Douglas Gretzler

Douglas Edward Gretzler | |

|---|---|

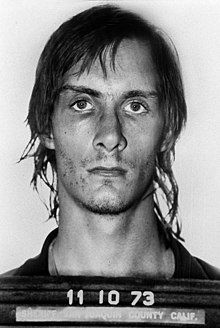

Booking photo of Douglas Gretzler, taken after his arrest (November 10, 1973) | |

| Born | May 21, 1951 |

| Died | June 3, 1998 (aged 47) |

| Cause of death | Execution by lethal injection |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Motive |

|

| Conviction(s) | California First degree murder (x9) Arizona First degree murder (x2) Kidnapping Robbery (x2) Burglary |

| Criminal penalty | California Life imprisonment Arizona Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 17 (11 convictions) |

Span of crimes | October 18 – November 7, 1973 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California, Arizona |

Date apprehended | November 8, 1973 |

| Imprisoned at | Florence State Prison |

Willie Luther Steelman | |

|---|---|

Booking photo of Willie Steelman, issued to the media prior to his arrest in November 1973 | |

| Born | March 21, 1945 |

| Died | August 7, 1986 (aged 41) Maricopa County Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Liver cirrhosis |

| Criminal status | Died in prison while awaiting execution |

| Motive |

|

| Conviction(s) | California First degree murder (x9) Robbery (x5) Arizona First degree murder (x2) Kidnapping (x1) Robbery (x2) Burglary (x1) |

| Criminal penalty | California Life imprisonment Arizona Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 17 (11 convictions) |

Span of crimes | October 18, 1973 – November 7, 1973 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California, Arizona |

Date apprehended | November 8, 1973 |

| Imprisoned at | Florence State Prison |

Douglas Edward Gretzler (May 21, 1951 – June 3, 1998)[3] was an American serial killer who, together with accomplice Willie Steelman, committed seventeen murders in the states of Arizona and California in late 1973.[4] All the victims were shot, strangled, or stabbed to death, and the majority of the murders were committed in the commission of robberies or for the purpose of eyewitness elimination.

Gretzler and Steelman were tried separately and convicted for eleven of these murders in 1974 and 1975. Both were sentenced to death for two murders committed in Arizona; each received sentences of life imprisonment relating to nine murders committed in Victor, California, in November 1973.[5]

Gretzler was executed by lethal injection at Florence State Prison in June 1998, while Steelman died of cirrhosis in August 1986 while incarcerated on death row at this facility.

The saga of the murders committed by Gretzler and Steelman have been referred to by contemporary reporters and a documentary director as the Greatest Murder Story Never Told.[6]

Early lives

[edit]Douglas Gretzler

[edit]Douglas Edward Gretzler was born on May 21, 1951, in the Bronx, New York, the second of four children born to Norton Tillotson Gretzler and his wife, Janet (née Bassett).[7] His father served as President of the Tuckahoe School District, and his mother was a homemaker.[8] In the early 1950s, the Gretzlers moved to the working class suburb of Tuckahoe, where they were regarded as upstanding residents.

The childhood of the younger Gretzler children was marred with friction. Although their father provided for his family, he was a strict disciplinarian who commanded obedience and academic achievement from his children, often subjecting them to physical and mental punishment for any failure or disobedience. Gretzler himself later recollected that although all four siblings endured harsh treatment from their father, the oldest child, Mark, was by far his father's favorite. He and his younger sisters, Joanne and Dianne, were frequently compared unfavorably with Mark; an academically achieving and popular student and often in his presence. By contrast, Gretzler was an unmotivated student who typically achieved C or D grades and performed only moderately as a Boy Scout.[9] On one occasion when Gretzler was ten, he received a good grade at school and ran home to show his father his report card. In response, his father tossed the report card aside, telling his son he expected him to do better.[10]

Although Gretzler repeatedly attempted to please his father as a young child, by the time he was eleven, he had stopped attempting to appease his father; instead seeking avenues to spite him and frequently pursuing leisure activities outside the home or playing his drums in the family basement. By 1966, Gretzler had begun smoking marijuana. His father soon discovered his recreational usage of the drug and attributed his usage of marijuana to his lackadaisical attitude toward his studies. A heated argument ensued which culminated Gretzler's father grabbing him by the collar and pushing him against a bedroom partition, causing the two to fall onto the bathroom floor. According to Gretzler, following his father's discovery of his usage of marijuana, he never failed to remind him of his "utter disappointment" in him, and although his parents arranged weekly family counseling sessions in efforts to improve family relations, the sessions yielded little progress.[11][n 1]

On August 16, 1966, the oldest of the Gretzler children, Mark, committed suicide by shooting himself in the head in his bedroom at the age of 17. His suicide came just days after his father discovered he had stolen upcoming examination papers and handed copies of the answers to other students as a prank, resulting in the school banning him from all senior year activities. His suicide note offered no explanation for choosing to end his life, but simply thanked an aunt for lending him the gun.[13] Several months later, Gretzler's father—intoxicated at the time—emerged from the family basement with a bottle of liquor. He approached his younger son to lament why it had to be Mark who had killed himself and not him.

Adolescence

[edit]Two years after his brother's suicide, Gretzler began extending his drug habit by taking narcotics such as mescaline and LSD, as a result of which his relationship with his father further deteriorated.[11] He attended Tuckahoe High School, where he earned the nickname "Lamby" among his peers. Gretzler was a member of the school football, baseball and basketball teams, but was considered somewhat average in each of these sports. His primary extracurricular interest in his teens was drumming.[14]

While Gretzler was not popular at school, his friends and acquaintances later spoke well of him. After graduating in 1969, Gretzler chose not to continue his education; instead deciding to become an auto mechanic. He worked for several months in a local car service.

The following year, Gretzler left New York and relocated to Florida, where he met a young woman named Judith Eyl, who hailed from Manhattan. The couple began dating, and shortly thereafter announced their engagement.[14]

Marriage

[edit]Shortly after their February 1970 marriage in Miami-Dade County, Florida, the Gretzlers returned to the Bronx, where they bought an apartment. However, although Gretzler held a variety of jobs, he invariably left his employment of his own volition after a matter of days or weeks—frequently leading to arguments with his wife, who worked full-time in a local bank. In 1972, Judith gave birth to their daughter, Jessica. Initially, Gretzler relished his role as a father, although he soon began to tire of the continuous responsibility; however, he was never harsh or directly neglectful to the child, instead opting to leave her in the care of his wife as he spent increased amounts of time away from home. The two began to experience increased financial difficulties and Gretzler began committing petty crime, although he was never arrested for these acts.[15]

Via a wealthy relative, Gretzler inherited a generous trust fund of several thousand dollars on his 21st birthday; he spent the majority of this inheritance on a 1967 MGB sports car and improvements to the vehicle and little, if any, on his wife and child.[15]

In the fall of 1972, Gretzler obtained employment in a Tuckahoe concrete factory. He held this job for a few months although on December 26—in part due to his worsening financial status and in part to shirk from his responsibilities as a husband and father—Gretzler abruptly abandoned both his job and his family altogether. He waited until his wife left the apartment with their baby before packing some belongings into a duffel bag and heading West in his MGB, with ambitions to ultimately relocate to Colorado. He arrived in Casper, Wyoming, on December 27 and lived in this city for six months—undertaking a series of low-paying jobs—before he was arrested for a minor traffic infraction and vagrancy on June 28, 1973. Approximately eight weeks later, Gretzler left Wyoming and drove to Denver.[14]

Willie Steelman

[edit]Willie Luther "Bill" Steelman was born on March 21, 1945, in San Joaquin County, California, the youngest of three children born to Lester Steelman and his wife, Ethel (née Hogan).[16]

The Steelman family had emigrated to California from Oklahoma in 1935, where Lester initially obtained work as a foreman at a San Joaquin farm. The family had little money, but were close-knit. As both parents worked to provide for their children, the responsibility for raising Steelman was largely delegated to his 14-year-old sister, Frances.[17]

Steelman spent his childhood and adolescence in Lodi, where he attended the Lodi High School. During his school years, Steelman was not particularly popular with his peers and was considered a social outcast, but was not bullied by other students. When Steelman was 13, his father died. Shortly thereafter, Steelman dropped out of school and began committing petty crime. Despite his mother's efforts, he refused to either recommit to his studies or find employment—frequently threatening his mother if she attempted to persuade him to commit to either. One year later, his mother remarried. She remained close to her youngest son, but frequently lamented his lackadaisical and recidivistic lifestyle, often comparing him unfavorably with his brother, Gary.[14]

Adolescence

[edit]In March 1962, Steelman's mother and stepfather persuaded him to enlist in the United States Navy; this enlistment lasted only a few months before his service was terminated. The following fall, Steelman relocated to Denver to live with his sister, although Frances soon evicted him from her home due to his unruly and threatening behavior toward her and her children. He returned to California to live with his mother.[18]

In January 1965, Steelman was convicted of three counts of forgery and involving a minor in a crime; he was placed in the custody of the California Youth Authority, who in turn sent him to the Pine Grove Work Camp, where he remained for seven months.[14][n 2]

Marriages

[edit]Following his release, Steelman obtained employment as a field hand. Shortly thereafter, he encountered a 15-year-old girl, whom he later married, with the ceremony conducted in Reno, Nevada. He soon quit his job, and the couple moved into his mother's home. In December 1965, a warrant was issued for Steelman's arrest pertaining to cashing stolen checks; he was arrested in early January the following year and remanded in custody at Stockton County Jail, where he attempted suicide. Days later, his wife's parents annulled their marriage.

