Speed Freak Killers

Loren Herzog | |

|---|---|

Mugshot | |

| Born | Loren Joseph Herzog December 8, 1965[2] Linden, California, U.S. |

| Died | January 16, 2012 (aged 46)[3] Susanville, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (4 counts, overturned) Voluntary manslaughter Accessory to murder (3 counts) Furnishing amphetamine |

| Criminal penalty | 78 years (overturned) 14 years, paroled after 11 years |

| Details | |

| Victims | 4–19+[1] |

Span of crimes | November 27, 1984 – November 18, 1998 (Confirmed) |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

Date apprehended | March 17, 1999 |

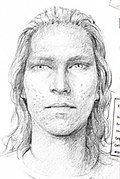

Wesley Shermantine | |

|---|---|

Mugshot | |

| Born | Wesley Howard Shermantine, Jr. February 24, 1966[4] Linden, California, U.S. |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (4 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 4–19+[1] |

Span of crimes | November 27, 1984 – November 18, 1998 (Confirmed) |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California, Utah |

Date apprehended | March 17, 1999 |

The Speed Freak Killers is the name given to serial killer duo Loren Herzog and Wesley Shermantine, together initially convicted of four murders — three jointly — and suspected in the deaths of as many as 72 people in and around San Joaquin County, California, based on a letter Shermantine wrote to a reporter in 2012.[5] They received the "speed freak" moniker due to their habitual methamphetamine abuse. Herzog committed suicide in 2012. Shermantine remains on death row in San Quentin State Prison, in San Quentin, California.[6]

Background and investigation

[edit]Loren Joseph Herzog (December 8, 1965 — January 16, 2012) and Wesley "Wes" Howard Shermantine Jr. (born February 24, 1966) grew up in the town of Linden, California, and lived on the same street. Both boys were friends with one another because there were not many other children in their neighbourhood to play with, and it appears that they did not have any other friends throughout high school and into adulthood. Shermantine's father was a successful local contractor and real estate developer who frequently "spoiled" Wesley with gifts and money throughout his life.[7]

Shermantine and Herzog were both avid hunters and fishermen who spent much of their childhood exploring the San Joaquin County countryside. They graduated from Linden High School in 1984 and took pleasure in bullying other people, drinking alcohol, and using drugs, especially methamphetamine, in their apartment in nearby Stockton, California.

During this time, Herzog had a brief affair with a young woman named Kim Vanderheiden. The citizens of Linden, a small town with fewer than 2,000 people, 95 miles east of San Francisco, were long aware of the duo's reputation as methamphetamine users and also knew them as regulars at the Linden Inn bar, which was owned by Kim's father.

Kim's 25-year-old sister, Cyndi Vanderheiden of Clements, California, went missing after leaving the Linden Inn with Herzog and Shermantine on November 14, 1998. Investigation into Vanderheiden's disappearance continued into 1999, Shermantine as the prime suspect. In mid-January 1999, Shermantine's car was repossessed and subsequently searched by the San Joaquin Sheriff's Department. Cyndi Vanderheiden's blood was discovered in the car, and while DNA test results were being confirmed, the sheriff's department focused on Herzog, Shermantine's friend and suspected accomplice who was extensively questioned.

Herzog ultimately divulged incriminating details such as describing how Shermantine had shot a hunter they ran into while on vacation in northern Utah in 1994. Utah police confirmed that a hunter had indeed been killed, but his murder was still classified as unsolved. Herzog also said Shermantine was responsible for killing Henry Howell, 41, who was shot dead and found parked off the road on Highway 88 in Alpine County near Hope Valley with his teeth and head bashed in. Herzog said he and Shermantine passed Howell parked on the highway, and Shermantine stopped, grabbed Howell's shotgun, killed him, and stole what little money he had.

