TARDIS

| TARDIS | |

|---|---|

| Doctor Who television series element | |

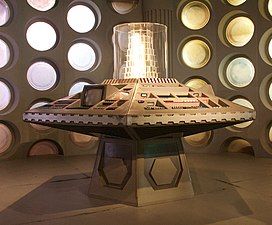

Prop for the Doctor's TARDIS used between 2010 and 2017 | |

| Publisher | BBC |

| First appearance | An Unearthly Child (1963) |

| Created by | |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Time machine/spacecraft |

| Function | Travels through time and space |

| Traits and abilities | Can change its outer dimensions and inner layout, impregnable, telepathic |

| Affiliation | |

The TARDIS (/ˈtɑːrdɪs/; acronym for "Time And Relative Dimension(s) In Space") is a fictional hybrid of a time machine and spacecraft that appears in the British science fiction television series Doctor Who and its various spin-offs. While a TARDIS is capable of disguising itself, the exterior appearance of the Doctor's TARDIS typically mimics a police box, an obsolete type of telephone kiosk that was once commonly seen on streets in Britain in the 1940s and 50s. Paradoxically, its interior is shown as being much larger than its exterior, commonly described as being "bigger on the inside".

Due to the significance of Doctor Who in popular British culture, the shape of the police box is now more strongly associated with the TARDIS than its real-world inspiration. The name and design of the TARDIS is a registered trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), although the design was originally created by the Metropolitan Police Service.[1][2]

Name

[edit]TARDIS is an acronym of "Time And Relative Dimension in Space". The word "Dimension" is alternatively rendered in the plural. The first story, An Unearthly Child (1963), used the singular "Dimension". The 1964 novelisation Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks used "Dimensions" for the first time and the 1965 serial The Time Meddler introduced the plural in the television series – although the script had it as singular, actor Maureen O'Brien changed it to "Dimensions".[3] Both continued to be used during the classic series; in "Rose" (2005), the Ninth Doctor uses the singular (although this was a decision of actor Christopher Eccleston—[4] the line was plural in the script for the episode).[5] The acronym was explained in the first episode of the show, An Unearthly Child (1963), in which the Doctor's granddaughter Susan claims to have made it up herself.[6] Despite this, the term is used commonly by other Time Lords to refer to both the Doctor's and their own time ships.[nb 1]

Generally, "TARDIS" is written in all uppercase letters, but may also be written in title case as "Tardis". The word "Tardis" first appeared in print in the Christmas 1963 edition of Radio Times, which refers to "the space-time ship Tardis".[7]

Description

[edit]

In the fictional universe of the Doctor Who television show, TARDISes are space- and time-travel vehicles of the Time Lords, beings from the planet Gallifrey. Although many TARDISes exist and are sometimes seen on-screen, the television show mainly features a single TARDIS used by the show's protagonist, a Time Lord who goes by the name of the Doctor.[8]

TARDISes are built with a "chameleon circuit", a type of camouflage technology that changes the exterior form of the ship to blend into the environment of whatever time or place it lands in. The Doctor's TARDIS always resembles a 1960s London police box, an object that was very common in Britain at the time of the show's first broadcast.[9] Owing to a malfunction in the chameleon circuit after the events of the first episode of the show, An Unearthly Child, the Doctor's TARDIS is stuck in the same disguise for a long period.[8][10] The Doctor has attempted to repair the chameleon circuit, unsuccessfully in Logopolis (1981) and with only temporary success in Attack of the Cybermen (1985). In the 2005 television story "Boom Town", the Doctor reveals that he has stopped trying to repair the circuit as he has become fond of its appearance. The other TARDISes that appear in the series have chameleon circuits that are fully functional.[11]

