User:Amirani1746/sandbox5

| Amirani1746/sandbox5 Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian, ~

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration of A. parvidens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Aristonectinae |

| Genus: | †Aristonectes Cabrera, 1941 |

| Type species | |

| Aristonectes parvidens Cabrera, 1941

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Aristonectes (meaning "best swimmer") is an extinct genus of large elasmosaurid plesiosaurs that lived during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous. Two species are known, A. parvidens and A. quiriquinensis, whose fossil remains were discovered in what are now Patagonia and Antarctica. Throughout the 20th century, Aristonectes was a difficult animal for scientists to analyze due to poor fossil preparation, its relationships to other genera were uncertain. After subsequent revisions and discoveries carried out from the beginning of the 21st century, Aristonectes is now recognised as the type genus of the subfamily Aristonectinae, a lineage of elasmosaurids characterized by an enlarged skull and a reduced length of the neck.

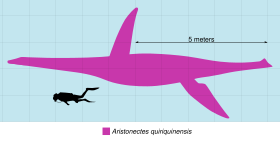

Measuring more than 10 m (33 ft) long, Aristonectes is a notably imposing plesiosaur. A referred specimen discovered in Antarctica has an estimated size of more than 11 m (36 ft) long, which would make this genus one of the largest known plesiosaurs. The paddle-like limbs of Aristonectes are unusually large for an elasmosaurid, reaching almost 3 m (9.8 ft) in length, suggesting a total wingspan of around 7 m (23 ft) for the animal. The skull is ogival-shaped and is flattened, possessing sharp forward-facing teeth. According to estimates, 13 teeth would have been present in each premaxilla, 50 teeth in the maxilla and 50 to 63 or more teeth in the lower jaw.

According to its morphology, mainly cranial, Aristonectes fed by mixing prey and sediment in the benthic zones, like the modern gray whale. As in other plesiosaurs, gastroliths (stomach stones) would have been used by Aristonectes either to help digest its food or to aid in buoyancy, although there is little support for the first hypothesis. According to its geographical distribution in the fossil record, Aristonectes would have regularly migrated between Patagonia and Antarctica.

Research history

[edit]A. parvidens

[edit]The first Aristonectes fossil was discovered long before the genus was named by Ángel Cabrera in 1941.[1] In 1848, the Franco-Chilean naturalist Claude Gay described the first known plesiosaur from South America, Plesiosaurus chilensis, on the basis of a single caudal vertebra discovered in Quiriquina Island, in Concepción Province, Chile.[2] In a book published in 1889, Richard Lydekker placed this species in the genus Cimoliosaurus.[3] In 1895, Wilhelm Deecke moved it into the pliosaurid genus Pliosaurus as Pliosaurus chilensis, and referred other fossils that have been discovered in the same locality to this species. Among these fossils are some vertebrae, a femur, fragments of an ischium, and ribs.[4] In 1918, the Russian paleontologist Pavel Pravoslavlev moved it into the related genus Elasmosaurus, as Elasmosaurus chilensis.[5] In 1941, Cabrera described a different specimen from Chubut Province, Argentina as the new genus and species Aristonectes parvidens. In the same publication, he listed Elasmosaurus chilensis as "Plesiosaurus" chilensis, expressing uncertainty regarding its affinities.[6] In 1949, Edwin H. Colbert found that the holotype specimen of "P." chilensis (the caudal vertebra originally described by Gay) belongs to a pliosauroid, but also was uncertain about its generic placement. Also in the article, he considers that the other fossil material previously attributed to "P." chilensis could come from elasmosaurids.[7][8] In an analysis published in 2013 by José P. O'Gorman and colleagues, the holotype specimen of "P." chilensis was recognized as potentially belonging to A. parvidens. As this specimen merely consists of a single caudal vertebra, it was referred to as A. cf. parvidens to indicate uncertainty in its assignment.[1]

