Deputy Mayor Sue E. Wright."

- ^ 2018 Property Tax Information, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated January 16, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

- ^ Marcus, Samantha. "These are the towns with the lowest property taxes in each of N.J.’s 21 counties", NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, April 30, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019. "New Jersey’s average property tax bill may have hit $8,767 last year — a new record — but taxpayers in some parts of the state pay just a fraction of that.... The average property tax bill in Winfield Township was $3,574 in 2018, the lowest in Union County."

- ^ Plan Components Report, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 23, 2011. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ 2019 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- ^ Districts by Number for 2011-2020, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Congressman Malinowski Fights For The Corporate Transparency Act", Tom Malinowski, press release dated October 23, 2019. Accessed January 19, 2022. "My name, Tom Malinowski. My address, 86 Washington Street, Rocky Hill, NJ 08553."

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/andy-kim-new-jersey-senate/

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 22, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 12, 2024.

- ^ Home Page, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Chair Rebecca Williams Archived November 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Vice Chair Christopher Hudak Archived May 28, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner James E. Baker Jr., Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Angela R. Garretson, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Sergio Granados, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Bette Jane Kowalski, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Lourdes M. Leon, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Alexander Mirabella, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Commissioner Kimberly Palmieri-Mouded, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ 2022 County Data Sheet, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ County Clerk Joanne Rajoppi, Union County Votes. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Sheriff Peter Corvelli, Union County Sheriff's Office. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Office of the Union County Surrogate, Union County, New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b In the short history of the community, no Republican has ever been elected to a township office. Voter Registration Summary - Union, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 23, 2011. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ GCT-P7: Selected Age Groups: 2010 - State -- County Subdivision; 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ Presidential November 6, 2012 General Election Results - Union County Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 15, 2013. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast November 6, 2012 General Election Results - Union County Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 15, 2013. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Union County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election: Union County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ "Governor - Union County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. December 21, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 7, 2017 - General Election Results - Union County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. December 21, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Governor - Union County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 5, 2013 - General Election Results - Union County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2009 Governor: Union County Archived October 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- ^ New Jersey School Directory for the Winfield Township School District, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed February 1, 2024.

- ^ District information for Winfield Township, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- ^ Guion, Payton. "These 43 N.J. school districts have fewer than 200 students", NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, September 2017. Accessed January 30, 2020. "Based on data from the state Department of Education from the last school year and the Census Bureau, NJ Advance Media made a list of the smallest of the small school districts in the state, excluding charter schools and specialty institutions.... 19. Winfield Township; Enrollment: 140; Grades: Pre-K-8; County: Union"

- ^ David Brearly Middle/High School 2016 School Report Card, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed June 23, 2020. "David Brearley Middle-High School serves students in Grades 7-12 from Kenilworth, Winfield, and surrounding communities that who participate in the School Choice Program."

- ^ School data for David Brearley Middle/High School, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- ^ Commissioner of Education's Decision in Board of Education of the Township of Winfield, Union County v. Board of Education of the City of Rahway, Union County, New Jersey Department of Education, March 2, 2000. Accessed June 23, 2020. "Accordingly, the Initial Decision is adopted as the final decision in this matter for the reasons expressed therein. Winfield's application for severance of its sending-receiving relationship with Rahway is hereby granted, subject to its entering into a new sending-receiving relationship with Kenilworth for a minimum of five years. Withdrawal shall be phased out over a four-year period, beginning with the incoming 9th grade class in September 2000."

- ^ Full-Time Opportunities, Union County Vocational Technical Schools. Accessed November 12, 2013. "Applicants are selected from a diverse population of eighth grade students in each of the twenty-one municipalities in Union County."

- ^ Union County Mileage by Municipality and Jurisdiction, New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2010. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Union County Route 607 Straight Line Diagram, New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2000. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Travel Resources: Interchanges, Service Areas & Commuter Lots, New Jersey Turnpike Authority. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Union County Bus / Rail Connections, NJ Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as of January 28, 2010. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Schulz, Mike. "Judges of Posterity: Quad City Arts Visiting Artist Tom Dugan Portrays Robert E. Lee", River Cities' Reader, January 17, 2007. Accessed November 12, 2013. "Dugan grew up in the small New Jersey town of Winfield – where, during performances in grammar and high school, the fledgling actor 'found a very comfortable place performing in theatre' – and eventually earned a degree in theatre from Montclair University, located in the upper region of the state."

