William Stanley (inventor)

William Stanley | |

|---|---|

Stanley, c. 1880 | |

| Born | William Ford Robinson Stanley 2 February 1829 Islington, Middlesex, United Kingdom |

| Died | 14 August 1909 (aged 80) South Norwood, Surrey, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse | Eliza Ann Savory |

| Engineering career | |

| Employer(s) | William Ford Stanley and Co. Ltd. |

William Ford Robinson Stanley (2 February 1829 – 14 August 1909) was a British inventor with 78 patents filed in both the United Kingdom and the United States of America. He was an engineer who designed and made precision drawing and mathematical instruments, as well as surveying instruments and telescopes, manufactured by his company "William Ford Stanley and Co. Ltd."

Stanley was a skilled architect who designed and founded the UK's first Trades school, Stanley Technical Trades School (now Harris Academy South Norwood), as well as designing the Stanley Halls in South Norwood. Stanley designed and built his two homes. He was a noted philanthropist, who gave over £80,000 to education projects during the last 15 years of his life. When he died, most of his estate, valued at £59,000, was bequeathed to trade schools and students in south London, and one of his homes was used as a children's home after his death, in accordance with his will.

Stanley was a member of several professional bodies and societies (including the Royal Society of Arts, the Royal Meteorological Society (elected 17 May 1876), the Royal Astronomical Society (elected 9 February 1894) and the British Astronomical Association (elected 31 October 1900)).[1][2] Besides these activities, he was a painter, musician and photographer, as well as an author of a variety of publications, including plays, books for children, and political treatises.

Personal life

[edit]Early life

[edit]William Stanley was born on Monday 2 February 1829 in Islington, London, one of nine children of John Stanley (a mechanic and builder) and his wife, Selina Hickman, and a direct descendant of Thomas Stanley, the 17th-century author of History of Philosophy.[3][4] He was baptised on Wednesday 4 March 1829 at St Mary's Church, Islington.[4] At the age of 10 Stanley started going regularly to a day school run by a Mr Peil until he was 12. From the age of 12 until he was 14, his maternal uncle William Ford Hickman paid for his education at a different school.[5] Despite having limited formal learning, Stanley taught himself mathematics, mechanics, astronomy, music, French, geology, chemistry, architecture and theology.[6] He attended lessons in technical drawing at the London Mechanics’ Institution (now called Birkbeck College), where he enrolled in 1843, attending engineering and phrenology lessons.[5]

While living in Buntingford between 1849 and 1854, Stanley founded a literary society with a local chemist. They charged a subscription of five shillings a year. This was spent on books to form a library which grew to 300 volumes. They had many guest speakers, and on one occasion Lord Lytton, the author of The Last Days of Pompeii, came to address the Society on Pompeii.[7] Being "intensely interested" in architecture, he submitted a design for a competition in The Builder magazine, but did not win.[7]

Starting work

[edit]In 1843, Stanley's father insisted that he leave school, at the age of 14, and help him in his trade.[7] Stanley worked in his father's unsuccessful building business, becoming adept at working with metal and wood, later to obtain employment as a plumber/drainage contractor and joiner in London.[4] He joined his father in 1849 at an engineering works at Whitechapel, working as a Pattern Maker's Improver[7] where he invented the steel wheel spider-spokes.[7] His father discouraged him from seeking a patent for this invention.[4] For the following five years, he was in partnership with his maternal uncle (a Mr Warren), a builder, at Buntingford.[3]

Family life

[edit]In 1854, Stanley fell in love with a girl in Buntingford, Bessie Sutton, but her family refused to let them marry.[8] On 2 February 1857 (Stanley's 28th birthday), he married Eliza Ann Savory.[4] They lived "above the shop", as they could afford only to rent four rooms in the same street as his shop.[8] Five years later, the couple moved to Kentish Town, later moving to South Norwood in the mid-1860s.[8][9] The couple adopted Stanley's niece Eliza Ann and another child, Maud Martin, whose father and brother drowned at sea.[4]