Additionally, Herzog gave specific details about how Shermantine killed Robin Armtrout, 24, whose nude body was found stabbed nearly a dozen times on the east bank of Potter Creek near Linden. Herzog and Shermantine were arrested by the San Joaquin County Sheriff's Department and charged with several counts of murder each on March 17, 1999.[8]

Convictions

[edit]In 2001, a jury found Shermantine guilty of four murders: those of Vanderheiden, the robbery-murder of drifters Howard King, 35, and Paul Raymond Cavanaugh, 31, whose bodies were found shot to death in a car off a remote road on Roberts Island on November 27, 1984, and 16-year-old Chevelle "Chevy" Wheeler, who disappeared in 1985 from Franklin High School in Stockton after telling friends she was leaving school to go with Shermantine to his family's cabin in San Andreas.[9]

During his trial, numerous witnesses testified that they had been brutalized by Shermantine. He was accused of severely raping or sodomizing five different women, including a babysitter who claimed she was attacked when she went to get money he owed her. Shermantine's sister disclosed that she had been also sexually assaulted by the two.[citation needed] One woman claimed that after rear-ending her car, he held her hostage with a knife when she pulled over to exchange insurance information. She leaped out of his moving vehicle and made it to safety. Shermantine's ex-wife also spoke of how he had abused her severely for years, even while she was pregnant and held their kids in her lap. Shermantine was sentenced to death and is on death row at San Quentin State Prison.

Herzog was charged with five counts of murder in 1999: those of Vanderheiden, Howell, Cavanaugh, Armtrout and King.[10] In his 2001 trial, a jury found him guilty on three murder counts (Vanderheiden, Cavanaugh, and King), the lesser charge of accessory to murder in the Howell count, and acquitted him on the Armtrout count.[11] Herzog was given a 78-year sentence.

Appeals and overturned convictions

[edit]An appeals court overturned all of Herzog's convictions in August 2004, ruling that three of Herzog's four confessions were coerced.[12] In the case of the fourth, that of Vanderheiden, a retrial was ordered. This retrial never took place. Rather, a plea bargain was reached, and Herzog pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and furnishing amphetamine in the Vanderheiden case and to being an accessory to murder in the Cavanaugh, King, and Howell cases. Accordingly, Herzog's sentence was reduced to 14-years, with credit for six years served.[12] With credit off his sentence for good behavior, Herzog served 11-years in prison and was in a position to be paroled by 2010.

Opposition to the inevitability of Herzog's parole was extremely vocal, especially from victims' families.[13] That no California county wanted to take him for parole led the California Department of Corrections to parole him to a trailer stationed outside the front gate of the High Desert State Prison in Susanville, California in Lassen County in September 2010.[14][15]

Herzog committed suicide in January 2012, hanging himself inside his trailer.[13] He did so shortly after bounty hunter Leonard Padilla informed Herzog that Shermantine was planning to disclose the location of a well and two other locations where the duo buried their victims. Previously, none of their victims' bodies had been found. Both men had maintained that the other did the killing in all cases and emphatically denied any culpability.[16]

Discovery of victims' remains

[edit]Linden, California well

[edit]In February 2010, while Shermantine waited on death row, his sister Barbara received letters from him identifying the locations of victims in an abandoned well on Flood Road near Linden, California. She turned these letters over to the San Joaquin County Sheriff's Department. The Sheriff's Department followed up on the lead, but in an interview with the property owner, the owner stated that the wells in question were sealed before the victims disappeared. No further action was taken at that time.[17]

More came about in February 2012, based on bounty hunter Padilla's promise to pay Shermantine $30,000 for information.[18] A map drawn by Shermantine and additional information given again led authorities to the same Linden, California well site that he had mentioned in 2010. More than 1,000 human bone fragments were recovered. The bones were tested by the California Department of Justice for DNA profiling.[19] In March 2012, the FBI's Evidence Recovery Team was asked to assist with the overall investigation, in part because of how the excavation of the Linden well was handled.[20] The identity of the remains recovered in the well was announced to the public on March 30, 2012. They were those of two Stockton, California teens missing since the mid-1980s: Kimberly Ann Billy, 19, and Joann Hobson, 16. The remains of an additional victim and an unidentified fetus were found in the well.[21]

Former Shermantine property

[edit]Two separate burial sites in Calaveras County, California were investigated in February 2012 based on a letter Shermantine wrote to Padilla that detailed possible locations of victims.[22] Shermantine indicated sites near property formerly owned by Shermantine's parents.[22] Bodies from these two sites were recovered, an unidentified body and Vanderheiden. No additional remains were discovered.