- ^ Rosenbaum-Kranson, Sarah. www.museomagazine.com/DAN-GRAHAM "Interview: Dan Graham", Museo magazine. Accessed November 12, 2013. "DAN GRAHAM: I was born in Illinois. I grew up in Winfield and then Westfield, New Jersey."

- ^ Dan Graham Biography Archived April 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, MetroArtWork. Accessed March 14, 2014. "He was born in Urbana, Illinois, but moved to Winfield Park, New Jersey at age 3, and then to Westfield, NJ at age 13."

- ^ About The Surrogate, Ocean County, New Jersey. Accessed November 12, 2013.

References

[edit]- "700 Tenants Seek to Buy War Town: Cooperative Starts Action to Exercise Option on Winfield Park, NJ, Owned by US." The New York Times. February 3, 1947. p. 21.

- Bauer, Catherine. "Social Questions in Housing and Community Planning" in The Journal of Social Issues, Volume VII Numbers 1&2, 1951. p. 1–34

- "Co-Op Stores Sold: Residents of Winfield, NJ Quit $250,000 a Year Business." The New York Times. March 22, 1948. p. 35.

- "Defense Homes Get 135 Tenants: Workers' Families Move Into New Federal Development in Winfield, NJ." The New York Times. December 2, 1941. p. 26.

- "Defense Housing Project to be Built in Clark: Clark Site Fixed Opponents Told." Elizabeth Daily Journal. April 2, 1941.

- "Defense Housing Sold: Deal With US for Development in NJ Authorized." The New York Times. November 18, 1949. p. 47.

- "Edison Veto Hits 'Winfield' Setup: Governor, While Sympathizing with Clark, Linden, Fears Impression of Discrimination Against Defense Workers." Elizabeth Daily Journal. July 22, 1941.

- "Fraud Charges Denied; MacEvoy Groups in Jersey Disavow Housing Project Deals". The New York Times. April 7, 1943.

- "Ideals of Community Living Are to Be Stressed by Winfield Manager." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works. "Urban Housing: The Story of the P.W.A. Housing Division 1933–1936, Bulletin No. 2." Washington, D.C.: GPO, August, 1936.

- Federal Works Agency (United States Housing Authority). "Four Years of Public Housing." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1941.

- Federal Works Agency. "1st Annual Report." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1940.

- Federal Works Agency. "2nd Annual Report." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1941.

- Federal Works Agency. "3rd Annual Report." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1942.

- Form, William H.. "Stratification in Low and Middle Income Housing Areas" in Journal of Social Issues, Volume VII, Number 1&2, 1951. p. 109–131.

- Friedland, Sandra. "Winfield Journal: Painful Debate Over Closing Town's Only School." The New York Times. February 7, 1993.

- Ground Breaking Ceremonies. Clark Township Defense Housing Project. Federal Works Agency. Saturday, June 14, 1941.

- "Grants Winfield Delay: PHA Gives Month's Extension on Purchase of Housing." The New York Times. September 13, 1949. p. 51.

- House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 3213, (A Bill to Expedite Further the Provision of Housing in Connection With National Defense, and to Provide Public Works in Relation to such Housing and other National Defense Activities, and For Other Purposes) and House Resolution 3570, (A Bill Authorizing An Appropriation for Providing Additional Community Facilities Made Necessary By National Defense Activities and For Other Purposes). "Hearings Before the Committee On Public Buildings and Grounds, March 4,5,6,7,12 and 13, 1941." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1941.

- House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 3486, (A Bill to Authorize An Appropriation of An Additional $150,000,000 for Defense Housing). "Hearings Before the Committee On Public Buildings and Grounds, February 21, 1941." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1941.

- House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 5211, (A Bill to Authorize An Appropriation of An Additional $300,000,000 For Defense Housing). "Hearings Before the Committee On Public Buildings and Grounds, July 9,10,11,15,16,17,18,22,23,1941." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1941.

- House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolution 7312, (A Bill to Increase by $600,000,000 The Amount Authorized To Be Appropriated For Defense Housing Under the Act of October 14, 1940, As Amended). "Hearings Before the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, June 9,10,11,12,16,17,18,19,23,24,25 and 26, 1942." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1942.

- House of Representatives Hearings on House Resolutions 6482 and 6483, (Bills to Amend the Act Entitled 'An Act To Expedite the Provision of Housing In Connection with National Defense and For Other Purposes'). "Hearings Before the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, January 29 and 30, February 3, 1942, March 11,12,17,18,19 and 24, 1942." Washington, D.C." GPO, 1942.

