Willemstad

Willemstad | |

|---|---|

View of Central Willemstad Basilica of St Anne Willemstad Town Hall Temple Emanu-El Penha Building | |

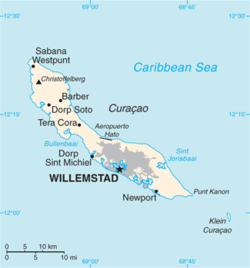

Willemstad on Curaçao | |

| Coordinates: 12°7′N 68°56′W / 12.117°N 68.933°W | |

| State | Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Country | Curaçao |

| Established | 1634 |

| Quarters | Punda, Otrobanda, Scharloo, Pietermaai Smal |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

• Total | 136,660 |

| Official name | Historic Area of Willemstad, Inner City and Harbour, Curaçao |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv, v |

| Reference | 819 |

| Inscription | 1997 (21st Session) |

| Area | 86 ha |

| Buffer zone | 87 ha |

Willemstad (/ˈwɪləmstɑːt, ˈvɪl-/ WIL-əm-staht, VIL-, Dutch: [ˈʋɪləmstɑt] , Papiamento: [wiləmˈstad]; lit. 'William Town') is the capital and largest city of Curaçao, an island in the southern Caribbean Sea that is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It was the capital of the Netherlands Antilles prior to that entity's dissolution in 2010. The city counts to have around 90% of Curaçao’s population, with 136,660 inhabitants as of 2011.[2] The historic centre of the city consists of four quarters: the Punda and Otrobanda, which are separated by the Sint Anna Bay, an inlet that leads into the large natural harbour called the Schottegat, as well as the Scharloo and Pietermaai Smal quarters, which are across from each other on the smaller Waaigat harbour. Willemstad is home to the Curaçao synagogue, the oldest surviving synagogue in the Americas. The city centre, with its unique architecture and harbour entry, has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

History

[edit]Punda was established in 1634, when the Dutch West India Company captured the island from Spain. The original name of Punda was de punt in Dutch. The city was constructed as a walled city.[3] It soon developed into one of the major centres of the Atlantic slave trade which triggered a rapid population growth.[4] In 1674, the Curaçao synagogue was built by Sephardic Portuguese Jews from Amsterdam and Recife, Brazil who had settled in the city as traders.[5] In the late 17th century, there were over 200 houses within the city walls.[3]

In 1675, it was decided to construct the town of Pietermaai outside of the enclosed city. It was to be separated from the city by an area of about 500 metres in which construction was not allowed so as not to obstruct the cannons in Fort Amsterdam.[6] In 1707, the suburb of Otrobanda was founded. Otrobanda would become the cultural centre of Willemstad. Its name originated from the Papiamentu otro banda, which means "the opposite side".[7] The suburb of Scharloo followed, however Willemstad continued to experience growth.[4] By 1818, the population of Willemstad had grown to 9,536 people.[8] On 13 May 1861, a decision was made to demolish the city walls, and build residential houses in the gap separating Willemstad from Pietermaai.[4]

Around 1925, the booming oil and phosphate industry further stimulated growth, and resulted in the creation of new neighbourhoods.[9] Between 1945 and 1955, Julianadorp and Emmastad were created by Royal Dutch Shell to house the new workers.[10] In 1985, the oil refinery which employed 12,000 people was closed down by Shell. The Government of Curaçao decided to buy the refinery for ƒ 1.00 and take responsibility for all future pollution claims. In 1986, it was leased to the Venezuelan PDVSA, and reopened on a limited scale.[11] In 2017, the PDVSA was hit by punitive sanctions of the United States Government,[12] and attempts have been made to seize the refinery.[11]

On 30 May 1969, the Curaçao uprising, a strike at a subcontractor of the oil refinery, turned into a riot. The riot resulted in two deaths, 300 arrests and a part of the historic centre being burnt down. The Netherlands Marine Corps was sent to Willemstad and the entire city centre was closed down.[13] In 1997, the centre of Willemstad and its former suburbs were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[14] In the 21st century, a largescale program of renovation started.[15][16]

Economy

[edit]Aviation

[edit]Jetair Caribbean, the national airline of Curaçao, has its corporate head office in Maduro Plaza.[17]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism is a major industry and the city has several casinos. The city centre of Willemstad has an array of colonial architecture that is influenced by Dutch styles. Archaeological research has also been developed there.[18] The city is also home to several beaches like Baya Beach.[19]

Industry

[edit]Owing to its location near the Venezuelan oilfields, its political stability and its natural deep water harbour, Willemstad became the site of an important seaport and refinery. Willemstad's harbour is one of the largest oil handling ports in the Caribbean. The refinery, at one point the largest in the world, was originally built and owned by Royal Dutch Shell in 1915.[20]

The four companies comprising the Royal Dutch Shell[21] refining operation; the actual refinery, oil bunkering, the tugboat company (KTK) and the local distribution of refined products (CurOli/Gas) were each sold to the government of Curaçao in 1985[22] for the symbolic sum of one guilder per company, or a total of 1 guilder[23] and is now leased to PDVSA, the state owned Venezuelan oil company. Schlumberger, the world's largest oil field services company is incorporated in Willemstad.[24]

Financial services

[edit]Numerous financial institutions are incorporated in Willemstad due to Curaçao's favourable tax policies.

Education

[edit]The University of Curaçao is the national university of Curaçao and located in Willemstad.[25] The Avalon University School of Medicine is located in Willemstad. The Caribbean Medical University[26] is also located in Willemstad, close to the city centre.

Sports

[edit]

Major League Baseball players Jair Jurrjens, Wladimir Balentien, Jurickson Profar, Andruw Jones, Ozzie Albies, Kenley Jansen, Jonathan Schoop and Andrelton Simmons are from Willemstad.

