Williston School

34°13′52″N 77°56′06″W / 34.231°N 77.935°W

Williston School is a school in Wilmington, North Carolina. It was first founded in 1866 by the abolitionist American Missionary Association after the Union army occupied the city during the civil war. It was intended for freed slaves and initially had 450 pupils divided into five departments: primary, intermediate, advanced, normal and industrial.[1] As it developed, it became known by a variety of names including Williston Graded School, Williston Primary and Industrial School and Williston High School. The original site was on Seventh Street but in 1915, the institution moved to a new campus on Tenth Street and new buildings were constructed in 1933, 1937 and 1954. The institution was closed as a high school in 1968 as part of desegregation and this caused disturbances resulting in the Wilmington Ten. The remaining school on the site is now Williston Middle School of Math, Science & Technology.

History

[edit]

It was based upon a school for freed slaves which had been founded in 1866 and named after Samuel Williston, a Massachusetts button maker and philanthropist. That was on Seventh Street but, in 1915, a new building was constructed on Tenth and Church which opened in 1916 as Williston Industrial School and, in 1923, this became the first accredited high school for blacks in North Carolina.[3] A new building was opened in 1933 and then rebuilt when it was destroyed by fire in 1936. That building was then closed in 1954 after a lawsuit and replaced by another new building on South Tenth Street. The lawsuit had been brought by Dr Hubert A. Eaton, a local civil-rights activist who repeatedly pressed for greater equality of education. At the time, the school was comparatively deprived of resources such as new textbooks but its performance was the best of the black schools in the state.[4]

Martin Luther King Jr. was scheduled to speak at the school gymnasium on April 4, 1968.[5] He changed his plans, staying in Tennessee, and was assassinated there that same day.[6] Black high school students protested in Wilmington on the following day, making a march to City Hall.[7] Later that year, desegregation plans for Wilmington were disputed in federal court.[2] The school was closed as a high school as the Board of Education did not want to spend the sums required to improve the school to the standard of white schools nor to send white students there. The black students were moved to the previously all-white high schools of New Hanover and Hoggard, where they complained of inadequate provision.[6] Further protests and disturbances resulted in the notorious case of the Wilmington Ten.[6]

Notable faculty and staff

[edit]Mary Washington Howe teacher and principal, 1875-1890s[8]

Lethia Sherman Hankins, alumni and teacher from 1959-1968

Notable alumni

[edit]

- Robert Robinson Taylor, architect who helped Booker T. Washington construct the Tuskegee Institute.[10]

- Jimmy Heath (1943), jazz saxophonist known as "Little Bird".[2]

- Althea Gibson (1949), tennis champion – the first black player to win grand slam events.[2]

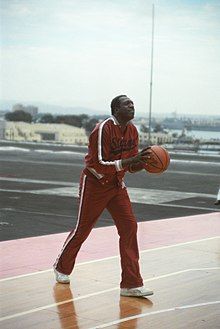

- Meadowlark Lemon (1952), star basketball player with the Harlem Globetrotters.[2]

- Joseph McNeil (1959), one of the Greensboro Four and air-force general.[2]

- Phillip Clay (1964), chancellor of MIT.[2]

- Sam Bowens, major league baseball player.[3]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1870, p. 249

- ^ a b c d e f g Ben Steelman (23 April 2010), "What is the history of Williston High School?", The Star-News

- ^ a b Fonvielle 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Marimar McNaughton (July 2015), "The Greatest School Under the Sun", Wrightsville Beach Magazine: 46–59

- ^ Godwin 2000, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Greene, Gabbidon, ed. (2009), "Wilmington Ten", Encyclopedia of Race and Crime, SAGE, pp. 905–906, ISBN 9781452266091

- ^ Godwin 2000, p. 213.

- ^ "Dedication to education: Mary Washington Howe". Wilmington Star News. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "Althea Gibson", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2014

- ^ Clarence G. Williams (13 January 1998), From 'Tech' to Tuskegee

Sources

[edit]- Fonvielle, Chris Eugene (2007), Historic Wilmington & the Lower Cape Fear, HPN Books, ISBN 9781893619685

- Godwin, John L. (2000), Black Wilmington and the North Carolina Way, University Press of America, ISBN 9780761816829

External links

[edit]- Collection of Williston Yearbooks

- Class of 1931 – photographed by Louis T. Moore

- Williston Middle School of Math, Science & Technology – website of the current institution