Union College

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

| |

| Motto | Sous les lois de Minerve nous devenons tous frères et soeurs (French) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Under the laws of Minerva, we all become brothers and sisters |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | February 25, 1795 |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $498 million (2023)[2] |

| President | David R. Harris |

Academic staff | 207 FT/ 20 PT (2023) |

| Undergraduates | 2,082 (2023) |

| Location | , U.S. 42°49′02″N 73°55′48″W / 42.81722°N 73.93000°W |

| Campus | Urban: 120 acres (49 ha), including 8 acres (3.2 ha) of formal gardens |

| Colors | Union garnet[3] |

| Nickname | Garnet Chargers |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Div I – ECAC Hockey Div III – Liberty League |

| Website | www |

| |

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York, United States. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia College. In the 19th century, it became known as the "Mother of Fraternities", as three of the earliest Greek letter societies were established there.[4][5][6] Union began enrolling women in 1970, after 175 years as an all-male institution. The college offers a liberal arts curriculum across 21 academic departments, including ABET-accredited engineering degree programs.

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]

Chartered in 1795,[7] Union was the first non-denominational institution of higher education in the United States, and the second college established in the State of New York.

From 1636 to 1769, only nine institutions of higher education were founded permanently in Colonial America.[a] Most had been founded in association with British religious denominations devoted to the perpetuation of their respective Christian denominations.[8] Union College was to be founded with a broader ecumenical basis.

Only Columbia University, founded in 1754 as King's College,[9] had preceded Union in New York. Twenty-five years later impetus for another institution grew.[10] As democratic cultural changes rose and began to become dominant,[11] old ways, in particular the old purposes and structure of higher education, began to be challenged.[12]

Schenectady had been founded and populated by people originating from the Netherlands. With about 4,000 residents,[13] it was the third largest city in the state, after New York City and Albany. The local Dutch Reformed Church began to show an interest in establishing an academy or college under its auspices there. In 1778, it invited the Rev. Dirck Romeyn of New Jersey to visit.[14] Returning home, he authored a plan in 1782 for such an institution and was summoned two years later[15] to come help found it.

The Schenectady Academy was established in 1785 as the city's first organized school.[16] It immediately flourished, reaching an enrollment of about 100 within a year. By at least 1792 it offered a full four-year college course, as well as one of elementary and practical subjects taught mainly to girls.[17] Attempts to charter the academy as a college with the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York were initially rejected,[13] but in 1794 the school reapplied as "Union College", a name chosen to reflect the resolution of its founders that the school should be free of any specific religious affiliation.[18] The resulting institution was awarded its charter on February 25, 1795 – still celebrated by the college as "Founders' Day".[19]

Nineteenth century

[edit]In 1836, the year of its founding, the Union College Anti-Slavery Society claimed 51 members. It published its Constitution and Preamble, with an address to students—not just those of Union—calling on them to join the abolitionist cause.[20]

Union College was sometimes called Schenectady College in this period.[21]

Seals, mottos, and nickname

[edit]Union chose the modern language French—France was then the most revolutionary of countries—rather than Latin for its motto. The resulting tone of the entire seal is both historically aware and distinctly modern in outlook.[22]

The head of the Roman goddess Minerva (Greek goddess Athena) appeared in the center of an oval. Surrounding it in French was "Sous les lois de Minerve nous devenons tous frères" (English: Under the laws of Minerva, we all become brothers).[23] This was expanded to "et soeurs" (English: "and sisters") in 2015.[24]

Minerva was originally patroness of the arts and crafts,[25] but had over time evolved to become an icon of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. By the late 18th century she had indeed come to represent all of those qualities that might be wished for in a rational, virtuous, prudent, wise, and "scientific" man.[26]

In 2023, the college changed the school's nickname from "Dutchmen" and "Dutchwomen" to "Garnet Chargers" as part of a branding update. Garnet has been the school's official color for 150 years, and the name "chargers" is a reference to "Schenectady's legacy as a leader in electrical technologies."[27]

