Preselector

A preselector is a name for an electronic device that connects between a radio antenna and a radio receiver. The preselector is a band-pass filter that blocks troublesome out-of-tune frequencies from passing through from the antenna into the radio receiver (or preamplifier) that otherwise would be directly connected to the antenna.

Purpose

[edit]

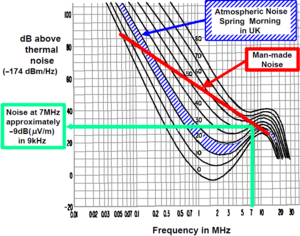

A preselector improves the performance of nearly any receiver, but is especially helpful[a] to receivers with broadband front-ends that are prone to overload, such as scanners, wideband software-defined radio receivers, ordinary consumer-market shortwave and AM broadcast receivers – particularly with receivers operating below 10~20 MHz where static is pervasive. Sometimes faint signals that occupy a very narrow frequency span (such as radiotelegraph or 'CW') can be heard more clearly if the receiving bandwidth is made narrower than the narrowest that a general-purpose receiver may be able to tune; likewise, signals which individually use a fairly wide span of frequencies, such as broadcast AM, can be made less noisy by narrowing the bandwidth of the signal, even though making the span of received frequencies narrower than was transmitted will sacrifice some audio fidelity. A good preselector often can reduce a radio's receive bandwidth to a narrower frequency span than many general-purpose radios can manage on their own.

A preselector typically is tuned to have a narrow bandwidth, centered on the receiver's operating frequency. The preselector passes through unchanged the signal on its tuned frequency (or only slightly diminished) but it reduces or removes off-frequency signals, cutting down or eliminating unwanted interference.[b]

Extra filtering can be useful because the first input stage ("front end") of receivers contains at least one RF amplifier, which has power limits ("dynamic range"). Most radios' front ends amplify all radio frequencies delivered to the antenna connection. So off-frequency signals constitute a load on the RF amplifier, wasting part of its dynamic range on unused and unwanted signals. "Limited dynamic range" means that the amplifier circuits have a limit to the total amount of incoming RF signal they can amplify without overloading; symptoms of overload are nonlinearity ("distortion") and ultimately clipping ("buzz").

When the front-end overloads the performance of the receiver is severely reduced, and in extreme cases can damage the receiver.[2] In situations with noisy and crowded bands, or where there is loud interference from nearby, high-power stations, the dynamic range of the receiver can quickly be exceeded. Extra filtering by the preselector limits frequency range and power demands that are applied to all later stages of the receiver, only loading it with signals within the preselected band.

Preselect filter bank

[edit]Similar to conventional radios, spectrum analyzers, heavy-duty network analyzers, and other RF measuring equipment can incorporate switchable banks of preselector circuits to reject out-of-band signals that could result in spurious signals at the frequencies being analyzed.[3] Automatically switched filter banks can likewise be incorporated into various broadband, general purpose receivers.

Multifunction preselectors

[edit]A preselector may be engineered with extra features, so that in addition to attenuating interference from unwanted frequencies it can provide additional services which may be helpful for a receiver:

- It can limit input signal voltage to protect a sensitive receiver from damage caused by static discharge, nearby voltage spikes, and overload from nearby transmitters' signals.

- It can provide a DC path to ground, to drain off noisy static charge that tends to collect on the antenna.

- It can also incorporate a small radio frequency amplifier stage to boost the filtered signal.

None of these extra conveniences are necessary for the function of preselection, and in particular, for the typical noisy frequency bands where a preselector is needed, an amplifier in the preselector has no useful function.

On the other hand, when an antenna preamplifier (preamp) is actually needed, it can be made "tunable" by incorporating a front-end preselector circuit to improve its performance. The integrated device is both a preamplifier and a preselector, and either name is correct. This ambiguity sometimes leads to confusion – conflating preselection with amplification.

Ordinary, regular preselectors (that are just preselectors) contain no amplifier: They are entirely passive devices. A standard, ordinary preselector sometimes has the word "passive" prefixed – hence "passive preselector" means "ordinary preselector". The adjective is redundant, but emphasizes to those only familiar with tunable preamplifiers that the preselector is normal, and has no internal amplifier, and requires no power supply. Since all ordinary preselectors are "passive", adding the redundant word is pedantic, and in the noisy longwave, mediumwave, and shortwave bands where preselectors are typically used, when used with "modern" (post 1950) receivers they function with no noticeable loss of signal strength.