The first specimen formally identified as A. parvidens was collected by Cristian S. Petersen in collaboration with local resident Victor Saldivia, in the Cañadón de los Loros, near the municipality of Paso del Sapo in Chubut Province, Argentina.[6] The specimen was discovered in the Lefipán Formation and was dated to the Maastrichtian.[9][10][11] In September 1940, Pablo Groeber sent this specimen to the Museo de La Plata as a donation for the Dirección de Minas y Geología del Ministerio de Agricultura (Directorate of Mines and Geology of the Ministry of Agriculture). A vertebra and incomplete phalanges from the same region had previously been donated to the Museo de La Plata by Mario Reguiló, and were subsequently referred to the holotype, since catalogued as MLP 40-XI-14-6, as they most likely came from the same specimen.[6] The holotype consists of a partial skull attached to the mandible, the atlas and axis, 21 cervical vertebrae (including 16 anterior cervicals which are articulated), 8 caudal vertebrae and an incomplete left forelimb. The specimen was interpreted as an adult, or even an elderly individual.[9][12] Cabrera described the animal as Aristonectes parvidens in his article published in 1941 by the museum that houses the fossil material.[6] The genus name Aristonectes comes from the Ancient Greek words ἄριστος (áristos, "best", "superior") and νηκτός (nêktós, "swimmer"), and may be translated as "best swimmer", so named to indicate the best preserved specimen of plesiosaur from Argentina known at that time. The specific epithet parvidens means "small teeth", in reference to the rather small size of the tooth sockets.[13] Since the unknown parts of the original specimen were heavily reconstructed, the precise anatomy of Aristonectes remained uncertain throughout the 20th century.[14][15][16] In 2003, Spanish paleontologist Zulma Gasparini and colleagues re-prepared the holotype skull along with the atlas and axis, in an attempt to clarify its anatomy.[9] In 2016, the same author revised the holotype again.[11]

A. quiriquinensis

[edit]The first discovery of the second known species, A. quiriquinensis, dates back to the late 1950s, when Argentinian paleontologist Rodolfo Casamiquela discovered a partial skeleton in Las Tablas Bay, located north of Quiriquina Island, Chile. The specimen, cataloged as SGO.PV.260, was found in Maastrichtian beds of the Quiriquina Formation; initially, five vertebrae, a humerus fragment, and the distal end of a limb were visible. The hardness of the rocks containing the fossils made subsequent preparation difficult. The preparation uncovered additional body parts, with the specimen including all four limbs, a posterior portion of the neck, most of the trunk, and a complete tail. It is interpreted as a juvenile. This specimen was first analyzed in 2012 and identified as an indeterminate aristonectine,[17] before being assigned to the genus Aristonectes in 2013.[18]

In 2001, Chilean paleontologist Mario E. Suárez collected a partial skull, mandibular fragments and 12 anterior cervical vertebrae from a beach near Cocholgüe, located north of Tomé. This material was described in the following year and attributed to Aristonectes, but identification as a separate species was then impossible due to lack of preparation.[19] In early 2009, a second excavation was carried out independently at the same site by a team from the University of Concepción of Chile and the University of Heidelberg of Germany. This excavation recovered 119 blocks of sandstone, most of them with bone material, but some were degraded by the periodic immersion of sea water that caused brittle surfaces on the most delicate parts. Additionally, several anatomical contacts were lost as blocks of sandstone were cut from the beach using a rock saw at low tide. The precise location of the find and the taphonomic distribution of the fossils show that they belong to the same specimen that was discovered in 2001. The bones were sent to the Chilean National Museum of Natural History for the preparation and scientific analysis. The completely prepared fossil consists of the skull, the axis and the atlas, 12 anterior cervical vertebrae, 23 middle to posterior cervical vertebrae, most of the trunk, the two almost complete forelimbs and a significant part of the right hind limb. The specimen was likely a young adult, and is cataloged as SGO.PV.957. In 2014, Rodrigo Otero and colleagues made it the holotype of the new species A. quiriquinensis; these researchers also referred the earlier specimen, SGO.PV.260, to this species. The specific epithet is a reference to the formation of Quiriquina, which is the type locality of this taxon.[12]

In 2015, two other specimens from Quiriquina Island were referred to A. quiriquinensis. These are composed of a complete left femur and a proximal part of a humerus, cataloged respectively as SGO.PV.135 and SGO.PV.169, which were previously referred to the now dubious genus Mauisaurus.[20] In 2018, the holotype specimen was redescribed after further preparation. In the same publication, another specimen, SGO.PV.94, consisting of a series of anterior caudal vertebrae, was also referred to A. quiriquinensis.[21]

Description

[edit]