- House of Representatives Hearings on Message from the President of the United States, (A Draft of a Proposed Bill to Increase by $400,000,000 the Amount Authorized to be Appropriated for Defense Housing). "Hearings Before the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, May 18,19,20,21,26 and 27, June 1,2,4,8, and 10, 1943." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1943.

- Jahoda, Maria, Patricia Salter West. "Race Relations in Public Housing," in Journal of Social Issues, Volume VII, Number 1&2, 1951. p. 132–139.

- "Jersey Bill Stirs Housing Officials: Measure to Make Clark Township Project a Separate Area is Held Serious Precedent." The New York Times. July 16, 1941. p. 12.

- Kaledin, Eugenia. Daily Life in the US 1940–1959: Shifting Worlds. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT. 2000.

- "Large Housing Job in Jersey Scored: Senate Committee Asks Justice Department to Investigate 'Bad' Winfield Project'." The New York Times. November 20, 1942. p. 17.

- "Launch Housing Work in Clark." Elizabeth Daily Journal. June 16, 1941.

- Lazarsfeld and Robert K. Merton. "Friendship as Social Process: A Substantive and Methodological Analysis" in Morroe Berger, Theodore Abel and Charles H. Page. Freedom and Control in Modern Society. Octagon Books, New York, 1978

- "Many Difficult Engineering Problems Are Solved in Building Winfield." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- Merton, Robert K. "The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy." The Antioch Review, Summer 1948. p. 193–210.

- Merton, Robert K. "Discrimination and the American Creed." In R.M. MacIver ed. Discrimination and National Welfare. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949.

- Merton, Robert K. "Selected Problems of Field Work in the Planned Community." American Sociological Review, Volume 12, Issue 3, June 1947. p. 304–312

- Merton, Robert K. "Social Psychology of Housing." In Wayne Dennis, ed. Current Trends in Social Psychology. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1948.

- Merton, Robert K. and Patricia L. Kendall, "The Focused Interview." American Journal of Sociology, Number 51, 1946. p. 547–557.

- Merton, Robert K. and Paul Lazarsfeld. "Friendship aa a Social Process: A Substantive and Methodological Analysis." In Monroe Berger, Theodore Abel, and Charles Page, eds. Freedom and Control in Modern Society. New York, N.Y.: Van Nostrand, 1954.

- Merton, Robert K. and Patricia Salter West. "The First Year's Work, 1945–1946: An Interim Report on the Columbia Lavanburg Researches on Human Relations in the Planned Community", June 1946.

- "Moving Day in Winfield." Elizabeth Daily Journal. December 2, 1941.

- National Housing Agency (Federal Public Housing Authority). "Public Housing: The Work of the Federal Public Housing Authority." Washington, D.C.: GPO, March, 1946.

- National Housing Agency. "Housing for War and the Job Ahead: A Common Goal for Communities...for Industry, Labor and Government." Washington, D.C.: GPO, April, 1944.

- National Housing Agency. "Housing Practices – War and Prewar: Review of Design and Construction, National Housing Bulletin 5." Washington, D.C.: GPO, May, 1946.

- National Housing Agency. "Public Housing: The Work of the Federal Public Housing Authority." Washington, D.C.: GPO, March, 1946.

- National Housing Agency. "Second Annual Report." Washington, D.C.: GPO, Oct., 1944.

- National Housing Agency. "The Mutual Home Ownership Program." Washington, D.C.: Federal Public Housing Authority, January, 1946.

- National Housing Agency. "War Housing In the United States." Washington, D.C.: GPO, April, 1945.

- National Housing Agency/ "Mutual Housing A Veteran's Guide: Organizing, financing, constructing, and operating several selected types of cooperative housing associations, with special reference to Available Federal Aids." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1946.

- "New Defense Community: Winfield, NJ, Starts Its Existence as a Municipality." New York Times. August 4, 1941. p. 15.

- New Jersey General Assembly. "Minutes of Votes and Proceedings of the One Hundred and Sixty-Fifth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey." Trenton, N.J.: MacCrellish and Quigley Co., 1941.

- New Jersey Senate. "Journal of the Ninety-Seventh Senate of the State of New Jersey Being the One Hundred and Sixty Fifth Session of the Legislature." Trenton, N.J.: MacCrellish and Quigley Co., 1941.

- "Old Barracks as Co-Ops." The New York Times. October 3, 1976.

