User:SunKing2/History of the Ottawa River

History

[edit]As it does to this day, the river played a vital role in life of the Algonquin people, who lived throughout its watershed at contact. The river is called Kichisìpi, meaning "Great River" in Anicinàbemowin, the Algonquin language. The Algonquin define themselves in terms of their position on the river, referring to themselves as the Omàmiwinini, 'down-river people'. Although a majority of the Algonquin First Nation lives in Quebec, the entire Ottawa Valley is Algonquin traditional territory. Present settlement is a result of adaptations made as a result of settler pressures.[1]

Some early European explorers, possibly considering the Ottawa River to be more significant than the Upper St. Lawrence River, applied the name River Canada to the Ottawa River and the St. Lawrence River below the confluence at Montreal. As the extent of the Great Lakes became clear and the river began to be regarded as a tributary, it was variously known as the Grand River, "Great River" or Grand River of the Algonquins before the present name was settled upon. This name change resulted from the Ottawa peoples' control of the river circa 1685. However, only one band of Ottawa, the Kinouncherpirini or Keinouch, ever inhabited the Ottawa Valley.

In 1615, Samuel de Champlain and Étienne Brûlé, assisted by Algonquin guides, were the first Europeans to travel up the Ottawa River and follow the water route west along the Mattawa and French Rivers to the Great Lakes. See Canadian Canoe Routes (early). For the following two centuries, this route was used by French fur traders, Voyageurs and Coureur des bois to Canada's interior. The river posed serious hazards to these travelers. The section near Deux Rivières used to have spectacular and wild rapids, namely the Rapide de la Veillée, the Trou, the Rapide des Deux Rivières, and the Rapide de la Roche Capitaine. In 1800, explorer Daniel Harmon reported 14 crosses marking the deaths of voyageurs who had drowned in the dangerous waters along this section of the Ottawa.[2]

In the early 19th century, the Ottawa River and its tributaries were used to gain access to large virgin forests of white pine. A booming trade in timber developed, and large rafts of logs were floated down the river. A scattering of small subsistence farming communities developed along the shores of the river to provide manpower for the lumber camps in winter. In 1832, following the War of 1812, the Ottawa River gained strategic importance when the Carillon Canal was completed. Together with the Rideau Canal, the Carillon Canal was constructed to provide an alternate military supply route to Kingston and Lake Ontario, bypassing the route along the Saint Lawrence River.[3]

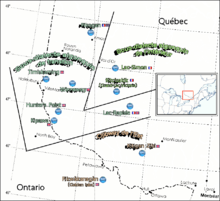

The entire Ottawa Valley is Algonquin traditional territory and, like most populated areas of Canada, is presently under Land Claim.[4]

As a relatively recent adaptation resulting from the economic pressures of the encroachment of non-native settling of the valley, the Algonquin First Nation is unevenly distributed within their territory. A majority of Algonquins reside on the Quebec side of the border, where all but two Algonquin communities are located.[1] However, there are many Algonquin communities and individuals not recognized as such by the Government of Canada under the Indian Act. These individuals are referred to as 'Non-Status Indians'. Ardoch Algonquin First Nation is one such community located in the Ottawa Valley fighting for the return of their land.

After the arrival of European settlers in North America, the first major industry of the Ottawa Valley was fur trading. The valley was part of the major cross-country route for French-Canadian Voyageurs, who would paddle canoes up the Ottawa River as far as Mattawa and then portage west through various rivers and lakes to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron. Later, lumber became the valley's major industry, and it is still important in the far western part where the valley is narrow and little farmland is available. Today, the vast majority of the valley's residents live at its eastern end in Ottawa and its suburbs, where government and technology are major industries.

In the areas of Morrison’s Island and the Allumette Island there were many archaeological sites found from the earlier years of the Algonquin First Nations tribes. Many of these sites were found by the late Clyde C. Kennedy, who was a student of history; he was very interested in history and worked hard while researching the sites. The items found on the different sites are dated from about five thousand years ago to about two thousand years ago, and are a range of different things from native copper, to spear heads.

Major cities in the Upper Ottawa Valley

[edit]Petawawa is a city located in Renfrew County, in the Ottawa Valley. It was thought to have been first settled by the Agolkin Natives and the name comes from their language meaning "where one hears the noise of the water". Samuel de Champlain visited this town and it was used as an important location for the Hudson's Bay Company. Many of the first settlers were of Irish, Scottish, and later German origin. In 1865 the township of Petawawa was incorporated because of its rich natural resources and it's important military role. It wasn't until Canada Day 1997 that it was recognized as the Town of Petawawa. Today it is the home of one of the largest Canadian Forces Land Force Command bases in Canada CFB Petawawa.