Aristonectes is a plesiosaur that had been particularly difficult for scientists to analyze because of its incompleteness.[15][16] Its relationships remained unclear until more recent research carried out on A. parvidens and the discovery of the second species A. quiriquinensis have made it possible to redescribe its anatomy and classify it among the elasmosaurids.[9][11][12][21][14] However, anatomical comparisons between A. parvidens and A. quiriquinensis are still limited to elements that are known from both species.[12][11] Aristonectes is a large representative of the plesiosauroids, the holotype of A. quiriquinensis having an estimated size of about or more than 10 metres (33 ft) long.[21] A referred specimen of Aristonectes discovered in the López de Bertodano Formation in Antarctica, cataloged as MLP 89-III-3-1, is considered to be one of the largest and heaviest plesiosaurs identified to date, having an estimated size between 11–11.9 metres (36–39 ft) long and a body mass of 10.7–13.5 metric tons (11.8–14.9 short tons).[22][a]

Skull

[edit]In the two known species, the skull of Aristonectes is flattened and ogive-shaped.[9][11][12][21] The size of the skull varies very slightly between the two species, that of the holotype of A. quiriquinensis having a proposed size between 65–70 cm (26–28 in), while from the holotype of A. parvidens measures 73.5 cm (28.9 in).[12] In A. quiriquinensis the squamosal bones extend well posterior to the occipital condyle. The pterygoid bones are large and project posterior to the neurocranium. The posterior extensions of the pterygoid bones are surrounding the axis and the atlas, which reduces the space between the skull and the vertebrae, and would therefore limit lateral movement at their joints.[21] Around 13 teeth were present in the premaxilla and 50 in the maxilla.[12][11] Among the unique characters of the skull of A. quiriquinensis is the presence of a mental boss (a ridge along the mandibular symphysis), a feature not observed in the holotype of A. parvidens.[12] The mandibular symphysis of Aristonectes is short.[6][9][11][12][21] The dentary bones, although being partially preserved in both species, would have an estimated total of 50 teeth in A. quiriquinensis and 63 or more in A. parvidens.[9][12][24][11][b] The mandibular symphysis of the dentary bones in A. quiriquinensis is comparatively thicker and lacks the deep groove seen in ventral view in A. parvidens. The most posterior teeth of A. parvidens were about 60 mm (2.4 in) rostrally from the coronoid process. In A. quiriquinensis, there are no tooth sockets present, although 130 mm (5.1 in) of the mandible is preserved rostral to the coronoid process. Therefore, it is likely that A. quiriquinensis would have fewer teeth than A. parvidens. In A. parvidens, the labial contact between the angular bone and the surangular, anterior to the glenoid fossa, bears a deep cavity which is not present in A. quiriquinensis.[12]

The teeth of A. quiriquinensis have an oval cross-section, being very similar to elasmosaurids of the Northern Hemisphere and the Weddellian Province (a geographical area that appeared after the isolation of Antarctica), as in Kaiwhekea. The root of complete teeth is slightly longer than the crown. The dentition of A. quiriquinensis, and most likely A. parvidens,[11][c] is homodont, which means that the teeth are all of similar shape. The largest known tooth is very thin and pointed, with ridges on the lingual side of the crown. The smaller tooth is a short-rooted replacement tooth with a similar morphology as the larger one.[12] All teeth are inclined toward the front and would not fit together when the jaws are closed.[21]

Postcranial skeleton

[edit]Although postcranial remains are known in both species, they are more completely known, and thus better documented, in A. quiriquinensis.[12][21] In 2018, Otero and his colleagues estimated that A. quiriquinensis would have had a total of 109 vertebrae, including 43 cervical, 3 pectoral, 24 dorsal, 3 sacral, and 35 caudal vertebrae.[21] The anterior cervical ribs are recurved in A. parvidens and fused distally,[6] while those of A. quiriquinensis are short and lack contacts.[12] The cervical ribs and cervical neural spines of Aristonectes are curved towards the head, similar to other members of the subfamily Aristonectinae.[12][21] This morphology would have allowed for maintaining the trunk higher than the head.[21] The neural spines present on the middle of the cervical part look like blades and are enlarged distally.[12]

The dorsal vertebrae are larger and taller than the cervical vertebrae and are also taller than they are wide. The centra of the dorsal vertebrae have amphicelous articular surfaces.[12] Between the glenoid cavities, the pectoral girdle of A. quiriquinensis is nearly one meter in width. The ribs appear thickened on their distal ends. The gastralia are pachyostotic and moderate in length. The caudal vertebrae of A. quiriquinensis are wider than tall or long. The neural spines of the caudals become progressively blunt and short and have a thick dorsal apex with a flat surface which suggests the probable existence of a strong ligament along the dorsal part of the tail.[21]