- "Pay Rise, Ends Winfield Strike." The New York Times. June 13, 1954. p. 17.

- "Pioneer Residents of Winfield Will be Given Welcome Monday: US Township to Be Opened." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- "Price Set on Housing: Government Fixes $1,400,000 for New Jersey Development." The New York Times. November 9, 1949. p. 48.

- Public Housing Administration. "First Annual Report Public Housing Administration." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1948.

- "Record Number of Carpenters Has Part in Erecting of Winfield Homes." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- Rutgers University Bureau of Economic Research. "An Economic Profile of Winfield Park, New Jersey: Including Alternatives For the Use of Community Resources". New Brunswick, N.J.: Bureau of Economic Research, 1965.

- "School Given to Town: Federal Agency Transfers Control to Winfield, NJ Board." The New York Times. November 23, 1950. p. 38.

- Selvin, Hanan C. "The Interplay of Social Research and Social Policy in Housing" in Journal of Social Issues, Volume VII, Number 1&2, 1951. p. 172–185.

- Senate Hearings on Proposed General Housing Act of 1945. " Hearings Before the Committee on Banking and Currency, Part 2, December 6,7,11,12,13,14,17,18, 1945, January 24 and 25, 1946, Revised." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1946.

- Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, (A Resolution Authorizing and Directing An Investigation of the National Defense Program). "Investigation of the National Defense Program, Part 8, October 3,7,8,9,14,15,21,22,23,24,27,28,29, and 31, 1941." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1942.

- Senate Hearings on Senate Resolution 71, (A Resolution Authorizing and Directing An Investigation of the National Defense Program). "Investigation of the National Defense Program, Part 15, November 18,19, 23, 24 and 25, 1942." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1943.

- Szylvian Bailey, Kristin. The Federal Government and the Cooperative Housing Movement, 1917–1955. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation Carnegie-Mellon University, 1988.

- Szylvian, Kristin M. "Our Mutual Friend: A Progressive Housing Legacy from the 1940s." Designer Builder: A Journal of the Human Environment. Vol. 111 No. 9. January 1997.

- Szylvian, Kristin M., "The Federal Housing Program During World War II" in From Tenements to The Taylor Homes: In Search of An Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth Century America edited by John F. Bauman, Roger Biles and Kristin Szylvian. Pennsylvania State Press, 2000.

- "Talents Listed for Like Tastes: Winfield Tenants to be Grouped for Social Life." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- "Tenants in Winfield Set to Buy Project." The New York Times. September 5, 1948. p. R2.

- Time Magazine, "Not for Rent, Not for Sale", June 2, 1941

- "To Buy Jersey Housing: Winfield Group Ready to Acquire Government-Owned Project." The New York Times. May 13, 1947. p. 43.

- "Town is Quarantined: Third Paralysis Death Affects Jersey War Housing Area." The New York Times. September 9, 1942. p. 16.

- "Truman Committee Exposes Housing Mess." Life Magazine. November 29, 1942.

- United States Housing Authority. "Annual Report of the United States Housing Authority." Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1940.

- "US Cuts Housing Price: Asking $50,000 Less for Project in Winfield, NJ." The New York Times. October 14, 1949. p. 47.

- "US Handed Boom Town: Winfield, Created Over Edison's Veto, Has Lone Status. Puzzle for Government Aides." Elizabeth Daily Journal. July 29, 1941. p. 11.

- "US Indicts 3 Firms For Housing Frauds: 5 Individuals Also Accused in Winfield, NJ Project." The New York Times. March 31, 1943. p. 15.

- "US Owned Jersey Town Appeals for Coal; 100,000 Homes Here Still Lacking Fuel." The New York Times. October 21, 1943. p. 29.

- "US to Resume Rule of Winfield Housing: Reason for Shift From Mutual Control Not Explained." The New York Times. April 7, 1944. p. 36.

- Winfield Cultural and Heritage Commission. History of Winfield. Winfield Township, N.J.: Winfield Cultural and Heritage Commission, 1976.

- "Winfield Roads Get Sea Names: Shipyard Workers Honored in Choosing Titles." Elizabeth Daily Journal. November 29, 1941.

- "Winfield Sale Awaited: Meeting Tonight to Hear Terms of Purchase from Government." The New York Times. August 11, 1949. p. 35.

- "Winfield Seeks Town Officers: Pascoe Asked to Sponsor Bill in Legislature: Would Give Governor Appointive Power." Elizabeth Daily Journal. December 9, 1942.