Pembroke is located in Renfrew County on the Ottawa River. It is known as “the heart of the Ottawa Valley”. It was established in 1858 by pioneers and became a centre for the logging industry. Today, it is the largest regional service centre between Ottawa and North Bay. It is a nice little community with many activities such as Farmer’s Markets, Santa Claus Parade, Pembroke Waterfront Festival, and much more.[5]

Historical notes

[edit]Samuel de Champlain spent the years between 1613 and 1615 traveling the Ottawa River with Algonquin and Huron guides. He was the first documented European to see the Ottawa Valley. When Champlain first arrived there the Huron, Algonquin, Iroquois, and Outaouais tribes were living in the Valley. In charting the new land Champlain inaugurated the route that would be used by French fur traders for the next 200 years.*Between 1847 and 1879 a "horse railway" was used to portage passengers from the Ottawa River steamboat in a horse-drawn car for 5.5 kilometres along the wooded shore, around the Chats Falls, on the Quebec side of the river between the ghost villages of Pontiac Village and Union Village, near Quyon Quebec, to another steamboat to continue their journey upriver.

This water route, with few portages, connected Lake Huron and the Saint Lawrence River by a much shorter route than through the lower Great Lakes. It was the mainline of the French-Canadian voyageurs engaged in the fur trade; they took canoes on the waterways along this route from Montreal to the upper Great Lakes and the pays d'en haut—the "upper country" in the old Northwest.[6]

[7] The valley of the Ottawa and Montreal Rivers and Lake Timiskaming was also part of a branch route to James Bay in the days of the fur brigades.[8] The valleys are now used by more modern forms of transportation, including the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Trans-Canada Highway.[9]

After the arrival of European settlers in North America, the Mattawa River was an important transportation corridor for native peoples of the region and formed part of the water route leading west to Lake Superior in the days of the fur trade. Canoes travelling north up the Ottawa turned left to enter the Mattawa, reaching Lake Nipissing by way of "La Vase Portage", an 11 km (7 mi) stretch of water and portages. In the 19th century, the river provided access to large untouched stands of white pine. The river was also used to transport logs to sawmills. While logging is still an important industry in this region, almost the full length of the river has been designated as a Canadian Heritage River, and as such, its shores are now protected from further development and logging. Today, the river and lakes are mainly used for recreation.

Chaudiere Falls and Rideau Falls history removed from History of Ottawa

[edit]Brûlé and Champlain were traveling west to the Great Lakes, but it would be nearly two centuries before the Europeans showed much interest in the land of present day Ottawa. However Brûlé encountered the Chaudière Falls, and the future site of what would be the City of Ottawa. The Chaudière Falls would serve as power for the lumber industry which stimulated the early growth of settlement in the area. Champlain himself originated the name, chaudière, (which the English for a time would call 'Big Kettle')[10] as he describes in his journal on June 14, 1613:

"At one place the water falls with such violence upon a rock, that, in the course of time, there has been hollowed out in it a wide and deep basin, so that the water flows round and round there and makes, in the middle, great whirlpools. Hence, the savages call it Asticou, [qui veut dire chaudiere.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)[11] This waterfall makes such a noise that it can be heard for more than two leagues off."[12]

The area includes Chaudière Island and Victoria Island to the east of that, and according to archaeological evidence, had been used by First Nations people for centuries as a centre of convergence for trade and spiritual and cultural exchange.[13] Later the nearby Parliament of Canada would speak of Ottawa as "a meeting place of three rivers, perched on a rocky point overlooking fast-moving water, wooded land and urban landscapes, within sight of sacred meeting grounds that the Algonquin peoples have always called Asinabka, or "Place of Glare Rock." (Report to Canadians, 2008, House of Commons)[14]

Champlain had also encountered the Rideau Falls, the Rideau River's most northerly point where it empties into the Ottawa River. Much of the early settlement took place between the falls, located east of Parliament Hill, and the Chaudière Falls, in the west, in what would first become Bytown, and later the city of Ottawa. The falls were named by the early French for their resemblance to a curtain (or rideau in French). The Rideau River was later named after the falls. The Rideau Canal would later bypass these falls and provide transportation to immigrants and goods. Champlain wrote:

"There is an island in the centre, all covered with trees, like the rest of the land on both sides, and the water slips down with such impetuosity that it makes an arch of four hundred paces; the Indians passing underneath it without getting wet, except for the spray produced by the fall."[10]

The early explorers, hoping to profit from the fur trade, had accomplished what Jacques Cartier was unable to do, where he was blocked near Hochelaga's Lachine Rapids, near present day Montreal. From 1613 to 1663, a royal charter from the King of France gave the successive groups monopolies to invest in New France territories and control of the fur trade and colonization. Among the first of commercial enterprises to evolve in the Ottawa Valley was the fur trade industry, largely influenced by the Hudson's Bay Company.[15] It was formed in 1670 and used the Ottawa River and its tributaries as the local conveyance for the delivery of fur products to Europe through Montreal and Quebec City.[15]

Fur Trade

[edit]all from ISBN 1-55041-554-9: Riendeau 2000.