September 2012 burial sites

[edit]Shermantine was briefly released from death row into police custody in September 2012 to lead authorities to four additional abandoned wells where he stated more victim remains would be found, all near the town of Linden, done because Padilla had paid Shermantine an additional $28,000. In early January 2013, the FBI began excavating a well site, which they hoped would yield more victims' remains.[1] Shermantine declined to speak further to authorities. On February 22, 2013, the FBI announced that it had ended the search for victims based on Shermantine's information. Two sites he had indicated had turned up nothing, and "other directions from him were misguided".[23] Shermantine also claimed to know the locations in the Cow Mountain Recreation Area of bodies of victims killed by other death row inmates. Lake County sheriffs were skeptical that any bodies could be successfully recovered in the large park so no searches were conducted.[24]

Allegations of investigation-hampering

[edit]Since 2012, several victims' families and elected officials have alleged that the San Joaquin County Sheriff's Office (SJCSO) interfered with and deliberately hampered the continued search for additional possible victims of the "Speed Freak Killers."[25] In 2010, Shermantine wrote a letter to California State Senator Cathleen Galgiani revealing the locations of the remains of additional victims.[26] In 2012, Galgiani sponsored the use of taxpayer funds to search for additional victims of the pair and sought to simplify protocol granting incarcerated persons like Shermantine permission to participate in search excursions.[26] Galgiani turned the letter over to law enforcement and later alleged that missing person records related to the "Speed Freak Killers" case had been deleted, hampering the further investigation.[27]

In 2014, the mother of a missing woman filed suit against the SJCSO for mishandling the remains found in the Linden well.[28] In 2015, a retired FBI agent corroborated her claims, alleging that the SJCSO deliberately used a backhoe to dig up remains, mangling them to prevent identification, so that the absence of certain files would not be discovered.[25] In 2018, the Sheriff-elect of San Joaquin County announced that the "Speed Freak Killers" case would be re-opened.[29]

Victims

[edit]The total number of mutual victims of Herzog and Shermantine remains unknown and speculative. Both were convicted in the murders of four people and are believed to be responsible for the deaths of at least 19 people. Both men targeted random victims and killed for "fun and sport". They would go out "hunting," shooting individuals to death and, in some cases, kidnapping women, raping them, and stabbing them to death. Afterwards, in Calaveras County, they would dispose of their dead bodies in mine shafts, isolated hillsides, and beneath trailer parks. Prior to his arrest, Shermantine frequently told relatives and acquaintances that he had "made people disappear" around the outskirts of Stockton.[30]

In a confrontation with one woman he tried to rape in a trailer park, Shermantine allegedly told her after he had pushed her head to the ground: "Listen to the heartbeats of people I've buried here. Listen to the heartbeats of families I've buried here." Shermantine stated there could have been up to 72 victims in a statement he sent to a local Sacramento news station in March 2012. Yet he asserted that he would withhold the information unless Leonard Padilla gave him the $33,000 he demanded. "I really want to believe in Leonard, but I have these doubts he'll come through, which is a shame because I've been holding the best for last," Shermantine wrote.[31] The following is a list of their known victims and several other missing people who have been mentioned as possible victims:

- 16-year-old Ruth Ann Leamon disappeared from Modesto, California in 1982 after she became acquainted with two men, both in their thirties, on August 19. Three blocks from her house, at Teresa Street and Carver Road was where Leamon decided to meet the men later that evening. She left her Clayton Avenue apartment that day about 8:45 p.m. She said she was travelling on foot to Sam's Food City to get a soda. In reality, Ruth did show up at the shop, but she quickly left and was never again seen. The two men who were supposed to meet Ruth the night she disappeared were questioned by authorities, but both of them denied any involvement in her case. Herzog and Shermantine are thought to be suspects in Ruth's case. Ruth and a female acquaintance travelled to the Calaveras County Frog Jump with Herzog before she vanished.[32][33]

- According to Herzog, he and Shermantine were driving a truck on September 1, 1984, along Highway 88 in Hope Valley, California, several miles south of Lake Tahoe and west of the Nevada border in a remote location, when they passed a vehicle parked on the side of the road. The vehicle's driver, Henry Lee Howell, 41, from Santa Clara, California had pulled to the side of the road because he was intoxicated. Shermantine stopped his truck, got out, and allegedly shot Howell with a shotgun.