Presidents

[edit]Union College has had nineteen presidents since its founding in 1795. The school has the distinction of having had the longest serving college or university president in the history of the United States, Eliphalet Nott (62 years).[28][29]

The current president is David R. Harris (2018–present).[30]

Development of the curriculum

[edit]During the first half of the 19th century, students in American colleges would have encountered a very similar course of study, a curriculum with sturdy foundations in the traditional liberal arts.[31] But by the 1820s all of this began to change.[32]

Although Latin and Greek remained a part of the curriculum, new subjects were adopted that offered a more readily apparent application to the busy commercial life of the new nation. Accordingly, French was gradually introduced into the college curriculum, sometimes as a substitute for Greek or Hebrew.[33]

One approach to modernization was the so-called "parallel course of study" in scientific and "literary" subjects.[34] This offered a scientific curriculum in parallel to the classical curriculum, for those students wishing a more modern treatment of modern languages, mathematics, and science, equal in dignity to the traditional course of study.[35]

Union College commenced a parallel scientific curriculum in 1828. Its civil engineering program, introduced in 1845,[36] was the first of its kind at an American liberal arts college.[37] So successful were Union's reform efforts that by 1839 the college had one of the largest faculties in American higher education and an enrollment surpassed only by Yale.[38]

Campus

[edit]

Design

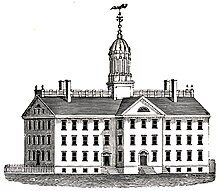

[edit]After Union College received its charter in 1795 the college began conducting classes on the upper floor, while a grammar school continued to be conducted on the lower.[39] It soon became clear that this space would prove inadequate for the growing college. Construction soon began on a three-story building, possibly influenced by Princeton's Nassau Hall,[40] that was occupied in 1804. Two dormitories were constructed nearby.

Eliphalet Nott became college president that year,[41] and envisioned an expanding campus to accommodate a growing school. In 1806 a large tract of land was acquired to the east of the Downtown Schenectady, on a slope up from the Mohawk River and facing nearly due west. In 1812 French architect Joseph-Jacques Ramée was then hired to draw up a comprehensive plan for the new campus.[42] Construction of two of the college buildings proceeded quickly enough to permit occupation in 1814.[43] The Union College campus became the first comprehensively planned college campus in the United States.[44]

Landmarks

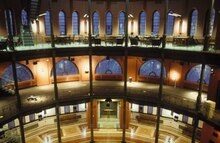

[edit]Nott Memorial: Designed by Edward Tuckerman Potter (class of 1853), this building derived from the central rotunda in the original Ramée Plan. While it was probably intended to be a chapel in its original conception, the Nott Memorial's primary purpose when finally built was aesthetic. It served as the library until 1961 when Schaffer Library was built. Its design bears some resemblance to the Radcliffe Camera at Oxford University. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972[45] and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986.[46] The building was restored between 1993 and 1995 and today is the centerpiece of the campus.[47]

North and South College: The first college buildings using Ramée's plans, the pair were started in 1812 and occupied in 1814. Serving as dormitories, both buildings included faculty residences at each end until well into the 20th century.[48]

Memorial Chapel: Memorial Chapel was constructed between 1924 and 1925 to serve as the central college chapel and to honor Union graduates who lost their lives serving during wartime. The names of Union alumni who died in World War I and World War II appear on its south wall, flanked by portraits of college presidents.[49]

Schaffer Library: Schaffer Library, erected in 1961, was the first building constructed at Union for the sole purpose of housing the college library. Trustee Henry Schaffer donated the majority of funds needed for its construction as well as for a later expansion between 1973 and 1974. The original building was designed by Walker O. Cain of McKim, Mead and White and built by the Hamilton Construction Company. Additional interior work supported by the Schaffer Foundation was done in the 1980s. After structural problems with the 1973–1974 addition developed, a major project to renovate and expand the library was undertaken in the late 1990s. Designed by the firm of Perry, Dean, Rogers, and Partners, the renovation provided space for College Media Services, Writing Center, and a language lab.[50]

