Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii

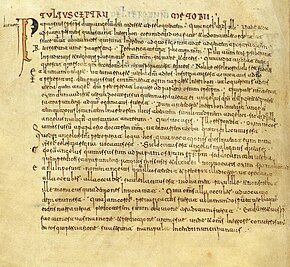

Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii is a short Latin biography of Muḥammad written in the 9th or 10th century in the Iberian Peninsula. It is a polemical text designed to show that Islam is a false religion and Muḥammad the unwitting dupe of the devil.[2] It is known from a single copy in the Codex of Roda.[3] Although the codex was compiled in the late 10th century, the Tultusceptru was added between about 1030 and 1060.[4]

Textual history

[edit]The Codex of Roda was copied in the late 10th or early 11th century in the Kingdom of Pamplona.[5] In the codex, the Tultusceptru comes immediately before the Chronica Prophetica. It belongs to a series of texts, including the Chronica, that Rodrigo Furtado groups together as the "Prophetic collection". Its purpose is thus to defend the prophecy in the Chronica that the Muslims would be expelled from Iberia.[6] The meaning of its title—"Tultusceptru from the Book of Lord Metobius"—is a mystery.[7][8] Tultusceptru may be a corruption of tultum excerptum, Latin for "extract taken from" (reading tultum as a form of tollo).[7][9] The Metobius of the title probably refers to the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, but there is nothing in that work that remotely corresponds to the Tultusceptru.[9]

Certain errors in the text suggest that the scribe who copied the Tultusceptru in the Codex of Roda had difficulty reading the text in front of him.[10] The text was probably originally written in Iberia, most likely in al-Andalus before being brought north to Asturias.[10][11] The author was evidently familiar with Islamic practice.[11]

Synopsis and analysis

[edit]According to the Tultusceptru, a Christian bishop named Osius was told by an angel to "go and speak to my satraps who dwell in Erribon," that is, Yathrib (Medina).[12] "But he was weak and was about to be summoned by the Lord."[13] Therefore, he sent a young monk named Ozim to take the message, but in Erribon he was met by an evil angel, who renamed him "Mohomad" and told him to tell the people of Erribon to recite the words Alla occuber alla occuber situ leila citus est Mohamet razulille. "And so", the account concludes, "what was to be a vessel of Christ became a vessel of Mammon to the perdition of [Ozim's] soul; and all those who converted to the error and all those who, through his persuasion, shall be, are numbered among the company of hell."[12]

The words the evil angel told Ozim to say are a somewhat garbled Latin rendering of the Arabic takbīr and shahāda, which both belong to the adhān (call to prayer).[2][12] The phrases Allāhu akbar (God is great), ashhadu anna lā ilāha (I witness that there is no god) and Muḥammad rasūl Allāh (Muḥammad is the messenger of God) are recognizable, but the cita est are not.[12] The name Ozim may be derived from Arabic ʿaẓīm (great)[12] or perhaps from the name of Muḥammad's clan, the Hāshim.[14]

In its basic outline, the Tultusceptru is a version of the eastern story of Bahira, the monk who discovered Muḥammad in various accounts, both Christian and Islamic. The name Bahira has been replaced by Osius, which is probably an allusion to the heretical Bishop Hosius of Corduba.[10] In the Tultusceptru, the bishop is orthodox, the angel that appears to him authentic and the intended message the true gospel. In the words of Kenneth Wolf, "the Tultusceptru is the tragic story of a pure revelation lost forever" that "stops well short of blaming Muḥammad for leading" the people of Medina to Hell.[15]

Influence

[edit]The Tultusceptru narrative re-appears in two 11th-century sources, Aimeric of Angoulême and Siguinus.[16][17] They record how a bishop named Osius sent a certain Ocin to bring a people the gospel only have him corrupted by a demon and renamed Muḥammad.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Furtado 2020, p. 65.

- ^ a b Tolan 2010.

- ^ Wolf 1990, p. 89.

- ^ Wolf 2014a, p. 17 n18.

- ^ Furtado 2020, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Furtado 2020, p. 55.

- ^ a b Wolf 2014a, p. 16 n15.

- ^ Yolles & Weiss 2018, p. x.

- ^ a b Vázquez de Parga 1971, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Christys 2002, p. 63.

- ^ a b Díaz y Díaz 1970, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Hoyland 1997, pp. 515–516.

- ^ Wolf 2014a, p. 17.

- ^ Wolf 2014a, p. 18.

- ^ Wolf 2014a, p. 19.

- ^ a b González Muñoz 2011.

- ^ Yolles & Weiss 2018, p. xxvi.

Bibliography

[edit]- Christys, Ann (2002). Christians in al-Andalus (711–1000). Routledge.

- Díaz y Díaz, Manuel C. (1970). "Los textos antimahometanos más antiguos en códices españoles". Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge. 37: 149–168. JSTOR 44514635.

- Furtado, Rodrigo (2020). "Emulating Neighbours in Medieval Iberia around 1000: A Codex from La Rioja (Madrid, RAH, cód. 78)". In Kim Bergqvist; Kurt Villads Jensen; Anthony John Lappin (eds.). Conflict and Collaboration in Medieval Iberia. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 43–72.

- González Muñoz, Fernando (2011). "Aimericus of Angoulême". In David Thomas; Alex Mallett; Juan Pedro Monferrer Sala; Johannes Pahlitzsch; Mark Swanson; Herman Teule; John Tolan (eds.). Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Vol. 3 (1050–1200). Leiden: Brill. pp. 204–207.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (1997). Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Darwin Press.

- Tieszen, Charles (2021). The Christian Encounter with Muhammad: How Theologians have Interpreted the Prophet. Bloomsbury.

- Tolan, John V. (2010). "Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii". In David Thomas; Alex Mallett (eds.). Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Vol. 2 (900–1050). Brill. pp. 83–84.

- Wolf, Kenneth Baxter (1990). "The Earliest Latin Lives of Muḥammad". In Michael Gervers; Ramzi Jibran Bikhazi (eds.). Conversion and Continuity: Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands, Eighth to Eighteenth Centuries. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 89–101.

- Wolf, Kenneth Baxter (2014). "Counterhistory in the Earliest Latin Lives of Muhammad". In Christiane J. Gruber; Avinoam Shalem (eds.). The Image of the Prophet between Ideal and Ideology: A Scholarly Investigation – The Image of the Prophet Between Ideal and Ideology. De Gruyter. pp. 13–26. doi:10.1515/9783110312546.13.

- Wolf, Kenneth Baxter (2014). "Falsifying the Prophet: Muhammad at the Hands of His Earliest Christian Biographers in the West". In Martijn Icks; Eric Shiraev (eds.). Character Assassination throughout the Ages. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 105–120. doi:10.1057/9781137344168_6.

- Vázquez de Parga, Luís (1971). "Algunas notas sobre el Pseudo Metodio y España". Habis. 2: 143–164.

- Yolles, Julian; Weiss, Jessica, eds. (2018). Medieval Latin Lives of Muhammad. Harvard University Press.