Dissection

| Dissection | |

|---|---|

Dissection of a pregnant rat in a biology class | |

| |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004210 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Dissection (from Latin dissecare "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

Dissection has been used for centuries to explore anatomy. Objections to the use of cadavers have led to the use of alternatives including virtual dissection of computer models.

In the field of surgery, the term "dissection" or "dissecting" means more specifically the practice of separating an anatomical structure (an organ, nerve or blood vessel) from its surrounding connective tissue in order to minimize unwanted damage during a surgical procedure.

Overview

[edit]Plant and animal bodies are dissected to analyze the structure and function of its components. Dissection is practised by students in courses of biology, botany, zoology, and veterinary science, and sometimes in arts studies. In medical schools, students dissect human cadavers to learn anatomy.[1] Zoötomy is sometimes used to describe "dissection of an animal".

Human dissection

[edit]A key principle in the dissection of human cadavers (sometimes called androtomy) is the prevention of human disease to the dissector. Prevention of transmission includes the wearing of protective gear, ensuring the environment is clean, dissection technique[2] and pre-dissection tests to specimens for the presence of HIV and hepatitis viruses.[3] Specimens are dissected in morgues or anatomy labs. When provided, they are evaluated for use as a "fresh" or "prepared" specimen.[3] A "fresh" specimen may be dissected within some days, retaining the characteristics of a living specimen, for the purposes of training. A "prepared" specimen may be preserved in solutions such as formalin and pre-dissected by an experienced anatomist, sometimes with the help of a diener.[3] This preparation is sometimes called prosection.[4]

Most dissection involves the careful isolation and removal of individual organs, called the Virchow technique.[2][5] An alternative more cumbersome technique involves the removal of the entire organ body, called the Letulle technique. This technique allows a body to be sent to a funeral director without waiting for the sometimes time-consuming dissection of individual organs.[2] The Rokitansky method involves an in situ dissection of the organ block, and the technique of Ghon involves dissection of three separate blocks of organs - the thorax and cervical areas, gastrointestinal and abdominal organs, and urogenital organs.[2][5] Dissection of individual organs involves accessing the area in which the organ is situated, and systematically removing the anatomical connections of that organ to its surroundings. For example, when removing the heart, connects such as the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava are separated. If pathological connections exist, such as a fibrous pericardium, then this may be deliberately dissected along with the organ.[2]

Autopsy and necropsy

[edit]Dissection is used to help to determine the cause of death in autopsy (called necropsy in other animals) and is an intrinsic part of forensic medicine.[6]

History

[edit]

Classical antiquity

[edit]Human dissections were carried out by the Greek physicians Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Chios in the early part of the third century BC.[7][8] Before then, animal dissection had been carried out systematically starting from the fifth century BC.[9] During this period, the first exploration into full human anatomy was performed rather than a base knowledge gained from 'problem-solution' delving.[10] While there was a deep taboo in Greek culture concerning human dissection, there was at the time a strong push by the Ptolemaic government to build Alexandria into a hub of scientific study.[10] For a time, Roman law forbade dissection and autopsy of the human body,[11] so anatomists relied on the cadavers of animals or made observations of human anatomy from injuries of the living. Galen, for example, dissected the Barbary macaque and other primates, assuming their anatomy was basically the same as that of humans, and supplemented these observations with knowledge of human anatomy which he acquired while tending to wounded gladiators.[8][12][13][14]

Celsus wrote in On Medicine I Proem 23, "Herophilus and Erasistratus proceeded in by far the best way: they cut open living men - criminals they obtained out of prison from the kings and they observed, while their subjects still breathed, parts that nature had previously hidden, their position, color, shape, size, arrangement, hardness, softness, smoothness, points of contact, and finally the processes and recesses of each and whether any part is inserted into another or receives the part of another into itself."

Galen was another such writer who was familiar with the studies of Herophilus and Erasistratus.