- Two months after the murder of Howell, on November 27, 1984, Herzog and Shermantine were out driving around together again on Roberts Island, California located just southwest of Stockton, when they passed a parked 1982 Pontiac. Herzog told detectives that they turned around, approached the car and grabbed their shotguns as they exited the truck. Herzog said that Shermantine shot and killed the driver, Howard Michael King III, 35, while he sat behind the wheel, and then dragged the passenger, Paul Raymond Cavanaugh, 31, out the passenger door and shot him at point-blank range. The tire tracks found at the scene were eventually revealed to match Shermantine's vehicle, which was the red pickup truck that witnesses later claimed to have seen in the vicinity of Roberts Island before King and Cavanaugh were killed.

- Kimberly Ann Billy, 19, disappeared from Stockton, California on December 11, 1984. 16-year-old Joann Hobson disappeared from Stockton on August 29, 1985. In February 2012, acting on Shermantine's directions, authorities found over 300 human bones and some personal items in an abandoned well in Linden, California. Billy's bones were in the well, as well as those of Hobson.

- On September 8, 1985, Herzog and Shermantine met Roberta Ray “Robin” Jones Armtrout, 24, at a park in Stockton. They were supposed to go out drinking together, but instead they headed to a farm close to Linden, not far from where both men lived. Shermantine "got carried away" at some point and started raping and beating Armtrout. After stabbing her more than a dozen times, he dumped her naked body on the bank of Potter Creek. Investigators noticed that most of the stab wounds were in the back and chest regions when a dove hunter subsequently discovered her naked body. Her mother last saw Armtrout getting into a red pickup truck with the two men.

- Chevelle Yvonne "Chevy" Wheeler, 16, skipped school on Wednesday, October 16, 1985, and was last seen getting into a red pickup truck outside Franklin High School in Stockton. She had told a friend that she was going with a male acquaintance named "Wes" to Valley Springs, California. She asked her friend to tell her father about what she had done if she did not return by the end of the school day because she appeared hesitant about making the trip. The friend did inform her father when Chevy did not show up, and her father then called the police. Shermantine was instantly identified by authorities as the prime suspect since he was familiar with the Wheeler family. Shermantine was found to be the owner of a red pickup truck. Blood and hair samples taken from a cabin Shermantine owned in San Andreas matched Wheeler.

- Susan Robin Bender, 15, left her family's home in Modesto on April 25, 1986, to stay with friends in Carmel, California. She was last observed making a phone call at the former Greyhound bus depot on 10th Street and G Street in Modesto. Susan was seen entering a full-sized, olive-green 1977 Ford van outside of the station and has never been seen again. Authorities investigated Herzog and Shermantine as possible suspects in 2012 but were unable to find a link. Foul play is suspected in her case.[34]

- On June 3, 1986, 31-year-old Sylvia Lourdes Standly disappeared from Modesto, California. She was released from the Stanislaus County Women's Facility on Oakdale Road that day and then called her family and said she would get a ride home. She was last seen getting into a blue or green truck. Her case remains unsolved.[35]

- Gayle Marie Marks, 18, accompanied her mother to the San Joaquin County Mental Health Department in Stockton, California on October 18, 1988. Marks then walked alone to the local DMV on Parks Street to get an identification card. She made it to the DMV because a few days later, her card was mailed to her address. After leaving the DMV, Marks contacted her mother and left a message. She has never been heard from again. Shermantine and Herzog were investigated in relation to her case in 2012.[36]

- 47-year-old Phillip Cabot Lloyd Martin was a transient who was last seen in north Stockton, California on September 30, 1993. On that day, he forgot to pick up his daughters from school, and no one has seen or heard from him since. Martin's daughter told authorities that her father had worked with Shermantine, and that as a young girl, she had chosen him from a line-up of pictures. His daughter said she believed Martin, Shermantine and Herzog used drugs together. Martin's case remains unsolved.[37]