While the exterior is of limited size, the TARDIS is famously "bigger on the inside". Behind the police box doors lies a large control room, at the centre of which is a console for operating the TARDIS. In the middle of the console is a moving tubular device called a time rotor. The presence of a physically larger space contained within the police box is explained as "dimensionally transcendental", with the interior being a whole separate dimension containing an infinite number of rooms, corridors and storage spaces, all of which can change their appearance and configuration.[12][13][10] The TARDIS also allows the Doctor and others to communicate with people who speak languages other than their own, as well as turn all written languages to English. The "translation circuit" (occasionally called the "translation matrix") was first explored in The Masque of Mandragora (1976), as the Doctor explained to his companion, Sarah Jane, "Well, I've taken you to some strange places before and you've never asked how you understood the local language. It's a Time Lord's gift I allow you to share. But tonight, when you asked me how you understood Italian, I realised your mind had been taken over." The translation circuit has also been explored in comparison with real-world machine translation, with researchers Mark Halley and Lynne Bowker concluding that "when it comes to the science of translation technology, Doctor Who gets it wrong more often than it gets it right. However, perhaps we can forgive the artistic license if we recognise that, as in other science fiction works, the presentation of some type of ubiquitous translation tool is necessary to explain to the audience how people from other countries, time periods, and even other worlds, can understand each other and indeed appear to speak (mostly) flawless English."[14]

The TARDIS also has other special abilities: it can produce a large, invisible air bubble around its exterior that allows occupants to survive in an area that lacks oxygen as long as they are close to it and in one episode, it can create a bridge tunnel that occupants can use to cross over to out-of-reach areas such as another ship.[15] The TARDIS is also shown to be strong enough to tow other ships and planets[16] and can even withstand black holes.[17] It is also able to generate a "perception filter" that causes people to ignore it, thinking that it is normal.[18] In another episode, it also has a function called the Hostile Action Displacement System (H.A.D.S), which makes it teleport away if it senses danger and will not return until after the danger is dealt with.[19] In the 60th anniversary special "The Giggle", the Fifteenth Doctor created a copy of TARDIS for the Fourteenth Doctor. Responding to speculation that the Fifteenth Doctor's TARDIS was a "new" one, Russell T Davies said that it is, in fact, the original.[20]

Conceptual history

[edit]Exterior design

[edit]When Doctor Who was being developed in 1963 the production staff discussed what the Doctor's time machine would look like. To keep the design within budget[21] it was decided to make the outside resemble a police telephone box, a common piece of street furniture that had originally been designed in the 1920s by the Scottish architect Gilbert Mackenzie Trench.[22] The idea for the police-box disguise came from a BBC staff writer, Anthony Coburn, who rewrote the programme's first episode from a draft by C. E. Webber.[23][24] While there is no known precedent for this notion, a November 1960 episode of the popular radio comedy show Beyond Our Ken included a sketch featuring a time machine described as "a tall telephone box".[25]

The concept of a cloaking mechanism (later referred to as the "chameleon circuit") was devised to explain this. In the first episode, An Unearthly Child (1963), the TARDIS is first seen hidden in a London scrapyard in 1963, and after travelling back in time ("The Cave of Skulls") to the Paleolithic era, the police box exterior persists.[9] In a subsequent story, The Time Meddler (1965), the First Doctor explains that the TARDIS should automatically adopt a disguise, such as a howdah (a carrier on the back of an Indian elephant in the Indian Mutiny) or a rock on a beach.[26]

Accounts differ as to the origin of the police box prop. While the BBC asserts that it was constructed specially for Doctor Who,[27] it has been claimed that the box was a reused prop from the BBC television police dramas Z-Cars or Dixon of Dock Green (a claim later repeated by Doctor Who producer Steven Moffat).[28][29]