Jackson's Garden: Begun in the 1830s by Professor Isaac Jackson of the Mathematics Department, Jackson's Garden comprises 8 acres (3.2 ha) of formal gardens and woodlands. Sited where Ramee's original plans called for a garden, it initially featured a mix of vegetables, shrubs, and flowers – some of which were grown from seeds sent by botanists and botanical enthusiasts from around the world. As early as 1844 it drew the admiration of visitors such as John James Audubon, and evolved into a sweeping retreat for both students and faculty.[51]

Organization and administration

[edit]Board of trustees

[edit]"The Trustees of Union College", a corporate body, has owned the college and been the college's designated legal representative throughout its history.[52] The Board consists of alumni, faculty, students, the president of the college, and others. The governor of the state of New York is also an ex officio member. The Board appoints the president of the college upon vacancy of the position.[53]

The Student Forum

[edit]The Student Forum represents the principal form of student government at Union College. The purpose of the Student Forum is to formulate policies in areas involving the student body. The student body is represented by a president, vice-president of administration, vice-president of finance, vice-president of academics, vice-president of campus life, and vice-president for multicultural affairs. The entire Student Forum includes these officers together with two student trustees and 12 class representatives.[54]

Memberships and affiliations

[edit]Union College belongs to the Liberty League, ECAC Hockey, the Annapolis Group, the Oberlin Group, the Consortium of Liberal Arts Colleges (CLAC), and the New York Six Consortium.[55] Union is also a component of Union University, which also includes Albany Medical College, Albany Law School, the Dudley Observatory, and the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.[56]

Student media

[edit]The Union College radio station, WRUC 89.7, dates from a student project in the fall of 1910, but did not become "live" until 1912.[57] The Union College radio station was among the first wireless transmitters in the country to broadcast regularly scheduled programs.[58] The weekly Concordiensis, the principal newspaper of Union College since 1877, is the thirteenth oldest student newspaper in the United States and the oldest continuously published newspaper in Schenectady.[59]

Academics

[edit]

Most undergraduates are required to complete a minimum of 36 term courses in all programs except engineering, which may require up to 40 courses (in two-degree programs, nine courses beyond the requirements for the professional degrees), and students in the Leadership in Medicine program, which requires around 45–50 courses.[60] The most popular majors, by number out of 488 graduates in 2022, were:[61]

- Economics (82)

- Biological and Biomedical Sciences (46)

- Mechanical Engineering (40)

- Political Science and Government (40)

- Research and Experimental Psychology (36)

- Neuroscience (31)

Admissions

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[62] | 45 |

| Washington Monthly[63] | 85 |

| National | |

| Forbes[64] | 148 |

For the Class of 2027 (enrolling fall 2023), Union College received 9,484 applications and accepted 4,175 (44%).[65] The middle 50% range of SAT scores of enrolled freshmen was 1300-1470 for math + reading, while the middle 50% range of the ACT composite score was 30-33.[65] The average high school grade point average (GPA) was 3.40.[65]

Undergraduate research

[edit]Undergraduate research at Union College had its origin in the first third of the 20th century when chemistry professor Charles Hurd began involving students in his colloid chemistry investigations. Since then, undergraduate research has taken hold in all disciplines at the college, making this endeavor what has been termed "the linchpin" of the Union education. By the mid-1960s several disciplines at Union had established a senior research thesis requirement, and in 1978 the college began funding faculty-mentored student research in all disciplines. This was followed by the creation of funded summer research opportunities, again in all disciplines at the college, in 1986.[66]

Study abroad programs

[edit]Union College makes available a variety of opportunities for formal study outside the United States, the most popular of which are the Terms Abroad Programs.[67] Currently, Terms Abroad are offered for residence and study on nearly every continent, some in cooperation with Hobart and William Smith Colleges. In the 2009–2010 school year, programs were offered in 22 countries or regions around the world.[68]