Entrepreneur

[edit]

Starting own company

[edit]Stanley acted upon a remark made by his father in 1854 about the high cost and poor quality of English drawing instruments compared to those imported from France and Switzerland, and started a business making mathematical and drawing instruments.[4] At first he rented a shop and parlour at 3 Great Turnstile, Holborn, and began the business with £100 capital. He invented a new T-square which improved the standard one and became universally used. A cousin, Henry Robinson, joined him with a capital of £150, but died in 1859.[3][4][8] Stanley stopped using the name Robinson and changed his signature as a consequence of being robbed of his cheque book during the early days of his business.[4]

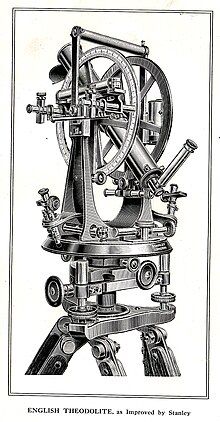

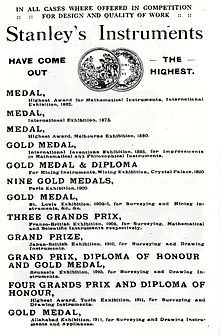

Stanley produced a 'Panoptic Stereoscope' in 1855, which was financially successful.[4] Stereoscopes had sold for five shillings each – Stanley discovered a simpler method to make them, which enable him to sell them for one shilling.[8] He was able to take an additional shops at 3–4 Great Turnstile and 286 High Holborn, as well as a skilled assistant.[3] He did not patent the Panoptic, so it was soon copied around the world, but he had sold enough to provide the capital required to manufacture scientific instruments.[8] In 1861 he invented a straight line dividing machine for which he won first prize in the 1862 International Exhibition in London.[3][10] Stanley brought out the first catalogue of his products in 1864.[8] By the fifth edition, Stanley was able to list important customers such as several government departments, the Army, the Royal Navy, railways at home and abroad, and London University.[11] From 1865, he worked on improving the elegance and stability of surveying instruments, especially the theodolite, whose construction he simplified.[3][4] It had a rotating telescope for measuring horizontal and vertical angles and able to take sights on prominent objects at a distance. The component parts were reduced to fewer than half of the 226 used in the previous version, making it lighter, cheaper and more accurate.[12]

Designing/building homes and factory

[edit]Stanley designed and set up a factory in 1875 or 1876 (called The Stanley Works, it was listed in the 1876 Croydon Directories as Stanley Mathematical Instruments) in Belgrave Road near Norwood Junction railway station, which produced a variety of instruments for civil, military, and mining engineers, prospectors and explorers, architects, meteorologists and artists, including various Technical drawing tools.[6][9][13][14] The firm moved out of the factory in the 1920s, with the factory being occupied by a joinery firm until, following a fire, it was converted into residential use in 2000.[14]

In South Norwood, Stanley designed and built his two homes Stanleybury, at 74–76 Albert Road and Cumberlow Lodge in Chalfont Road.[3] Cumberlow Lodge was originally Pascall's large brickfield dating from the early part of the 19th century, and subsequently a dairy farm. When it closed the 6 acres (0.024 km2) of land was purchased in 1878 by Stanley.[14] It was written into his will that the building should be used only as a children's home, and it was used for this purpose for over a century.[6][9] In 1963, ownership was transferred to the London Borough of Lambeth and child murderer Mary Bell was housed there for a short time, until the local residents protested and she was removed to Wales.[15] It was knocked down in 2006 before it could become a listed building.[16][17]

The company expands

[edit]