In February 1966, Steelman was transferred to the Stockton State Hospital.[19] Classified as mentally ill, he was later transferred to the Atascadero State Hospital, where his "remarkable progress" saw him returned to Stockton State Hospital after several months. He was later sentenced to 14 months' imprisonment for his second forgery conviction, to be served at the California Men's Colony (CMC), where he proved to be a model inmate.[20]

Steelman was granted parole after serving just two months' imprisonment at the CMC; he was released on September 16, 1968, and returned to Lodi, obtaining employment as a shipping clerk and, according to his sister, informed many individuals he had "turned [his] life around". Three months later, he was arrested for supplying LSD to two 16-year-old girls. For this, he was sentenced to 43 days' imprisonment and fined $625. While incarcerated, he became acquainted with a young woman named Kathy Stone. He moved into Stone's house shortly after his release in the spring of 1969. Via Stone, Steelman became acquainted to a young woman named Denise Machell. The two wed in June 1969, relocating to Sacramento and, later, Mountain View.[14]

Throughout 1970 and 1971, Steelman was frequently arrested for a variety of offenses, although on each occasion, the charges were either dropped, or he was given a small fine. By 1972, his drug dependency had increased. He became an orderly at the Vista Ray Convalescent Hospital in Lodi, earning $320 a month, but lost this job for forging prescriptions. Disgusted with Steelman's refusal to improve his lifestyle,[21] his wife left him on New Year's Day 1973—informing him she was no longer prepared to excuse and forgive his behavior and of her frustration with their constantly being broke and evicted in addition to her paychecks consistently financing his heroin addiction.[22]

Acquaintance

[edit]In August 1973, Steelman traveled to Colorado, ostensibly to briefly visit his sister. Although Frances initially welcomed her brother into her home, he soon outstayed his welcome, but refused to leave her household—remaining in an unfurnished area of the house and refusing to pay rent or find employment. Although Frances resented her brother's freeloading off her, and his refusal to return to California, Steelman's oldest niece, Terry Morgan, enjoyed her uncle's company. Via Terry, Steelman became acquainted with a 17-year-old named Marsha Renslow. She was one of many youngsters who became impressed with Steelman's outlandish stories of bravado and crime. The following month, Gretzler met Steelman at his sister's home. The two initially became acquainted via Renslow, who asked the pair to steal motorcycle parts for her one evening in late September.[23]

Although Gretzler had initially arrived in Denver to seek enough work to maintain his vehicle and feed his drug habit, he and Steelman soon became close friends, although Gretzler always considered himself the follower of the two.[24] The pair frequently discussed their mutual desire to obtain quick cash via illicit means, with Steelman also teaching Gretzler how to snatch purses and checkbooks. Shortly thereafter, the two duped a teenage boy into providing them with a shotgun, and the two began devising ways of committing more serious crimes without being caught. They continued these discussions after Frances abandoned her home on September 30—just hours after Steelman had stolen her purse—and moved with her children into a nearby apartment, informing Steelman the house was to be repossessed in the coming days.[23]

Relocation to Arizona

[edit]Within days of Frances and her children leaving her home, Steelman announced to Gretzler and Renslow his decision to relocate from Denver to "someplace warmer, maybe Phoenix". Gretzler agreed to accompany him. Upon hearing this, Renslow asked if she could accompany the two, hoping to become reacquainted with a 21-year-old acquaintance named Katherine Mestites, with whom she was infatuated.[n 3] The two agreed to her request, and the trio drove from Denver to Phoenix on October 9. En route, they stopped for one night in a motel; the following evening, Gretzler accidentally discharged a firearm through a window of the motel, resulting in the three spending the night of October 10 in Gretzler's car at a nearby roadside.[26]

By October 13, the trio had driven to the town of Globe, where Steelman robbed a nude sunbathing couple of $5 at gunpoint. Hours later, close to Tempe, the trio picked up a hitchhiker, whom they drove to a secluded orange grove, stripped, pistol-whipped, and robbed.[27] The ring stolen from this hitchhiker netted the trio $60 at a Phoenix pawnshop when they arrived in the city that evening.[14]

The trio spent the night of October 13 at the Stone Motel, resolving to drive the following morning to the address of the man whom Mestites had relocated to Phoenix with: Kenneth Unrein (21), whom Renslow knew through maintaining correspondence with Mestites lived on 18th Street.[28]

Phoenix, Arizona

[edit]On the morning of October 14, the trio arrived at Unrein's address, only to learn Mestites and Unrein had recently separated. At Renslow's request, Unrein provided the trio with the Apache Junction trailer park residence of Katherine Mestites, adding she now lived with a 19-year-old named Robert Robbins.[14][n 4]

Intentionally or otherwise, Unrein provided the incorrect address. Two days later—again out of cash and furious at being lied to—Steelman decided to return to Unrein's address. On this occasion, Unrein was in the presence of 19-year-old Michael Adshade. At gunpoint, the two men were forced to drive to Mestites' apartment, where all consumed alcohol and drugs before Unrein and Adshade discreetly exited the residence and returned to their home. In their absence, Mestites divulged to her guests the details of the physical assault she had endured at Unrein's hands two months previous. Robbins then drove Gretzler and Steelman back to their motel. Mestites and Renslow remained in each other's company at Apache Junction for several days, although Renslow never mustered the courage to inform Mestites of her love for her. On October 22—having neither seen or heard from either Steelman or Gretzler for six days—Mestites purchased a plane ticket for Renslow to return to Denver.[30]

Murders and abductions

[edit]Unrein and Adshade

[edit]On October 17, 1973, Gretzler and Steelman returned to Unrein's address. Both Unrein and Adshade were forced at gunpoint into Unrein's Volkswagen van. Upon Steelman's instructions, the four drove to California.[31] Neither Unrein or Adshade were bound, although Gretzler and Steelman alternated between driving and sitting in the passenger seat pointing a gun at the two.[n 5] By the following morning, they had reached Oakdale, where Steelman purchased beverages for all.[32]

After driving aimlessly for several hours, Steelman ordered Gretzler to park the van close to Littlejohn Creek in Knights Ferry, where both captives were ordered out of the van and told to walk down a creek bed.[33] At this point, one of the two captives asked, "What's gonna happen, man?" Both were then bound with microphone cord and rope before Steelman informed them that he and Gretzler were to abandon them, adding both should wait one hour before attempting to free themselves.[34] Minutes later, the two returned to the creek. Steelman then partially strangled Unrein before stabbing him to death, then walked toward Gretzler to assist him in strangling and stabbing Adshade. The victims were then stripped naked before their bodies were concealed beneath bushes.[35]

James Fulkerson and Eileen Hallock

[edit]The following morning, Gretzler and Steelman visited an acquaintance of Steelman's in the town of Clements. By October 20, Unrein's van had broken down close to California State Route 1.[36] Minutes later, they stopped a young couple near Petaluma. Both were ordered to drive the two to Santa Clara, although the driver was ordered to stop close to the town of Marshall. The male hostage, James Fulkerson, was then bound and a gun placed against his head. In response, Fulkerson referred to his companion by name, stating: "I know I don't have much say in this, but please don't hurt Eileen, okay? Please don't hurt her."[37] This statement unnerved Steelman, who untied the young man and dragged him to his feet, informing him he had had "every intention of blowing your fucking head off". One hour later, with the male hostage in the trunk of his car, Steelman attempted to rape Hallock, but was unable to sustain an erection. The couple were robbed, then released in Mountain View the following morning after Gretzler and Steelman stole a brown Ford sedan from a parking lot.[38]