India

[edit]

The ancient societies that were rooted in India left behind artwork on how to kill animals during a hunt.[15] The images showing how to kill most effectively depending on the game being hunted relay an intimate knowledge of both external and internal anatomy as well as the relative importance of organs.[15] The knowledge was mostly gained through hunters preparing the recently captured prey. Once the roaming lifestyle was no longer necessary it was replaced in part by the civilization that formed in the Indus Valley. Unfortunately, there is little that remains from this time to indicate whether or not dissection occurred, the civilization was lost to the Aryan people migrating.[15]

Early in the history of India (2nd to 3rd century), the Arthashastra described the 4 ways that death can occur and their symptoms: drowning, hanging, strangling, or asphyxiation.[16] According to that source, an autopsy should be performed in any case of untimely demise.[16]

The practice of dissection flourished during the 7th and 8th century. It was under their rule that medical education was standardized. This created a need to better understand human anatomy, so as to have educated surgeons. Dissection was limited by the religious taboo on cutting the human body. This changed the approach taken to accomplish the goal. The process involved the loosening of the tissues in streams of water before the outer layers were sloughed off with soft implements to reach the musculature. To perfect the technique of slicing, the prospective students used gourds and squash. These techniques of dissection gave rise to an advanced understanding of the anatomy and the enabled them to complete procedures used today, such as rhinoplasty.[15]

During medieval times the anatomical teachings from India spread throughout the known world; however, the practice of dissection was stunted by Islam.[15] The practice of dissection at a university level was not seen again until 1827, when it was performed by the student Pandit Madhusudan Gupta.[15] Through the 1900s, the university teachers had to continually push against the social taboos of dissection, until around 1850 when the universities decided that it was more cost effective to train Indian doctors than bring them in from Britain.[15] Indian medical schools were, however, training female doctors well before those in England.[15]

The current state of dissection in India is deteriorating. The number of hours spent in dissection labs during medical school has decreased substantially over the last twenty years.[15] The future of anatomy education will probably be an elegant mix of traditional methods and integrative computer learning.[15] The use of dissection in early stages of medical training has been shown more effective in the retention of the intended information than their simulated counterparts.[15] However, there is use for the computer-generated experience as review in the later stages.[15] The combination of these methods is intended to strengthen the students' understanding and confidence of anatomy, a subject that is infamously difficult to master.[15] There is a growing need for anatomist—seeing as most anatomy labs are taught by graduates hoping to complete degrees in anatomy—to continue the long tradition of anatomy education.[15]

Islamic world

[edit]

From the beginning of the Islamic faith in 610 A.D.,[17] Shari'ah law has applied to a greater or lesser extent within Muslim countries,[17] supported by Islamic scholars such as Al-Ghazali.[18] Islamic physicians such as Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) (1091–1161) in Al-Andalus,[19] Saladin's physician Ibn Jumay during the 12th century, Abd el-Latif in Egypt c. 1200,[20] and Ibn al-Nafis in Syria and Egypt in the 13th century may have practiced dissection,[18][21][22] but it remains ambiguous whether or not human dissection was practiced. Ibn al-Nafis, a physician and Muslim jurist, suggested that the "precepts of Islamic law have discouraged us from the practice of dissection, along with whatever compassion is in our temperament",[3] indicating that while there was no law against it, it was nevertheless uncommon. Islam dictates that the body be buried as soon as possible, barring religious holidays, and that there be no other means of disposal such as cremation.[17] Prior to the 10th century, dissection was not performed on human cadavers.[17] The book Al-Tasrif, written by Al-Zahrawi in 1000 A.D., details surgical procedure that differed from the previous standards.[23] The book was an educational text of medicine and surgery which included detailed illustrations.[23] It was later translated and took the place of Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine as the primary teaching tool in Europe from the 12th century to the 17th century.[23] There were some that were willing to dissect humans up to the 12th century, for the sake of learning, after which it was forbidden. This attitude remained constant until 1952, when the Islamic School of Jurisprudence in Egypt ruled that "necessity permits the forbidden".[17] This decision allowed for the investigation of questionable deaths by autopsy.[17] In 1982, the decision was made by a fatwa that if it serves justice, autopsy is worth the disadvantages.[17] Though Islam now approves of autopsy, the Islamic public still disapproves. Autopsy is prevalent in most Muslim countries for medical and judicial purposes.[17] In Egypt it holds an important place within the judicial structure, and is taught at all the country's medical universities.[17] In Saudi Arabia, whose law is completely dictated by Shari'ah, autopsy is viewed poorly by the population but can be compelled in criminal cases;[17] human dissection is sometimes found at university level.[17] Autopsy is performed for judicial purposes in Qatar and Tunisia.[17] Human dissection is present in the modern day Islamic world, but is rarely published on due to the religious and social stigma.[17]