Bandwidth vs. signal strength trade-off

[edit]With all preselectors there is some very small loss at the tuned frequency; usually, most of the loss is in the inductor (the tuning coil). Turning up the inductance gives the preselector a narrower bandwidth (or higher Q, or greater selectivity) and slightly raises the loss, which nonetheless remains very small.

Most preselectors have separate settings for one inductor and one capacitor (at least).[c] So with at least two adjustments available to tune to just one frequency, there are often a variety of possible settings that will tune the preselector to frequencies in its middle-range.

For the narrowest bandwidth (highest Q), the preselector is tuned using the highest inductance and lowest capacitance for the desired frequency, but this produces the greatest loss. It also requires retuning the preselector more often while searching for faint signals, to keep the preselector's pass band overlapping the radio's receiving frequency.

For lowest loss (and widest bandwidth), the preselector is tuned using the lowest inductance and highest capacitance (and the lowest Q, or least selectivity) for the desired frequency. The wider bandwidth allows more interference through from nearby frequencies, but reduces the need to retune the preselector while tuning the receiver, since any one low-inductance setting for the preselector will pass a broader span of nearby frequencies.

Different from an antenna tuner

[edit]Although a preselector is placed inbetween the radio and the antenna, in the same electrical location as a feedline matching unit, it serves a different purpose: A transmatch or "antenna" tuner connects two transmission lines with different impedances and only incidentally blocks out-of-tune frequencies (if it blocks any at all).

A transmatch matches transmitter impedance to feedline impedance and phase, so that signal power from the radio transmitter smoothly transfers into the antenna's feed cable; a properly adjusted transmatch prevents transmitted power from being reflected back into the transmitter ("backlash current"). Some antenna tuner circuits can both impedance match and preselect,[4] for example the Series Parallel Capacitor (SPC) tuner, and many 'tuned-transformer'-type matching circuits used in many balanced line tuners (BLT) can be adjusted to also function as band-pass filters.[d]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Despite being helpful for reducing off-frequency interference on relatively wideband antennas, such as dipoles and random wire antennas, a preselector provides little or no benefit to receivers or preamps when they are fed from a narrow-band source, such as a tuned small loop antenna.

- ^ Note that a preselector cannot remove any interference that comes through on the same frequency that it and the receiver are both tuned to.

- ^ The setting dials may be labeled as "BAND" (inductor, possibly also selection of a capacitor bank) and "TUNE" (capacitor, or extra capacitance for fine-tuning). Regardless of the labeling, if more than one setting of the two is possible for the same frequency, the settings' bandwidths will differ along with other properties like output and input impedances.

- ^ Some simpler types of antenna tuners that are not band-pass circuits can also provide limited preselection. The now-common C L C-type 'T'‑network is a high-pass circuit which always essentially eliminates frequencies below the operating frequency, but even when adjusted for greatest selectivity, cannot block higher frequencies nearly as well as a conventional preselector.[5] It can, however, be adjusted for high operating Q that might attenuate noise above the operating frequency by as much as 20 dB.[6] The complementary 'π'-network that was customarily incorporated in the final stage of 'vintage' tube transmitters and amplifiers is a low-pass circuit; it always essentially eliminates frequencies above the tuned frequency, and can be similarly adjusted to provide attenuation below the tuned frequency by as much as 20 dB.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Characteristics and Applications of Atmospheric Radio Noise Data (Report). International Radio Consultative Committee (CCIR). Geneva, CH: International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 1968. CCIR Report 322-3.; first CCIR Report 322 was 1963; revised first ed.; second is ISBN 92-61-01741-X.

- ^ Cutsogeorge, George (2014) [2009]. Managing Interstation Interference with Coaxial Stubs and Filters (2nd ed.). Aptos, CA: International Radio Corporation.

- ^ "A primer on RF filters for software-defined radio". Software-Defined Radio Simplified (blog). 24 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Stanley, John (K4ERO) (1999). "The filtuner". ARRL Antenna Compendium. Vol. 6. Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Griffith, Andrew S. (W4ULD) (January 1995). "Getting the most out of your 'T'‑network antenna tuner". QST Magazine Magazine. Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League. pp. 44–47. ISSN 0033-4812. OCLC 1623841.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stanley, John (K4ERO) (September 2015). "Antenna tuners as preselectors". Technical Correspondence. QST Magazine. Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League. p. 61.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- "Preselector design and construction". bobsamerica.com. Shortwave listening.