The limbs of A. quiriquinensis are very long for an elasmosaurid, the best-preserved swim paddle being about 3 m (9.8 ft) long. Combined with the aforementioned width of the pectoral girdle, this indicates a total wingspan of 7 m (23 ft). In aquatic tetrapods, such limb proportions are only observable in the rhomaleosaurid Meyerasaurus from the Early Jurassic and in the modern humpback whale.[21] A. parvidens would also have had a similar fin size. In both species, the phalanges of their limbs have large articular facets, featuring elongated coil-shaped bones. In A. quiriquinensis the ulna is slightly shorter than the radius and the tibia is slightly wider than the fibula.[12] During their growth, the humerus and femur of A. quiriquinensis change from a flat capitulum in juveniles to hemispherical shaped heads at adulthood.[20]

Classification

[edit]

Aristonectes was reclassified multiple times throughout its taxonomic history.[12][11] In 1941, Cabrera classified it within the Elasmosauridae based on the shape of the cranial elements,[6] which will prove to be correct decades later.[25][26][21] In 1962, Samuel P. Welles considered Aristonectes to be an indeterminate pliosaur based on its rather enigmatic anatomy.[14] In 1960, Per O. Persson classified it in the Cimoliasauridae, a proposal which he reaffirmed in 1963 on the basis of new observations in the skull.[15] In 1981, David S. Brown moved Aristonectes into the Cryptoclididae based on the presence of 6 to 15 teeth in the premaxilla.[16] From the first revision of the genus carried out in 2003, Gasparini and his colleagues reclassified Aristonectes in the family Elasmosauridae,[9] but this classification was rejected the same year by F. Robin O'Keefe and William Wahl Jr., who placed the genus in the Cimoliasauridae.[27] In 2009, O'Keefe and Hallie P. Street reviewed the validity of Cimoliasauridae, and found that this taxon is a junior synonym of the Elasmosauridae. Therefore, they moved the genera Aristonectes, Kaiwhekea, Kimmerosaurus and Tatenectes into the newly erected family Aristonectidae.[28] In 2011, two years later, O'Keefe and colleagues were skeptical about the classification of Aristonectes and Kaiwhekea with Tatenectes, because their morphologies did not seem to correspond.[29] Otero and colleagues, in 2012, erected the Aristonectinae as a subfamily within the Elasmosauridae. This group is characterized by a very enlarged skull compared to the width of the body, a moderately short neck, and more than 25 teeth in the maxilla,[17] a higher number than in other elasmosaurids.[24] Along with the Elasmosaurinae, the Aristonectinae represents one of two recognized subfamilies within the elasmosaurids.[30] In many phylogenetic analyses, Aristonectes is the most derived genus within the Aristonectinae.[25][26][30][31]

The following cladogram is modified from Otero & Acuña, (2020):[31]

| Elasmosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

[edit]Elasmosaurids were fully adapted to life in the ocean, with streamlined bodies and long paddles that indicate they were active swimmers.[24] The unusual body structure of elasmosaurids would have limited the speed at which they could swim, and their paddles may have moved in a manner similar to the movement of oars rowing, and due to this, could not twist and were thus held rigidly.[32]: 133–135 Plesiosaurs were even believed to have been able to maintain a constant and high body temperature (homeothermy), allowing for sustained swimming.[33]

A 2015 study concluded that locomotion was mostly done by the fore-flippers while the hind-flippers functioned in maneuverability and stability;[34] a 2017 study concluded that the hind-flippers of plesiosaurs produced 60% more thrust and had 40% more efficiency when moving in harmony with the fore-flippers.[35] The paddles of plesiosaurs were so rigid and specialized for swimming that they could not have come on land to lay eggs like sea turtles. Therefore, they probably gave live-birth (viviparity) to their young like some species of sea snakes.[32]: 140 Evidence for live-birth in plesiosaurs is provided by the fossil of an adult Polycotylus with a single fetus inside.[36]

Alimentation

[edit]As with most other plesiosaurs, gastroliths have been found in some specimens of Aristonectes. Among these are 5 elements discovered during the second exhumation of the holotype of A. quiriquinensis,[12] and over 793 in the largest known specimen of the genus, MLP 89-III-3-1, from Antarctica. However, because the latter specimen was found disarticulated (i.e., the bones had moved out of their original anatomical position), it is likely that not all of its gastrolithes have been found.[37][d] The function of gastroliths in plesiosaurs is still controversial.[39] The two most frequently cited hypotheses are their use in buoyancy control and their use as aids for digestion; the latter being the most widely accepted in recent studies.[40][41][42] In 2014, O'Gorman and colleagues analysed the gastrolithes of the Antarctica specimen and concluded that Aristonectes did not select individual stones for ingestion, but swallowed batches of sediment at random that contained stones of various sizes. This is indicated by the lack of size selection: the size distribution of the gastrolites is similar to that expected from a random sample of sediment.[37]