By 1881, Stanley was employing 80 people and producing 3,000 technical items, as detailed in his catalogue.[9] A few years later, in 1885, Stanley was given a gold medal at the International Inventors Exhibition at Wembley.[9] The rapid growth of his business led to the opening of branches at Lincoln's Inn, at London Bridge and at South Norwood.[4] His 1890 catalogue shows that the company were selling Magic Lanterns, with a variety of slides including such subjects as the siege of Paris (1870–1871), the travels of Dr Livingstone and Dante's Inferno, as well as improving stories for children such as Mother's Last Words and The Drunkard's Children, while in the catalogue for 1891, Stanley refers to the company having 17 branches, with over 130 workmen.[18]

Flotation of company

[edit]On 20 April 1900 his company was floated on the stock market, becoming a limited company under the name of William Ford Stanley and Co Ltd. Around 25,000 shares in his company sold at £5 each, giving an authorised capital of £120,000.[3][9] Stanley retired from the company (although still acting as Chairman of the Board and Managing Director), leaving Henry Thomas Tallack (a business partner) and his brother Joseph to run the day-to-day operations.[11] By 1903 (when the company reached its golden jubilee), it claimed to be the "largest business of its kind in the world".[18]

Membership of professional bodies and societies

[edit]Stanley was a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (1862), the Geological Society of London (elected 9 January 1884), the Royal Astronomical Society (elected 9 February 1894), and a life fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society (1876) He was also a member of the Physical Society of London (elected 25 February 1882) and the British Astronomical Association (1900), as well as a member of the Croydon School Board from 1873.[3][4][19]

Stanley read many papers to the various societies, including Clocks (1876, to the Royal Meteorological Society), The Mechanical Conditions of Storms, Hurricanes and Cyclones (1882, to the Royal Meteorological Society), Forms of Movements in Fluids (1882, to the Physical Society of London), Integrating Anemometer (1883, to the Royal Meteorological Society), Earth Subsidence and Elevation (1883, to the Physical Society of London), Certain effects which may have been produced from the eruptions of Krakatoa and Mount St. Augustin (1884, to the Royal Meteorological Society), Improvement in Radiation Thermometers (1885, to the Royal Meteorological Society), Three years' work with the chrono-barometer and chrono-thermometer (1886, to the Royal Meteorological Society), The Phonometer (1891, to the Royal Meteorological Society) and Perception of Colour (1893, to the Physical Society of London).[13][19]

Final years and death

[edit]Travels and art

[edit]Following his election as a Fellow of the Geologists' Association, he went on an expedition to the Ardennes and the River Meuse.[13] He visited Egypt and Palestine in 1889, and Switzerland in 1893.[4][20] In 1900 Stanley travelled to Navalmorel in Spain to observe the total solar eclipse of 28 May.[21]

He engaged in different forms of art. In 1891, three of his oil paintings were exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery and in May 1904, a carved inlaid tray Stanley had made was shown at the Stanley Art Exhibition Club.[3][13] He also enjoyed composing partsongs, painting, playing music and photography.[4][9]

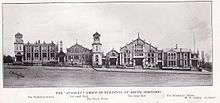

Building the UK's first Technical Trades School and Stanley Halls

[edit]

Stanley decided in 1901 to build and set up Stanley Technical Trades School, the first of its kind in the country. The school was designed to educate boys between the ages of 12 and 15 in general studies, as well as trade. It was made to Stanley's own design and included an astronomy tower, and opened in 1907. When it was presented to the public in 1907, it had an endowment valued at £50,000.[3] It was later renamed as Stanley Technical School (now Harris Academy South Norwood).[22] The William F. Stanley Trust (originally The Stanley Foundation) was set up as a charitable Trust to assist with the management of the Stanley Technical Trades School. On 23 November 2006, Lady Harris (wife of Philip Harris, Baron Harris of Peckham, founder of the Harris Federation) and David Cameron (at the time, the leader of the Conservative Party and the Leader of the Opposition) placed a time capsule to recognise the contribution of Stanley to South Norwood. The capsule included a letter from Cameron, a copy of the speech given by William Stanley, on the opening of the Stanley Technical Trades School on 26 March 1907, two reference books (William Stanley the Man; William Stanley’s School), as well as artefacts from both Stanley Technical High School for Boys and the Harris Federation of schools.[23]