The dimensions and colour of the TARDIS police box props used in the series have changed many times, as a result of damage and the requirements of the show,[30][31] and none of the BBC props has been a faithful replica of the original MacKenzie Trench model. Numerous details have been altered over time, including the shape of the roof, the signage, the shade of blue paint, the presence of a St John Ambulance emblem and the overall height of the box.[32] The original prop remained in use for around 13 years until it collapsed – reportedly on Elisabeth Sladen's head. A new prop was introduced for The Masque of Mandragora in 1976, and there have been at least six versions in total.[33] The evolution of the prop design was referenced on-screen in the episode "Blink" (2007), when the character Detective Inspector Shipton says the TARDIS "isn't a real [police box]. The phone's just a dummy, and the windows are the wrong size."[nb 2]

Interior design

[edit]The TARDIS console room was designed for the first episode by set designer Peter Brachacki and was unusually large for a BBC production of this time. It was noted for its innovative, gleaming white "futuristic" appearance.[35][30]

Like the police box prop, the set design of the TARDIS interior has evolved over the years. From the inception of the show in 1963 up until the end of the "classic series" in 1989, the design of the TARDIS console room remained largely unchanged from Brachacki's original set, a brightly lit white chamber, lined with a pattern of roundels on the walls and with a central hexagonal console which contained a cylindrical "time rotor" that moved when the TARDIS was in transit. Numerous alterations were made to the central console and to the layout, but the overall concept remained constant. In Season 14 (1976–77), a dark wood-panelled "Control Room Number 2" was briefly used for a few episodes, but the white console room set was reinstated in Season 15, due to damage to the set. After the cancellation of the television show, a radically redesigned TARDIS set was used in the 1996 TV movie, heralding a move to a more steampunk-inspired set design, which later influenced the set design in the revived series from 2005 onwards.[36]

- The evolving TARDIS interior sets 1963–2018

-

The original 1963 set (2014 reproduction)

-

The console room set used from 1977 to 1983

-

The updated console room set used from 1983 to 1989

-

The redesigned set from 2005 to 2010

-

The TARDIS interior used by the Eleventh Doctor (Matt Smith) from 2010 to 2012

-

The TARDIS interior from 2012 to 2017, as it appeared during the era of the Twelfth Doctor (Peter Capaldi)

Depiction of time travel

[edit]The production team conceived of the TARDIS travelling by dematerialising at one point and rematerialising elsewhere, although sometimes in the series it is shown also to be capable of conventional space travel. In the 2006 Christmas special, "The Runaway Bride", the Doctor remarks that for a spaceship, the TARDIS does remarkably little flying. The ability to travel simply by fading into and out of different locations became one of the trademarks of the show, allowing for a great deal of versatility in setting and storytelling without a large expense in special effects. The distinctive accompanying sound effect – a cyclic wheezing, groaning noise – was originally created in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop by sound technician Brian Hodgson by recording on tape the sound of his mother's house key scraping up and down the strings of an old piano. Hodgson then re-recorded the sound by changing the tape speed up and down and splicing the altered sounds together.[37][38] When employed in the series, the sound is usually synchronised with the flashing light on top of the police box, or the fade-in and fade-out effects of a TARDIS. Writer Patrick Ness has described the ship's distinctive dematerialisation noise as "a kind of haunted grinding sound",[39] while the Doctor Who Magazine comic strips traditionally use the onomatopoeic phrase "vworp vworp vworp".[40]

Other appearances

[edit]Television spin-offs

[edit]The sound of the Doctor's TARDIS featured in the final scene of the Torchwood episode "End of Days" (2007). As Torchwood Three's hub is situated at a rift of temporal energy, the Doctor often appears on Roald Dahl Plass directly above it in order to recharge the TARDIS.[41] In the episode, Jack Harkness hears the tell-tale sound of the engines, smiles and afterwards is nowhere to be found; the scene picks up in the cold open of the Doctor Who episode "Utopia" (2007) in which Jack runs to and holds onto the TARDIS just before it disappears.