The swimming paddles and tail of A. quiriquinensis resemble those of various modern cetaceans, and lateral movements of the head would have been limited. In addition, the animal's skull has an enlarged mouth that would have allowed the engulfment of a large volume of water. This indicates that A. quiriquinensis fed in benthic zones, mixing prey and sediment at the same time. This type of feeding pattern is also documented in modern gray whales. The presence of decapod crustaceans and fishes within the Quiriquina Formation further reinforces this assertion.[21]

Paleoecology

[edit]

Aristonectes is known from various geological formations of Patagonia and Antarctica that date to the Maastrichtian. It is known from the Quiriquina[12][21] and Dorotea formations in Chile,[43] from the Allen, Jagüel and Lefipán formations in Argentina[11] and from the López de Bertodano Formation in Antarctica.[44][22] The presence of Aristonectes within these formations shows that it would have been endemic in the Weddellian Province, a geographical area that appeared after the isolation of Antarctica.[43] This also indicates that the genus could have migrated regularly between Antarctica and Patagonia, like many current cetaceans.[21] Many bony fishes, cartilaginous fishes, crustaceans and molluscs are known from most localities from which Aristonectes is listed.[45][46][47][43][21][48]

The diversification of plesiosaurs seems to vary from formation to formation. In the Lefipán Formation, only Aristonectes is known,[9][11] while in the Quiriquina Formation it was contemporary with its close relative Wunyelfia.[31] In the Dorotea and López de Bertodano formations, in addition to Aristonectes there are many indeterminate elasmosaurids.[43][44] Exclusively in the López de Bertodano Formation, numerous genera of contemporary mosasaurs have been identified. These include Kaikaifilu, Moanasaurus, Mosasaurus, Liodon and Plioplatecarpus, although the validity of some of these genera is disputed as they are primarily based on isolated teeth.[49][50] Some of these mosasaurs could have attacked the contemporary plesiosaurs of the formation, including Aristonectes.[51]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The body mass estimate per O'Gorman and his colleagues is based on their assumption that Cryptoclidus and Aristonectes would have had similar body proportions.[22]

- ^ In the original 1941 description by Cabrera, the number of teeth in the lower jaw of A. parvidens was estimated at 58,[6] before being proposed at between 60 and 65 in the first revision of the genus carried out by Gasparini et al., (2003).[9] In 2016, O'Gorman reduced this estimate slightly to at least 63 teeth, but did not rule out the possibility that the true number could have been between 63 and 65.[11]

- ^ Only 9 teeth are known in the fossils of A. quiriquinensis,[12][21] while none are known from A. parvidens.[9][11]

- ^ Before the study concerning this specimen published in 2014, only 560 gastroliths were found.[38][12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b José P. O'Gorman; Zulma Gasparini; Leonardo Salgado (2013). "Postcranial morphology of Aristonectes (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia and Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 25 (1): 71–82. Bibcode:2013AntSc..25...71O. doi:10.1017/S0954102012000673. hdl:11336/11188. S2CID 128417881.

- ^ Claude Gay (1848). "Reptiles Fosiles". Zoologia, Vol. 2. Historia Física y Política de Chile [Physical and Political History of Chile] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Paris: Imprenta Maulde y Renou. pp. 130–136.

- ^ Richard Lydekker (1889). Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum. Part II. London: British Museum. p. 222.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke (1895). "Ueber Saurierreste aus den Quiriquina−Schichten" [Concerning Dinosaur Remains from the Quiriquina Strata]. Beiträge zur Geologie und Palaeontologie von Südamerika (in German). 14: 32–63.

- ^ Pavel Pravoslavlev (1918). "Геологическое распространенiе эласмозавровъ" [Geological distribution of Elasmosaurus]. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. VI (in Russian). 12 (17): 1955–1978. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ángel Cabrera (1941). "Un Plesiosaurio nuevo del Cretáceo del Chubut" [A new Plesiosaur of the Cretaceous of Chubut]. Revista del Museo de La Plata (in Spanish). 2 (8): 113–130.

- ^ Edwin H. Colbert (1949). "A new Cretaceous plesiosaur from Venezuela". American Museum Novitates (1420): 1–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1033.3285. hdl:2246/2347.

