Tafamidis

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vyndaqel, Vyndamax, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.246.079 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

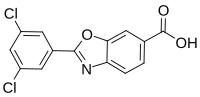

| Formula | C14H7Cl2NO3 |

| Molar mass | 308.11 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Tafamidis, sold under the brand names Vyndaqel and Vyndamax,[5] is a medication used to delay disease progression in adults with certain forms of transthyretin amyloidosis. It can be used to treat both hereditary forms, familial amyloid cardiomyopathy and familial amyloid polyneuropathy, as well as wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis, which formerly was called senile systemic amyloidosis. It works by stabilizing the quaternary structure of the protein transthyretin. In people with transthyretin amyloidosis, transthyretin falls apart and forms clumps called (amyloid) that harm tissues including nerves and the heart.[6][7]

The US Food and Drug Administration considers tafamidis to be a first-in-class medication.[8]

Medical use

[edit]Tafamidis is used to delay nerve damage in adults who have transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy, or heart disease in adults who have transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy.[4][5][7][9] It is taken by mouth.[4][5]

Women should not get pregnant while taking it and should not breastfeed while taking it. People with familial amyloid polyneuropathy who have received a liver transplant should not take it.[4]

An alternative treatment is acoramidis.

Adverse effects

[edit]More than 10% of people in clinical trials had one or more of urinary tract infections, vaginal infections, upper abdominal pain, or diarrhea.[4]

Interactions

[edit]Tafamidis does not appear to interact with cytochrome P450 but it inhibits ATP-binding cassette super-family G member 2, so is likely to affect the levels of certain drugs including methotrexate, rosuvastatin, and imatinib. It also inhibits organic anion transporter 1 and organic anion transporter 3/solute carrier family 22 member 8 so is likely to interact with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and other drugs that rely on those transporters.[4]

Pharmacology

[edit]Tafamidis is a pharmacological chaperone that stabilizes the correctly folded tetrameric form of the transthyretin protein by binding in one of the two thyroxine-binding sites of the tetramer.[9] In people with familial amyloid polyneuropathy, the individual monomers fall away from the tetramer, misfold, and aggregate; the aggregates harm nerves.[9]

The maximum plasma concentration is achieved around two hours after dosing; in plasma it is almost completely bound to proteins. Based on preclinical data, it appears to be metabolized by glucuronidation and excreted via bile; in humans, around 59% of a dose is recovered in feces, and approximately 22% in urine.[4]

Chemistry

[edit]The chemical name of tafamidis is 2-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-1,3-benzoxazole-6-carboxylic acid. The molecule has two crystalline forms and one amorphous form; it is manufactured in one of the possible crystalline forms. It is marketed as a meglumine salt. It is slightly soluble in water.[10]

History

[edit]The laboratory of Jeffery W. Kelly at The Scripps Research Institute began looking for ways to inhibit transthyretin fibril formation in the 1990s.[11]: 210 Tafamidis was eventually discovered by Kelly's team using a structure-based drug design strategy; the chemical structure was first published in 2003.[12][13][14] In 2003, Kelly co-founded a company called FoldRx with Susan Lindquist of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Whitehead Institute,[14][15] and FoldRx developed tafamidis up through submitting an application for marketing approval in Europe in early 2010.[13] FoldRx was acquired by Pfizer later that year.[13]

Tafamidis was approved by the European Medicines Agency in November 2011, to delay peripheral nerve impairment in adults with transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis.[9] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration rejected the application for marketing approval in 2012, on the basis that the clinical trial did not show efficacy based on a functional endpoint, and requested further clinical trials.[16] In May 2019, the FDA approved two tafamidis preparations, Vyndaqel (tafamidis meglumine) and Vyndamax (tafamidis), for the treatment of transthyretin-mediated cardiomyopathy.[7] The drug was approved in Japan in 2013; regulators there made the approval dependent on further clinical trials showing better evidence of efficacy.[17]

The FDA approved tafamidis meglumine based primarily on evidence from a clinical trial of 441 adult patients conducted at 60 sites in Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Spain, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Great Britain, and the United States.[18]

There was one trial that evaluated the benefits and side effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, in which patients were randomly assigned to receive either tafamidis (either 20 or 80 mg) or placebo for 30 months.[18] About 90% of patients in the trial were taking other drugs for heart failure (consistent with the standard of care).[18]