Former companion Sarah Jane Smith has a diagram of the TARDIS in her attic, as shown in The Sarah Jane Adventures episode "Invasion of the Bane" (2007). In the two-part serial The Temptation of Sarah Jane Smith (2008), Sarah Jane becomes trapped in 1951 and briefly mistakes an actual police public call box for the Doctor's TARDIS (the moment is even heralded by the Doctor's musical cue, frequently used in the revived series). It makes a full appearance in The Wedding of Sarah Jane Smith (2009), in which the Doctor briefly welcomes Sarah Jane's three adolescent companions into the control room. It then serves as a backdrop for the farewell scene between Sarah Jane and the Tenth Doctor, which echoed nearly word-for-word her final exchange with the Fourth Doctor aboard the TARDIS in 1976. It reappears in Death of the Doctor (2010), where it is stolen by the Shansheeth[broken anchor] who try to use it as an immortality machine, and transports Sarah Jane, Jo Grant and their adolescent companions (Rani Chandra, Clyde Langer and Santiago Jones).

Theatrical films

[edit]The TARDIS appears in the two film productions, Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965) and Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966). In both films the Doctor, played by Peter Cushing, is an eccentric scientist who invented the TARDIS himself.[42]

Cultural impact

[edit]

Merchandising

[edit]As one of the most recognisable images connected with Doctor Who, the TARDIS has appeared on numerous items of merchandise associated with the programme. TARDIS scale models of various sizes have been manufactured to accompany other Doctor Who dolls and action figures, some with sound effects included. Fan-built full-size models of the police box are also common. There have been TARDIS-shaped video games, play tents for children, toy boxes, cookie jars, book ends, key chains, and even a police-box-shaped bottle for a TARDIS bubble bath. The 1993 VHS release of The Trial of a Time Lord was contained in a special-edition tin shaped like the TARDIS.

With the 2005 series revival, a variety of TARDIS-shaped merchandise has been produced, including a TARDIS coin box, TARDIS figure toy set, a TARDIS that detects the ring signal from a mobile phone and flashes when an incoming call is detected, TARDIS-shaped wardrobes and DVD cabinets, and a USB hub in the shape of the TARDIS.[43] The complete 2005 season DVD box set, released in November 2005, was issued in packaging that resembled the TARDIS.

One of the original-model TARDISes used in the television series' production in the 1970s was sold at auction in December 2005 for £10,800.[44]

BBC trademark

[edit]In 1996 the BBC applied to the UK Intellectual Property Office to register the TARDIS as a trademark.[45] This was challenged by the Metropolitan Police, who felt that they owned the rights to the police box image. However, the Patent Office found that there was no evidence that the Metropolitan Police – or any other police force – had ever registered the image as a trademark. In addition, the BBC had been selling merchandise based on the image for over three decades without complaint by the police. The Patent Office issued a ruling in favour of the BBC in 2002.[46][47]

The word TARDIS is listed in the Oxford English Dictionary.[48]

Legacy police boxes

[edit]

A number of legacy police boxes are still standing on streets around the United Kingdom. Although now no longer used for their original function, many have been repurposed as coffee kiosks, and are often affectionately referred to as TARDISes.[49][50] A police box in the Somerton area of Newport in South Wales is known as the Somerton TARDIS.[51]

In science and computing

[edit]An asteroid discovered in 1984 by astronomer Brian A. Skiff was named 3325 TARDIS on account of its cuboid appearance.[52] A number of geological features on Charon, the largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto, have been named after mythological or fictional vessels, and one is named the Tardis Chasma.[53]

A data storage manufacturer called tarDISK markets a flash memory drive for Apple MacBook which it claims is "bigger on the inside". They also claim native integration with Apple's Time Machine backup software.[54][55]

The European Space Agency has sent 3,000 tardigrades ("water bears") into orbit on the outside of a rocket; 32% survived. The experiment was named Tardigrades in Space, or Tardis.[56]

In popular culture

[edit]

Cultural references to the TARDIS are many and varied.

