User:Omarseid2011/List of Most Massive Stars

This is a list of the most massive stars so far discovered, in solar masses (M☉).

Uncertainties and caveats

[edit]Most of the masses listed below are contested and, being the subject of current research, remain under review and subject to revision. Indeed, many of the masses listed in the table below are inferred from theory, using difficult measurements of the stars’ temperatures and absolute brightnesses. All the masses listed below are uncertain: both the theory and the measurements are pushing the limits of current knowledge and technology. Either measurement or theory, or both, could be incorrect. For example, VV Cephei could be between 25–40 M☉, or 100 M☉, depending on which property of the star is examined.

Massive stars are rare; astronomers must look very far from the Earth to find one. All the listed stars are many thousands of light years away and that alone makes measurements difficult.

In addition to being far away, many stars of such extreme mass are surrounded by clouds of outflowing gas created by powerful stellar winds; the surrounding gas interferes with the already difficult-to-obtain measurements of stellar temperatures and brightnesses and greatly complicates the issue of estimating internal chemical compositions.[a]

Both the obscuring clouds and the great distances make it difficult to judge whether the star is just a single supermassive object or, instead, a multiple star system. A number of the "stars" listed below may actually be two or more companions orbiting too closely to distinguish, each star being massive in itself but not necessarily “supermassive”. Other combinations are possible – for example a supermassive star with one or more smaller companions or more than one giant star – but without being able to see inside the surrounding cloud, it is difficult to know the truth of the matter. More globally, statistics on stellar populations seem to indicate that the upper mass limit is in the 100–200 solar mass range.[citation needed]

Rare reliable estimates

[edit]Eclipsing binary stars are the only stars whose masses are estimated with some confidence. However note that almost all of the masses listed in the table below were inferred by indirect methods; only a few of the masses in the table were determined using eclipsing systems.

Amongst the most reliable listed masses are those for the eclipsing binaries NGC 3603-A1, WR 21a, and WR 20a. Masses for all three were obtained from orbital measurements.[b] This involves measuring their radial velocities and also their light curves. The radial velocities only yield minimum values for the masses, depending on inclination, but light curves of eclipsing binaries provide the missing information: inclination of the orbit to our line of sight.

Relevance of stellar evolution

[edit]Some stars may once have been heavier than they are today. It is likely that many have suffered significant mass loss, perhaps as much as several tens of solar masses, expelled by the process of superwind, where high velocity winds are driven by the hot photosphere into interstellar space. This process is similar to superwinds generated by asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars in form red giants or planetary nebulae. The process forms an enlarged extended envelope around the star that interacts with the nearby interstellar medium and infusing the region with elements heavier than Hydrogen or Helium.

There are also – or rather were – stars that might have appeared on the list but no longer exist as stars, or are supernova impostors; today we see only the debris.[c] The masses of the precursor stars that fueled these cataclysms can be estimated from the type of explosion and the energy released, but those masses are not listed here (see § Black holes below).

Mass limits

[edit]There are two related theoretical limits on how massive a star can possibly be: the accretion limit and the Eddington mass limit. The accretion limit is related to star formation: After about 120 M☉ have accreted in a protostar, the combined mass should have become hot enough for its heat to drive away any further incoming matter. In effect, the protostar reaches a point where it evaporates away material as fast as it collects new material. The Eddington limit is based on light pressure from the core of an already-formed star: As mass increases past ~150 M☉, the intensity of light radiated from a Population I star's core will become sufficient for the light-pressure pushing outward to exceed the gravitational force pulling inward, and the surface material of the star will be free to float away into space.

Accretion limits

[edit]Astronomers have long hypothesized that as a protostar grows to a size beyond 120 M☉, something drastic must happen. Although the limit can be stretched for very early Population III stars, and although the exact value is uncertain, if any stars still exist above 150–200 M☉ they would challenge current theories of stellar evolution.

Studying the Arches Cluster, which is currently the densest known cluster of stars in our galaxy, astronomers have confirmed that stars in that cluster do not occur any larger than about 150 M☉.