The European Medicines Agency designated tafamidis an orphan medicine[6] and the Food and Drug Administration also designated tafamidis meglumine as an orphan drug.[19]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]Tafamidis was approved in the European Union in 2011 for the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy, and in Japan in 2013.[6][17] In the United States, it was rejected for the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy because the Food and Drug Administration saw insufficient evidence for its efficacy.[20][7]

Tafamidis can also be used to treat transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy. It was approved for the treatment of this form of the disease in the United States in 2019 and in the European Union in 2020. In the United States, there are two approved preparations: tafamidis meglumine (Vyndaqel) and tafamidis (Vyndamax).[7][21][18] The two preparations have the same active moiety, tafamidis, but they are not substitutable on a milligram to milligram basis.[7]

Tafamidis (Vyndamax) and tafamidis meglumine (Vyndaqel) were approved for medical use in Australia in March 2020.[22]

Tafamidis is available in a total of 64 countries.[23]

Economics

[edit]Pfizer reported revenue of US$3.321 billion for Vyndaqel in 2023.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Vyndamax and Vyndaqel Australian prescription medicine decision summary". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 17 July 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Vyndaqel". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Vyndaqel 20 mg soft capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics". Electronic Medicines Compendium. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Vyndaqel- tafamidis meglumine capsule, liquid filled Vyndamax- tafamidis capsule, liquid filled". DailyMed. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Vyndaqel EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "FDA approves new treatments for heart disease caused by a serious rare disease, transthyretin mediated amyloidosis". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 September 2019. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "New Drug Therapy Approvals 2019". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d Said G, Grippon S, Kirkpatrick P (March 2012). "Tafamidis". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 11 (3): 185–186. doi:10.1038/nrd3675. PMID 22378262. S2CID 256746210.

- ^ "Assessment report: Vyndaqel tafamidis meglumine Procedure No.: EMEA/H/C/002294" (PDF). EMA. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2020. See EMA index page Archived 20 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine for updates.

- ^ Labaudiniere R (2014). "Chapter 9: Discovery and Development of Tafamidis for the Treatment of TTR Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy". In Pryde DC, Palmer MJ (eds.). Orphan Drugs and Rare Diseases. RSC Drug Discovery Series No. 38. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-806-4.

- ^ Razavi H, Palaninathan SK, Powers ET, Wiseman RL, Purkey HE, Mohamedmohaideen NN, et al. (June 2003). "Benzoxazoles as transthyretin amyloid fibril inhibitors: synthesis, evaluation, and mechanism of action". Angewandte Chemie. 42 (24): 2758–2761. doi:10.1002/anie.200351179. PMID 12820260.

- ^ a b c Jones D (November 2010). "Modifying protein misfolding". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 9 (11): 825–827. doi:10.1038/nrd3316. PMID 21030987. S2CID 30702908.

- ^ a b Borman S (25 January 2010). "Attacking Amyloids". Chemical & Engineering News. 88 (4): 30–32. doi:10.1021/cen-v088n004.p030.

- ^ Breznitz SM, O'Shea RP, Allen TJ (March 2008). "University Commercialization Strategies in the Development of Regional Bioclusters". Journal of Product Innovation Management. 25 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2008.00290.x.

- ^ Grogan K (19 June 2012). "FDA rejects Pfizer rare disease drug tafamidis". Pharma Times.

- ^ a b "Report on the Deliberation Results" (PDF). Evaluation and Licensing Division, Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Drug Trial Snapshots: Vyndaqel/Vyndamax". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Tafamidis meglumine Orphan Drug Designation and Approval". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA rejects Pfizer rare disease drug tafamidis". PharmaTimes online. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Vyndaquel & Vyndamax". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "AusPAR: Tafamidis and Tafamidis meglumine". Therapeutic Goods Administration. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Brito D, Albrecht FC, de Arenaza DP, Bart N, Better N, Carvajal-Juarez I, et al. (26 October 2023). "World Heart Federation Consensus on Transthyretin Amyloidosis Cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM)". Global Heart. 18 (1): 59. doi:10.5334/gh.1262. PMC 10607607. PMID 37901600.

- ^ "Pfizer's year in review". Pfizer 2023 Annual Report. 31 December 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams D (March 2013). "Recent advances in the treatment of familial amyloid polyneuropathy". Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 6 (2): 129–139. doi:10.1177/1756285612470192. PMC 3582309. PMID 23483184.

- Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, Waddington Cruz M, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Lozeron P, et al. (August 2012). "Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial". Neurology. 79 (8): 785–792. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661eb1. PMC 4098875. PMID 22843282.