Tibet

[edit]Tibetan medicine developed a rather sophisticated knowledge of anatomy, acquired from long-standing experience with human dissection. Tibetans had adopted the practice of sky burial because of the country's hard ground, frozen for most of the year, and the lack of wood for cremation. A sky burial begins with a ritual dissection of the deceased, and is followed by the feeding of the parts to vultures on the hill tops. Over time, Tibetan anatomical knowledge found its way into Ayurveda[24] and to a lesser extent into Chinese medicine.[25][26]

Christian Europe

[edit]

Throughout the history of Christian Europe, the dissection of human cadavers for medical education has experienced various cycles of legalization and proscription in different countries. Dissection was rare during the Middle Ages, but it was practised,[27] with evidence from at least as early as the 13th century.[28][29][30] The practice of autopsy in Medieval Western Europe is "very poorly known" as few surgical texts or conserved human dissections have survived.[31] A modern Jesuit scholar has claimed that the Christian theology contributed significantly to the revival of human dissection and autopsy by providing a new socio-religious and cultural context in which the human cadaver was no longer seen as sacrosanct.[28]

A non-existent edict[32] Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine of the 1163 Council of Tours and an early 14th-century decree of Pope Boniface VIII have mistakenly been identified as prohibiting dissection and autopsy; misunderstanding or extrapolation from these edicts may have contributed to reluctance to perform such procedures.[33][a] The Middle Ages witnessed the revival of an interest in medical studies, including human dissection and autopsy.[8][34]

Frederick II (1194–1250), the Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that any that were studying to be a physician or a surgeon must attend a human dissection, which would be held no less than every five years.[10] Some European countries began legalizing the dissection of executed criminals for educational purposes in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Mondino de Luzzi carried out the first recorded public dissection around 1315.[10] At this time, autopsies were carried out by a team consisting of a Lector, who lectured; the Sector, who did the dissection; and the Ostensor, who pointed to features of interest.[10]

The Italian Galeazzo di Santa Sofia made the first public dissection north of the Alps in Vienna in 1404.[35]

Vesalius in the 16th century carried out numerous dissections in his extensive anatomical investigations. He was attacked frequently for his disagreement with Galen's opinions on human anatomy. Vesalius was the first to lecture and dissect the cadaver simultaneously.[10][36]

The Catholic Church is known to have ordered an autopsy on conjoined twins Joana and Melchiora Ballestero in Hispaniola in 1533 to determine whether they shared a soul. They found that there were two distinct hearts, and hence two souls, based on the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles, who believed the soul resided in the heart.[37]

Human dissection was also practised by Renaissance artists. Though most chose to focus on the external surfaces of the body, some like Michelangelo Buonarotti, Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Baccio Bandinelli, and Leonardo da Vinci sought a deeper understanding. However, there were no provisions for artists to obtain cadavers, so they had to resort to unauthorised means, as indeed anatomists sometimes did, such as grave robbing, body snatching, and murder.[10]

Anatomization was sometimes ordered as a form of punishment, as, for example, in 1806 to James Halligan and Dominic Daley after their public hanging in Northampton, Massachusetts.[38]

In modern Europe, dissection is routinely practised in biological research and education, in medical schools, and to determine the cause of death in autopsy. It is generally considered a necessary part of learning and is thus accepted culturally. It sometimes attracts controversy, as when Odense Zoo decided to dissect lion cadavers in public before a "self-selected audience".[39][40]

Britain

[edit]

In Britain, dissection remained entirely prohibited from the end of the Roman conquest and through the Middle Ages to the 16th century, when a series of royal edicts gave specific groups of physicians and surgeons some limited rights to dissect cadavers. The permission was quite limited: by the mid-18th century, the Royal College of Physicians and Company of Barber-Surgeons were the only two groups permitted to carry out dissections, and had an annual quota of ten cadavers between them. As a result of pressure from anatomists, especially in the rapidly growing medical schools, the Murder Act 1752 allowed the bodies of executed murderers to be dissected for anatomical research and education. By the 19th century this supply of cadavers proved insufficient, as the public medical schools were growing, and the private medical schools lacked legal access to cadavers. A thriving black market arose in cadavers and body parts, leading to the creation of the profession of body snatching, and the infamous Burke and Hare murders in 1828, when 16 people were murdered for their cadavers, to be sold to anatomists. The resulting public outcry led to the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832, which increased the legal supply of cadavers for dissection.[41]