Every year Union College also offers a variety of mini-terms (three-week programs during the winter break or at the beginning of the summer vacation). In the 2009–2010 school year, mini-terms were offered in 11 regions or countries (including the United States).[69]

Schaffer Library

[edit]

Opened in 1961, Schaffer Library currently makes available onsite about 750,000 books in print as well as electronic formats. The two largest historical, electronic collections are Early English Books Online (EEBO) and Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). The library's print and rare book collections are especially strong in 18th and 19th-century literature, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment. Of particular note is the almost complete preservation of the college's first library, acquired between 1795 and 1799.[70]

Union College belongs to several regional and national consortia that improve access to materials not owned by the college.[71]

Student life

[edit]Fraternity and sorority life

[edit]

The modern fraternity system at American colleges and universities is generally determined as beginning at Union College with the founding of Kappa Alpha Society (1825), Sigma Phi (1827), and Delta Phi (1827).[72][73][74][75][76] Three other surviving national fraternities – Psi Upsilon (1833), Chi Psi (1841), and Theta Delta Chi (1847) – were founded at Union in the next two decades.[77][78][79][80] On account of this fact, Union has been called "The Mother of Fraternities".[5][6][81]

In the fall of 2021, 33% of the college's female students belonged to a sorority and 24% of its male students belonged to a fraternity.[82] In 2010, some 50% of Union's sophomores, juniors, and seniors were members of its twelve Greek-letter organizations.[81]

The six current fraternities at Union are members of the North American Interfraternity Conference, and as such come under the supervision of the Interfraternity Council (IFC).[83] They are: Alpha Delta Phi, Chi Psi, Kappa Alpha Society, Sigma Chi, Sigma Phi, and Theta Delta Chi.[84][80][85] A chapter of the co-ed community service oriented fraternity Alpha Phi Omega also exists on campus.[86] Among dormant fraternities with active alumni, Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity maintained a chapter on campus from 1888 to 1997.[87][80] The College Panhellenic Council (CPC) is the governing body for member sororities, of which the National Panhellenic Council (NPC) is the parent organization.[83] There are three CPC sororities at Union: Delta Phi Epsilon, Gamma Phi Beta and Sigma Delta Tau.[84][80][88] The Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) is the governing body for organizations under the supervision of the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC), National Association of Latino Fraternal Organizations (NALFO), or for any local organizations that fall under the category.[83] These organizations are Alpha Phi Alpha, Phi Iota Alpha, Iota Phi Theta, Lambda Pi Chi, and Omega Phi Beta.[84][89][80]

Minerva system

[edit]After issues with binge-drinking, and excessive vandalism, Union College's board suspended greek life in 2004. This ban removed exclusive rights from sororities and fraternities to any residence on campus, allowing Union College to regain partial ownership of the houses. While not affecting the majority of Greek students, who already shared housing with other students, it displaced the members of five of the most visible fraternities, who enjoyed what the college considered prime real estate in mansions at the heart of the campus. The move was cast as a means of enhancing Union’s social and cultural life, which college officials reported to be overwhelmingly Greek.[90][73][81] This initiative was, and remains, a controversial step by the college.[91] A non-residential "house system" was created and funded, establishing buildings to serve as intellectual, social, and cultural centers for resident and non-resident members. All incoming students are randomly assigned to one of the seven Minerva Houses. An Office of Minerva Programs was created to coordinate and supervise Minerva activities.[92]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Mandeville Gallery

[edit]The Mandeville Gallery presents an annual Art Installation Series in partnership with the Schaffer Library.[93] The Art Installation Series features contemporary artists who visit campus and create a site-specific installation piece for the library's Learning Commons.[94]

The Wikoff Student Gallery, on the third floor of the Nott Memorial, is dedicated to showing work by current, full-time Union College students.[95]

The college owns over 3,000 works of art and artifacts which comprise its Permanent Collection, most of which are available for use by faculty and students in support of teaching and research.[96]