Stanley Halls (in South Norwood) were opened on 2 February 1903 by Charles Ritchie, 1st Baron Ritchie of Dundee at a cost of £13,000 (as Stanley Public Hall) to provide the local community with a public space for plays, concerts and lectures.[11] It was the first building in Croydon to have electricity.[24] In 1904 a clock tower and a hall were added.[9][25][26] In 1993, a blue plaque was installed on a wall of Stanley Halls by English Heritage. The plaque reads W.F.R. STANLEY (1829–1909) Inventor, Manufacturer and Philanthropist, founded and designed these halls and technical school.[27][28] It is a Grade II listed building.[29]

Legal work and Freedom of the City

[edit]Stanley became a magistrate (Justice of the peace), and sat on the Croydon Bench on Mondays and Saturdays.[13] He had a reputation for helping the poor, and when he retired from the Bench, one of his colleagues commented that there would be "no more £10 notes put in the poor-box".[13] In July 1907 he was given the freedom of the borough of Croydon, an honour which is bestowed on people that the council (at that point, the Corporation of Croydon) feel have made a significant contribution to the borough.[9] Stanley was the fourth person to be accorded this honour.[30]

Funeral

[edit]

Stanley died on 14 August 1909 of a heart attack, aged 80.[31] His funeral was held on 19 August, and "local flags were flown at half mast, shops closed and local people drew their curtains as a mark of respect as a cortege of 15 carriages drew past."[9] The first 14 carriages were filled with family and dignitaries, whilst the 15th carried the domestic staff from Cumberlow.[31] The cortege went to Elmers End Cemetery in Beckenham at walking pace and was met at the gates of the Cemetery by scholars from the School and members of staff from the firm.[31] He was buried in the part of the Cemetery reserved for those who attended St. John's Church, Upper Norwood.[31] His tomb has a fine portrait carved in stone.[31] When his widow died in 1913, she was placed in the tomb beside Stanley.[31] There were obituaries in several national and local newspapers and journals, including The Times, The Norwood Herald, The Norwood News, The Engineer, The Electrical Review, The Electrician, Engineering and The Journal of the Geological Society of London.[31] On Saturday 22 August 2009, a memorial service in his honour was held at his grave in Beckenham Cemetery to mark the centenary of his death.[22]

Benefactions

[edit]During the last 15 years of his life, Stanley gave over £80,000 to education projects. Most of his estate was bequeathed to trade schools and students in south London.[6]

Stanley's will was signed on 20 March 1908, and was probated on 26 October 1909.[4][32] When he died, his wealth was £58,905 18s. 4d.[4] The will provided for Stanley's wife, and each nephew, niece, great-nephew and great-niece were mentioned by name, and left money and shares. His brother's wife and his adopted daughter also received shares. Every servant received £5, as did each teacher in the school. Every factory employee received £2. Several individuals received monthly incomes of £1 or £2 a month.[32] Croydon General Hospital, the Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society, The British Home and Hospital for Incurables, Croydon Police Court Relief Fund and Croydon Society for the Protection of Women and Children all received shares, as did the Croydon Corporation, although these were to be used for the purchase of books annually to be used as prizes for students in Croydon.[32]

Legacy

[edit]Company

[edit]The W.F. Stanley and Co. company continued to expand after Stanley's death, moving to a factory in New Eltham (The Stanley Scientific Instrument Works) in 1916.[32] During World War I, the factory was requisitioned by the government.[32] Between the wars, it continued to expand its position in the market place for quality surveying instruments, although it was requisitioned by the British Government during World War II.[32] After the war, the company continued to expand, participating in many large projects – for example, RMS Queen Mary and Royal Navy ships used the company's compasses and other navigational instruments.[32] The company went into liquidation in July 1999 – the main factors were not investing the proceeds of the sale of the factory land to buying new machinery, the high value of the pound affecting export orders, and the loss of Ministry of Defence orders following the end of the Cold War.[32]