By the 21st century, the availability of interactive computer programs and changing public sentiment led to renewed debate on the use of cadavers in medical education. The Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry in the UK, founded in 2000, became the first modern medical school to carry out its anatomy education without dissection.[42]

United States

[edit]

In the United States, dissection of frogs became common in college biology classes from the 1920s, and were gradually introduced at earlier stages of education. By 1988, some 75 to 80 percent of American high school biology students were participating in a frog dissection, with a trend towards introduction in elementary schools. The frogs are most commonly from the genus Rana. Other popular animals for high-school dissection at the time of that survey were, among vertebrates, fetal pigs, perch, and cats; and among invertebrates, earthworms, grasshoppers, crayfish, and starfish.[43] About six million animals are dissected each year in United States high schools (2016), not counting medical training and research. Most of these are purchased already dead from slaughterhouses and farms.[44]

Dissection in U.S. high schools became prominent in 1987, when a California student, Jenifer Graham, sued to require her school to let her complete an alternative project. The court ruled that mandatory dissections were permissible, but that Graham could ask to dissect a frog that had died of natural causes rather than one that was killed for the purposes of dissection; the practical impossibility of procuring a frog that had died of natural causes in effect let Graham opt out of the required dissection. The suit gave publicity to anti-dissection advocates. Graham appeared in a 1987 Apple Computer commercial for the virtual-dissection software Operation Frog.[45][46] The state of California passed a Student's Rights Bill in 1988 requiring that objecting students be allowed to complete alternative projects.[47] Opting out of dissection increased through the 1990s.[48]

In the United States, 17 states[b] along with Washington, D.C. have enacted dissection-choice laws or policies that allow students in primary and secondary education to opt out of dissection. Other states including Arizona, Hawaii, Minnesota, Texas, and Utah have more general policies on opting out on moral, religious, or ethical grounds.[49] To overcome these concerns, J. W. Mitchell High School in New Port Richey, Florida, in 2019 became the first US high school to use synthetic frogs for dissection in its science classes, instead of preserved real frogs.[50][51][52]

As for the dissection of cadavers in undergraduate and medical school, traditional dissection is supported by professors and students, with some opposition, limiting the availability of dissection. Upper-level students who have experienced this method along with their professors agree that "Studying human anatomy with colorful charts is one thing. Using a scalpel and an actual, recently-living person is an entirely different matter."[53]

Acquisition of cadavers

[edit]The way in which cadaveric specimens are obtained differs greatly according to country.[54] In the UK, donation of a cadaver is wholly voluntary. Involuntary donation plays a role in about 20 percent of specimens in the US and almost all specimens donated in some countries such as South Africa and Zimbabwe.[54] Countries that practice involuntary donation may make available the bodies of dead criminals or unclaimed or unidentified bodies for the purposes of dissection.[54] Such practices may lead to a greater proportion of the poor, homeless and social outcasts being involuntarily donated.[54] Cadavers donated in one jurisdiction may also be used for the purposes of dissection in another, whether across states in the US,[3] or imported from other countries, such as with Libya.[54] As an example of how a cadaver is donated voluntarily, a funeral home in conjunction with a voluntary donation program identifies a body who is part of the program. After broaching the subject with relatives in a diplomatic fashion, the body is then transported to a registered facility. The body is tested for the presence of HIV and hepatitis viruses. It is then evaluated for use as a "fresh" or "prepared" specimen.[3]

Disposal of specimens

[edit]Cadaveric specimens for dissection are, in general, disposed of by cremation. The deceased may then be interred at a local cemetery. If the family wishes, the ashes of the deceased are then returned to the family.[3] Many institutes have local policies to engage, support and celebrate the donors. This may include the setting up of local monuments at the cemetery.[3]

Use in education

[edit]

Human cadavers are often used in medicine to teach anatomy or surgical instruction.[3][54] Cadavers are selected according to their anatomy and availability. They may be used as part of dissection courses involving a "fresh" specimen so as to be as realistic as possible—for example, when training surgeons.[3] Cadavers may also be pre-dissected by trained instructors. This form of dissection involves the preparation and preservation of specimens for a longer time period and is generally used for the teaching of anatomy.[3]

Alternatives

[edit]Some alternatives to dissection may present educational advantages over the use of animal cadavers, while eliminating perceived ethical issues.[55] These alternatives include computer programs, lectures, three dimensional models, films, and other forms of technology. Concern for animal welfare is often at the root of objections to animal dissection.[56] Studies show that some students reluctantly participate in animal dissection out of fear of real or perceived punishment or ostracism from their teachers and peers, and many do not speak up about their ethical objections.[57][58]