Noted tennis doubles player Jean-Julien Rojer was born in Willemstad.

Enith Brigitha, a bronze medalist swimmer who represented the Netherlands in the Summer Olympics was born in Willemsted. She was also the first black athlete to win a swimming medal at the Olympics.

In 1985, Willemstad hosted the Curaçao Grand Prix for Formula 3000. The race was won by Danish racing driver John Nielsen. Pabao Little League has appeared in nine Little League World Series, winning in 2004. They were crowned the International Champions in 2005, 2019, 2022, and 2023. In 2008, another Pabao Little League team won the Junior League World Series, after winning the Latin America Region, then defeating the Asia-Pacific Region and Mexico Region champions to become the International champion, and finally defeating the U.S. champion (West Region), Hilo American/National LL (Hilo, Hawaii), 5–2.

Infrastructure

[edit]

Airport

[edit]Willemstad is served by Curaçao International Airport, located 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) north of the city, which is annually used by about two million passengers.

Bridges

[edit]Punda and Otrobanda are connected by Queen Emma Bridge, a long pontoon bridge. Although it is still in use, these days most road traffic now uses the Queen Juliana Bridge built in 1967 (rebuilt 1974) which arches high over the bay further inland. Nearby is also the now non-functioning Queen Wilhelmina drawbridge.

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- Kemy Agustien, footballer[27]

- Ozzie Albies, Major League Baseball player

- Tahith Chong, footballer

- Rebecca Cohen Henriquez, activist[28]

- Guliano Diaz, former professional footballer

- Luigison V. Doran, footballer

- Jan Helenus Ferguson, Colonial governor of the Dutch Gold Coast[29]

- Elson Hooi, footballer[30]

- Jacky Jakoba, baseball player[31][32]

- Andruw Jones, baseball player[33]

- George Maduro, World War II resistance member and recipient of the Military Order of William

- Manuel Piar, general-in-chief of the army during the Venezuelan War of Independence

- Jean-Julien Rojer, tennis player

- Gerrit Schotte, 1st Prime Minister of Curaçao

- Jonathan Schoop, baseball player[34]

- Kenley Jansen, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Luis Brión, admiral during the Venezuelan war of independence

- Jurickson Profar, Major League Baseball player

Gallery

[edit]-

Colorful historic part of Willemstad

-

Buildings in historic area of Willemstad

-

Banco di Caribe

-

Historic Area of Willemstad, Inner City and Harbour was declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997

-

Queen Emma floating bridge in Willemstad

-

Queen Emma Bridge by night

-

Penha Building, built in 1708

-

The Queen Juliana Bridge over St. Anna Bay in Willemstad, Curaçao

References

[edit]- ^ "Curaçao". City Population. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Curaçao". City Population. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Pietermaai Suburb". Curaçao History. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Benjamins & Snelleman 1917, p. 747, .

- ^ "Curacao Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Library. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Michael A. Newton (1990). "Architectuur en monumentenzorg". De Gids (in Dutch). p. 658.

- ^ Benjamins & Snelleman 1917, p. 747: Dutch: Overzijde English: Opposite side

- ^ Benjamins & Snelleman 1917, p. 749.

- ^ Buurtprofiel Steenrijk (2011). "Buurtprofiel Steenrijk" (PDF). Government of Curaçao (in Dutch). p. 9. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Ontwikkeling huisvesting op Curaçao door Shell". National Archive of Curaçao (in Dutch). Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Het rottend hart dat Curaçao splijt: wat moet het eiland met zijn vuile raffinaderij?". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Curacao oil refinery takeover: Good for jobs, bad for climate?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Curaçao Trinta di Mèi". Dutch National Archive (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Historische Wijken". Curacao.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Buurtprofiel Scharloo (2011). "Buurtprofiel Scharloo" (PDF). Government of Curaçao (in Dutch). p. 10. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "The local SOHO on Curaçao:The Pietermaai District". Dolfijn Go. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "General conditions" (Archive) Insel Air. Retrieved on 21 March 2014. "Our Registered Address is Dokweg 19, Maduro Plaza, Willemstad, Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles."

- ^ "Willemstad : a road to a methodical way of conducting archaeological research for Curaçao by Amy Victorina". Manioc.org. 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- ^ "Baya Beach". Cruisebe. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Curaçao Investment Corp page describing the refinery". Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ Shell, Willemstad page.

- ^ "Refinery deal in Curaçao". New York Times. 1985-09-26.

- ^ Op 23 september van dat jaar deed Shell, na maandenlange onderhandelingen met de Antilliaanse en Nederlandse regeringen, de raffinaderij aan de Buscabaai alsmede de tankopslag, het sleepbootbedrijf en de lokale verkoopmaatschappij voor een gulden per bedrijf, dus in totaal vier gulden, 'met alle lusten en lasten' over aan de Nederlandse Antillen en Curaçao. nrc.ln/nieuws

- ^ "Schlumberger N.V. - Company Information".

- ^ "University of Curaçao". Dutch Culture. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Caribbean Medical University, official website.

- ^ "K. Agustien". Soccerway. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Goldish, Josette Capriles (17 October 2002). "The Girls They Left Behind Curaçao's Jewish Women in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Brandeis University. Waltham, Massachusetts. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Bruns, Peter. "Een Antilliaans jurist van de wereld". Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Hooi, Elson". National Football Teams. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Voormalig Quick-honkballer Jacoba overleden". RTV Utrecht (in Dutch). 19 December 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Jakoba verstrikt in reglementen". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 27 February 1989. Retrieved 29 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Andruw Jones Stats, Fantasy & News MLB.com". MLB.com.

- ^ "Jonathan Schoop #7". MLB.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Benjamins, Herman Daniël; Snelleman, Johannes (1917). Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië (in Dutch). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.