- Tracy Diane Melton, 32, disappeared from Stockton, California on May 6, 1998. A bone fragment located in Linden, California in 2003 was identified as hers in April 2011, but her family was not notified until January 2012. Evidence pointed to Shermantine and Herzog as suspects. Vanderheiden, who was killed by the pair, vanished a few months after Melton, and detectives have never ruled out the pair in Melton's case.[38]

- Cynthia Ann “Cyndi” Vanderheiden, 25, disappeared from Clements, California on November 14, 1998. In 1999, Herzog and Shermantine were charged together with her murder as well as other deaths. Vanderheiden's skull was found in a ravine in San Andreas, California in February 2012.

Connection to Garecht disappearance

[edit]In August 2012, Shermantine wrote a letter to The Stockton Record after Herzog committed suicide in January 2012, in which he pointed out that Herzog bore a resemblance to the composite of the person who kidnapped "that Hayward girl."[39] Commenting on the likeness Herzog bore to Garecht's kidnapper, witness Katrina Rodriguez commented: "I thought then and I think now he could be the kidnapper... I think there are features that look very much like the man...It seems like a strong lead."[39]

At Shermantine's direction, law enforcement began excavating an abandoned well in rural Linden, California in February 2012,[40] where Herzog and Shermantine disposed of their victims.[41] Thousands of bone fragments belonging to five different individuals[40] were recovered from the well, some of which were believed to potentially belong to Garecht.[41] However, DNA profiling completed later that year excluded Garecht as a possibility; the bones believed to have been hers were determined to be those of 19-year-old Kimberly Billy, who had disappeared in 1984.[41] In January 2013, further excavations of abandoned wells in the area were completed, but yielded no further remains.[40]

In 2015, a legal motion was filed by attorney Mark Geragos[42] on behalf of a detective who was informed by a San Joaquin sheriff's deputy that a pair of Mary Jane shoes discovered in one of the Linden wells bore similarity to the shoes Garecht was last seen wearing.[43] According to the detective, San Joaquin police refused to show him the shoes, both physically as well in photographs, and the shoes had not been examined by the Hayward Police Department.[43] In December 2020, suspected serial killer David Emery Misch was arrested for Garecht's murder after he was linked to the crimes via fingerprints left on Michaela's scooter at the abduction site.[44]

In popular media

[edit]This case was featured on episode 178 of the series American Justice, "Vanished", which first aired September 4, 2002.[45] With the episode's 2002 production date, newer details relating to this case were not a part of the program. Two of the victims' families (the Wheelers and Vanderheidens) did not yet know where their daughters' bodies were, and Herzog was still serving a 78-year sentence.

In 2013, popular British true crime television program Born to Kill? made an episode about the pair. The story was covered on the 2015 episode “Where Evil Lives”, on the crime documentary series On the Case with Paula Zahn. The episode included updates on Herzog's release and suicide, and the discovery of victims’ remains, including Wheeler and Vanderheiden—with comments from Wheeler's and Vanderheiden's families. In 2022, a Parcast production titled ‘Serial Killers’ chronicled the murders and lives of both Herzog and Shermantine in an episode titled ‘Speed Freak Killers’.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "FBI digging up Calif. well looking for more "Speed Freak Killers" victims". CBS News.

- ^ California Births, 1905 - 1995, Loren J. Herzog

- ^ "Speed Freak Killer's cause of death, deep anger revealed". The Mercury News. March 6, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ California Births, 1905 - 1995, http://www.familytreelegends.com/records/39461?c=search&first=Wesley&last=Shermantine Wesley H. Shermantine

- ^ "'Speed Freak Killer' Claims Dozens Of Victims". Sky News. October 1, 2012.

- ^ Phillips, Roger (March 4, 2019). "Public defender requests preservation of evidence in Shermantine case". The Modesto Bee. p. A3.

- ^ The Speed Freak Killers (Born To Kill), Youtube

- ^ "The Grisly Story Of The 'Speed Freak Killers' Who Terrorized California For Two Decades". All That's Interesting. April 27, 2022.