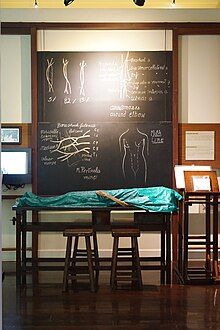

One alternative to the use of cadavers is computer technology. At Stanford Medical School, software combines X-ray, ultrasound and MRI imaging for display on a screen as large as a body on a table.[59] In a variant of this, a "virtual anatomy" approach being developed at New York University, students wear three dimensional glasses and can use a pointing device to "[swoop] through the virtual body, its sections as brightly colored as living tissue." This method is claimed to be "as dynamic as Imax [cinema]".[60]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Proponents of animal-free teaching methodologies argue that alternatives to animal dissection can benefit educators by increasing teaching efficiency and lowering instruction costs while affording teachers an enhanced potential for the customization and repeat-ability of teaching exercises. Those in favor of dissection alternatives point to studies which have shown that computer-based teaching methods "saved academic and nonacademic staff time ... were considered to be less expensive and an effective and enjoyable mode of student learning [and] ... contributed to a significant reduction in animal use" because there is no set-up or clean-up time, no obligatory safety lessons, and no monitoring of misbehavior with animal cadavers, scissors, and scalpels.[61][62][63]

With software and other non-animal methods, there is also no expensive disposal of equipment or hazardous material removal. Some programs also allow educators to customize lessons and include built-in test and quiz modules that can track student performance. Furthermore, animals (whether dead or alive) can be used only once, while non-animal resources can be used for many years—an added benefit that could result in significant cost savings for teachers, school districts, and state educational systems.[61]

Several peer-reviewed comparative studies examining information retention and performance of students who dissected animals and those who used an alternative instruction method have concluded that the educational outcomes of students who are taught basic and advanced biomedical concepts and skills using non-animal methods are equivalent or superior to those of their peers who use animal-based laboratories such as animal dissection.[64][65]

Some reports state that students' confidence, satisfaction, and ability to retrieve and communicate information was much higher for those who participated in alternative activities compared to dissection. Three separate studies at universities across the United States found that students who modeled body systems out of clay were significantly better at identifying the constituent parts of human anatomy than their classmates who performed animal dissection.[66][67][68]

Another study found that students preferred using clay modeling over animal dissection and performed just as well as their cohorts who dissected animals.[69]

In 2008, the National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT) affirmed its support for classroom animal dissection stating that they "Encourage the presence of live animals in the classroom with appropriate consideration to the age and maturity level of the students ... NABT urges teachers to be aware that alternatives to dissection have their limitations. NABT supports the use of these materials as adjuncts to the educational process but not as exclusive replacements for the use of actual organisms."[70]

The National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) "supports including live animals as part of instruction in the K-12 science classroom because observing and working with animals firsthand can spark students' interest in science as well as a general respect for life while reinforcing key concepts" of biological sciences. NSTA also supports offering dissection alternatives to students who object to the practice.[71]

The NORINA database lists over 3,000 products which may be used as alternatives or supplements to animal use in education and training.[72][non-primary source needed] These include alternatives to dissection in schools. InterNICHE has a similar database and a loans system.[73][non-primary source needed]

Additional images

[edit]-

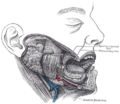

Dissection of a human cheek from Gray's Anatomy (1918)

-

Dissection of a spiny dogfish

-

Dissection of human axilla

-

Human abdomen and thorax

-

Cow brain prepared for dissection

-

Dissection in a secondary school GCSE class

-

Technique of dissection and glycerination in bovine articulation (tarsus)

See also

[edit]- 1788 Doctors' riot in New York City

- Vivisection

- Forensics

- Andreas Vesalius, founder of modern anatomy

- Jean-Joseph Sue, 18th century surgeon and anatomist

Notes

[edit]- ^ "the pope did not forbid anatomical dissections but only the dissections performed with the purpose of preserving the bodies for distant burial"[28]

- ^ California, Connecticut, D.C., Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia all have statewide laws or department of education policies that allow students to opt out.

References

[edit]- ^ McLachlan, John C.; Patten, Debra (17 February 2006). "Anatomy teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future". Medical Education. 40 (3): 243–253. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02401.x. PMID 16483327. S2CID 30909540.