Seeking bevear revived interest in North American in seeking sources. Over time deeper ino the interior, it initiated settlement on the shores of the St. L. River and prompted the French government ot regulate trade through controlling the intense competition through monopolies to private companies. (It is also partly responsible for N. France's slow development.)[16]

Excellent quality beaver pelts brought ot Europe fetched a high price at a time when European supplies of beaver were limited. By the end of the sixteenth century, Tadoussac was thriving in the beaver trade. Henry IV was willing to participate in the granting of royal charter of monopoly to designated regions in order to assert French sovereignty overseas, and at a low cost to France.[16]

Entymology of Ottawa as the name of the city

[edit](Brault, p19:) There were those in the town hoping that it would become the capital, and several names were suggested by several townspeople. The Bytown Gazette on March 7, 1844 first suggested using an aboriginal name, and "for the first time appears the name Ottawa". In 1853, Municipal Council, with Mayor Turgeon "proposed to rename the city to take advantage of a concidence which would give the chang in name historic significance". 1854 marked the 200th anniversary of "the opening of navigation by the Ottawa Indians on the river" "After the extermination of the Hurons by the Iroquois and the pursuit of their allies, the river became deserted for approximately 5 years. In 1654, after a truce had been signed by the Iroquois in Montreal, the Ottawas who whad taken refuge from the Manitoulin Island to Wisconsin for fear of the Iroquois, came down to trade at Montreal for the first time by way of the Algonquin River, which was afterwards known as River of the Ottawas". The name was adopted in 1854 "in a petition to the governor, the act came into effect January 1, 1855".

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Algonquin Land Claim with Ontario". Ontario Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ Ontario Heritage Foundation, Ministry of Culture and Communications

- ^ "Carillon Canal National Historic Site of Canada, Cultural Heritage". Parks Canada. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ "Algonquin Land Claim Map". Ontario Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ http://www.pembrokeontario.com/content/visiting_here/heritage_murals/

- ^ "Natural Areas Report: Mattawa River". National Heritage Information Center. Ontario Ministry of National Resources. 2005-06-05. Retrieved 2007-12-15. [dead link]

- ^ Morse, Eric (1979). Fur Trade Routes of Canada. Minoqua, WI: NorthWord Press. pp. 48–61. ISBN 1-5597-1045-4. (pages 48-61)

- ^ Morse, Eric (1979). Fur Trade Routes of Canada. Minoqua, WI: NorthWord Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 1-5597-1045-4. (pages 67-69)

- ^ "Geological Highway map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2007-12-15.. Lake Nissiping area, showing C.P.R., Highway 17, and other routes.

- ^ a b Haig 1975, pp. 42.

- ^ Champlain 1870, pp. 301.

- ^ Woods, 6.

- ^ "The Vision For Asinabka". Ottawa.ca. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ^ "Report to Canadians 2008" (PDF). House of Commons. fiscal year 2006-2007. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Dodwell 1929, pp. 5.

- ^ a b Riendeau 2000, pp. 30.

- Bibliography

- Bond, Courtney C. J. (1984), Where Rivers Meet: An Illustrated History of Ottawa, Windsor Publications, ISBN 0897811119

- Brault, Lucien (1946), Ottawa Old and New, Ottawa historical information Institute, OCLC 2947504

- Greening, W. E. (1961), The Ottawa, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, OCLC 25441343

- Haig, Robert (1975), Ottawa: City of the Big Ears, Ottawa: Haig and Haig Publishing Co., OCLC 9184321

- Knowles, Valerie (2005), Capital Lives, Ottawa: Book Coach Press, ISBN 0973907118

- Lee, David (2006), Lumber kings & shantymen : logging and lumbering in the Ottawa Valley, James Lorimer & Company, ISBN 9781550289220

- Legget, Robert (1986), Rideau Waterway, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0802065910

- Martin, Carol (1997), Ottawa: a colourguide, Formac Publishing Company, ISBN 9780887803963

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1982), Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville, Ont: Mika Publishing Company, ISBN 0919303609

- Taylor, John H. (1986), Ottawa: An Illustrated History, J. Lorimer, ISBN 9780888629814

- Woods, Shirley E. Jr. (1980), Ottawa: The Capital of Canada, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0385147228

- Van de Wetering, Marion (1997), An Ottawa Album: Glimpses of the Way We Were, ISBN 0888821956