River Market, Kansas City

River Market | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood | |

A City Market farmers' market entrance is at Walnut Street & West 5th Street | |

| |

| Coordinates: 39°06′45″N 94°35′03″W / 39.112414°N 94.58413°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Jackson |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 1,345 |

| Website | thecitymarketkc |

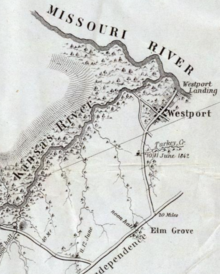

The River Market (formerly known as Westport Landing, the City Market, and River Quay) is a riverfront neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri that comprises the first and oldest incorporated district in Kansas City. It stretches north of the downtown Interstate 70 loop to the Missouri River, and is bordered by the Buck O'Neil Bridge on the west and the Heart of America Bridge on the east. As of September 2018[update], the population was 1,345.[1]

History

[edit]

Founding and early development

[edit]Starting in 1821, the area was an early French fur trading post operated by François Chouteau of the powerful Chouteau clan. The name "Westport Landing" is derived from having been the dock on the Missouri River for the exchange of goods destined for the community of Westport three miles to the south on higher ground that was operated by John Calvin McCoy. He was to lead a group of settlers to create the Town of Kansas in this location in 1850 which in turn became the City of Kansas in 1853. This made it the first and oldest incorporated district in what is now Kansas City.

In the mid 1800s, the first courthouse, police headquarters, and city hall were all located in what became the southern section of City Market, a large farmers' market and center of commercial activity in the area.[2] Notable locations during this period in River Market history include the Pacific House Hotel, originally erected in 1860. During the Civil War, the hotel was occupied by Union Troops, and from there General Ewing issued General Order No. 11, which forced residents to evacuate key rural areas in Missouri in order to deprive Confederate fighters of material support. Jesse James also resided at the Pacific House hotel,[3] and Wyatt Earp enjoyed vacationing in the area and spending time in the River Market with Thomas Speers, Kansas City's first town marshal.[2]

The first streetcar line in Kansas City, originally launched in 1870 as a horse-drawn carriage line, began at Fourth and Main streets in City Market and ran to Westport. The route was converted to cable rail in 1887.[4] In 1880, the Centropolis Hotel (named after what William Gilpin proposed as the name for Kansas City itself) was built at 5th Street and Grand Avenue in City Market. It was the first hotel in the city to boast electric lighting and became a popular dinner destination for theater-goers in the area.[5]

Kansas City Jazz era and decline

[edit]In the 1910s, Tom Pendergast purchased the Jefferson Hotel near the City Market. For a decade, the building served as the headquarters for his "Goats" political faction. With Kansas City rapidly expanding to the east and south, the River Market area began to be referred to as "Old Town" at this time, because it was seen as a remnant of an older time of licentiousness. Under Pendergast's control, it was known for late-night drinking, gambling, cabaret, and prostitution. It was populated by those considered to be on the lowest end of the socio-economic spectrum by more upper-class Kansas Citians, including Italians, Jews, Irish, Native and Black Americans.[6] The neighborhood was home to three of the most notorious brothels in the city, all owned by women: Madame Lovejoy, Eva Prince, and Annie Chambers (née Leannah Kearns). Chambers built her brothel at Third and Wyandotte Street, where it operated daily until 1913, and continued to operate until 1924, backed by Pendergast, despite a citywide anti-prostitution crackdown.[7]

Between 1931 and 1939, a row of buildings was erected in the City Market as part of Pendergast's "Ten-Year Plan" to create jobs lost during the Great Depression.[8] Since then, these buildings have supported a Saturday farmer's market, as well as the other restaurants and businesses that comprise City Market.[3] However, as the center of commerce in Kansas City continued to shift south, the River Market area began to decline in importance. The Centropolis Hotel was demolished in 1941, now serving as a parking lot for City Market customers.[5]

1970s River Quay revitalization and mob violence

[edit]In 1971, Rockhurst University professor Marion A. Trozzolo began redeveloping historic buildings on the riverfront and nicknamed the area River Quay. In contrast to its long-standing reputation for organized crime and other illicit activity, Trozzolo envisioned the revitalized River Quay as a family-friendly commercial district. With the increase of popular shops, restaurants, and attractions, the city began a marketing campaign for shoppers, with free shuttle bus rides from downtown. In 1972, Fred Bonadonna, son of an organized crime member connected to the operations of Nicholas Civella, was allowed to open a restaurant in the River Quay. Tensions between Bonadonna's desire to follow Trozzolo's family-friendly vision for the River Quay and the mob's desire for adult establishments led to the murder of Bonadonna's father, and a series of bombings that destroyed two bars.[9] This and other mob violence ended Trozzolo's River Quay revitalization project.[10]

Since 2000s

[edit]The large riverfront warehouses have become increasingly developed into residential lofts, restaurants, bars, shops, cafes, and ethnic markets. Since its inception in 1857, the City Market has been one of the largest and most enduring public farmers' markets in the Midwest, linking growers and small businesses to the Kansas City community. More than 40 full-time independently owned shops and restaurants are open year-round. The farmers' market features local vendors every weekend. The Arabia Steamboat Museum at 400 Grand Blvd. is a tourist attraction displaying thousands of artifacts from a steamboat and its cargo that had sunk nearby in 1856 and was recovered in 1987–88.

KC Commercial Realty Group manages the market on behalf of the City of Kansas City. The official neighborhood association for the River Market neighborhood is the River Market Community Association.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Population of River Market, Kansas City, Missouri (Neighborhood)". September 14, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Little, Leigh Ann; Olinskey, John M. (2013). Early Kansas City, Missouri. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9096-7.

- ^ a b American Institute of Architects. Kansas City Chapter (2000). The American Institute of Architects guide to Kansas City architecture and public art. Internet Archive. Kansas City : American Institute of Architects/Highwater Editions. ISBN 978-1-888903-06-5.

- ^ Dodd, Monroe (2002). A Splendid Ride: The Streetcars of Kansas City, 1870-1957. Kansas City Star Books. ISBN 978-0-9722739-8-5.

- ^ a b Dodd, Monroe (2003). Kansas City Then and Now II. Kansas City Star Books. ISBN 978-0-9740009-1-6.

- ^ Reddig, William M. (1986). Tom's Town: Kansas City and the Pendergast Legend. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-0498-1.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas Morris (2004). The Other Missouri History: Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6430-5.

- ^ Luchene, Katie Van (May 18, 2010). Insiders' Guide® to Kansas City. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7627-6338-2.

- ^ United States Congress Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (1989). Organized Crime and Use of Violence: Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, United States Senate, Ninety-sixth Congress, Second Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Isenberg, Alison (May 15, 2009). Downtown America: A History of the Place and the People Who Made It. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-38509-9. Retrieved October 8, 2023.