- ^ a b c d e Waters, Brenda L. (2009). "2. Principles of Dissection". In Waters, Brenda L (ed.). Handbook of Autopsy Practice - Springer. pp. 11–12. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-127-7. ISBN 978-1-58829-841-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robertson, Hugh J.; Paige, John T.; Bok, Leonard (2012-07-12). Simulation in Radiology. OUP USA. pp. 15–20. ISBN 9780199764624.

- ^ "prosect - definition of prosect in English from the Oxford dictionary". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ a b Connolly, Andrew J.; Finkbeiner, Walter E.; Ursell, Philip C.; Davis, Richard L. (2015-09-23). Autopsy Pathology: A Manual and Atlas. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323287807.

- ^ "Interactive Autopsy". Australian Museum. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ von Staden, Heinrich (1992). "The discovery of the body: Human dissection and its cultural contexts in ancient Greece". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 65 (3): 223–241. PMC 2589595. PMID 1285450.

- ^ a b c Brenna, Connor T. A. (2021). "Bygone theatres of events: A history of human anatomy and dissection". The Anatomical Record. 305 (4): 2–5. doi:10.1002/ar.24764. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 34551186. S2CID 237608991.

- ^ See Bubb 2022: 12. Claire Bubb. 2022. Dissection in Classical Antiquity: A Social and Medical History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh, Sanjib Kumar (2015-09-01). "Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 48 (3): 153–169. doi:10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.153. ISSN 2093-3665. PMC 4582158. PMID 26417475.

- ^ Aufderheide, Arthur C. (2003). The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0521177351.

Tragically, the prohibition of human dissection by Rome in 150 BC arrested this progress and few of their findings survived.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian, 'The Unknown Galen', (2002), p. 89

- ^ Von Staden, Heinrich, Herophilus (1989), p. 140

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip, Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey (2007), p. 348

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jacob, Tony (2013). "History of teaching anatomy in India: from ancient to modern times". Anatomical Sciences Education. 6 (5): 351–8. doi:10.1002/ase.1359. PMID 23495119. S2CID 25807230.

- ^ a b Mathiharan, Karunakaran (September 2005). "Origin and Development of Forensic Medicine in India". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 26 (3): 254–260. doi:10.1097/01.paf.0000163839.24718.b8. PMID 16121082. S2CID 29095914.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mohammed, Madadin; Kharoshah, Magdy (2014). "Autopsy in Islam and current practice in Arab Muslim countries". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 23: 80–3. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2014.02.005. PMID 24661712.

- ^ a b Savage-Smith, Emilie (1995). "Attitudes toward dissection in medieval Islam". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 50 (1): 67–110. doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67. PMID 7876530.

- ^ Ibn Zuhr and the Progress of Surgery, http://muslimheritage.com/article/ibn-zuhr-and-progress-surgery

- ^ Emilie Savage-Smith (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, pp. 903–962 [951–952]. Routledge, London and New York.

- ^ Al-Dabbagh, S.A. (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation". The Lancet. 1 (8074): 1148. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90318-5. PMID 77431. S2CID 43154531.

- ^ Hajar A Hajar Albinali (2004). "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting". Heart Views. 5 (2): 74–85.

- ^ a b c Chavoushi, Seyed Hadi; Ghabili, Kamyar; Kazemi, Abdolhassan; Aslanabadi, Arash; Babapour, Sarah; Ahmedli, Rafail; Golzari, Samad E.J. (August 2012). "Surgery for Gynecomastia in the Islamic Golden Age: Al-Tasrif of Al-Zahrawi (936-1013 AD)". ISRN Surgery. 2012: 934965. doi:10.5402/2012/934965. PMC 3459224. PMID 23050167.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (2001). The Roots of Ayurveda. Penguin Classics.

- ^ Strober, Deborah Hart; Strober, Gerald S. (2005). His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The Oral Biography. Wiley. p. 14. ISBN 978-0471680017.

- ^ Svoboda, Robert E. (1996). Tao and Dharma: Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda. p. 89.

- ^ Classen, Albrecht (2016). Death in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: The Material and Spiritual Conditions of the Culture of Death. Walter de Gruyter. p. 388. ISBN 978-3-11-043697-6.

