Tsuu T'ina 145

Tsuu T'ina Nation 145

tsúùtʾínà | |

|---|---|

| Tsuu T'ina Nation Indian Reserve No. 145 | |

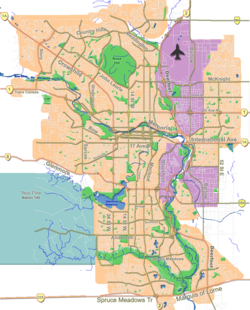

Location of Tsuu T'ina Nation 145 relative to Calgary | |

| Coordinates: 50°58′N 114°21′W / 50.967°N 114.350°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Region | Calgary Region |

| Census division | 6 |

| Government | |

| • Chief | Roy Whitney |

| • Governing body | Tsuut'Ina Nation Council |

| Area | |

• Total | 283.14 km2 (109.32 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,160 m (3,810 ft) |

| Population (2011)[3] | |

• Total | 2,052 |

| • Density | 7.2/km2 (19/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Forward sortation areas | |

| Highways | Highway 22X, Highway 201 |

| Website | tsuutinanation |

Tsuu T'ina Nation 145 (Tsuut'ina: Tsúùtʾínà, lit. 'a great number of people',[4] 'many people'; or 'beaver people'[5]) is an Indian reserve of the Tsuut'ina Nation in southern Alberta, Canada, created by Treaty 7.

The reserve is located in the Calgary Region, bordering the City of Calgary to the northeast, east and southeast, the Municipal District of Foothills No. 31 to the south and Rocky View County to the west and north. It is bound by Tsuut'ina Trail to the east, 146 Avenue SW to the south and Highway 22 and Wintergreen Road (Range Road 52) to the west, while Highway 8 is generally within 0.8 km (0.5 mi) of the reserve's northern boundary.[6] The Hamlet of Bragg Creek is adjacent to the southwest corner of the reserve within Rocky View County across Highway 8.

Demographics

[edit]

In the 2011 Census, Tsuut'ina had a population of 1,777 living in 540 of its 565 total dwellings.[7] Statistics Canada subsequently amended the 2011 census results to a population of 2,052 living in 630 of its 655 total dwellings.[8] With a land area of 283.18 km2 (109.34 sq mi), it had a population density of 7.2/km2 (18.8/sq mi) in 2011.[7][8]

- Population in 2011: 2,052

- Population in 2001: 1,982

- Population in 1996: 1,509

- 1996 to 2001 population change (%): 31.3

- Total private dwellings: 632

- Population density per square kilometre: 7.0

- Land area 283.14 km2 (109.32 sq mi)[2]

Tsuut'ina–municipal, provincial, federal relationships

[edit]Throughout his term as Calgary mayor, Naheed Nenshi met frequently with former Chiefs Roy Whitney, Sandford Big Plume, to discuss matters of mutual assistance with growth.[9] In 2011, the Nenshi and Big Plume negotiated tentative agreements to ensure the security of greater access safety services such as emergency medical services, police, and fire.[10] Chief Whitney mentions that Nenshi's negotiations has warmed relationships and influenced the nation's decision to resume negotiations.[11]

The city agreed to provide utilities such as water to support the expansion of the Grey Eagle Casino to serve as water works and possible extension throughout the Tsuut'ina community in the future.[12][9]

In 2013 Tsuut'ina Police and Calgary Police commenced a professional relationship to cooperate in a joint effort to protect the bordering growing communities. They will share expertise and improve communications. Sgt. Steve Burton, the liaison, will help share his knowledge of criminal psychology as he learns about the Tsuut'ina community.[13]

Historical and contemporary developments

[edit]Glenmore Reservoir claims

[edit]The Tsuut'ina nation and the federal government settled on compensation for the flooding caused by the creation of the Glenmore Reservoir in 1930. The federal government compensated the nation with $20 million in 2013. The compensation was divided by half for the greater community and $5,500 for each member of the tribe.[14]

Grey Eagle Casino

[edit]In 2007, the Tsuut'ina constructed the Grey Eagle Casino outside city limits on land formerly occupied by the Harvey Barracks. The land was ceded back to the nation in 1996 when the lease expired.[15] As of 2014 the casino is exempt from province wide anti-smoking legislation and caters to smoking gamblers. As well, the facility provides clean air for non smoking gamblers via a $2 million air filtration system.[16] According to gambling researcher Gary Smith, the Grey Eagle Casino's proximity to nearby Mount Royal University might cause for concern as an addictive influence among susceptible students. Students might be tempted to spend their leisure time there or enticed to eat there. However, representatives from Grey Eagle and Mount Royal Vice President Duane Anderson, said that the casino had not had a significant influence since opening in 2007. The concern of the expanded casino's influence upon Mount Royal University's student body remains. Mount Royal University's student wellness centre provides information and assistance for students with addictive vices such as gambling.[17][18]

The Grey Eagle Casino began a major expansion, including construction of a hotel, in 2012.[19] However, residents of the neighbouring Lakeview community raised concern for potential increases in traffic.