- ^ Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; David Rubilar-Rogers (2010). "Presence of Mauisaurus in the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of central Chile". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55 (2): 361–364. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0065. S2CID 130819450.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zulma Gasparini; Nathalie Bardet; James E. Martin; Marta Fernandez (2003). "The elasmosaurid plesiosaur Aristonectes Cabrera from the latest Cretaceous of South America and Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 104–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[104:TEPACF]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524298. S2CID 85897767.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

O'Gorman2013was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n José P. O'Gorman (2016). "New insights on the Aristonectes parvidens (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae) holotype: news on an old specimen". Ameghiniana. 52 (4): 397–417. doi:10.5710/AMGH.24.11.2015.2921. hdl:11336/54715. S2CID 89238379.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; Frank Robin O'Keefe; José P. O'Gorman; Wolfgang Stinnesbeck; Mario E. Suárez; David Rubilar-Rogers; Christian Salazar; Luis Arturo Quinzio-Sinn (2014). "Aristonectes quiriquinensis, sp. nov., a new highly derived elasmosaurid from the upper Maastrichtian of central Chile". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (1): 100–125. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34..100O. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.780953. hdl:10915/128448. JSTOR 24523254. S2CID 84729992.

- ^ Ben Creisler (2012). "Ben Creisler's Plesiosaur Pronunciation Guide". Oceans of Kansas. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ a b c Samuel P. Welles (1962). "A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Colombia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs" (PDF). University of California Publications in Geological Sciences. 44 (1): 1–96.

- ^ a b c Per Ove Persson (1963). "A revision of the classification of the Plesiosauria with a synopsis of the stratigraphical and geographical distribution of the group" (PDF). Lunds Universitets Arsskrift. 59 (1): 1–59.

- ^ a b c David S. Brown (1981). "The English Late Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology. 35 (4): 253–347.

- ^ a b Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; David Rubilar-Rogers (2012). "A postcranial skeleton of an elasmosaurid plesiosaur from the Maastrichtian of central Chile, with comments on the affinities of Late Cretaceous plesiosauroids from the Weddellian Biogeographic Province". Cretaceous Research. 37: 89–99. Bibcode:2012CrRes..37...89O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.010. S2CID 129841690.

- ^ Rodrigo A. Otero; José P. O'Gorman (2013). "Identification of the first postcranial skeleton of Aristonectes Cabrera (Plesiosauroidea, Elasmosauridae) from the upper Maastrichtian of the south-eastern Pacific, based on a bivariate graphic analysis". Cretaceous Research. 41: 86–89. Bibcode:2013CrRes..41...86O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.11.001. S2CID 53485462.

- ^ Mario E. Suárez; Omar Fritis (2002). "Nuevo registro de Aristonectes sp. (Plesiosauroidea incertae sedis) del Cretácico Tardío de la Formación Quiriquina, Cocholgüe, Chile" [New record of Aristonectes sp. (Plesiosauroidea incertae sedis) from the Late Cretaceous of the Quiriquina Formation, Cocholgüe, Chile]. Boletín de la Sociedad de Biología de Concepción (in Spanish). 73: 87–93.

- ^ a b Rodrigo A. Oterio; José P. O'Gorman; Norton Hiller (2015). "Reassessment of the upper Maastrichtian material from Chile referred to Mauisaurus Hector, 1874 (Plesiosauroidea: Elasmosauridae) and the taxonomical value of the hemispherical propodial head among austral elasmosaurids". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 58 (3): 252–261. doi:10.1080/00288306.2015.1037775. hdl:11336/53493. S2CID 129018714.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; Frank R. O'keefe (2018). "Osteology of Aristonectes quiriquinensis (Elasmosauridae, Aristonectinae) from the upper Maastrichtian of central Chile". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (1): e1408638. Bibcode:2018JVPal..38E8638O. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1408638. JSTOR 44865847. S2CID 90977078.

- ^ a b c José P. O'Gorman; Sergio N. Santillana; Rodrigo A. Otero; Marcelo A. Reguero (2019). "A giant elasmosaurid (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) from Antarctica: New information on elasmosaurid body size diversity and aristonectine evolutionary scenarios" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 102: 37–58. Bibcode:2019CrRes.102...37O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.05.004. S2CID 181725020.

- ^ Ruizhe Jackevan Zhao (2024). "Body reconstruction and size estimation of plesiosaurs". BioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2024.02.15.578844. S2CID 267760521.