- ^ a b c P. Prioreschi, "Determinants of the revival of dissection of the human body in the Middle Ages", Medical Hypotheses (2001) 56(2), 229–234

- ^ "In the 13th century, the realisation that human anatomy could best be taught by dissection of the human body resulted in its legalisation of publicly dissecting criminals in some European countries between 1283 and 1365" – this was, however, still contrary to the edicts of the Church. Philip Cheung, "Public Trust in Medical Research?" (2007), page 36

- ^ "Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious". Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), page 195

- ^ Charlier, Philippe; Huynh-Charlier, Isabelle; Poupon, Joël; Lancelot, Eloïse; Campos, Paula F.; Favier, Dominique; et al. (May 2014). "A glimpse into the early origins of medieval anatomy through the oldest conserved human dissection (Western Europe, 13th c. A.D.)". Archives of Medical Science. 10 (2): 366–373. doi:10.5114/aoms.2013.33331. PMC 4042035. PMID 24904674.

- ^ Charles H. Talbot. Medicine in Medieval England. London: Oldbourne, 1967. p. 55, n. 13.

- ^ "While during this period the Church did not forbid human dissections in general, certain edicts were directed at specific practices. These included the Ecclesia Abhorret a Sanguine in 1163 by the Council of Tours and Pope Boniface VIII's command to terminate the practice of dismemberment of slain crusaders' bodies and boiling the parts to enable defleshing for return of their bones. Such proclamations were commonly misunderstood as a ban on all dissection of either living persons or cadavers (Rogers & Waldron, 1986)[clarification needed], and progress in anatomical knowledge by human dissection did not thrive in that intellectual climate." Arthur Aufderheide, The Scientific Study of Mummies (2003), p. 5

- ^ "Current scholarship reveals that Europeans had considerable knowledge of human anatomy, not just that based on Galen and his animal dissections. For the Europeans had performed significant numbers of human dissections, especially postmortem autopsies during this era", "Many of the autopsies were conducted to determine whether or not the deceased had died of natural causes (disease) or whether there had been foul play, poisoning, or physical assault. Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious". Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), p. 195

- ^ Regal, Wolfgang; Nanut, Michael (December 13, 2007). Vienna – A Doctor's Guide: 15 walking tours through Vienna's medical history. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-211-48952-9.

- ^ C. D. O'Malley, Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage, Isis 45:2, 1954

- ^ Freedman, David H. (September 2012). "20 Things you didn't know about autopsies". Discovery. 9: 72.

- ^ Brown, Richard D. (June 2011). "'Tried, Convicted, and Condemned, in Almost Every Bar-room and Barber's Shop': Anti-Irish Prejudice in the Trial of Dominic Daley and James Halligan, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1806". The New England Quarterly. 84 (2): 205–233. doi:10.1162/tneq_a_00087. S2CID 57560527.

- ^ "Odense Zoo animal dissections: EAZA response". European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ "Animals used for scientific purposes". European Union. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Cheung, pp. 37–44

- ^ Cheung, pp. 33, 35

- ^ Orlans, F. Barbara; Beauchamp, Tom L.; Dresser, Rebecca; Morton, David B.; Gluck, John P. (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. pp. 213. ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4.

- ^ "Dissection". American Anti-Vivisection Society. 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Howard Rosenberg: Apple Computer's 'Frog' Ad Is Taken Off the Air. Los Angeles Times, November 10, 1987.

- ^ F. Barbara Orlans; Tom L. Beauchamp; Rebecca Dresser; David B. Morton; John P. Gluck (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4.

- ^ Orlans et al., pp. 209–211

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (May 29, 1997). "Frogs' Best Friends: Students Who Won't Dissect Them". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Your Right Not to Dissect". PETA2.

- ^ Aaro, David (November 30, 2019). "Florida high school first in world to use synthetic frogs for dissection". Fox News. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Elassar, Alaa (November 30, 2019). "A Florida high school is the first in the world to provide synthetic frogs for students to dissect". CNN. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Lewis, Sophie (November 26, 2019). "Florida high school introduces synthetic frogs for science class dissection". CBS News. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Jenner, Andrew (2012). "EMU News". EMU's Cadaver Dissection Gives Pre-Med Students Big Advantage. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Gangata, Hope; Ntaba, Phatheka; Akol, Princess; Louw, Graham (2010-08-01). "The reliance on unclaimed cadavers for anatomical teaching by medical schools in Africa". Anatomical Sciences Education. 3 (4): 174–183. doi:10.1002/ase.157. ISSN 1935-9780. PMID 20544835. S2CID 22596215.