Rare ultramassive stars that exceed this limit – for example in the R136 star cluster – might be explained by the following proposal: Some of the pairs of massive stars in close orbit in young, unstable multiple-star systems must occasionally collide and merge where certain unusual circumstances hold that make a collision possible.[1]

Eddington mass limit

[edit]A limit on stellar mass arises because of light-pressure: For a sufficiently massive star the outward pressure of radiant energy generated by nuclear fusion in the star's core exceeds the inward pull of its own gravity. This effect is called the Eddington limit.

Stars of greater mass have a higher rate of core energy generation, and heavier stars' luminosities increase far out of proportion to the increase in their masses. The Eddington limit is the point beyond which a star ought to push itself apart, or at least shed enough mass to reduce its internal energy generation to a lower, maintainable rate. The actual limit-point mass depends on how opaque the gas in the star is, and metal-rich Population I stars have lower mass limits than metal-poor Population II stars, with the hypothetical metal-free Population III stars having the highest allowed mass, somewhere around 300 M☉.

In theory, a more massive star could not hold itself together because of the mass loss resulting from the outflow of stellar material. In practice the theoretical Eddington Limit must be modified for high luminosity stars and the empirical Humphreys–Davidson limit is used instead.[2]

List of the most massive stars

[edit]The following two lists show a few of the known stars with an estimated mass of 25 M☉ or greater, including the stars of Arches Cluster, Cygnus OB2 cluster, Pismis 24 cluster, and R136 cluster.

The first list gives stars that are estimated to be 80 M☉ or larger. The majority of stars thought to be more than 100 M☉ are shown, but the list is incomplete.

The second list gives examples of stars 25–79 M☉, but is far from a complete list. Note that all O-type stars have masses greater than 15 M☉ and catalogs of such stars (GOSS, Reed) list hundreds of cases.

In each list, the method used to determine the mass is included to give an idea of uncertainty: Binary stars being more securely determined than indirect methods such as conversion from luminosity, extrapolation from stellar atmosphere models, ... . The masses listed below are the stars’ current (evolved) mass, not their initial (formation) mass.

| Wolf–Rayet star |

| Luminous blue variable star |

| O-class star |

| B-class star |

| Hypergiant |

| Star name | Mass (M☉, Sun = 1) |

Distance from Earth (ly) | Method used to estimate mass | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R136a1 | 315 | 163,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| R136c | 230 | 163,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| BAT99-98 | 226 | 165,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [4] |

| R136a2 | 195 | 163,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| Melnick 42 | 189 | 163,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [5] |

| R136a3 | 180 | 163,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| HD 15558 A | >152 ± 51 | 24,400 | Binary | [6][7] |

| VFTS 682 | 150 | 164,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [8] |

| R136a6 | 150 | 157,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| Melnick 34 A | 147 | 163,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [9] |

| LH 10-3209 A | 140 | 160,000[10] | [11] in the Bean Nebula (N11B) of the Large Magellenic Cloud galaxy | |

| Melnick 34 B | 136 | 163,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [9] |

| NGC 3603-B | 132 ± 13 | 24,700 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [12] |

| HD 269810 | 130 | 163,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [13] |

| P871 | 130 | ? | [11] | |

| WR 42e | 130 ± 5 | 25,000 | Ejection in triple system | [14][d] |

| R136a4 | 124 | 157,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| Arches-F9 | 121 ± 10 | 25,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [15] |

| NGC 3603-A1a | 120 | 24,700 | Eclipsing binary | [12] |

| LSS 4067 | 120 | 9,500–12,700 | Evolutionary model | [16] |

| NGC 3603-C | 113 ± 10 | 22,500 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [12] |

| Cygnus OB2-12 | 110 | 5,220 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [17] |

| WR 25 | 110 | 10,500 | Binary? | |

| HD 93129 A | 110 | 7,500 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | |

| WR21a A | 103.6 | 26,100 | Binary | [18] |

| BAT99-33 (R99) | 103 | 16,400 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [4] |

| Arches-F1 | 110 ± 9 | 25,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [15] |

| Arches-F6 | 106 ± 5 | 25,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [15] |