- ^ a b c Sven Sachs; Benjamin P. Kear (2015). "Fossil Focus: Elasmosaurs". www.palaeontologyonline.com. Palaeontology Online. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ a b R. Araújo; Michael J. Polcyn; Johan Lindgren; L. L. Jacobs; A. S. Schulp; O. Mateus; A. Olimpio Gonçalves; M-L. Morais (2015). "New aristonectine elasmosaurid plesiosaur specimens from the Early Maastrichtian of Angola and comments on paedomorphism in plesiosaurs" (PDF). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1017/NJG.2014.43. S2CID 55793835. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-11.

- ^ a b Rodrigo A. Otero (2016). "Taxonomic reassessment of Hydralmosaurus as Styxosaurus: new insights on the elasmosaurid neck evolution throughout the Cretaceous". PeerJ. 4: e1777. doi:10.7717/peerj.1777. PMC 4806632. PMID 27019781.

- ^ F. Robin O'Keefe; William Wahl Jr. (2003). "Preliminary report on the osteology and relationships of a new aberrant cryptocleidoid plesiosaur from the Sundance Formation, Wyoming". Paludicola. 4 (2): 48–68.

- ^ F. Robin O'Keefe; Hallie P. Street (2009). "Osteology Of The cryptoclidoid plesiosaur Tatenectes laramiensis, with comments on the taxonomic status of the Cimoliasauridae" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1671/039.029.0118. S2CID 31924376.

- ^ F. Robin O'Keefe; Hallie P. Street; Benjamin C. Wilhelm; Courtney D. Richards; Helen Zhu (2011). "A new skeleton of the cryptoclidid plesiosaur Tatenectes laramiensis reveals a novel body shape among plesiosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 330–339. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550365. S2CID 54662150.

- ^ a b José P. O'Gorman (2020). "Elasmosaurid phylogeny and paleobiogeography, with a reappraisal of Aphrosaurus furlongi from the Maastrichtian of the Moreno Formation". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (5): e1692025. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1692025. S2CID 215756238.

- ^ a b c Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña (2020). "Wunyelfia maulensis gen. et sp. nov., a new basal aristonectine (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of central Chile". Cretaceous Research. 188: 104651. Bibcode:2021CrRes.11804651O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104651. S2CID 224975253.

- ^ a b Michael J. Everhart (2005). Oceans of Kansas – A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Bloomington: Indiana University. ISBN 978-0-253-34547-9.

- ^ Alexandra Houssaye (2013). "Bone histology of aquatic reptiles: what does it tell us about secondary adaptation to an aquatic life?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 108 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.02002.x. ISSN 0024-4066. S2CID 82741198.

- ^ Shiqiu Liu; Adam S. Smith; Yuting Gu; Jie Tan; C. Karen Liu; Greg Turk (2015). "Computer Simulations Imply Forelimb-Dominated Underwater Flight in Plesiosaurs". PLOS Computational Biology. 11 (12): e1004605. Bibcode:2015PLSCB..11E4605L. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004605. PMC 4684205. PMID 26683221.

- ^ Luke E. Muscutt; Gareth Dyke; Gabriel D. Weymouth; Darren Naish; Colin Palmer; Bharathram Ganapathisubramani (2017). "The four-flipper swimming method of plesiosaurs enabled efficient and effective locomotion". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1861): 20170951. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0951. PMC 5577481. PMID 28855360.

- ^ F. Robin O'Keefe; Luis M.Chiappe (2011). "Viviparity and K-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia)". Science. 333 (6044): 870–873. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..870O. doi:10.1126/science.1205689. PMID 21836013. S2CID 36165835.

- ^ a b José P. O'Gorman; Eduardo B. Olivero; Sergio Santillana; Michael J. Everhart; Marcelo Reguero (2014). "Gastroliths associated with an Aristonectes specimen (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae), López de Bertodano Formation (upper Maastrichtian) Seymour Island (Is. Marambio), Antarctic Peninsula". Cretaceous Research. 50: 228–237. Bibcode:2014CrRes..50..228O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.03.011. hdl:11336/7400. S2CID 129616515.

