User:O11badger/sandbox

Helping: Brickman’s four models and factors that influence when we help. PSY2203, word count: 2000

[edit]Background

[edit]

When we help is affected by who we believe is responsible for the problem and who we believe is responsible for the solution; Brickman et al (1982) proposed four models of when we help (Philip et al., 1982). Helping is defined as a situation where people provide assistance in solving an issue of another person (Stukas & Clary, 2012). It is a type of prosocial behaviour which is defined as a voluntary behaviour that is done to help someone else (Ramkissoon, 2021). Different studies have been conducted that explain who is most likely to help and why or how we help others. In the past, certain events such as the murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964 brought up questions about when we help (Jarrett, 2017). This led to the theory of the bystander effect which suggests people are less likely to help if others are around due to expecting the other people to help (Latane & Darley, 1968). The bystander effect has been covered a lot in other articles, however other factors that affect when we help such as time pressure, cost and similarity of the person needing help have not. Therefore we will talk about when we help which includes Brickman et al’s (1982) four models and these other factors. We will also talk about how helping behaviour is measured as this seems to be missed out in other articles.

When do we help?

[edit]The models

[edit]We are more likely to help someone when we believe the situation they are in isn’t their fault. If the situation is external then we show sympathy and help but if the situation is internal and controllable by the person then we are likely to show little sympathy and not help (Weiner, 1986). Brickman et al (1982) proposed four models that describe when we help someone in need and bridges the gap between clinical and social psychology (Philip et al., 1982).

The moral model believes that people are responsible for creating their problem and that they are also responsible for finding a solution to it (Philip et al., 1982). An example of people that often fall into this are people that drink alcohol and they are seen as putting in a lack of effort, no matter how much effort they are putting in (Philip et al., 1982). A study found that medical and moral models have led to stigmatizing attitudes towards people with alcohol use disorders (Jansen, 2020). This may lead to a vicious cycle as little help is offered due to these attitudes. This suggests that the moral model is outdated and should be changed so help is given to this category of people. Helping behaviours that may take place in this model are usually reminding people that they are responsible for finding a solution (Philip et al., 1982).

The compensatory model believes people are not responsible for their problems but they are still responsible for their solutions (Philip et al., 1982). The responsibility of using help given by people lies with the person suffering (Philip et al., 1982). The kind of help that is given to people deemed to be in this model is resources or opportunities that the person may not have due to the environment they are in (Philip et al., 1982). Political leaders are often seen as in this model and this can make them see the world in a negative way (Philip et al., 1982).

The medical model believes that people are not responsible for causing their problems and are also not responsible for the solutions (Philip et al., 1982). This model follows our healthcare system (Philip et al., 1982). This is a good model as people under this model aren’t seen as weak or expected to find a solution (Philip et al., 1982). It could be argued that people struggling with alcoholism as described under the moral model should be seen under this model, as often becoming an alcoholic is out of a person’s control and is due to the environment someone is in.

The final model is the enlightenment model that says that people are responsible for creating their problems but are not responsible for creating a solution (Philip et al., 1982). An example of this is alcoholics anonymous where it is required for people to realise that God and a good community is needed to overcome their drinking problem, and that they cannot overcome it by themselves. There are other factors that influence when we help which we will discuss now.

Factors that influence when we help

[edit]There are different factors that influence whether we are likely to help. Research has been conducted that shows that perceived similarity influences altruistic giving (Schütt, 2023). It was found that participants in a similar condition gave more to their partner compared to the participants in the dissimilar condition (Schütt, 2023). A strength of the study was that participants were controlled for the empathy personality trait to make sure that prosocial behaviours weren’t different between groups due to participants being more helpful to begin with (Schütt, 2023). Another study recruited Manchester United football fans and asked them to write what it meant to be a Manchester united fan which primes their identity (Levine et al., 2005). They then walked to the next task and came across someone who needed their help who was either in a Manchester United shirt, Liverpool shirt or neutral clothing (Levine et al., 2005). The participant was more likely to help a Manchester united fan than a Liverpool fan or a neutral person (Levine et al., 2005). This could be explained by the social categorisation theory (Tajfel, 1979) as you are more likely to help someone in your ingroup as you perceive them to be similar to yourself.

Another factor that affects whether we help is whether it costs us to help. A study was conducted on 73 four year olds where they had to complete one of 3 novel tasks alongside a puppet that was controlled by the experimenter (Green et al., 2018). The puppet was never able to complete the task due to missing pieces and once the puppet realised this it acted as either upset or not (Green et al., 2018). Whether a cost was incurred was manipulated and it was found that children helped more in the no cost conditions compared to the cost conditions (Green et al., 2018). This suggests that we are more likely to help when there is no cost to us.

Another situational factor that influences when we help is the level of ambiguity of the situation. It was found that there was a greater level of helping behaviours when up to groups of 2 participants were exposed to a non ambiguous situation compared to when they were exposed to an ambiguous situation (Clark & Word, 1974). As the situation is ambiguous, people won’t have interpreted the situation as an emergency so they won’t feel the need to help. These factors can help explain the murder of Kitty Genovese.

Kitty Genovese

[edit]Kitty Genovese was stabbed to death in 1964 whilst walking home from work at night and it was thought that 38 people witnessed the event but did nothing (Jarrett, 2017). This event caused research into the bystander effect (Latane & Darley, 1968). It can also be argued that factors such as perceived similarity influenced whether people were likely to help (Schütt, 2023). Kitty Genovese was a woman and worked in a bar. In the 1960s women had limited rights and were seen as inferior, and her job perhaps made her seem lower class. This meant that bystanders, particularly the men, would be less likely to help as they don’t see the similarity between themselves and the person in need.