| R136a5 | 101 | 157,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

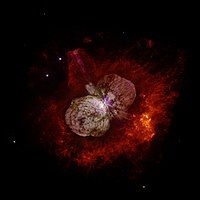

| η Carinae A | 100 | 7,500 | Luminosity/Binary | [19] The most massive star that has a Bayer designation |

| Peony Star (WR 102ka) | 100 | 26,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model? | [20] |

| Cygnus OB2 #516 | 100 | 4,700 | Luminosity? | |

| Sk -68°137 | 99 | ? | [11] | |

| R136a8 | 96 | 157,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| Arches-F7 | 96 ± 6 | 25,000 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [15] |

| HST-42 | 95 | ? | [11] | |

| P1311 | 94 | ? | [11] | |

| Sk -66°172 | 94 | ? | [11] | |

| R136b | 93 | 163,000 | Evolutionary model | [3] |

| NGC 3603-A1b | 92 | 24,800 | Eclipsing binary | [12] |

| HST-A3 | 91 | ? | [11] | |

| HD 38282 B | >90 | Luminosity | [21] | |

| Cygnus OB2 #771 | 90 | 4,700 | Luminosity/atmosphere model? | |

| HSH95 31 | 87 | Evolutionary model[3] | ||

| HD 93250 | 86.83 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [22] | |

| Arches-F15 | 88.5 ± 8.5 | Luminosity/atmosphere model | [15] | |

| LH 10-3061 | 85 | 160,000[10] | [11] in the Bean Nebula (N11B) of the Large Magellenic Cloud galaxy | |

| BI 253 | 84 | |||

| WR20a A | 82.7 ± 5.5 | Eclipsing binary | [23] | |

| MACHO 05:34-69:31 | 82 | ? | [11] | |

| WR20a B | 81.9 ± 5.5 | Eclipsing binary | [23] | |

| NGC 346-3 | 81 | ? | [11] | |

| HD 38282 A | >80 | Luminosity | [21] | |

| Sk -71 51 | 80 | Luminosity | [24] | |

| Cygnus OB2-8B | 80 | Luminosity? | ||

| WR 148 | 80 | ? | [25] | |

| HD 97950 | 80 | ? |

A few examples of mass less than 80 M☉.

Black holes

[edit]Black holes are the end point evolution of massive stars. Technically they are not stars, as they no longer generate heat and light via nuclear fusion in their cores.[f]

- Stellar black holes are objects with approximately 4–15 M☉.

- Intermediate-mass black holes range from 100–10 000 M☉.

- Supermassive black holes are in the range of millions or billions M☉.

See also

[edit]- Hypergiant

- List of brightest stars

- List of brown dwarfs

- List of galaxies

- List of hottest stars

- List of largest cosmic structures

- List of largest nebulae

- List of largest stars

- List of most luminous stars

- List of most massive black holes

- List of most massive neutron stars

- Lists of stars

- Luminous blue variable

- Supergiant star

- Wolf–Rayet star

Notes

[edit]- ^ For some methods, different determinations of chemical composition lead to different estimates of mass.

- ^ For a binary star, it is possible to measure the individual masses of the two stars by studying their orbital motions, using Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

- ^ For examples of stellar debris see hypernovae and supernova remnant.

- ^ This unusual measurement was made by assuming the star was ejected from a three-body encounter in NGC 3603. This assumption also means that the current star is the result of a merger between two original close binary components. The mass is consistent with evolutionary mass for a star with the observed parameters.

- ^ The masses were revised with better data, but refinements are still needed.

- ^ Note that some black holes may have cosmological origins, and would then never have been stars. This is thought to be especially likely in the cases of the most massive black holes.