Loughran

[edit]Concerned both that Robbins and Mestites could ultimately link them to the disappearances of Unrein and Adshade, and aware the two teenagers they had released would soon inform police of their ordeal, Gretzler and Steelman decided to return to Phoenix.[39] En route to Arizona, on October 21, the two picked up an 18-year-old hitchhiker named Steven Allan Loughran close to Monterey Bay. Loughran agreed to accompany the two to Arizona, also purchasing gasoline en route.[40]

Upon their arrival at Mestites' address, Steelman was informed Renslow had returned to Denver; he also introduced Loughran as a friend from California.[41] The five spent the evening and early hours drinking, smoking, and taking drugs. By the early hours of October 23, Steelman had become resentful of Mestites' discussions relating to topics such as white magic, astrology and the concept of reincarnation. He had also begun to resent Loughran's discussion of sports-related topics.[42]

On the afternoon of October 23, Robbins drove Mestites to work at the Playful Kitten massage parlor. In their absence, Steelman initiated a fight with Loughran, although Loughran—approximately 6 feet 1 inch (1.85 m) tall and weighing 180 pounds—easily won this confrontation. In response, Steelman retrieved his shotgun and a sleeping bag, ordering the teenager out of the apartment as Gretzler followed, carrying the sleeping bag. The trio drove to a deserted gully close to the Superstition Mountains, where Steelman ordered Loughran out of the car, to hand over his wallet and then crawl inside the sleeping bag. Steelman then shot the teenager in the head; the two then returned to the trailer. Neither Robbins or Mestites inquired as to Loughran's whereabouts.[43]

Mestites and Robbins

[edit]On the afternoon of October 24, Steelman convinced Gretzler the two should murder Robbins. This decision was partly due to fear the teenager suspected their involvement in the disappearances of Unrein and Adshade and also his subservient lifestyle with Mestites. The two devised a plan to murder the teenager while Mestites was at work later that day. According to Gretzler, "after sundown" that evening, he strangled Robbins from behind with an electrical cord as the teenager entered the living room of his apartment. The two then shot him once in the head to ensure his death, then hid his corpse beneath a mattress in his bedroom. Hours later, Steelman drove Mestites back to the trailer from her place of work, explaining he had driven Robbins "out of town for a few days".

The following morning, the trio drove to a local store in Robbins' Chevrolet convertible as Mestites remarked of her relief "Ken and Bob" were "out of [her] life", and her need to "do some coke" that afternoon prior to conducting a reading to direct her future. Although Steelman attempted to persuade Mestites to go to work at the massage parlor that evening in order that he and Gretzler could dispose of Robbins' body, she refused.[44] Shortly after dusk, Steelman shot Mestites once in the head from behind as she kneeled and conducted a séance at a private altar she had constructed. Their bodies were discovered on October 28.[14]

Suspects' identification

[edit]Within 24 hours of their murders, friends and neighbors of Mestites and Robbins had alerted authorities to their disappearance. Through interviewing local residents following the October 28 discovery of their bodies,[45] investigators learned that two men named "Bill and Doug" had recently stayed at the trailer with the victims, having left the residence in the early hours of October 26, and that a young girl named "Marsha, from Denver" had also stayed at the trailer until approximately one week prior. One eyewitness, Monique Jered, informed police "Bill" had claimed to hail from California, whereas "Doug" had a notable New York accent. Both had stated their intention to travel to San Francisco. By October 31, police had determined Marsha was one Marsha Renslow; she initially refused to cooperate, but when shown Polaroid crime scene photographs of the bloated bodies of Robbins and Mestites, Renslow agreed to cooperate, naming "Bill" as Willie Steelman, and although not positive as to "Doug's" surname, stated his surname was possibly "Gritzler". The information provided by Renslow included details of robberies and carjackings the pair had committed and paying for motel rooms with stolen checks between October 9 and 16; this information was soon followed by the discovery of a motel receipt dated October 16 listing Gretzler's name and his address in the Bronx. This information proved sufficient to issue warrants for the suspects' arrest on suspicion of robbery and fraud on November 1.[46]

Hours after police interviewed Renslow for the second time on November 1, Arizona investigators received a teletype from their California counterparts informing them they had traced an abandoned green Volkswagen van linked to the October 20 kidnapping and robbery of a teenage couple to a missing Arizonian named Kenneth Unrein, adding the teenagers had named their abductors as "Bill" and "Doug".[46]

Sierra

[edit]Within hours of Mestites' murder, Steelman persuaded Gretzler to accompany him to Tucson. The two left Apache Junction in Robbins' Chevrolet in the early hours of October 26, but abandoned the vehicle on Van Buren Street hours later.[n 6] The two then traveled to Tucson via bus, purchasing the tickets with money stolen from Mestites. They arrived in the city on October 27, residing in a cheap boarding house on 4th Avenue. The two remained at this boarding house until November 1, having by this date become acquainted with a young woman named Joanne McPeek—the younger sister of their landlady, Susan Harlan.[48]

Late in the evening of November 1, Gretzler and Steelman decided to steal a car to flee the city. Shortly after they began hitchhiking close to the University of Arizona, the two approached a Dodge Charger driven by 19-year-old Gilbert Rodriguez Sierra as he slowed the vehicle close to a stoplight, with Steelman thanking him for stopping before stating, "We need a ride. Need a car—your car!" Sierra was then ordered into the back seat at gunpoint as Gretzler began to drive. As had been the case with the two teenagers they had held hostage at gunpoint, then released, on October 20, Steelman claimed to be a notorious hitman on the run, having "just wasted a cop". It is unknown if Sierra believed these boasts as according to Gretzler, he simply stared blankly at Steelman, muttering a brief sentence in Spanish as opposed to English for the first time.[49]

Steelman then forced Sierra into the trunk of his car before the two returned to the Tucson apartment of Joanne McPeek and her partner, Michael Marsh, which they had left hours earlier; McPeek and Marsh were persuaded to accompany the two to purchase hard drugs, with Steelman adding, "We got a dude in the trunk, a narc." When McPeek stated she didn't believe him, Steelman rummaged through the glove box for identification, before shouting to the rear, "Hey! Your name Gilbert?" to which Sierra replied, "Yeah!" Steelman then asked Marsh for directions to the desert, adding "I'm gonna kill this sonofabitch!"[50]

Shortly thereafter, in the presence of these individuals at a deserted canyon close to Gates Pass,[51] Steelman dragged Sierra from the trunk at gunpoint, forced him to hand over his T-shirt, then ordered him to his knees as he accused him of being a "pig" and a "narc".[52] Steelman twice attempted to shoot Sierra, although on each occasion, the pistol misfired as he had covered the firearm with Sierra's T-shirt. As Sierra desperately tried to run, Steelman removed the T-shirt and shot him once in the back, causing him to collapse to his knees and fall into an opuntia cactus, then down a small ravine. Steelman then ran down the ravine and shot Sierra in the face and temple at close range as Gretzler laughed. The four then returned to Tucson and purchased amphetamines from a local drug dealer before spending the remainder of the night at a Mabel Street drug den with a teenager named Donald Scott, whom they first encountered at this address.[53]

After wiping all fingerprints from Sierra's car the following day, Gretzler and Steelman abandoned the vehicle in a parking lot. Sierra's body was discovered approximately twelve hours after his murder. He was formally identified on November 5.[14]

Vincent Armstrong

[edit]On the morning of November 3, a young student named Vincent Armstrong observed the two hitchhiking close to the site of Sierra's abduction. He stopped to offer the two a lift,[54] although shortly thereafter, Steelman pressed a gun against his torso, ordering him to continue driving. When Armstrong began panicking, Steelman punched him before ordering him to "pull over, then" close to an intersection. Armstrong then climbed into the passenger seat of his Pontiac Firebird as Gretzler took control of the vehicle. Moments after Gretzler took control of the vehicle, Armstrong threw himself head first from the passenger seat to the pavement—sustaining severe bruising and abrasions and shattering his glasses—as Gretzler performed a U-turn, directing the vehicle at him. Armstrong then scrambled over a low wall and ran into the grounds of a nearby church as Gretzler sped from the scene.[51]