Yulman Theater

[edit]The Department of Music sponsors lectures, performances, recitals, and workshops by visiting artists at numerous campus venues, including the Taylor Music Center and Memorial Chapel. Union College jazz, choral and orchestral groups, a taiko ensemble, and three student a cappella groups perform regularly. The college's chamber music series performs at the Memorial Chapel.[97]

The Department of Theater and Dance offers several major theatrical productions as well as staged readings, student performances, guest appearances, and other shows throughout the school year.[98]

Athletics

[edit]

Intercollegiate competition is offered in 26 sports; for men, in baseball, basketball, crew, cross-country, football, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, swimming, tennis, and indoor and outdoor track; and for women, in basketball, crew, cross-country, field hockey, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, softball, swimming, tennis, indoor and outdoor track, and volleyball. Originally a founding member of the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), Union today participates in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), the Liberty League, ECAC Hockey and the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC). Men's and women's ice hockey compete at the NCAA Division I level; all other sports compete at the NCAA Division III level.[99]

All club sports are administered through the student activities office. The most active and popular clubs are baseball, bowling, fencing, golf, ice hockey, karate, rugby, skiing, volleyball, and ultimate frisbee. An extensive intramural program is offered in a wide range of sports along with noncredit physical education classes as part of the wellness program.[99]

Facilities include the Frank L. Messa Rink at the Achilles Center, the David Breazzano Fitness Center, the Travis J. Clark Strength Training Facility, the David A. Viniar Athletic Center, and Frank Bailey Field.[99]

Union has hosted the two longest games in NCAA Men's Hockey History, losing both by identical 3-2 scores: The longest game in NCAA hockey history was played on March 12, 2010. Quinnipiac University defeated Union College, 3–2, in the ECAC Hockey League Quarter-Finals after 90:22 of overtime. Greg Holt scored the winning goal just after 1:00 am local time. The second-longest game in NCAA hockey history was played on March 5, 2006. Yale University defeated Union College, 3–2, in the ECAC Hockey League first-round playoff game after 81:35 of overtime. David Meckler scored the winning goal with Yale shorthanded.[100]

The Union football team went undefeated during the 1989 regular season, going 10–0. They lost to Dayton in the Amos Alonzo Stagg Bowl for the NCAA Division III Football Championship, 17–7.[101]

Notable alumni

[edit]- Chester A. Arthur[102] (1848), 21st president of the United States

- William H. Seward[103] (1820), Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln, Governor of New York, and architect of the Alaska Purchase from Russia

- George Westinghouse,[104] engineer, prolific inventor and industrialist

- Martin Jay (1965), prominent American intellectual historian, author of several works, professor at University of California, Berkeley, member of the American Philosophical Society, and fellow at the American Academy in Berlin.[105]

- Andrea Barrett (1974), winner of the National Book Award (for Ship Fever) and the Pulitzer Prize for works of fiction.

- Baruch Samuel Blumberg (1946)[106] winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Jimmy Carter, 39th president of the United States, studied nuclear physics at the Graduate School.

- Alan F. Horn (1964),[107] the chairman of Walt Disney Studios, and former president and COO of Warner Bros.;

- Fitz Hugh Ludlow[108] (1856), author of The Hashish Eater;

- Howard Simons (1951),[109] managing editor of The Washington Post during the Watergate era;

- Rich Templeton (1980) engineer, former Chief Executive Officer Texas Instruments Instruments, philanthropist

- Nikki Stone (1995)[110] winner of a gold medal in the 1998 Winter Olympics for aerial skiing

- Jake Fishman (2018)[111] American-Israeli Major League Baseball pitcher for the Miami Marlins and in the 2020 Olympics for Team Israel, the only Union player to ever be drafted in the MLB draft.