Clock tower

[edit]

A cast-iron clock tower was erected in South Norwood at the junction of Station Road and the High Street in 1907 to mark the golden wedding anniversary of William and Eliza Stanley, as a measure of the esteem in which they were held in the locality.[6]

Wetherspoon's pub

[edit]

On 18 December 1998, the Wetherspoon's pub chain opened The William Stanley on the High Street in South Norwood.[33] It is a 19th-century style of building, with a portrait of Stanley inside, as well as pictures of other Norwood notables (Lillie Langtry, H. Tinsley (another scientific instrument maker), Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Brock).[32] This pub was closed in 2016 and has re-opened as the Shelverdine Goathouse. The William Stanley pub sign and memorabilia from the pub were donated to Stanley Halls where they are on show.[citation needed]

Selected inventions and patents

[edit]78 patents are attributed to Stanley (sometimes the number is quoted as 79, as in 1885 a proposed patent application was never followed through)[18] Many of the patents Stanley applied for were improvements on techniques or of other patents.[34]

- 1849: Wire bicycle ('spider-wheel') spokes[3]

- 1861: Application of aluminium to the manufacture of mathematical instruments (UK patent 1861 number 3,092)[3][19]

- 1863: Drawing instrument for drawing circles or arcs from 2 to 200 feet (0.61 to 60.96 m) radius (UK patent 1863 number 226)[18][19]

- 1866: Mathematical Drawing Instruments (UK patent 1866 number 644)[19]

- 1867: Meteorological Instrument – Meteorometer – to record simultaneously wind direction and pressure, temperature, humidity and rainfall (UK Patent 1867 number 3,335)[18][19]

- 1868: Machines for exciting frictional electricity (UK Patent 1868 number 3,878)[19]

- 1870: Drawing Boards, Straight Edges, etc. (UK Patent 1870 number 2,264)[19]

- 1872: Electrical Apparatus – an improved method of constructing portable galvanic batteries (UK Patent 1872 number 2,213)[19]

- 1874: Circular Saw Bench (UK Patent 1874 number 411)[19]

- 1874: Points for Mathematical Drawing Instruments – an improvement in compass points (UK Patent 1874 number 412)[19]

- 1875: Pendulums for equalising pressure and temperature and calculating time (UK Patent 1875 number 4,130)[19]

- 1880: Apparatus for measuring distances (UK Patent 1880 number 2,142)[19]

- 1880: Photographic Cameras – improvements in the lens-mounting, the dark slide and the body of the camera (UK Patent 1880 number 3,358)[19]

- 1882: Photographic Cameras – a focal scale affixed to the camera (UK Patent 1882 number 3,268)[19]

- 1883: Integrating Anemometer (UK Patent 1883 number 672)[3][19]

- 1885: Buffer for the prevention of collisions on land and water (UK patent 12,953 granted 28 December 1885; US patent 345,552 granted 13 July 1886)[19][35]

- 1885: Actinometer[19][34]

- 1885: Barometer and snow gauge[34]

- 1885: Tooth Injectors (UK Patent 1885 number 15,115)[19]

- 1886: Improvements in Chandeliers and Pendants – to allow the workings used in raising and lowering lamps to be concealed (UK Patent 1886 number 2,701)[19][34]

- 1886: Improvements in the Focussing Arrangements of Cameras (UK Patent 1886 number 2,811)[19]

- 1886: Improvement in Knives – an improved carving knife (UK Patent 1886 number 3,357)[19]

- 1886: Press for rending steaks tender (UK Patent 1886 number 3,991)[19]

- 1886: Machine for automatically measuring people's height (one of the first 'penny in the slot' machines) (caricatured in Moonshine and Scraps magazine) (UK patent 4,726 granted 5 April 1886; US patent 404,317 granted 28 May 1889)[19][36][37][38]

- 1886: Portable Saw (UK Patent 1886 number 10,589)[19][34]