Armstrong reached the home of an acquaintance, where he reported his ordeal to the Tucson Police Department, who later recovered his broken glasses at the location of his escape. He was driven to a nearby hospital and given appropriate medical attention. Armstrong later assisted police in creating identikit drawings of his assailants.[26]

Michael and Patricia Sandberg

[edit]After Armstrong had jumped from his vehicle, Gretzler and Steelman drove in an aimless manner around Tucson until they drove by a condominium in the Villa Paraiso complex close to Vine Street.[55] Outside this address, they observed a 28-year-old former Marine captain and student teacher named Michael Sandberg washing his Datsun car.[56] Steelman threatened Sandberg with his gun before the pair forced him to take them to his condominium, where his 32-year-old wife, Patricia, encountered the trio as she prepared food in the kitchen. Gretzler pressed a knife to her neck as Steelman informed the couple they were to remain hostages until after dusk, after which they would be left unharmed.[57]

At Michael's request, Patricia was given Valium to help ease her nerves. She then prepared a sandwich for Gretzler before Steelman decided the two should adjust their appearances. Gretzler then dyed his blond hair brown before Steelman shaved off his mustache and attempted to disguise a black eye he had recently received with Patricia's cosmetics. Both then changed into clean clothing from Michael's closet before Gretzler bound Patricia's arms behind her back with twine and ordered her sit on the floor of the bathroom.[58] Michael was then forced to lie face-down on the couple's bed before his ankles and neck were bound in a manner which ensured he could not move his ankles without choking himself.[59]

Minutes later, Patricia was dragged from the bathroom to the couch where she was further bound before Gretzler walked into the bedroom and shot Michael in the head; he then shot Patricia once in the head through a cushion Steelman had placed over her skull to muffle the sound of the discharge.[60] Steelman then fired four further rounds into her head. Noting Patricia was still alive, Steelman repeatedly bludgeoned her about the head with a golf club until her twitching ceased.[11] After destroying any potential incriminating evidence at the crime scene, Gretzler and Steelman packed some of Michael's clothes into a suitcase before stealing the Sandbergs' credit cards, a camera and other items of material value from the house. The two then fled the scene in the Sandbergs' Datsun, leaving Armstrong's Firebird parked beneath a canopy close to the condominium.[61]

November 4-6, 1973

[edit]Immediately after leaving the Sandberg residence, the two returned to the Mabel Street drug den they had left that morning. Only Donald Scott was still at this address; he agreed to their offer to accompany them to California. The trio drove to a nearby motel in Stanfield, Arizona, where they spent the night of November 3-4. The following evening, they stopped overnight in another motel, again signing the register as Michael Sandberg and again paying for their room with a forged check taken from the Sandbergs' residence.

By the afternoon of November 5, the three had reached Pine Valley, California, where Gretzler and Steelman agreed to Scott's request to discontinue riding with them, allowing him to exit the vehicle close to Interstate 8. They then continued driving in the direction of Victor, California,[62][n 7] with Steelman talking increasingly frequently of robbing the owners of the downtown United Market,[64] assuring Gretzler the owners, Walter and Joanne Parkin (with whom he had previously had a heated confrontation), were wealthy. He also explained the family resided in a rural ranch house surrounded by vineyards,[65] and anticipated a robbery of the Parkins' Orchard Road household and their supermarket would net the pair anything up to $20,000.[66]

Parkin-Earl-Lang massacre

[edit]By the afternoon of November 6, 1973, the pair had returned to Steelman's hometown of Lodi,[67] where they slept at the home of an acquaintance until shortly after 5:00 p.m. before Steelman persuaded a friend named Duff Nunley to telephone his 17-year-old nephew, Gary Steelman Jr.; Nunley convinced Gary his uncle's life was in danger and persuaded him to hand Steelman his father's Derringer handgun without his father's knowledge. The two thanked Steelman's acquaintance and nephew for the firearm, then informed them they were leaving the state.[n 8] Gretzler and Steelman then drove to the United Market at closing time, expecting to find Walter Parkin alone at the premises, only to discover the building already closed; they then drove two miles toward Orchard Road.[14]

At the time of their arrival, the Parkins were not home; the couple's two children, 9-year-old Robert and his 11-year-old sister, Lisa, were being babysat by 18-year-old Debra Earl and her 15-year-old brother, Richard. The two entered the property by Steelman briefly deceiving Debra into believing they owed the Parkins money to lower her guard before pushing past her and immediately threatening the teenagers at gunpoint, with Steelman shouting: "Now listen! We're only here for [Walter], so both of you stay cool and nobody is gonna get hurt! That understood?" As Richard stood in shock, Debra comforted the Parkin children as she wept, explaining Walter and Joanne were bowling and wouldn't return for "a couple of hours." All four were then forced to sit on the sofa.[69]

Prior to the two entering the house, Debra had phoned her father, Richard Sr., in distress; he sped to the Parkin residence, where he too was held at gunpoint as Debra again burst into tears, shouting "Oh Daddy!"[70] Upon learning Richard Sr. had told his wife, Wanda, to contact police if he was "not back [home] in fifteen minutes", Steelman ordered Gretzler to watch the child and teenage hostages at gunpoint as he ordered Richard Sr. at gunpoint to retrieve Wanda from their home, adding he should "dust [the hostages]" if he, Richard Sr. and Wanda were not back at the Parkin residence in twenty minutes. Minutes later, Steelman returned to the Parkin residence with Richard Sr. and Wanda Earl.[71][n 9]

At approximately 9:25 p.m. Debra's fiancée, 20-year-old Mark Lang, arrived at the Parkin residence by prearrangement to drive Debra and her brother home. He was also taken hostage at gunpoint, and allowed to comfort his weeping girlfriend.[72]

Walter and Joanne Parkin returned to their home at approximately 10:45 p.m. All adult hostages were then forced to hand over all the money and jewelry in their possession before, at Joanne's pleading, she was allowed to put her two children to bed in the master bedroom—pleading with the two to go to sleep in order that they become oblivious to the ongoing ordeal.[72] Steelman then ordered the adult and teenage hostages, except Walter, into the bathroom, where Gretzler bound the hostages with nylon cord he had retrieved from the Sandbergs' vehicle. The male hostages were bound first, before Wanda, then Debra, and finally Joanne. All were ordered to sit in a semi-circle inside a large walk-in closet in the master bedroom with Gretzler observing the hostages as Steelman forced Walter to drive to the United Market to retrieve money from a floor safe he knew the Parkins kept at the supermarket.[73] This robbery netted approximately $4,000 (the equivalent of about $27,660 as of 2024[update]). The two then returned to the Parkin residence, where Walter was also bound and placed in the walk-in closet.[74] All adult hostages were then bound together by their ankles, then gagged.[14]

According to Gretzler, once the two had wiped their fingerprints from surfaces they had touched, he exclaimed to Steelman, "Listen, why don't we split? We got what we came here for. Let's just get outta here!" Steelman refused, stating: "I said all along, no witnesses. I know you remember me sayin' it."[75]

Gretzler then shot and killed the two Parkin children in the master bedroom.[76] Each was shot once between the eyes as they slept. The two then opened the walk-in closet, where the remaining seven hostages had begun desperately screaming, writhing, and contorting. Richard Earl Sr. was then shot and wounded in the temple; Gretzler then shot Walter Parkin, Richard Earl Jr., Wanda Earl, Debra Earl, and Joanne Parkin.[77] After reloading his gun, Gretzler then shot Mark Lang to death before Steelman fatally shot Richard Sr. before repeatedly firing into the bodies of all deceased and dying hostages inside the walk-in closet.[78]

Gretzler then consumed a slice of chocolate birthday cake and a bottle of wine found in the family kitchen as Steelman drank from a bottle of Seagrams as he searched for further money and valuables within the residence. The two then left the Parkin household at approximately 1:20 a.m.[79][80] One hour later, they checked into a Holiday Inn under the alias of W. J. Siems.[81]

Discoveries

[edit]At 3:00 a.m., a young house guest and employee of the Parkins, 18-year-old Carol Jenkins, returned to the Parkin residence.[82] Although she noted two lights remained on which should have been turned off, she decided not to investigate, for fear of waking the family. Jenkins immediately fell asleep in her bed.[83]