In 2014, the Grey Eagle Casino underwent a renovation, and a new hotel/conference facility and event centre were added.[20]

Harvey Barracks

[edit]Northern portions of Tsuut'ina land were leased by the Department of National Defence and used to train Canadian Army personnel in live fire operations between 1901–1996. The Harvey Barracks camp, "Camp Harvey", was a 1.5-square-kilometre (380-acre) parcel. The Tsuut'ina Nation resumed sovereignty of Harvey Barracks in 2006 after the Government of Canada conducted de-mining operations for 15 years to dispose of unexploded ordnance, such as artillery projectiles, mortar shells, hand grenades, and live cartridges. Altogether 49 square kilometres (12,000 acres) of land were returned to the Tsuu T'ina Nation.[21][22]

Unexploded ordnance

[edit]In 1986, the Tsuut'ina authorities under the leadership of Chief Roy Whitney took the initiative and founded an ordnance disposal company entitled the "Wolf's Flat Ordnance Disposal Corp". In the 1950s, three Tsuut'ina citizens, a grandmother and her grandchildren, were injured while berry picking. Her grandchild examined an explosive which detonated. The accident prompted the foundation of the service which was named after an honoured elder.[23] The company is expected to flourish as land leases for military bases across North America expire. The company has gained a worldwide reputation and serves countries which suffer from unexploded ordnance on their lands. After decades of extensive ordnance clearance by the company and the Government of Canada, occasionally live ordnance is still discovered. In 2013, a live artillery projectile was uncovered by summer floods.[24]

Black Bear Crossing

[edit]In 1996 Harvey Barracks and Currie Barracks (both part of the former CFB Calgary) were decommissioned and troops stationed at these facilities were reassigned to a base in Edmonton. The Black Bear Crossing area of Harvey Barracks became a neighbourhood within the nation when homeless band members took residence in the 180 vacant Canadian Army housing units en masse as the nation suffered a housing shortage in 1998.[25] Initially they were denied permission by both the Tsuut'ina tribal authorities and by the Department of National Defence whose lease was still effective. There were concerns that asbestos had been used in the insulation of the housing units and there was still unexploded ordnance in the vicinity of the neighbourhood. The Department of National Defence later relinquished control of the area, stating that there was no danger of exposure to asbestos. The area grew into a neighbourhood housing 800 residents and was served by the Tsuut'ina Police.[25] However, in 2006, Health Canada declared the buildings unfit to live in, citing asbestos contamination, and the tribal council ordered the buildings evacuated. The housing units were demolished in 2009.

Ring road

[edit]Alberta Transportation had long pursued the acquisition of lands on the reserve to build a portion of the Calgary ring road, Stoney Trail. The Glenmore Reservoir, which is one of Calgary's sources of drinking water, is a major cause of traffic problems. The ring road connects from about the Sarcee Trail–Glenmore Trail intersection to Alberta Highway 22X, alleviating traffic congestion in the south. The route of this ring road cuts across the corner of the reserve bordering the reservoir.

Opposition to the proposed road came from the environmental community, which did not want major infrastructure built through land considered valuable to a fragile ecosystem. There were discussions on and off regarding commencement of this project since the early 1990s.

The land swap necessary to build the ring road through the reserve was rejected in a referendum by the Nation in 2009, and the City of Calgary announced that alternative plans would put the ring road on municipal and provincial lands only. Negotiations to locate the road on the reserve resumed in 2011.

On October 24, 2013, members of the Tsuut'ina Nation voted in favour of accepting the offer from the Province of Alberta in a referendum to exchange 1.73 square kilometres (428 acres) of nation territory for an expansion of 8.7 square kilometres (2,160 acres) of Crown land. The Nation was compensated with $66 million with relocation assistance and $275 million.[26] Chief Roy Whitney signed the accord with Premier Alison Redford on November 27, 2013. Utilities such as a high pressured gas line and electronic Enmax substation were rerouted along the road route.[26] The decision was difficult as considerations such as relocation troubled the community. Also, according to tribe spokesperson Peter Manywounds, the route would bisect prime agricultural and scenically aesthetic land.[27] He also said that the vague wording of previous attempted agreements contributed to reluctance in the past to agree on negotiations. Chief Roy Whitney anticipated the road would bring development along the route that could benefit the Nation including the Grey Eagle Casino resort development. Residents of Calgary's Lakeview neighbourhood were also relieved as they were troubled for over a decade by the future prospect of their homes along 37 Street, adjacent to the proposed detour, being demolished.[26]

The section of the Southwest Calgary Ring Road passing through the exchanged reserve land was renamed to Tsuut’ina Trail and opened in fall 2020.[28][29]

Taza

[edit]On 28 August 2020, Costco opened its first store on First Nations land at 12905 Buffalo Run Blvd, becoming the first tenant at The Shops at Buffalo Run in the Taza development.[30] Taza will have an area of over 4.9 square kilometres (1,200 acres) and is situated adjacent to Calgary's southwestern border.[31]