In music, The KLF (performing as "The Timelords") released a novelty pop single in 1988 entitled "Doctorin' the Tardis". The record reached number one in the UK Singles Chart and had chart success worldwide. It was a reworking of several songs (principally Gary Glitter's "Rock and Roll Part 2", The Sweet's "Block Buster!" and the Doctor Who theme music) with lyrics referencing Doctor Who, specifically the TARDIS.[57] In 2007, the British rock band Radiohead included the song "Up on the Ladder" on their album In Rainbows which begins with the line "I'm stuck in the TARDIS".[58][59]

In 2001, Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Wallinger created a piece or artwork entitled Time and Relative Dimensions in Space that is structurally a police box shape faced with mirrors.[60][61] The BBC website describes it as "recent proof of [the TARDIS'] enduring legacy".[13]

In July 2014, the Monty Python comedy troupe opened their reunion show, Monty Python Live (Mostly), with a trademark animation featuring the Tardis – dubbed the "retardis" – flying through space before the Pythons came on stage.[62][63]

In film, the TARDIS makes a cameo appearance in a number of productions, including Iron Sky (2012)[64] and The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part (2019).[65] The TARDIS has also featured within the gameplay of a number of popular video games, including Lego Dimensions[66] and Fortnite: Battle Royale.[67]

To promote the Barbie film released in July 2023, a pink TARDIS was unveiled next to Tower Bridge in London on 11 July, as Ncuti Gatwa would appear in both Barbie as a Ken and in Doctor Who as the Fifteenth Doctor.[68]

Other references to the TARDIS have included a $2 silver commemorative coin depicting the TARDIS, issued on Niue Island in the South Pacific Ocean by the Perth Mint to mark the 50th anniversary of the Doctor Who television show;[69] and Tardis Environmental, a British sewage company, in reference to the similarity of their portable toilets to a police box.[70][71]

"Tardis" has also become a slang term used in the British real estate industry, to suggest that a house or apartment is actually substantally bigger on the inside that it looks on the outside.[72]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- Notes

- ^ The Doctor's TARDIS has its own name. In The Doctor's Wife (2011), the TARDIS's soul is placed into the body of a woman named Idris. When the Doctor asks Idris, "So what do I call you?" She replies, "I think you call me... Sexy."

- ^ The episode's writer Steven Moffat confirmed that this line was an in-joke aimed at fans on "Internet forums".[34]

- Citations

- ^ UK Trade Mark no. EU000333757 filed 25 July 1996; Classes 9, 16, 25, 28, and 41. See https://trademarks.ipo.gov.uk/ipo-tmcase/page/Results/4/EU000333757 .

- ^ "Case details for Trade Mark 1068700". UK Patent Office. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Pixley, Andrew; Morris, Jonathan; Atkinson, Richard; McGown; Hadoke, Toby (27 January 2016). "The Time Meddler: Production". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 5. Panini Magazines/Hachette Partworks Ltd. p. 134.

- ^ Pixley, Andrew; Morris, Jonathan; Atkinson, Richard; McGown, Alistair; Hadoke, Toby (10 February 2016). "Rose: Production". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 48. Panini Magazines/Hachette Partworks Ltd. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Pixley, Andrew; Morris, Jonathan; Atkinson, Richard; McGown, Alistair; Hadoke, Toby (10 February 2016). "Rose: Pre-production". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 48. Panini Magazines/Hachette Partworks Ltd. p. 37.

- ^ Burk & Smith 2012, p. 541.

- ^ "Article introducing Episode 1 of 'The Daleks' ("The Mutants"). From the Radio Times. Volume. 161. Issue No. 2093". The Doctor Who Cuttings Archive. 21–27 December 1963. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006.

- ^ a b Muir 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Haining 1995, p. 114.

- ^ a b Burk & Smith 2012, p. 542.