Four hours later, two friends of Mark Lang—having been alerted to his disappearance by his mother—discovered his Chevrolet Impala parked outside the Parkin residence.[84] When the two friends knocked on the door of the property at approximately 7:03 a.m., Jenkins groggily agreed to ask the Parkins if they knew of Lang's whereabouts—believing the couple to still be asleep in the master bedroom. Jenkins entered this bedroom as Lang's friends remained in the hallway.[63]

One of the first responders to the scene would later state the first sight he observed as he arrived at Orchard Road was two distraught males in their late teens or early twenties themselves chasing and attempting to catch and comfort a young woman "running in and out of the house", frantically flailing and screaming "Oh my God!" The officers entered the residence to discover the bodies of the two Parkin children in the master bedroom.[81]

Upon learning the children's babysitter, her boyfriend, and younger brother were unaccounted for, investigators drove to the Earl residence at 7:40 a.m., only to discover the house unoccupied, and a loaded .410 shotgun upon Richard Earl Jr.'s bed.[n 10] Upon returning to Orchard Road, a sergeant named Steven Mello searched a hallway leading to the family bathroom, where he discovered the remaining seven casualties inside the walk-in closet.[81]

Investigation

[edit]While investigating the murders of the Parkin and Earl families and Mark Lang, police found several witnesses who gave a description of the two criminals, including the owners of the motel in which the two had spent the night of November 5, and who had paid for the room with a dud check in the name of one Michael B. Sandberg. The license plate of the cream Datsun vehicle had been an Arizona plate, number RWS 563. From this, the California State Department contacted their colleagues in Arizona, who determined that the car was registered to one Michael Bruce Sandberg, who resided in the Villa Paraiso apartment complex in Tucson.[85][n 11]

Just hours after the discovery of the nine victims at Orchard Road, a Tucson investigator named David Arrelanes secured updated arrest warrants for Gretzler and Steelman in relation to the Mestites and Robbins murders, with bail for the fugitives set at $220,000 each. Arrelanes returned to his office to receive a teletype notifying his department of the nine homicides in San Joaquin County. He immediately contacted his California counterparts, whom he updated on his department's manhunt for Gretzler and Steelman in relation to two recent murders in Phoenix, and who he stated his department had "every reason to believe" may have returned to Steelman's home turf in Lodi. Arrelanes provided his counterparts with a recent booking photo of Steelman and copies of the existing arrest warrants.[86] At a press conference held late in the evening of November 7, San Joaquin County Sheriff Michael Canlis informed the media the chief suspect in the Victor murders was one Willie Steelman, adding his department had reason to believe he was also responsible for "two recent killings in Phoenix." All media personnel were provided with copies of the photograph provided by Arrelanes.[40]

On November 8, California investigators were also contacted by an individual who had been in their company for a brief period of time the previous afternoon—confirming Gretzler and Steelman had been in Lodi immediately prior to the murders at Orchard Road.[87] The same day, Donald Scott also contacted authorities to state that Gretzler and Steelman could be involved in the killings, having discussed the imminent robbery of a Victor supermarket belonging to a "Wally Parkin" as he had traveled with the two just days previous. Arrest warrants were also issued for the two men in California, and their names—accompanied by a recent mug shot of Steelman—were published in the Sacramento Union on the morning November 8, and the Sacramento Bee that afternoon.[80]

Arrest

[edit]After leaving the Holiday Inn in the late morning of November 7, Gretzler and Steelman drove north for several hours, with agreed plans to ultimately reach Nevada before Steelman decided they should "lay low" for a few days before attempting to cross state lines. The two parked the Sandbergs' Datsun in a multistorey car park before purchasing new clothes and checking into the nearby Clunie Hotel in Sacramento, paying in advance for three days. Steelman signed the register as Will Simen, whereas Gretzler signed using his real name.[88]

On the morning of November 8, Steelman purchased a copy of the Sacramento Bee from the hotel lobby, only to observe his mug shot on the front page and to read he and Gretzler were the prime suspects in eleven homicides. This revelation unnerved Steelman, who decided their best option was to flee California immediately. Realizing returning to the Sandbergs' Datsun was too risky, Steelman decided the two should try and convince a young female acquaintance named Melinda Ann Kashula—whom he had encountered the previous afternoon at a massage parlor—to accompany the two to Florida.[82]

As the two exited the hotel, a clerk named William Reger recognized Steelman. Reger waited until the two had exited the lobby before discreetly informing the police of their whereabouts. Within minutes, numerous armed police had converged on the hotel.[89]

At Kashula's apartment, the young woman feigned interest in Steelman's offer before declining to drive the two to Florida. She then indicated she may know of alternate accommodation for the two in Davis. Minutes later, Steelman encouraged Gretzler to return to the Clunie Hotel via taxi to retrieve their belongings, adding his own picture had been published on the front page of the Sacramento Bee, but that the media were unaware of his own physical appearance.[80]

Gretzler

[edit]Gretzler was observed entering the hotel and entering an elevator bound for his room on the third floor. Police sealed the second floor of the premises and positioned sharpshooters to cover every escape serving the third floor.[82]

As he attempted to enter his room, Gretzler overheard an officer talking in hushed tones on the telephone behind the door. He fled to the fourth floor in a vain attempt to escape from the building—concealing the Derringer in a small portal above a doorway—before descending to the second floor, raising his arms and waiting for his inevitable arrest.[90]

The time of Gretzler's arrest was 10:04 a.m. As Gretzler was searched for weapons, he informed police, "Man, I'm glad this is over. I've seen enough killing, and man, I don't wanna see any more." He then provided police with the address where Steelman could be located, adding Steelman was in the company of a young woman, that he was armed, and had sworn never to be "taken alive" if arrest was impending.[80][82]

Steelman

[edit]At 10:50 a.m., the first of over 70 armed police officers arrived outside Kashula's apartment. Their presence was quickly noticed by Kashula, who became hysterical as a police chief shouted through a bullhorn: "Willie Steelman, this is going to be your last chance to give yourself up peacefully." Although Steelman heard this message, he initially refused to surrender; first claiming to Kashula he was the victim of mistaken identity as he threatened to commit suicide before Kashula dissuaded him from doing so, then agreeing to surrender but only if the media were present outside the apartment to record his arrest and after the police chief persuaded a disc jockey to announce live on a local rock radio station that he and Kashula would not be harmed if they exited the apartment separately, with their hands aloft. The chief negotiator agreed to these requests.[65]

Two minutes after the terms of Steelman's surrender were broadcast across the airwaves of KZAP, police fired a single tear gas canister into the apartment as Kashula argued with Steelman to honor his promise to surrender.[65] In response, Steelman shouted his intentions to surrender, but only after Kashula had been allowed to safely exit her apartment. The two exited the apartment separately after Kashula tossed Steelman's firearm onto the lawn. Steelman was then manacled and placed in a police car as he shouted, "Guess I'm going back to Stockton!"[80]

Evidence retrieval

[edit]Much of the money stolen from the United Market was discovered in the suspects' possession at the time of their arrest; this money was traced to a batch of notes issued to Walter Parkin shortly before the Orchard Road murders. In addition, Gretzler was found to have placed the Sandbergs' door key upon his key ring.[14]

A police search of the hotel room the two had rented recovered several firearm cartridges, a Smith & Wesson .38 caliber revolver later determined via ballistic testing to have been used in numerous homicides linked to the pair,[n 12] the Sandbergs' checkbook and stolen identity cards in addition to other physical and circumstantial evidence linking the two to numerous recent crimes in both Arizona and California. Several shell casings discarded by Steelman alongside a highway following the Orchard Road murders were later recovered and forensically proven to have been discharged by the firearm in his possession at the time of his arrest.