-

Gordon Gould (1941), physicist credited with the invention of the laser

-

Nobel Laureate Baruch Samuel Blumberg (1946)

-

Neil Abercrombie (1959), seventh governor of Hawaii

See also

[edit]- Union College Men's Glee Club

- List of colleges and universities in New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Schenectady County, New York

- List of Union College alumni

Notes

[edit]a ^ Harvard University, The College of William and Mary, Yale University, Princeton University, Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania, Brown University, Rutgers University, and Dartmouth College.[8]

b ^ Washington College, Washington and Lee University, Hampden–Sydney College, Transylvania University, Dickinson College, St. John's College, University of Georgia, College of Charleston, Franklin & Marshall College, University of Vermont, Williams College, Bowdoin College, Tusculum College, University of Tennessee, University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill) and Union College.[112]

References

[edit]- ^ center, member. "Member Center". Archived from the original on November 9, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "U.S. and Canadian 2023 NCSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2023 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY22 to FY23, and FY23 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student" (XLSX). National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and TIAA. February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ "Colors - Communications - Union College". Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 304

- ^ a b Stevens, Albert Clark (1899). The Cyclopædia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Authentic Information and the Results of Original Investigation as to ... More Than Six Hundred Secret Societies in the United States. New York: Hamilton Printing and Publishing Company. pp. 333 and 351 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Work of Union College; Hundreds of Distinguished Men Among Its Graduates. Incorporated One Hundred Years. The Present Beautiful Site of Two Hundred Acres Secured in 1812 -- "The Mother of Fraternities."" (PDF). The New York Times. June 21, 1895. p. 9. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Fortenbaugh (1978), p. 3

- ^ a b Tewksbury (1932), p. 59

- ^ A History of Columbia University, 1754–1904. New York: Columbia University Press. 1902. p. 1.

- ^ Fox (1945), p. 10

- ^ Rudolph (1965), p. 34

- ^ Boorstin (1965), p. 153

- ^ a b Somers (2003), p. 296

- ^ Pearson (1880/1980), p. 119

- ^ Fortenbaugh (1978), p. 36

- ^ Neisular (1964), p. 20

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 629

- ^ Raymond (1907), p. 1:34

- ^ Yates (1902), p. 423

- ^ "First annual report of the Union College Anti-Slavery Society: with an address to students, and an appendix". Schenectady, New York. 1836. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ College of Physicians of Philadelphia (1846). Summary of the Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Vol. 1. Waverly Press. p. 88.

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 636; See also Fortenbaugh, passim.

- ^ Fortenbaugh (1978), p. 73

- ^ "Union's age-old motto gets a modern makeover". Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Altheim (1938), p. 265

- ^ King (1750), p. 123

- ^ Singelais, Mark (August 3, 2023). "Union changes nickname to Garnet Chargers". Albany Times Union. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Yates (1902), p. 428

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 510

- ^ "David R. Harris". Union College. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Schmidt (1957), p. 52, 54

- ^ Rudolph (1965), p. 113

- ^ Rudolph (1977), p. 51

- ^ Butts (1939), p. 129

- ^ Rudolph (1965), p. 114

- ^ Hough (1885), p. 160

- ^ O'Donnell, Paul (February 21, 2020). "Texas Instruments CEO Rich Templeton, his wife donate $51 million to college where they met". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Guralnick (1975), p. 38

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 630

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 789

- ^ Hislop (1971), p. 139

- ^ Tunnard (1964), p. 10

- ^ Turner (1996), p. 189

- ^ Turner (1996), p. 190

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Nott Memorial Hall". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 17, 2007. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 518

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 505

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 486

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 627

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 411

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 745

- ^ "Union College, Board of Trustees". Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ "Union College Student Forum". Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ "Union and other colleges form New York Six Consortium". Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ "Union University". Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 593

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 594

- ^ Somers (2003), p. 184

- ^ Union College Academic Register, 2008–2009. Union College. p. 3.