- ^ Phillips, Ivan (20 February 2020). Once Upon a Time Lord: The Myths and Stories of Doctor Who. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-78831-646-0. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Courtland; Smithka, Paula (22 October 2010). Doctor Who and Philosophy: Bigger on the Inside. Open Court. pp. 328–9. ISBN 978-0-8126-9725-4. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ a b "A Beginner's Guide to the TARDIS". BBC. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Halley, M., & Bowker, L. (2021). "Translation by TARDIS: The science of multilingual communication in Doctor Who". In L. Orthia & M. Harmes (eds.), Doctor Who and Science: Essays on Ideas, Identities and Ideology in the Series. McFarland. pp. 62–77

- ^ "The Time of Angels". Doctor Who. 24 April 2010. BBC.

- ^ "Journey's End (Doctor Who)". Doctor Who. 5 July 2008. BBC.

- ^ "The Satan Pit". Doctor Who. 10 June 2006. BBC.

- ^ Colgan, Jenny T (5 July 2012). Dark Horizons. BBC Books. ISBN 9781849904568.

- ^ "Wild Blue Yonder (Doctor Who)". Doctor Who. 2 December 2023. BBC.

- ^ Bythrow, Nick (12 December 2023). "Whether Ncuti Gatwa's TARDIS Remains The Same Ship Addressed By Doctor Who Showrunner". ScreenRant. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Howe; Walker (2003), p. 23

- ^ Meighan, Michael (15 October 2011). Glasgow with a Flourish. Amberley Publishing Limited. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-4456-1261-4.

- ^ Howe; Walker (2003), p. 15–16

- ^ "Doctor Who fan in tardis replica plan for Herne Bay". BBC. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "How Tall Is The Tardis? Tardis' Height". Colonel Height. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "The Doctor Who Transcripts – The Time Meddler". chakoteya.net. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Howe, David J.; Walker, Stephen James. "Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide: An Unearthly Child". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 March 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Robert W. (June 1994). "The Police Signal Box: A 100 Year History" (PDF). University of Strathclyde. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ "Doctor Who boss not worried by budget squeeze". BBC News. 23 March 2010.

- ^ a b Sibley, Anthony. "Doctor Who A History of the TARDIS Police Box Prop and its Modifications". www.themindrobber.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Brooks, Will (4 March 2020). "The Props". Medium. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Doctor Who A History of the TARDIS Police Box Prop and its Modifications". Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Scott, Cavan; Wright, Mark (7 June 2013). Doctor Who: Who-ology. Random House. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-1-4481-4125-8.

- ^ Pixley, Andrew; Morris, Jonathan; Atkinson, Richard; McGown, Alistair (23 March 2016). "Blink: Pre-production". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 56. Panini Magazines/Hachette Partworks Ltd. p. 57.

- ^ Tribe, Steve (2010). The Tardis Handbook. BBC Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84607-986-3. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Burk & Smith 2012, pp. 543–5.

- ^ Kistler, Alan (1 October 2013). Doctor Who: A History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4930-0016-6. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Interview: Doctor Who's Brian Hodgson on creating the sounds of the Tardis and Daleks". Radio Times. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Ness, Patrick (2013). Tip of the Tongue. London: Puffin Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-405-91213-6.

- ^ Butler, David, ed. (2007). Time and Relative Dissertations in Space: Critical Perspectives on Doctor Who. Manchester University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780719076824. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Are you a fan of Doctor Who? | Leonardo Hotels". www.leonardohotels.co.uk. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Burk & Smith 2012, p. 58.

- ^ "Doctor Who Tardis 4-Way USB Hub". Firebox.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- ^ "Miniature Tardis sells at auction". BBC News. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 19 April 2006.

- ^ "Case details for Trade Mark 2104259". UK Intellectual Property Office. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Knight, Mike. "In the matter of Application No. 2104259 by The British Broadcasting Corporation to register a series of three marks in Classes 9, 16, 25 and 41 and in the matter of Opposition thereto under No. 48452 by The Metropolitan Police Authority" (PDF). UK Patent Office. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "BBC wins police Tardis case". BBC News. 23 October 2002. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "'Sonic screwdriver' to be added to the Oxford English Dictionary". Radio Times.