Upon locating the Sandbergs' vehicle on the evening of November 8,[39] investigators discovered a bloodstained pair of boots and jeans and a brown grocery sack filled with numerous wallets, purses, credit cards, driving licenses and items of jewelry belonging to those murdered at the Parkin residence.[92]

Initial statements

[edit]Both Gretzler and Steelman were extensively questioned by Sacramento County investigators in relation to the Orchard Road murders before they were transferred to the custody of San Joaquin authorities on the evening of November 8.[93] The two were separately escorted to French Camp under armed guard to formally face charges pertaining to the nine murders committed in Victor. Both were held in solitary confinement at Deuel Vocational Institution, and prohibited from contact with each other.[94]

Although Steelman refused to divulge much information pertaining to the murders prior to being assigned an attorney, at which point he refused to talk with any investigators, Gretzler consented to interview requests from both Arizona and California investigators. He was initially cooperative but evasive—falsely claiming all the abductions and robberies the pair had committed in both Arizona and California over the previous three weeks had been at Steelman's behest and that Steelman had committed all the murders—but gradually revealed his culpability in several of the murders.[94][95]

Arraignment

[edit]On November 9, both defendants were arraigned upon nine counts of first degree murder, each in relation to the Orchard Road murders (a further charge of kidnapping with intent of robbery was later added on November 14). Both were assigned public defenders: Gretzler was assigned George Dedekam as his legal representative; Steelman was assigned Sam Libicki.[96] By November 10, both had confessed to 17 murders,[97] with Steelman revealing the location where they had concealed the bodies of Unrein and Adshade in addition to Loughran, whose disappearance had not been linked to the two. Loughran's body was discovered on November 10; Unrein and Adshade were recovered the following day.[98]

Formal confessions

[edit]Gretzler provided investigators with a full confession on the afternoon of November 10. He began by recounting the events at Orchard Road before outlining the previous eight murders. Gretzler claimed he had become desensitized to committing murder by gunshot in part due to the psychological trauma he had experienced in witnessing Steelman strangle and stab Unrein as he attempted to strangle Adshade, stating: "[The two] were garotted. That's the dirtiest way I know to kill somebody; that's probably why I could take so many deaths as that, because after [those two], I was steeled ... I couldn't kill mine completely dead because it made me sick and he was kicking and shuddering and blood came out of his eyes and I'm sure he was half dead, brain damage or something, so I let up and Bill came over and helped me finish it."[97]

| Victims |

| 1. Kenneth Francis Unrein (21): October 18, 1973 |

| 2. Michael Raymond Adshade (19): October 18, 1973 |

| 3. Steven Allan Loughran (18): October 23, 1973 |

| 4. Robert G. Robbins (19): October 24, 1973 |

| 5. Katherine M. Mestites (21): October 25, 1973 |

| 6. Gilbert Rodriguez Sierra (19): November 2, 1973 |

| 7. Michael Bruce Sandberg (28): November 3, 1973 |

| 8. Patricia May Sandberg (32): November 3, 1973 |

| 9. Robert Allen Parkin (9): November 7, 1973 |

| 10. Lisa Diane Parkin (11): November 7, 1973 |

| 11. Walter George Parkin (32): November 7, 1973 |

| 12. Joanne Carol Parkin (33): November 7, 1973 |

| 13. Richard Allen Earl Sr. (38): November 7, 1973 |

| 14. Wanda Jean Earl (37): November 7, 1973 |

| 15. Debra Jean Earl (18): November 7, 1973 |

| 16. Richard Allen Earl Jr. (15): November 7, 1973 |

| 17. Mark Allen Lang (20): November 7, 1973 |

Hours later, Steelman also provided investigators with a full confession. His account of the murders contained only minor discrepancies with Gretzler's. Steelman also described two further killings he claimed to have committed to investigators. According to Steelman's testimony, on October 13, 1973, after he, Gretzler and Renslow had arrived in Phoenix, he had met with a renowned drug dealer friend nicknamed "Preacher" as Gretzler and Renslow remained in their motel room.[n 13] He had returned to their motel room disheveled approximately 25 minutes later, claiming Preacher had been killed by his own brother before he and another individual named Larry had killed Preacher's brother and another man. Steelman then claimed "Larry" had taken the three bodies "to the Arizona desert" to be buried.[14] No reports of gunshots within the vicinity of the motel were reported on October 13, nor were any missing person reports on three men ever filed in the city around this date. Ultimately, investigators disregarded this account as unreliable.[99]

Diplomatic dispute

[edit]Although the state of Arizona had informed their Californian counterparts of their intentions to apply for the two to be extradited from California to first be tried for the murders of Robbins and Mestites, stating the Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure required a trial to be held within 150 days of the filing of criminal charges against the defendant(s), and thus without an extradition, the warrants issued in their state for these murders would likely have to be declared null.[100] However, California investigators ultimately decided the two would first be tried for the Orchard Road murders, and thereafter extradited to Arizona to be tried for further murders committed in their state.[101]

Indictments

[edit]On November 28, a grand jury convened to hear the evidence against Gretzler and Steelman. They deliberated for scarcely five minutes before deciding sufficient evidence existed to indict both upon nine counts of murder and one count of kidnapping in the commission of robbery. These indictments were presented to Superior Court Judge Christopher Papas.[102] Following several legal maneuvers from both defense counsels, Papas agreed to a joint requested motion for a change of venue, ruling on May 21, 1974, that the trial was to be held in Santa Rosa.[103]

Shortly prior to the commencement of their trial, on June 4, Gretzler agreed to his lawyer's advice to plead guilty to all charges; however, Steelman refused to do so.[104][n 14]

Trials

[edit]California

[edit]Gretzler and Steelman were tried jointly for the Orchard Road murders in June 1974.[106] Gretzler formally pleaded guilty to nine counts on June 4; Steelman—upon advice from his attorney—pleaded no contest to all charges in exchange for the prosecution agreeing not to pursue the charge of kidnapping against him. Sentencing was postponed until the following month.[107]

On July 8, both were sentenced to life imprisonment—Gretzler for nine counts of murder, and Steelman for nine counts of murder and five counts of robbery. Upon passing sentence, Papas described Steelman as "the architect and engineer" of the murders, and Gretzler as "a willing follower" in the commission of the crime, and recommended neither ever be freed from prison.[108][n 15] Neither showed any emotion as the verdict was announced.[107]

Two weeks after their convictions for the Orchard Road murders, then-Governor of California Ronald Reagan authorized the extradition of Gretzler and Steelman to Arizona for the murders of Michael and Patricia Sandberg and Gilbert Sierra. The prisoners were escorted to Tucson on September 17, and a gag order subsequently issued, prohibiting any pretrial publicity.[111]

Arizona

[edit]Prior to their Arizona trials, Gretzler was assigned David Hoffman as his legal representative; Steelman was assigned John Neis (later replaced by Robert Norgren). Gretzler was tried before Judge William Druke; Steelman before Judge Richard Greer.[112] Both defense attorneys filed numerous pretrial motions delaying the commencement of their clients' respective trials by several months.[113]

Although Arizona had initially planned on trying both defendants together, Druke ruled on February 10 that the defendants be tried separately.[n 16] On March 3, prosecutor David Dingeldine offered a stipulation that if he obtained a first degree murder conviction for the Sandberg murders, he would not try either defendant for the Sierra murder. This offer was accepted by both defense counsels.[61][n 17]

Steelman

[edit]Steelman was brought to trial at the Apache County Courthouse in St. Johns, Arizona, on July 10, 1975. Dingeldine delivered his opening statement to the jury on this date; outlining the events of the date of the murders of the Sandberg murders, the evidence to be presented indicating Steelman's guilt and the various prosecution witnesses to testify on behalf of the prosecution. Referring to the murders within the Villa Paraiso complex as "premeditated, brutal, execution-type" killings, Dingeldine closed his opening statement by saying the state expected the jurors to return two verdicts of guilty of first degree murder. This opening statement was followed by Norgren's argument for the defense: Norgren argued the prosecution had the duty to prove his client—and not Gretzler—had fired the fatal shots before questioning Steelman's "mental capacity or mental condition" at the time of the murders, resultant from numerous years of hard drug abuse. He then inferred the evidence would show Gretzler had bound and killed the couple before closing by stating he expected the jurors "to find Willie Steelman not guilty."[117]

The prosecution called numerous witnesses to testify as to Steelman's participation in the Sandberg murders over the following days. These included Vincent Armstrong, who testified as to his abduction and escape from his Firebird shortly before the defendant's arrival at the Villa Paraiso complex. Armstrong identified a police photograph of his vehicle as parked outside the Sandbergs' apartment. He also identified Steelman as one of his attackers, adding Steeelman had been more vocal and aggressive than Gretzler throughout his ordeal. Also to testify was Donald Scott, who outlined his brief acquaintance with Gretzler and Steelman between November 2 and 5, 1973, and an individual named James Nelson, who had observed Michael Sandberg washing his vehicle as Steelman and Gretzler had parked Armstrong's Firebird close to the Sandberg complex.[51]