- 1886: William's Pantograph[39]

- 1887: Heat Conductors for baking and boiling (UK Patent 1887 number 7,244)[19]

- 1887: Apparatus connected with Spirometers for determining lung capacity. (caricatured by H Furniss in the Yorkshire Evening Post) (UK Patent 1887 number 13,013)[19][34][40]

- 1888: Pen Extractor (UK patent 17,078 granted 23 November 1888; US patent 479,959 granted 2 August 1892)[19][41]

- 1889: Improvements in Mining Stadiometers, Theodolites and Tacheometers (UK Patent 1889 number 12,590)[19][34]

- 1889: Improvements in Lemon Squeezers (UK Patent 1889 number 18,735)[19]

- 1890: Improvements in Apparatus for Measuring Distances – a device by which distances could be measured by the time sound took to travel, and was applied to rifles and artillery (UK Patent 1890 number 3,683)[19]

- 1892: Improvements in Tribrach Arrangements for Instruments of Precision (UK Patent 1892 number 14,934)[19][34]

- 1894: Improvements in Planimeters (UK Patent 1894 number 13,567)[19][34]

- 1895: Improvements in Surveyor's Levels (UK Patent 1895 number 6,229)[19]

- 1898: Improvements in Mining Surveying Instruments – a device for taking sights vertically downwards, such as that down a shaft (UK Patent 1898 number 9,134)[19]

- 1898: Improvements in Drawing Boards and Tee Squares (UK Patent 1898 number 22,710)[19]

- 1899: Improvements in Surveying Instruments – a device by which the angle through which the instrument had been turned recorded itself on a dial (UK Patent 1899 number 7,864)[19]

- 1899: Machine for cutting Brazilian Quartz lenses for spectacles[34]

- 1900: Improvements in Dark Slides for Cameras (UK Patent 1900 number 7,664)[19]

- 1900: Improvements in Rotary engines (UK Patent 1900 number 17,838; US Patent 717,174 granted 19 August 1902)[19][42]

- 1901: Improvements in Surveyor's Levels – casting the tube and vertical axis of the level in one piece (UK Patent 1901 number 10,447)[19]

- 1902: Improvement in Self-holding Double Eyeglasses (UK Patent 1902 number 19,909)[19]

- 1902: Improvement for Fixing Stone Skirtings to the walls of Buildings – this was used in parts of the Technical School Buildings (UK Patent 1902 number 20,222)[19]

- 1903: Improvements in Gauges and Rods for Standard Measures – for taking exact inside and outside measures by the same gauge (UK Patent 1903 number 26,754)[19]

- 1905: Improvements in and relating to Perspective Drawing Tables *UK Patent 1905 number 6,167)[19]

- 1908: Improved Appliance for Mending Surveyors' Band Chains (UK patent 1908 number 1,931, granted 29 January 1908) (this was Stanley's last patent)[11][19]

Selected books

[edit]

- 1866 A descriptive treatise on mathematical drawing instruments : their construction, uses, qualities, selection, preservation, and suggestions for improvements, with hints upon drawing and colouring (which became the standard authority, in its seventh edition by 1900)[3][43]

- 1867 Proposition for a New Reform Bill to Fairly Represent the Interests of the People (Simpkin, Marshall & Co., London) (Proposing a simple form of Proportional representation)[3]

- 1869 Electric disc and experiments, by a positive conductor (W.F. Stanley, Patentee, London)

- 1872 Photography Made Easy: A Manual for beginners (Gregory, printers)[3]

- 1875 Stanley's Pretty Figure Book Arithmetic (reprinted 1881)[3]

- 1881 Experimental Researches into the Properties and Motions of Fluids: With theoretical deductions therefrom (E. & F.N. Spon) (this work was commended by Darwin and Tyndall. A supplemental work on sound motions in fluids was unfinished)[3]