- ^ Lomholt, Isabelle (18 October 2010). "Police Box Edinburgh: Scottish Tardis, Doctor Who". www.edinburgharchitecture.co.uk. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Dalziel, Magdalene (29 July 2017). "Dr Who Tardis-style cafe in Glasgow's Merchant City set to close". GlasgowLive. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "£10,500 to restore city 'Tardis'". BBC News. 22 January 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 3325 TARDIS (1984 JZ)" (4 June 2017 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Ferry, Ilan (10 May 2022). La Mythologie selon Le Seigneur des Anneaux (in French). Les Éditions de l'Opportun. p. 23. ISBN 978-2-38015-258-6. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Company Website, January 1, 2015". Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "TarDisk: MacBook Storage Expansion That's Bigger on the Inside". tech.co. 18 February 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ McKie, Robin (9 September 2023). "First cat in space: how a Parisian stray called Félicette was blasted far from Earth". The Observer – via The Guardian.

- ^ Ellis, Iain (30 June 2012). Brit Wits: A History of British Rock Humor. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-84150-671-5. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Radiohead – Up on the ladder lyrics". Genius Lyrics. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Caffrey, Dan (15 March 2021). Radiohead FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the World's Most Famous Cult Band. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4930-5397-1.

- ^ Searle, Adrian (16 February 2009). "Let's do the time warp again". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Jury, Louise (2 February 2009). "Reflective Doctor Who Tardis on show at Hayward Gallery". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Dominic Cavendish (2 July 2014). "The almost-definitive guide to Monty Python Live (Mostly)". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ "Monty Python's back, thanks to the 'retardis'". Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ "Doctor Who: the brief cameos that are definitely canon". Den of Geek. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "The Team Behind The Lego Movie 2 Describes What Went Into Those Surprising Cameos". Gizmodo. 11 February 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Kelly, James Floyd (15 July 2016). The Ultimate Player's Guide to LEGO Dimensions [Unofficial Guide]. Que Publishing. ISBN 978-0-13-446737-5. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Joseph Knoop (17 March 2022). "Fortnite gets Doctor Who's TARDIS and a bundle of themed modes". PC Gamer. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Scott, Danni (12 July 2023). "Doctor Who unveils pink Barbie Tardis in London". Metro. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Sorin (17 June 2013). "Doctor Who .. Happy Birthday coin for its 50th anniversary – Niue Island – TARDIS | Collectibles News". News.allnumis.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Tardis Environmental UK". Tardishire.co.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "The Who's Who of Commercial Loos – Profile: TARDIS Environmental" (PDF). Commercial Motor. 3 February 2022. p. 22. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Skinny House is considered to be 'London's coolest optical illusion' and looks much bigger inside". LADbible. 5 November 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

References

[edit]- Burk, Graeme; Smith, Robert (1 April 2012). Who Is the Doctor: The Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who: The New Series. ECW/ORIM. ISBN 978-1-77090-239-8. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- Haining, Peter (1995). Doctor Who, a celebration: two decades through time and space. London: Virgin. ISBN 9780863699320.

- Harris, Mark (1983). The Doctor Who Technical Manual. UK: Random House. ISBN 0-394-86214-7.

- Muir, John Kenneth (15 September 2015). A Critical History of Doctor Who on Television. McFarland. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-4766-0454-1.

- Nathan-Turner, John (1985). The TARDIS Inside Out. UK: Picadilly Press. ISBN 0-394-87415-3.

- Howe, David J.; Stephen James Walker (1994). The First Doctor Handbook. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 0-426-20430-1.

- Howe, David J.; Stephen James Walker (2003). The Television Companion: The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Doctor Who. Telos Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-903889-51-0.

- Howe, David J.; Arnold T. Blumberg (2003). Howe's Transcendental Toybox: The Unauthorised Guide to Doctor Who Collectibles. UK: Telos Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-903889-56-1.