- ^ "Union College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Union College Common Data Set 2018-2019". Union College. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Undergraduate Research". Union College. Archived from the original on September 5, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ "International Programs - Union College". Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ "Union College, International Programs: Terms Abroad". Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ "Union College, International Programs: Mini-Terms". Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Dibbell, Jeremy B. (2008). ""A Library of the Most Celebrated & Approved Authors": The First Purchase Collection of Union College". Libraries & the Cultural Record. Vol. 43, no. 4. pp. 367–396. doi:10.1353/lac.0.0046.

- ^ "Connect NY". Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ Becque, Fran (October 6, 2014). "In a NY State of Mind...The Union Triad and Other Thoughts". Fraternity History & More. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Confessore, Nicholas (July 29, 2007). "Fraternizing: Students in Residence". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. pp. 171-172.Retrieved 2023-08-08 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. p. 334.Retrieved 2023-08-08 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. p. 135. Retrieved 2023-08-08 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. p. 294.Retrieved 2023-08-08 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. p. 112. hdl:2027/inu.30000011324468. Retrieved August 8, 2023 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ Brown, James T., ed. (1923). "Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities; A Descriptive Analysis of the Fraternity System in the Colleges of the United States" (10th ed.). New York: James T. Brown, editor and publisher. p. 364.Retrieved 2023-08-08 – via Hathi Trust.

- ^ a b c d e Lurding, Carroll and Becque, Fran. (August 5, 2023) "Union College", Almanac of Fraternities and Sororities. Urbana: University of Illinois. Accessed August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Yale Daily News (June 23, 2009). The Insider's Guide to the Colleges, 2010: Students on Campus Tell You What You Really Want to Know (36th ed.). New York: St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 601. ISBN 978-1-4299-3531-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Union College (NY) Student Life". U.S. New & World Report. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Chen, Tracy (September 22, 2022). "Greek Life office gives advice to students". The Concordiensis. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life". Fraternity and Sorority Life. Union College. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "OFSL: Interfraternity Council". Union College Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "OFSL: Greek Service and Leadership". Union College Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Rand, Frank Prentice; Ralph Watts; James E. Sefton (1993), All The Phi Sigs - A History, Grand Chapter of Phi Sigma Kappa

- ^ "OFSL: Panhellenic Council". Union College Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "OFSL: Multicultural Greek Council". Union College Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Brownstein, Andrew. "Union College's Fraternities Lose Exclusive Rights to Their Houses". Chronicle. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Farrell, Elizabeth (February 24, 2006). "Putting Fraternities in Their Place". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "Union College, Student Life: Minerva Programs". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ "Schaffer Library". Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "About the Art Installation Series - Mandeville Gallery". muse.union.edu. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "Union College: Mandeville Gallery". Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ "Union College Permanent Collection". Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ "Union College: Music". Archived from the original on July 13, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ "Union College: Theater & Dance". Archived from the original on June 7, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Union College Athletics". Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "Where Hockey's More Than Another Tradition". ECAC Hockey. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ MacAdam, Mike (December 11, 1989). "Dayton Defeats Union, Claims NCAA Title, 17-7". Schenectady (N.Y.) Gazette. Gazette Newspapers. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2016 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ DAB, 1:373

- ^ DAB, 16:615

- ^ "Happy Birthday, George Westinghouse | Union College News Archives". muse.union.edu. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Martin Jay".

- ^ "Baruch Blumberg '46, winner of Nobel Prize, dies". Union College. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Union College Notables Archive". Union College Schaeffer Library. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ DAB, 11:491

- ^ "Howard Simons Class of 1951". Union College - Schaeffer Library Collections. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Nikki Stone Class of 1995". Union College Schaeffer Library Collection. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Stothers, Patrick (March 15, 2017). "Spring training has been a reality check for Fishman".

- ^ Tewksbury (1932), p. 60

Bibliography

[edit]- ANB: American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999. OCLC 39182280.

- Boorstin, Daniel J. (1965). The Americans: The National Experience. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-517-16415-9. OCLC 360759.

- Butts, R. Freeman (1939). The College Charts Its Course. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-405-03699-X. OCLC 603810.