- ^ Balcombe, Jonathan (2001). "Dissection: The Scientific Case for Alternatives". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 4 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1207/S15327604JAWS0402_3. S2CID 143465900. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Stainsstreet, M; Spofforth, N; Williams, T (1993). "Attitudes of undergraduate students to the uses of animals". Studies in Higher Education. 18 (2): 177–196. doi:10.1080/03075079312331382359.

- ^ Oakley, J (2012). "Dissection and choice in the science classroom: student experiences, teacher responses, and a critical analysis of the right to refuse". Journal of Teaching and Learning. 8 (2). doi:10.22329/jtl.v8i2.3349.

- ^ Oakley, J (2013). ""I didn't feel right about animal dissection": Dissection objectors share their science class experiences". Society & Animals. 21 (1): 360–378. doi:10.1163/15685306-12341267.

- ^ White, Tracie (2011). "Body image: Computerized table lets students do virtual dissection". Stanford Medicine: News Center. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Singer, Natasha (7 January 2012). "The Virtual Anatomy, Ready for Dissection". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b Dewhurt, D; Jenkinson, L (1995). "The impact of computer-based alternatives on the use of animals in undergraduate teaching: A pilot study". ATLA. 23 (4): 521–530.

- ^ Predavec, M. (2001). "Evaluation of E-Rat, a computer-based rat dissection, in terms of student learning outcomes". Journal of Biological Education. 35 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1080/00219266.2000.9655746. S2CID 85201408.

- ^ Youngblut, C. (2001). "Use of multimedia technology to provide solutions to existing curriculum problems: Virtual frog dissection". Doctoral Dissertation. Bibcode:2001PhDT........42Y.

- ^ Patronek, G. J.; Rauch, A (2007). "Systematic review of comparative studies examining alternatives to the harmful use of animals in biomedical education". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 230 (1): 37–43. doi:10.2460/javma.230.1.37. PMID 17199490. S2CID 5164145.

- ^ Knight, A. (2007). "The effectiveness of humane teaching methods in veterinary education". ALTEX. 24 (2): 91–109. doi:10.14573/altex.2007.2.91. PMID 17728975.

- ^ Waters, J. R.; Van Meter, P.; Perrotti, W; Drogo, S; Cyr, R. J. (2005). "Cat dissection vs. sculpting human structures in clay: An analysis of two approaches to undergraduate human anatomy laboratory education". Advances in Physiology Education. 29 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1152/advan.00033.2004. PMID 15718380. S2CID 28694409.

- ^ Motoike, H. K.; O'Kane, R. L.; Lenchner, E.; Haspel, C. (2009). "Clay modeling as a method to learn human muscles: A community college study". Anatomical Sciences Education. 2 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1002/ase.61. PMID 19189347. S2CID 28441790.

- ^ Waters, J. R.; Van Meter, P.; Perrotti, W.; Drogo, S.; Cyr, R. J. (2011). "Human clay models versus cat dissection: How the similarity between the classroom and the exam affects student performance". Advances in Physiology Education. 35 (2): 227–236. doi:10.1152/advan.00030.2009. PMID 21652509.

- ^ DeHoff, M. E.; Clark, K. L; Meganathan, K. (2011). "Learning outcomes and student perceived value of clay modeling and cat dissection in undergraduate human anatomy and physiology". Advances in Physiology Education. 35 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1152/advan.00094.2010. PMID 21386004. S2CID 19112983.

- ^ "The Use of Animals in Biology Education". Position Statements: National Association of Biology Teachers. National Association of Biology Teachers. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "NSTA Position Statement: Responsible Use of Live Animals and Dissection in the Science Classroom". National Science Teachers Association. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ NORINA

- ^ InterNICHE

Further reading

[edit]- C. Celsus, On Medicine, I, Proem 23, 1935, translated by W. G. Spencer (Loeb Classics Library, 1992).

- Claire Bubb. 2022. Dissection in Classical Antiquity: A Social and Medical History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

[edit]- How to dissect a frog

- Dissection Alternatives

- Human Dissections

- Virtual Frog Dissection

- Alternatives To Animal Dissection in School Science Classes

- Research Project on Death and Dead Bodies, last conference: "Death and Dissection" July 2009, Berlin, Germany

- Evolutionary Biology Digital Dissection Collections Dissection photographs for study and teaching from the University at Buffalo

- The Free Dictionary