- ^ "'Speed Freak Killers' Update: Search for victims' remains reaches the bottom of Calif. well". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012.

- ^ "Four additional murder counts filed against Loren Herzog". Lodinews.com. March 23, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Writer, Linda Hughes-Kirchubel Record Staff. "Jury finds Herzog guilty". recordnet.com. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Convicted killer Loren Herzog commits suicide". Lodinews.com. January 17, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Paroled killer Loren Herzog found hanged in his trailer at prison". LA Times Blogs - L.A. NOW. January 17, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Scott. "Lassen County loses Herzog parole appeal". recordnet.com. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "Loren Herzog, Half of "Speed Freak Killers" Duo, to be Freed on Parole". www.cbsnews.com. September 13, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Wollan, Malia (February 18, 2012). "Serial Killers' Graveyard Opens California Town's Wounds". The New York Times.

- ^ "Speed Freak Killer's Sister Says Police 'Dropped The Ball' On Her Tips". October 26, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ ""Speed Freak Killers" Update: FBI excavating another well for possible victims". CBS News. January 8, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "'Speed Freak Killer' Speaks Out In Letter, Search Enters 2nd Week". cbslocal.com. February 17, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ "FBI Asked To Assist In Search For Victims Of 'Speed Freak Killers' « CBS Sacramento". cbslocal.com. March 2, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ "Two Victims From Linden Well Identified In 'Speed Freak Killers' Case". March 30, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Coverage Of Shermantine Property Search". KCRA 3. KCRA-TV. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ "Search For Victims Of 'Speed Freak Killers' At An End". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "'Speed freak killer' hints at 14 bodies near Clear Lake". mercurynews.com. July 25, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Speed Freak Killers case: Retired FBI agent alleges San Joaquin Sheriff's Office sabotaged crime scene". The Mercury News. March 14, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "State Sen. Cathleen Galgiani: 'Speed Freak Killers' records deleted". Lodinews.com. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Speed Freak Killers investigators stymied kidnap probe, suit says". SFGate. March 10, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ SCOTT SMITH. "Mom says county 'pulverized' Calif. girl's remains". sandiegouniontribune.com. Associated Press. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Meza, Melinda (September 7, 2018), Sheriff-elect reopens Speed-Freak killers case in San Joaquin County, retrieved October 8, 2018

- ^ Montaldo, Charles, Wesley Shermantine and Loren Herzog, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ Speed Freak Killers: Victims And Possible Victims, February 13, 2012, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ Ruth Ann Leamon, The Charley Project

- ^ 319DFCA, The Doe Network

- ^ Case of missing California teen Susan Bender re-opened 36 years later, October 12, 2021, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ The Charley Project: Sylvia Lourdes Standly, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ Questions Remain For Families Of Potential 'Speed Freak' Victims After FBI Meeting, April 17, 2013, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ Pelisek, Christine (July 19, 2012), "'Speed Freak Killer' Wesley Shermantine to Help Police Find Victims", The Daily Beast, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ California Family Notified 9 Months After Missing Woman Remains Identified, retrieved April 1, 2023

- ^ a b Brinkley, Leslie (February 1, 2012). "New lead in Michaela Garecht kidnapping case". ABC 7 News. San Francisco, California. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c "FBI Abandons Dig Of Linden Well After Coming Up Empty". CBS 13. Sacramento, California. February 21, 2013. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c "DNA Results Of Commingled Remains Of Speed Freak Killers' Victims Released". CBS Sacramento. Sacramento, California. January 9, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Henry K. (March 10, 2015). "Speed Freak Killers investigators stymied kidnap probe, suit says". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Gafni, Matthias (March 9, 2015). "Michaela Garecht disappearance: Speed Freak Killers information allegedly withheld by sheriff's office". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Michaela Garecht Cold Case: Convicted Killer David Misch Charged With Her Kidnapping, Murder". CBS San Francisco (in Luxembourgish). December 21, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ TV.com. "American Justice". TV.com. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

External links

[edit]- 2001 in California

- 2012 in California

- 20th-century American criminals

- American male criminals

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- Serial killer duos

- Methamphetamine in the United States

- People convicted of murder by California

- People from Linden, California

- Serial killers from California