- DAB: Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Scribner. 1928. OCLC 4171403.

- Demarest, William H. S. (1924). A History of Rutgers College, 1766–1924. New Brunswick: Rutgers College. OCLC 785305.

- Ferm, Robert L. (1976). Jonathan Edwards the Younger. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-3485-X.

- Fortenbaugh, Samuel B. Jr. (1978). In Order to Form a More Perfect Union: An Inquiry into the Origins of a College. Schenectady: Union College Press. ISBN 0-912756-06-3.

- Fox, Dixon Ryan (1945). Union College: An Unfinished History. Schenectady, New York: Union College. OCLC 4676869.

- Guralnick, Stanley M. (1975). Science and the Ante-Bellum College. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-109-4.

- Hislop, Codman (1971). Eliphalet Nott. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-4037-4.

- Hough, Franklin B. (1885). Historical and Statistical Record of the University of the State of New York. Albany: Weed, Parsons. OCLC 473881227.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Neisular, Jeanette G. (1964). The History of Education in Schenectady. Schenectady: Schenectady Board of Education. OCLC 18477246.

- Pearson, Jonathan (1980). Three Centuries: The History of the First Reformed Church of Schenectady, 1680–1980. Schenectady: The First Reformed Church of Schenectady. OCLC 483709158.

- Randall, Henry S. (1858). The Life of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Derby and Jackson. ISBN 0-8050-1577-9. OCLC 933758.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Raymond, Andrew Van Vranken (1907). Union University. New York: Lewis Publishing Company. ISBN 0-9519312-2-9. OCLC 11901093.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Rudolph, Frederick (1965). The American College and University. New York: Alfred Knopf. ISBN 0-201-14835-8. OCLC 176662.

- Rudolph, Frederick (1977). Curriculum: A History of the American Undergraduate Course of Study Since 1636. San Francisco: Josey-Bass. ISBN 0-87589-358-9.

- Schmidt, George P. (1957). The Liberal Arts College. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-534-93501-X. OCLC 254359957.

- Sherwood, Sidney (1900). The University of the State of New York: History of Higher Education in the State of New York. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 3123002.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Somers, Wayne, ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Union College History. Schenectady, New York: Union College. ISBN 0-912756-31-4.

- Tewksbury, Donald G. (1932). The Founding of American Colleges and Universities Before the Civil War. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. OCLC 76620.

- Tunnard, Christopher (1964). Joseph Jacques Ramée: Architect of Union College. Schenectady, New York: Union College. OCLC 5291278.

- Turner, Paul V. (1984). Campus: An American Planning Tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-20047-3.

- Turner, Paul V. (1996). Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49552-0.

- Wills, Garry (2002). Mr. Jefferson's University. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-6531-9. OCLC 97814677.

- Yates, Austin A. (1902). Schenectady County, New York: Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. New York: New York History Company. ISBN 1-153-14534-0. OCLC 18738526.

Further reading

[edit]- Hough, Franklin B. (1876). Historical Sketch of Union College. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 61597023.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Huntley, C. William (1985). Thirty Years in the Life of a College. Schenectady, New York: Union College. OCLC 15201599.

- Larrabee, Harold A. (1934). Joseph Jacques Ramée and America's First Unified College Plan. New York: American Society of the French Legion of Honor. OCLC 29132611.

- Van Santvoord, Cornelius (1876). Memoirs of Eliphalet Nott, for Sixty-Two Years President of Union College. New York: Sheldon. OCLC 3325463.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Waldron, Charles (1954). The Union College I Remember, 1902–1946. Boston: privately printed. OCLC 916746.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Union College Athletics

- Concordiensis archives (1887–2008) at NY State Historic Newspapers

- Union College (New York)

- 1795 establishments in New York (state)

- Education in Capital District (New York)

- Education in Schenectady, New York

- Educational institutions established in 1795

- Joseph-Jacques Ramée buildings

- Liberal arts colleges in New York (state)

- Private universities and colleges in New York (state)