References

[edit]- ^ Ulmer, A.; Fitzpatrick, E. L. (1998). "Revisiting the modified Eddington limit for massive stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 504 (1): 200–206. arXiv:astro-ph/9708264. Bibcode:1998ApJ...504..200U. doi:10.1086/306048.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Crowther, Paul A.; Caballero-Nieves, S. M.; Bostroem, K. A.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Schneider, F. R. N.; Walborn, N. R.; Angus, C. R.; Brott, I.; Bonanos, A.; de Koter, A.; de Mink, S. E.; Evans, C. J.; Gräfener, G.; Herrero, A.; Howarth, I. D.; Langer, N.; Lennon, D. J.; Puls, J.; Sana, H.; Vink, J. S. (2016). "The R136 star cluster dissected with Hubble Space Telescope/STIS. I. Far-ultraviolet spectroscopic census and the origin of He II λ1640 in young star clusters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 458 (1): 624–659. arXiv:1603.04994. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.458..624C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Hainich, R.; Rühling, U.; Todt, H.; Oskinova, L. M.; Liermann, A.; Gräfener, G.; Foellmi, C.; Schnurr, O.; Hamann, W. -R. (2014). "The Wolf–Rayet stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 565: A27. arXiv:1401.5474. Bibcode:2014A&A...565A..27H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322696.

- ^ Bestenlehner, J. M.; Gräfener, G.; Vink, J. S.; Najarro, F.; de Koter, A.; Sana, H.; Evans, C. J.; Crowther, P. A.; Hénault-Brunet, V.; Herrero, A.; Langer, N.; Schneider, F. R. N.; Simón-Díaz, S.; Taylor, W. D.; Walborn, N. R. (2014). "The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey. XVII. Physical and wind properties of massive stars at the top of the main sequence". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 570. A38. arXiv:1407.1837. Bibcode:2014A&A...570A..38B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423643.

- ^ a b De Becker, M.; Rauw, G.; Manfroid, J.; Eenens, P. (2006). "Early-type stars in the young open cluster IC 1805". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 456 (3): 1121–1130. arXiv:astro-ph/0606379. Bibcode:2006A&A...456.1121D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065300.

- ^ a b Garmany, C. D.; Massey, P. (1981). "HD 15558 - an extremely luminous O-type binary star". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 93: 500. Bibcode:1981PASP...93..500G. doi:10.1086/130866.

- ^ Bestenlehner, J. M.; Vink, J. S.; Gräfener, G.; Najarro, F.; Evans, C. J.; Bastian, N.; Bonanos, A. Z.; Bressert, E.; Crowther, P. A.; Doran, E.; Friedrich, K.; Hénault-Brunet, V.; Herrero, A.; De Koter, A.; Langer, N.; Lennon, D. J.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Sana, H.; Soszynski, I.; Taylor, W. D. (2011). "The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 530: L14. arXiv:1105.1775. Bibcode:2011A&A...530L..14B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117043.

- ^ a b Tehrani, Katie A.; Crowther, Paul A.; Bestenlehner, Joachim M.; Littlefair, Stuart P.; Pollock, A M T.; Parker, Richard J.; Schnurr, Olivier (2019). "Weighing Melnick 34: The most massive binary system known". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 484 (2): 2692–2710. arXiv:1901.04769. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.484.2692T. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "A Cauldron of Newborn Stars". Sky and Telescope. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Walborn, Nolan R.; Howarth, Ian D.; Lennon, Daniel J.; Massey, Philip; Oey, M. S.; Moffat, Anthony F. J.; Skalkowski, Gwen; Morrell, Nidia I.; Drissen, Laurent; Parker, Joel Wm. (2002). "A New Spectral Classification System for the Earliest O Stars: Definition of Type O2" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 123 (5): 2754–2771. Bibcode:2002AJ....123.2754W. doi:10.1086/339831.

- ^ a b c d Crowther, P. A.; Schnurr, O.; Hirschi, R.; Yusof, N.; Parker, R. J.; Goodwin, S. P.; Kassim, H. A. (2010). "The R136 star cluster hosts several stars whose individual masses greatly exceed the accepted 150 M⊙ stellar mass limit". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 408 (2): 731–751. arXiv:1007.3284. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408..731C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17167.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Evans, C. J.; Walborn, N. R.; Crowther, P. A.; Hénault-Brunet, V.; Massa, D.; Taylor, W. D.; Howarth, I. D.; Sana, H.; Lennon, D. J.; Van Loon, J. T. (2010). "A Massive Runaway Star from 30 Doradus". The Astrophysical Journal. 715 (2): L74. arXiv:1004.5402. Bibcode:2010ApJ...715L..74E. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/715/2/L74.