- 1890 (with Tallack, H.T.) Surveying and levelling instruments theoretically and practically described: for construction, qualities, selection, preservation, adjustments, and uses; with other apparatus and appliances used by civil engineers and surveyors in the field (E. & F.N. Spon, London) – in its fourth edition by 1914[3]

- 1895 Notes on the Nebular Theory in Relation to Stellar, Solar, Planetary, Cometary, and Geological Phenomena (William Ford Stanley, London)[3]

- 1896 Joe Smith and his Waxworks (Fictional portrayal of the life of travelling fair people, but with an underlying message about the treatment of children. Written by "Bill Smith, with the help of Mrs. Smith and Mr. Saunders (W.F.S)")[3][44]

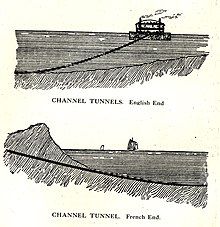

- 1903 The Case of The. Fox: a Political Utopia (Stanley's prediction of life in 1950, including predictions of the Channel Tunnel, a unified Europe, a simplified currency, amongst others)[3][45]

- 1905 "Turn to the Right." Or, a Plea for a Simple Life. A comedy in four acts (Coventry & Son) – A play performed in the Stanley Halls in May 1905[44]

Selected magazine articles

[edit]- 1877 "Barometrical and Thermometrical Clocks for Registering Mean Atmospheric Pressure and Temperature" (Journal of the Meteorological Society, Volume 3)[44]

- 1882 "Mechanical conditions of storms, hurricanes, and cyclones" (Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, London)[46]

- 1885 "A suggestion for the improvement of radiation thermometers" (Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, London), Volume 11, Issue 54, pp. 124–127[44]

- 1886 "On three years' work with the chrono-barometer and chrono-thermometer, 1882–84" (Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, London), Volume 12, Issue 58, pp. 115–120[44]

- 1886 "A Simple Snow-gauge" (Journal of the Meteorological Society, London), Volume 12[44]

- 1887 "The Structure of the Human Race" (Nature, Alexander Macmillan, Cambridge), Volume 36[44]

- 1891 "Note on a New Spirometer" (Journal of the Anthropological Institute, London), Volume 20[44]

References

[edit]- ^ "1894MNRAS..54..178. Page 178". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 54: 178. 1894. Bibcode:1894MNRAS..54..178. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "1900JBAA...11...47. Page 47". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 11: 47. 1900. Bibcode:1900JBAA...11...47. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Owen, W.B. (1912). Sir Sidney Lee (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography – William Ford Robinson Stanley. Second Supplement. Vol. III (NEIL-YOUNG). London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 393–394.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q McConnell, Anita (2004). "Stanley, William Ford Robinson (1829–1909)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36250. Retrieved 9 September 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Akpan, Eloïse (2000). The Story of William Stanley - A Self-made Man. London: Eloïse Akpan. ISBN 0-9538577-0-0. Chapter II: Childhood and Education

- ^ a b c d e Whalley, Kirsty (10 April 2009). "Croydon legend being erased from history books". The Croydon Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Akpan Chapter III: Employment

- ^ a b c d e f g Akpan Chapter IV: Setting up in Business

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bruccoleri, Jane (12 July 2006). "Longlasting legacy". The Croydon Guardian. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ William Newton, ed. (1865). "New Patents Sealed". The London Journal of Arts and Sciences (And Repertory of Patent Inventions). 21. London: Newton and Son (at the Office for Patents): 876. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d Akpan Chapter VIII: Retirement and Launching of Limited Company

- ^ Akpan Chapter I: Who was William Stanley?