Taza is planned to consist of three villages: Taza Park. Taza Crossing, and Taza Exchange.[31] Taza Exchange is the first to open and is the location of The Shops at Buffalo Run.[32]

Recovery centre

[edit]In July 2023, the UCP government signed an agreement with the Tsuu Tʼina pledging $30 million for a 75-bed recovery centre, one of 11 in Alberta First Nations. The facility will have an estimated capacity for 300 people yearly.[33]

Education

[edit]The reserve has three schools: Chiila Elementary School, Chief Big Belly Middle School, and Many Horses High School. They are all operated by Tsuut'ina Education.[34]

References

[edit]- ^ Tsuu T'ina Nation. "Chief and Council Members". Retrieved 2023-06-01.

- ^ a b Statistics Canada (2001 Census). Tsuu T'ina Nation 145 Community Profile

- ^ Statistics Canada. "Corrections and updates:Population and dwelling count amendments, 2011 Census". Revised September 11, 2013. retrieved Dec. 3, 2013

- ^ "Treaty 7 Management – Tsuutʼina Nation (Sarcee)". Treaty7.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "tsuutina.com". Tsuut'ina Nation. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Tsuu T'ina Nation. "Reserve Lands Map".

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. January 30, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ a b "Corrections and updates". Statistics Canada. August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Markusoff, Jason "Time could not be reached for comment: Tsuu T'ina chief on ring road", Calgary Herald, June 17, 2013. retrieved October 26, 2013

- ^ Komarnicki, Jamie. " Chief says ring road 'on the back burner'". Calgary Herald. October 29, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2013

- ^ Komarnicki, Jamie. "Proposed ring road deal stirs heated debate on First Nation" September 19, 2013. Calgary Herald. retrieved ??? 29, 2013

- ^ CBC. "Calgary, Tsuu T'ina". September 19, 2013. CBC News. retrieved October 27, 2013

- ^ Hixt, Nancy and Elliott, Tamara. "Calgary Police, Tsuu T'ina reserve partner up to fight crime". November 12, 2013. Global News Calgary. retrieved December 3, 2013

- ^ CBC News "Tsuu T'ina members get $5,500 settlement cheques". July 22, 2013. CBC News Calgary. retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Tsuu T'ina casino opens amid smoking, traffic concerns". CBC News. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ McIntyre, Doug. "Casino gives smokers nod".[usurped] Sun Media. December 20, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2014

- ^ Mount Royal University. "Compulsive Gambling". retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ Saretsky, Kristine. "Grey Eagle neighbours with University". Calgary Journal, February 18, 2013. retrieved July 3, 2014

- ^ "Tsuu T'ina announces $65M Grey Eagle Casino expansion". CBC News. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "KBM Commercial Flooring | Portfolio Grey Eagle Casino - KBM Commercial". kbmcommercial.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ CBC News. "Military returns land near Calgary to First Nation". July 31, 2006. CBC News:Calgary. retrieved December 11, 2013

- ^ "Military returns land to Calgary aboriginal band: after 15 years of removing century-old shrapnel, the government has finally returned a former military training ground back to Calgary Tsuu T'ina nation". July 30, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2013

- ^ Paquette, Donna-Rae. "Business exploding on southern First Nation". Volume 16. Issue 4, 1998. Windspeaker. retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ Gandia, Renato. "Live Howitzer Shell Flushed Out by Calgary Flood". July 3, 2013, Calgary Sun. retrieved June 7, 2014

- ^ a b Klaszuz, Jeremy. "The battle for black bear crossing". October 30, 2008. Fast Forward Weekly. retrieved December 12, 2013

- ^ a b c CBC News. "S.W. ring road deal approval 'historical', says Tsuu T'ina chief". October 25, 2013. CBC News Calgary. retrieved November 2013

- ^ CBC News. "Tsuu T'ina says ring road beneficial for future generations". October 28, 2013. CBC News Calgary. retrieved November 29, 2013

- ^ "Decades in the making, southwest ring road from Highway 8 to Fish Creek Boulevard to open to traffic". calgaryherald. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Dippel, Scott (May 22, 2020). "Key part of southwest ring road on track to open this fall, not 2021". CBC News. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ White, Ryan (2020-08-28). "Costco opens on Tsuut'ina Nation, company's first store on an Indigenous development in Canada". CTV News. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b "Home". Taza. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ "Home". Taza Exchange. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Heintz, L. (Jul 5, 2023) 'Alberta partners with Tsuut'ina Nation on 75-bed recovery facility', City News, retrieved from https://calgary.citynews.ca/2023/07/05/alberta-tsuutina-nation-recovery-facility/, retrieved on Jul 6, 2023.

- ^ "Tsuut'ina Education". Tsuut'ina Education. Retrieved 2022-08-18.