The first physical evidence was introduced on July 11, when an investigator named Larry Hust formally identified a bloodstained cushion and blanket as items he had removed from the sofa upon which Patricia Sandberg's body was found, adding the cushion had evidently been used to silence the discharge from the firearm used to kill her. Hust's testimony was followed by that of the owner of the motel the defendant and Gretzler had stayed in on the night of November 3-4, a Mrs Francisco. This witness stated Steelman had paid for a room with a $5 check in Michael Sandberg's name, had signed the motel register as Michael Sandberg and had displayed a Veteran's Card issued to a Captain Sandberg as a form of identification. Francisco also formally identified Steelman as the individual who had stayed at her motel on the night in question.[118]

On July 14, an FBI fingerprint analyst testified numerous fingerprints recovered from the apartment matched Steelman. His testimony was followed by that of a firearms expert, who testified that numerous bullets recovered from the heads of both decedents had been fired by the revolver discovered in Steelman's possession at the time of his arrest. The prosecution rested their case the following day.[119]

The defense produced their first witnesses on July 17. The first witness to testify was Steelman's former wife, Denise Machell, who spoke via a 15-minute videotaped interview of herself created for the defense. Machell outlined Steelman's sudden bouts of anger throughout their marriage and his inability to recall incidents triggered by his extreme rage. Following a brief recess, Steelman then took the stand in his own defense to describe in greater detail extreme, recurring headaches his former wife had stated he had suffered following a fall outside a department store in 1972. In an apparent effort to convince the jury into believing he was insane, Steelman then launched into a tirade of outlandish claims portraying himself as a "fighter of the oppressed people" driven to violence by seeing "brothers die in the streets trying to change things" and that he had begun dropping acid to alleviate his pain caused by injustices perpetrated by the government. Steelman then claimed that he had killed Michael Sandberg due to his Marine background and being part of the "ruling class".[120]

To support their contention that Steelman was insane as outlined in the M'Naghten rules, the defense then called two experts to testify as to their belief Steelman was legally insane and unable to control his actions. The first to testify was clinical psychologist Dr. Irvin Roy, who outlined several Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale tests he had performed on Steelman, and his conclusion that although no organic brain damage was found, the tests indicated Steelman suffered from "minimal brain damage", with irritable and impulsive traits. Upon cross-examination, Roy conceded he had only performed limited testing on Steelman, and that a subject in Steelman's predicament could intentionally provide different responses to the tests conducted to influence the outcome of the tests.[117]

Roy's testimony was followed by that of psychiatrist Dr. James Peale, who also attested to his belief Steelman suffered from schizophrenia and organic brain damage, and was unable to differentiate between right and wrong. Upon cross-examination on July 18, Peale reiterated his belief to Dingeldine that Steelman was unaware of the criminality, intent, and consequences of his actions when restraining, murdering and robbing the Sandbergs before Dingeldine waved him off the stand.[118]

Three doctors testified on behalf of the prosecution as to Steelman's sanity on July 21. The first doctor to testify, Dr. Austin, testified that although suffering from an anti-social personality disorder, Steelman was sane. His testimony was followed by that of a Dr. Rogerson, who dismissed Dr. Peale's assertion Steelman's criminal behavior was a result of his drug use. The final doctor to testify, Dr. Cavanaugh, also testified to Steelman's sanity. The following day, a psychiatrist and a psychologist each testified that Steelman knew right from wrong, and the consequences of his actions. One of these experts, a Dr. Fox, also disputed the defense's contention Steelman suffered from brain damage. The state then rested its case.[118]

On July 23, both prosecution and defense attorneys delivered their closing arguments to the jury. Dingeldine argued first, recounting the evidence the state had presented and pouring scorn over the defense contention of insanity before asking the jurors to return two counts of guilty of first degree murder. Norgren then delivered the defense's closing argument, claiming the state had not proven beyond a reasonable doubt his client's guilt in the murders, or his sanity at the time of the murders. Norgren asked the jurors to either return a verdict of not guilty, or guilty or a reduced charge.

Following a brief rebuttal argument from the prosecution in which Dingeldine again outlined Steelman's culpability and the "lack of evidence" to indicate he failed to understand the difference between right and wrong, the jurors retired to consider their verdict at 2:30 p.m. At 5:15 p.m., the jurors announced their verdict: Steelman was guilty of two counts of murder, one of kidnapping (in relation to Vincent Armstrong), two counts of robbery, and one count of burglary. He was sentenced to death on August 27, plus 80 to 95 years for the kidnapping of Armstrong and the burglary and robbery of the Sandbergs.[121]

Gretzler

[edit]Gretzler's trial was held in the Federal Building in Prescott, Arizona, before Judge William Druke in October of the same year, with David Dingeldine again serving as prosecutor.[122] The process of jury selection began on October 15, 1975, and the prosecution delivered their opening statement on October 22. The first witnesses to testify on behalf of the prosecution—Vincent Armstrong and Donald Scott—did so on this date.[123]

As Gretzler had already formally confessed to the Sandbergs' murder, the strategy chosen by David Hoffman was to secure second degree murder convictions—thereby saving his client's life. He attempted to discredit Armstrong's identification of Gretzler as his assailant—portraying Steelman as the main aggressor and alleging Armstrong had been to apprehensive to obtain a clear look at Gretzler; he also referenced Scott's frequent drug usage with Gretzler in his cross-examination of the teenager in an attempt to discredit Scott's character and testimony.[124]

On October 23, Dingeldine introduced 26 Polaroid photographs into evidence, two of which were the Sandbergs' Datsun, which Donald Scott formally identified as being the vehicle he had traveled in with Gretzler and Steelman on November 3.[n 18] Other items of physical evidence the two had taken from the Sandbergs' apartment and later found in their possession were also introduced into evidence. James Nelson then testified as to observing Gretzler and Steelman following Michael Sandberg into his apartment.[126]

Against overruled objections from Gretzler's counsel, Detective Larry Bunting testified as to a recorded conversation he and a colleague had had with Gretzler on the weekend following his arrest. This recording was then played to the jury, who heard Gretzler describe the kidnapping of Armstrong and, following his escape, how he and Steelman agreed they should obtain a separate vehicle. The two then "saw a guy washing his Datsun." According to Gretzler's recorded account of the events to ensue, he had waited outside the Sandbergs' apartment for several hours before Steelman emerged with a suitcase and a change of clothing for him. He had not known of the Sandbergs' death until after his arrest. This account was later discredited by a fingerprint expert, who testified four fingerprints were recovered from a mayonnaise jar and a water glass in the Sandbergs' kitchen were a match to Gretzler.[126]

On October 28, a forensics expert testified as to the autopsies he had conducted on the Sandbergs. Although Hoffman attempted to taint the image of the victims by referencing the Sandbergs' toxicology reports, this expert explained that when a body decomposes "as much as these had", the body produces an alcohol reading. A ballistic expert then testified that the bullets recovered from the victims had been fired by the weapon recovered from Steelman at the time of his arrest.

Later the same day, the second recorded confession was introduced into evidence. On this recording—made eleven days after Gretzler's arrest[127]—he confessed to investigator Larry Hust "myself and Bill" had fired the rounds which had killed the Sandbergs. Two days later, Hoffman attempted to call Steelman to the stand, although Steelman refused to answer any questions, leading to his attorney to state to the court his client had "no intention of answering any questions".[128]

Upon the advice of his attorney (who wanted to avoid his client being subjected to cross-examination), Gretzler did not testify in his own defense; he instead read a brief statement to the court on October 30 stating he had no intention of "[hiding] behind the shield of an insanity defense" and portraying himself as a "follower" by nature and a "peaceful, law-abiding citizen" prior to meeting Steelman. He claimed to have remained outside the Sandbergs' apartment throughout the time of their murders and closed his statement by requesting the jury find him guilty, but of second degree murder. This statement was followed by testimony from Gretzler's mother and sister, who respectively described a head injury Gretzler had received in March 1969 and his "always being spaced out and confused" due to his drug usage.[129]