- ^ Gvaramadze; Kniazev; Chene; Schnurr (2012). "Two massive stars possibly ejected from NGC 3603 via a three-body encounter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 430: L20–L24. arXiv:1211.5926. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.430L..20G. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sls041.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e Gräfener, G.; Vink, J. S.; De Koter, A.; Langer, N. (2011). "The Eddington factor as the key to understand the winds of the most massive stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 535: A56. arXiv:1106.5361. Bibcode:2011A&A...535A..56G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116701.

- ^ Massey, P.; Degioia-Eastwood, K.; Waterhouse, E. (2001). "The Progenitor Masses of Wolf-Rayet Stars and Luminous Blue Variables Determined from Cluster Turnoffs. II. Results from 12 Galactic Clusters and OB Associations". The Astronomical Journal. 121 (2): 1050–1070. arXiv:astro-ph/0010654. Bibcode:2001AJ....121.1050M. doi:10.1086/318769.

- ^ Clark, J. S.; Najarro, F.; Negueruela, I.; Ritchie, B. W.; Urbaneja, M. A.; Howarth, I. D. (2012). "On the nature of the galactic early-B hypergiants". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 541: A145. arXiv:1202.3991. Bibcode:2012A&A...541A.145C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117472.

- ^ a b Shenar, T.; Hainich, R.; Todt, H.; Sander, A.; Hamann, W.-R.; Moffat, A. F. J.; Eldridge, J. J.; Pablo, H.; Oskinova, L. M.; Richardson, N. D. (2016). "Wolf-Rayet stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud: II. Analysis of the binaries". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 1604. A22. arXiv:1604.01022. Bibcode:2016A&A...591A..22S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527916.

- ^ Clementel, N.; Madura, T. I.; Kruip, C. J. H.; Paardekooper, J.-P.; Gull, T. R. (2015). "3D radiative transfer simulations of Eta Carinae's inner colliding winds - I. Ionization structure of helium at apastron". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 447 (3): 2445–2458. arXiv:1412.7569. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.447.2445C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Barniske, A.; Oskinova, L. M.; Hamann, W. -R. (2008). "Two extremely luminous WN stars in the Galactic center with circumstellar emission from dust and gas". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 486 (3): 971–984. arXiv:0807.2476. Bibcode:2008A&A...486..971B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809568.

- ^ a b Sana, H.; Van Boeckel, T.; Tramper, F.; Ellerbroek, L. E.; De Koter, A.; Kaper, L.; Moffat, A. F. J.; Schnurr, O.; Schneider, F. R. N.; Gies, D. R. (2013). "R144 revealed as a double-lined spectroscopic binary". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 432: L26–L30. arXiv:1304.4591. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.432L..26S. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt029.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Repolust, T.; Puls, J.; Herrero, A. (2004). "Stellar and wind parameters of Galactic O-stars. The influence of line-blocking/blanketing". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 415 (1): 349–376. Bibcode:2004A&A...415..349R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034594.

- ^ a b Rauw, G.; Crowther, P. A.; De Becker, M.; Gosset, E.; Nazé, Y.; Sana, H.; Van Der Hucht, K. A.; Vreux, J. -M.; Williams, P. M. (2005). "The spectrum of the very massive binary system WR?20a (WN6ha + WN6ha): Fundamental parameters and wind interactions" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 432 (3): 985–998. Bibcode:2005A&A...432..985R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042136.

- ^ Meynadier, F.; Heydari-Malayeri, M.; Walborn, N. R. (2005). "The LMC H II region N 214C and its peculiar nebular blob". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 436 (1): 117–126. arXiv:astro-ph/0511439. Bibcode:2005A&A...436..117M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042543.

- ^ a b Matteucci, Francesca; Giovannelli, Franco (2000). "The Evolution of the Milky Way". The Evolution of the Milky Way: Stars Versus Clusters. Edited by Francesca Matteucci and Franco Giovannelli. Published by Kluwer Academic Publishers. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. 255. Bibcode:2000ASSL..255.....M. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0938-6. ISBN 978-94-010-3799-0.