Another factor that may have influenced whether we help is the cost of helping (Green et al., 2018). The cost of helping would have been very high as there would have been a risk of death or serious injury if someone had helped. This would have reduced helping behaviour.

Although Kitty Genovese’s murder influenced research into the bystander effect, it can be argued that there were other factors that may have influenced the lack of helping taking place just as much as this. Although the bystander effect is an important phenomenon, researchers missed a great opportunity to look at the impact of situational factors on Kitty Genovese’s murder.

How is helping measured?

[edit]There is a gap in articles explaining how helping is measured. To measure a variable, first it has to be operationalised. Helping can be operationalised by observing prosocial behaviour.

One way that helping is measured is through scales (Caprara et al., 2005; Carlo & Randall, 2002). The prosociality scale is a self-report measure with 16 items that look at adult prosocialness, an example question asked is “I am pleased to help my friends/ colleagues in their activities” and participants rated each response on a Likert scale (Caprara et al., 2005). A limitation of this scale is that participants are likely to show social desirability bias in order to be liked by people as helping people is the socially acceptable thing to do. Another scale used is the Prosocial Tendencies measure which is a 23 item self-report measure which is split up into six different subscales (Carlo & Randall, 2002). This is a strength as the researchers realised that prosocial behaviour isn’t one behaviour and that it contains different elements which were decided using factor analysis (Carlo & Randall, 2002). A meta-analysis was conducted on this scale and it was found that although mostly similar, certain gender-typed behaviours had larger gender differences than other prosocial behaviours (Xiao et al., 2019). This means that it is important to consider which prosocial behaviours are more typical of certain genders when creating a scale, otherwise the measure may have an unintended bias towards a particular gender due to the behaviours measured.

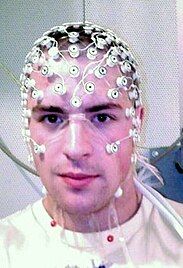

Another way that the tendency to help has been measured is by using brain scanning techniques. A study used an EEG to measure the electrical activity in the brain alongside a survey asking about particular helping behaviours given to friends or strangers (Saulin et al., 2018). It was found that the baseline activation in the right dorsolateral PFC predicted how likely someone was to help a friend and that the baseline activation of the dorsomedial PFC predicted the likelihood of helping a stranger; these brain areas are associated with strategic social behaviour and social cognition respectively (Saulin et al., 2018). This study tells us about particular brain areas that influence whether an individual will help or not. Further studies should use brain scanning methods and self-report measures together, although the expense element of brain scanning might prevent this being used in lots of studies.

A final method that has been used is observational studies. An example used in a study is accidentally dropping a pen and seeing if someone shouted to let the experimenter know or picked it up to give it back (R. V. Levine et al., 2001). A limitation of observational methods are that you won’t be able to tell the reason behind someone helping.

Conclusion

[edit]In conclusion, this article has looked at Brickman et al’s (1982) four models of helping and we have discussed the influence that being categorised into certain models could have on the victim and how this may lead to a lack of help. We have discussed factors that influence when we help such as perceived similarity, the cost of helping and the ambiguity of the situation and we have linked it to the murder of Kitty Genovese which sparked psychological research into helping. Methods that are used to measure helping include self-report scales, brain scans such as EEG and observational methods. All these methods have their limitations such as cost and social desirability bias. Future research should focus on updating Brickman’s four models as they are outdated and cause stigmatising attitudes, especially the moral model, and look at the impact of situational factors on the murder of Kitty Genovese.

References

[edit]Philip, B., Carulli, R. V., Jurgis, K., Dan, C., Ellen, C., & Louise, K. (1982). Models of helping and coping. American Psychologist, 37(4), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.37.4.368

Stukas, A., & Clary, E. (2012). Altruism and helping behavior. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 100–107). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-375000-6.00019-7

Ramkissoon, H. (2021). Prosociality in times of separation and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.008

Jarrett, C. (2017). More than 50 years on, the murder of Kitty Genovese is still throwing up fresh psychological revelations. BPS. https://www.bps.org.uk/research-digest/more-50-years-murder-kitty-genovese-still-throwing-fresh-psychological-revelations

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10(3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026570

Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springler-Verlag.

Jansen, T. L. (2020). Models of Perception: Lay Theories and Stigma towards Alcohol Use Disorder. STARS. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/807/

Schütt, C. A. (2023). The effect of perceived similarity and social proximity on the formation of prosocial preferences. Journal of Economic Psychology, 99, 102678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2023.102678

Levine, M., Prosser, A., Evans, D., & Reicher, S. (2005). Identity and Emergency Intervention: How social group membership and inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(4), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271651

Tajfel, H. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations/Brooks/Cole.

Green, M., Kirby, J. N., & Nielsen, M. (2018). The cost of helping: An exploration of compassionate responding in children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 36(4), 673–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12252

Clark, R. D., & Word, L. E. (1974). Where is the apathetic bystander? Situational characteristics of the emergency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036000

Caprara, G. V., Steca, P., Zelli, A., & Capanna, C. (2005). A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.21.2.77

Carlo, G., & Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014033032440

Xiao, S. X., Hashi, E. C., Korous, K. M., & Eisenberg, N. (2019). Gender differences across multiple types of prosocial behavior in adolescence: A meta‐analysis of the prosocial tendency measure‐revised (PTM‐R). Journal of Adolescence, 77(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.003

Saulin, A., Baumgartner, T., Gianotti, L. R. R., Hofmann, W., & Knoch, D. (2018). Frequency of helping friends and helping strangers is explained by different neural signatures. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 19(1), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-00655-2

Levine, R. V., Norenzayan, A., & Philbrick, K. (2001). Cross-Cultural differences in helping strangers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 543–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032005002