- ^ a b c d e f Akpan Chapter VI: Move to Norwood

- ^ a b c "South Norwood Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan South Norwood Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan". Croydon Council. 25 June 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Akpan Chapter VII: Cumberlow

- ^ Lidbetter, Ross (19 November 2008). "Builders fined for demolishing part of listed Selhurst building". The Croydon Post. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Binney, Marcus (8 February 2007). "Bulldozers outpace the Heritage bureaucrats". The Times. UK. Retrieved 9 September 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Akpan Chapter V: Catalogues

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Inwards, Richard (1911). William Ford Stanley: His Life and Work. London: Crosby Lockwood & Co. Appendix II: Dates and Events

- ^ Akpan Appendix 2: Travel

- ^ British Astronomical Association; Maunder, E. Walter (Edward Walter) (1901). The total solar eclipse, 1900; report of the expeditions organized by the British astronomical association to observe the total solar eclipse of 1900, May 28. University of California Libraries. London, "Knowledge" office.

- ^ a b "School founder's memorial service". The Croydon Post. 26 August 2009. p. 11.

- ^ "The New Harris Academy, South Norwood" (PDF). Education Department e-bulletin. Croydon Council. December 2006. p. 5. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Lidbetter, Ross (20 June 2008). "Can you help save Stanley Halls?". Croydon Advertiser. Northcliffe Media Group. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "William Stanley, the man who left his mark on South Norwood". The Croydon Post. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "On with the show – decaying theatre 'jewel' to get facelift". The Croydon Advertiser. 31 October 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "STANLEY, W.F.R. (1829–1909)". English Heritage. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "William Ford Robinson Stanley (includes photograph of plaque)". Plaques of London. 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Whalley, Kirsty (1 September 2010). "Stanley abandoned". Croydon Guardian. Newsquest Media Group. p. 14. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Previous Freemen". Croydon Online. Croydon, UK: Croydon Council. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Akpan Chapter IX: Death

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Akpan Chapter X: Stanley's Heritage

- ^ "South Norwood Pubs – The William Stanley – a J D Wetherspoon pub". Wetherspoons. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Akpan Appendix 1: Some Inventions

- ^ Stanley, William Ford (13 July 1886). "Patent:William Ford Stanley: Buffer for the prevention of collisions on land and water". United States Patent Office. Retrieved 14 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Stanley, William Ford (13 July 1886). "Patent:William Ford Stanley: Machine for Measuring the Height of Human Bodies Automatically". United States Patent Office. Retrieved 14 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Caricature of Stanley's height measuring machine". Moonshine. 6 October 1888.

- ^ "Caricature of Stanley's height measuring machine". Scraps. 8 December 1888.

- ^ "W F Stanley pantograph". Museum of Croydon. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Furniss, H (6 September 1890). "Caricature of Stanley's Spirometer". Yorkshire Evening Post.

- ^ Stanley, William Ford (2 August 1892). "Patent: William Ford Stanley: Pen-Extractor". United States Patent Office. Retrieved 14 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Stanley, William Ford (18 August 1902). "Patent:William Ford Stanley: Rotary Engine". United States Patent Office. Retrieved 14 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Rosin, Paul L. (2004). On the Construction of Ovals (citations). Proceedings of Int. Soc. Arts, Mathematics, and Architecture. pp. 118–122. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.4.723.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Akpan Appendix 3: Publications

- ^ Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Bleiler, Richard (ed.). Science-fiction, the early years: a full description of more than 3,000 science-fiction stories from earliest times to the appearance of the genre magazines in 1930 : with author, title, and motif indexes (Illustrated ed.). Ohio: Kent State University Press. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-87338-416-2. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

william ford stanley.

- ^ Stanley, William Ford (1882). "Mechanical conditions of storms, hurricanes, and cyclones". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 8 (44). London: Royal Meteorological Society: 244–251. Bibcode:1882QJRMS...8..244S. doi:10.1002/qj.4970084405. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Allen, Cecil J. (1953). A Century of Scientific Instrument Making, 1853–1953 – A history of W. F. Stanley and Co. London: W.F. Stanley and Co.

- Anderson, R.G.W.; Burnett, J.; Gee, B. (1990). Handlist of Scientific Instrument-Makers' Trade Catalogues, 1600–1914. National Museum of Scotland. ISBN 978-0-948636-46-2.