- ^ Taylor, W. D.; Evans, C. J.; Sana, H.; Walborn, N. R.; De Mink, S. E.; Stroud, V. E.; Alvarez-Candal, A.; Barbá, R. H.; Bestenlehner, J. M.; Bonanos, A. Z.; Brott, I.; Crowther, P. A.; De Koter, A.; Friedrich, K.; Gräfener, G.; Hénault-Brunet, V.; Herrero, A.; Kaper, L.; Langer, N.; Lennon, D. J.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Markova, N.; Morrell, N.; Monaco, L.; Vink, J. S. (2011). "The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 530: L10. arXiv:1103.5387. Bibcode:2011A&A...530L..10T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116785.

- ^ Fang, M.; Van Boekel, R.; King, R. R.; Henning, T.; Bouwman, J.; Doi, Y.; Okamoto, Y. K.; Roccatagliata, V.; Sicilia-Aguilar, A. (2012). "Star formation and disk properties in Pismis 24". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 539: A119. arXiv:1201.0833. Bibcode:2012A&A...539A.119F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015914.

- ^ a b c d Herrero, A.; Puls, J.; Najarro, F. (2002). "Fundamental parameters of Galactic luminous OB stars VI. Temperatures, masses and WLR of Cyg OB2 supergiants". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 396 (3): 949–966. arXiv:astro-ph/0210469. Bibcode:2002A&A...396..949H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021432.

- ^ Orosz, J. A.; McClintock, J. E.; Narayan, R.; Bailyn, C. D.; Hartman, J. D.; Macri, L.; Liu, J.; Pietsch, W.; Remillard, R. A.; Shporer, A.; Mazeh, T. (2007). "A 15.65-solar-mass black hole in an eclipsing binary in the nearby spiral galaxy M 33". Nature. 449 (7164): 872–875. arXiv:0710.3165. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..872O. doi:10.1038/nature06218. PMID 17943124.

- ^ Adriane Liermann et all (2011). "High-mass stars in the Galactic center Quintuplet cluster". Bulletin de la Societe Royale des Sciences de Liege. 80: 160–164. Bibcode:2011BSRSL..80..160L.

- ^ a b Bhatt, H.; Pandey, J. C.; Kumar, B.; Singh, K. P.; Sagar, R. (2010). "X-ray emission characteristics of two Wolf–Rayet binaries: V444 Cyg and CD Cru". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 402 (3): 1767–1779. arXiv:0911.1489. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.402.1767B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15999.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Bouret, J. -C.; Hillier, D. J.; Lanz, T.; Fullerton, A. W. (2012). "Properties of Galactic early-type O-supergiants: A combined FUV-UV and optical analysis". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 544: A67. arXiv:1205.3075. Bibcode:2012A&A...544A..67B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118594.

- ^ Shenar, T. (2016). "The Tarantula Massive Binary Monitoring project: II. A first SB2 orbital and spectroscopic analysis for the Wolf-Rayet binary R145". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 1610: A85. arXiv:1610.07614. Bibcode:2017A&A...598A..85S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629621.

- ^ Vink, J. S.; Davies, B.; Harries, T. J.; Oudmaijer, R. D.; Walborn, N. R. (2009). "On the presence and absence of disks around O-type stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 505 (2): 743–753. arXiv:0909.0888. Bibcode:2009A&A...505..743V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912610.

- ^ a b Williams, S. J.; et al. (2008). "Dynamical Masses for the Large Magellanic Cloud Massive Binary System [L72] LH 54-425". The Astrophysical Journal. 682 (1): 492–498. arXiv:0802.4232. Bibcode:2008ApJ...682..492W. doi:10.1086/589687.

- ^ Geballe, T. R.; Najarro, F.; Rigaut, F.; Roy, J. ‐R. (2006). "TheK‐Band Spectrum of the Hot Star in IRS 8: An Outsider in the Galactic Center?". The Astrophysical Journal. 652 (1): 370–375. arXiv:astro-ph/0607550. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..370G. doi:10.1086/507764.