Hoffman introduced his final character witness on November 3. Two days later, both counsels delivered their closing arguments before the jury: Dingeldine spoke first, outlining the evidence which contradicted Gretzler's claim to have never set foot in the Sandberg residence before requesting two verdicts of guilty of first degree murder. After a brief recess, Hoffman delivered his own closing argument. He spoke for two hours, disputing much of the prosecution evidence and arguing his client's "limited participation" in murders "masterminded by Willie Steelman" only warranted verdicts of guilty of second degree murder. The jury then retired to consider their verdict; they deliberated for just over two hours before announcing they had reached their verdict: Gretzler was found guilty of two counts of first degree murder, in addition to two counts of robbery and one of kidnapping.[130]

Due to several legal maneuvers filed by his defense counsel prior to formal pre-sentencing hearings, Gretzler was sentenced to death for both murders on November 15, 1976; he was also sentenced to a concurrent sentence of 25 to 50 years for the charges of robbery, kidnapping, and burglary.[131]

Death row

[edit]Following their Arizona trials for the murders of Michael and Patricia Sandberg, both men were transferred to death row at Florence State Prison to await execution. Over the next two decades, both filed numerous appeals to overturn their sentence, with Gretzler insisting that his drug addiction and mental health were mitigating circumstances for his crimes. Steelman's attorneys appealed against his conviction on issues such as legal technicalities. All of their appeals were dismissed.[11]

Maybe it kills the only piece of morality in you. It could have been my own mother [at the Parkin residence] and I don't think I would have felt anything ... kids ... anybody. I've stopped feeling anything. There's something dead inside me.

Steelman

[edit]Steelman was a troublesome inmate. Prison records indicate repeated conflicts with guards and fellow inmates alike, resulting in numerous spells in solitary confinement, although he and Gretzler remained on affable terms, and never fought each other. He corresponded with numerous individuals, many of whom he deceived into believing his claims of innocence; that he was a Jewish child raised by a Japanese family; that he had only committed his crimes due to despair at having been abandoned throughout his "whole life"; that he was a Vietnam Veteran; that both the Sandberg and Parkin families were murdered solely due to their involvement in narcotics trafficking; and that he was studying to be a church minister, having repented for his crimes. Some of these individuals were duped into sending Steelman gifts or money.[133]

By the early 1980s, Steelman had developed serious health issues, including cirrhosis of the liver, which he was diagnosed with in 1983.[134] By early 1986, Steelman was informed he had less than three years to live. Reportedly, upon being informed of his terminal illness, Steelman stated his impending death was the sole way he would ultimately "beat the state." His health deteriorated rapidly throughout the summer, and he was discovered collapsed in his cell on the morning of August 7, 1986, and rushed to the Maricopa County Hospital, where he died that afternoon. Steelman was later buried at the Temple Beth Israel cemetery in Phoenix.[41][135]

Upon hearing of Steelman's death, the father of Patricia Sandberg, Roderick Mays, stated: "It annoys me that he died of natural causes before he could be executed. He had been condemned to death at every level ... I regret it's such a long, drawn-out process, with so many chances of appeal, that he died of natural causes before he could be executed."[134]

Gretzler

[edit]Following his conviction, Gretzler shunned all contact from his family and the public alike for many years. Although initially viewed as a disciplinary problem, he gradually became a model inmate. Gretzler initially expressed neither remorse for his actions or concern for his own predicament in the years immediately following his arrest, but by the early 1980s, he claimed to have repented for his past deeds. He severed all contact with Steelman, re-instigated contact with his family—apologizing to them for the shame and stigma he had brought upon them—and wrote letters to his victims' relatives in which he expressed remorse for his actions and asked for forgiveness.[34]

In 1992, Gretzler was visited in prison by Jack Earl, a close relative of the Earl family.[136] The two would meet frequently over the course of several years, with Gretzler disclosing to Earl his accounts of his life, his acquaintance with Steelman, and their subsequent actions in October and November 1973. Gretzler expressed remorse to Earl for what he had done and insisted that he felt extreme shame and regret and his belief his impending execution was justified.[137]

By 1998, Gretzler had informed both his family and his attorney, Cary Sandman,[138] of his wish to cease any further efforts to postpone his impending execution. He spent his final days writing dozens of letters to his family, friends, attorney, legal personnel, and relatives of his victims.[139] Neither he or his attorney were present at a June 2, 1998, obligatory reprieve hearing to plead against the scheduled June 3 execution date ordered by Justice Thomas Zlaket.[140]

Execution

[edit]Douglas Gretzler was executed via lethal injection at Florence State Prison at 3:11 p.m. on June 3, 1998.[141] His execution was the first to be conducted during daylight hours in the history of Arizona.[142][n 19] Gretzler's execution was witnessed by 35 people,[56] including four relatives of his victims, one of his younger sisters, two close friends of his, several individuals involved in his apprehension and prosecution, and nine journalists.[137] His last meal—served to him at 7 a.m.—consisted of a platter of six fried eggs, four slices of bacon, two slices of toast, a cup of coffee and two cans of Coca-Cola.[143]

Gretzler's request to wear his glasses at his execution in order that he could see his loved ones as he delivered his last words was granted.[139] Immediately prior to his execution, Gretzler asked those present for forgiveness, and as his final words, said the following:[80]

From the bottom of my soul, I'm so deeply sorry and have been for years for murdering Patricia and Michael Sandberg. Though I am being executed for that crime, I apologize to all 17 victims and their families.

Gretzler then turned towards his sister, telling her in Romanian that he loved her and his two granddaughters before stating in English: "Thank you for life's lessons learned."[139]

As the IV tube was administered to Gretzler's vein, he twice mouthed "I love you" and "Bye" to his sister and friends.[139] At the time of his execution, Gretzler was the longest-serving death row inmate in Arizona's history. His body was later released to his family.[144][80]

Media

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Earl, Jack (2013). Where Sadness Breathes: The True Story of Willie Steelman and Douglas Gretzler and the 17 People they Murdered in the Autumn of 1973. Oregon: Jack Earl Publishing. ASIN B07MX4VW4K.

- Ramsland, Katherine M. (2005). Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-313-36054-1.

Television

[edit]- The Greatest Murder Story Never Told. Commissioned by First Watershed Pictures and directed by Mark Stanoch, this 67-minute documentary contains recorded interviews with Gretzler as he discusses his crimes and was initially broadcast on November 26, 2000. Author Richard Earl is among those interviewed for this documentary.[145]

See also

[edit]Cited works and further reading

[edit]- Douglas, John E.; Olshaker, Mark (1996). Journey Into Darkness. United Kingdom: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-749-32394-3.

- Dunning, John (1992). Mindless Murders. Great Britain: Mulberry Editions. ISBN 1-873-12333-7.

- Earl, Jack (2013). Where Sadness Breathes: The True Story of Willie Steelman and Douglas Gretzler and the 17 People they Murdered in the Autumn of 1973. Oregon: Jack Earl Publishing. ASIN B07MX4VW4K.

- Fox, James Allan (2015). Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder. London: Sage Publishing. ISBN 978-1-483-35072-1.

- Fridel, Emma E.; Fox, James; Levin, Jack (2018). Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder. London: Sage Publishing. ISBN 978-1-506-34911-4.

- Lester, David (2004). Mass Murder: The Scourge of the 21st Century. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc. ISBN 1-590-33929-0.

- Leyton, Elliot (2011) [1986]. Hunting Humans: The Rise of The Modern Multiple Murderer. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-140-11687-8.

- Newton, Michael (2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 0816069875.

- O'Shea, Kathleen A. (1999). Women and the Death Penalty in the United States, 1900-1998. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-95952-4.

- Palmer, Louis J. (2008). Encyclopedia of Capital Punishment in the United States. 2d Edition. North Carolina: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-786-45183-8.

- Ramsland, Katherine M. (2005). Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-36054-1.

- Safarik, Mark; Ramsland, Katherine (2019). Spree Killers: Practical Classifications for Law Enforcement and Criminology. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-367-37000-8.

- Shanafelt, Robert; Pino, Nathan W. (2015). Rethinking Serial Murder, Spree Killing, and Atrocities. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-83298-5.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Although generally placid by nature, the lack of approval Gretzler received from his father as a child and adolescent instilled a lifelong resentment of authority and duty within him.[12]

- ^ This would prove to be the first of numerous periods of incarceration Steelman would receive throughout his life.

- ^ Renslow had first met Mestites—a masseuse and occasional prostitute—in 1972, one year prior to Mestites' July 1973 relocation to Phoenix, where she adopted the name Yahfah Hacohen. She did not disclose her love for Mestites to Steelman or Gretzler; remaining closeted about her sexuality.[25]