- ^ José P. O'Gorman; Sergio Santillana; Marcelo Reguero; J. J. Moly (2012), "Primer registro de gastrolitos asociados a un especimen de Aristonectes sp. (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae), Isla Seymour (Is. Marambio), Antartida" [First record of gastroliths associated with a specimen of Aristonectes sp. (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae), Seymour Island (Is. Marambio), Antarctica], in Lepe, Mario; Aravena, Juan Carlos; Villa-Martínez, Rodrigo (eds.), Abriendo Ventanas al Pasado. Libro de Resúmenes del III Simposio - Paleontología en Chile [Opening Windows to the Past. Book of Abstracts of the III Symposium - Paleontology in Chile] (in Spanish), Centro de Estudios del Cuaternario y Antártica del Instituto Antártico Chileno, pp. 121–123, OCLC 1318661175

- ^ Oliver Wings (2007). "A review of gastrolith function with implications for fossil vertebrates and a revised classification". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (1): 1–16.

- ^ Michael J. Everhart (2000). "Gastroliths Associated with Plesiosaur Remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), Western Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 103 (1–2): 64–75. doi:10.2307/3627940. JSTOR 3627940. S2CID 88446437.

- ^ David J. Cicimurri; Michael J. Everhart (2001). "An Elasmosaur with Stomach Contents and Gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous) of Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 104 (3–4): 129–143. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2001)104[0129:AEWSCA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3627807. S2CID 86037286.

- ^ Ignacio A. Cerda; Leonardo Salgado (2008). "Gastrolitos en un plesiosaurio (Sauropterygia) de la Formación Allen (Campaniano-Maastrichtiano), provincia de Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 45 (8): 529–536. ISSN 0002-7014.

- ^ a b c d Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; Christian Salazar; José L. Oyarzún (2015). "New elasmosaurids (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of the Magallanes Basin, Chilean Patagonia: Evidence of a faunal turnover during the Maastrichtian along the Weddellian Biogeographic Province". Andean Geology. 42 (2): 237–267. doi:10.5027/andgeoV42n1-a05. hdl:11336/21148. S2CID 54994060.

- ^ a b José P. O'Gorman; Karen M. Panzeri; Marta S. Fernández; Sergio Santillana; Juan J. Moly; Marcelo Reguero (2018). "A new elasmosaurid from the upper Maastrichtian López de Bertodano Formation: new data on weddellonectian diversity". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 42 (4): 575–586. doi:10.1080/03115518.2017.1339233. hdl:11336/49635. S2CID 134265841.

- ^ Wolfgang Stinnesbeck (1986). "Zu den faunistischen und palökologischen Verhältnissen in der Quiriquina Formation (Maastrichtium) Zentral-Chiles" [On the faunistic and paleoecological conditions in the Quiriquina Formation (Maastrichtian) of central Chile]. Palaeontographica Abteilung A (in German). 194 (4–6): 99–237.

- ^ Agustín Martinelli; Analía Forasiepi (2004). "Late Cretaceous vertebrates from Bajo de Santa Rosa (Allen Formation), Rio Negro province, Argentina, with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur (Titanosauridae)". Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 6 (2): 257–305. doi:10.22179/revmacn.6.88. S2CID 56366877.

- ^ María F. Rodríguez; Héctor A. Leanza; Matías Salvarredy Aranguren (2007). "Provincias del Neuquén, Río Negro y La Pampa" [Provinces of Neuquén, Río Negro and La Pampa]. Servicio Geológico Minero Argentino - Instituto de Geología y Recursos Minerales (in Spanish) (370): 32-35.

- ^ Alberto L. Cione; Sergio Santillana; Soledad Gouiric-Cavalli; Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche; Javier N. Gelfo; Guillermo M. Lopez; Marcelo Reguero (2018). "Before and after the K/Pg extinction in West Antarctica: New marine fish records from Marambio (Seymour) Island". Cretaceous Research. 85: 250–265. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.01.004. hdl:10915/147537. S2CID 133767014.

- ^ Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; David Rubilar-Rogers; Carolina S. Gutstein (2017). "Kaikaifilu hervei gen. et sp. nov., a new large mosasaur (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica". Cretaceous Research. 70: 209–225. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.11.002. S2CID 133320233.

- ^ Pablo Gonzalez Ruiz; Marta S. Fernandez; Marianella Talevi; Juan M. Leardi; Marcelo A. Reguero (2019). "A new Plotosaurini mosasaur skull from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica. Plotosaurini paleogeographic occurrences". Cretaceous Research. 103: 104166. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.06.012. hdl:11336/125124. S2CID 198418273.

- ^ University of Chile (2016-11-07). "A giant predatory lizard swam in Antarctic seas near the end of the dinosaur age". ScienceDaily.

External links

[edit]- Aristonectes information and photos, The Plesiosaur Directory