- ^ Gorlova, N.; Lobel, A.; Burgasser, A. J.; Rieke, G. H.; Ilyin, I.; Stauffer, J. R. (2006). "On the CO Near‐Infrared Band and the Line‐splitting Phenomenon in the Yellow Hypergiant ρ Cassiopeiae". The Astrophysical Journal. 651 (2): 1130–1150. arXiv:astro-ph/0607158. Bibcode:2006ApJ...651.1130G. doi:10.1086/507590.

- ^ Paul A Crowther; Carpano; Hadfield; Pollock (2007). "On the optical counterpart of NGC300 X-1 and the global Wolf–Rayet content of NGC300". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 469 (31): L31. arXiv:0705.1544. Bibcode:2007A&A...469L..31C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077677.

- ^ Bulik, T.; Belczynski, K.; Prestwich, A. (2011). "Ic10 X-1/ngc300 X-1: The Very Immediate Progenitors of Bh-Bh Binaries". The Astrophysical Journal. 730 (2): 140. arXiv:0803.3516. Bibcode:2011ApJ...730..140B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/730/2/140.

- ^ Kashi, A.; Soker, N. (2010). "Periastron Passage Triggering of the 19th Century Eruptions of Eta Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal. 723 (1): 602–611. arXiv:0912.1439. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..602K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/602.

- ^ Raul E. Puebla; D. John Hillier; Janos Zsargó; David H. Cohen; Maurice A. Leutenegger (2015). "X-ray, UV and optical analysis of supergiants: ε Ori". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 456 (3): 2907–2936. arXiv:1511.09365. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456.2907P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2783.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ferguson, Brian A.; Ueta, Toshiya (March 2010). "Differential Proper-motion Study of the Circumstellar Dust Shell of the Enigmatic Object, HD 179821". The Astrophysical Journal. 711 (2): 613–618. arXiv:1001.3135. Bibcode:2010ApJ...711..613F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/711/2/613.

- ^ "VLT image of the surroundings of VY Canis Majoris seen with SPHERE". www.eso.org. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Wittkowski, M.; Hauschildt, P.H.; Arroyo-Torres, B.; Marcaide, J.M. (5 April 2012). "Fundamental properties and atmospheric structure of the red supergiant VY CMa based on VLTI/AMBER spectro-interferometry". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 540: L12. arXiv:1203.5194. Bibcode:2012A&A...540L..12W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219126.

- ^ Almeida, L. A.; Sana, H.; de Mink, S. E.; et al. (13 October 2015). "DISCOVERY OF THE MASSIVE OVERCONTACT BINARY VFTS 352: EVIDENCE FOR ENHANCED INTERNAL MIXING". The Astrophysical Journal. 812 (2): 102. arXiv:1509.08940. Bibcode:2015ApJ...812..102A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/812/2/102.

- ^ Wittkowski, M.; Arroyo-Torres, B.; Marcaide, J. M.; Abellan, F. J.; Chiavassa, A.; Guirado, J. C. (2017). "VLTI/AMBER spectro-interferometry of the late-type supergiants V766 Cen (=HR 5171 A), σ Oph, BM Sco, and HD 206859". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 597: A9. arXiv:1610.01927. Bibcode:2017A&A...597A...9W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629349.

- ^ Achmad, L.; Lamers, H. J. G. L. M.; Pasquini, L. (1997). "Radiation driven wind models for A, F and G supergiants". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 320: 196. Bibcode:1997A&A...320..196A.

- ^ Moscadelli, L.; Goddi, C. (2014). "A multiple system of high-mass YSOs surrounded by disks in NGC 7538 IRS1". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 566: A150. arXiv:1404.3957. Bibcode:2014A&A...566A.150M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423420.

- ^ Ohnaka, K.; Driebe, T.; Hofmann, K. H.; Weigelt, G.; Wittkowski, M. (2009). "Resolving the dusty torus and the mystery surrounding LMC red supergiant WOH G64". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 4: 454. Bibcode:2009IAUS..256..454O. doi:10.1017/S1743921308028858.

External links

[edit]- Statistics in Arches cluster

- Most Massive Star Discovered

- Arches cluster

- How Heavy Can a Star Get?

- LBV 1806–20

Category:Lists of stars Stars, most massive Category:Lists of astronomical objects Massive stars