Bactria

| Bactria Balkh | |

|---|---|

| Province of the Achaemenid Empire, Seleucid Empire, and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom | |

| 2500/2000 BC–900/1000 AD | |

Approximate location of the region of Bactria  | |

| Capital | Bactra |

| Historical era | Antiquity |

• Established | 2500/2000 BC |

• Disestablished | 900/1000 AD |

| Today part of | Afghanistan Tajikistan Uzbekistan |

Bactria (/ˈbæktriə/; Bactrian: βαχλο, Bakhlo), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian[1] civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area within the north of modern Afghanistan. Bactria was strategically located south of Sogdia and the western part of the Pamir Mountains. The extensive mountain ranges acted as protective "walls" on three sides, with the Pamir on the north and the Hindu Kush on south forming a junction with the Karakoram range towards the east.

Called "beautiful Bactria, crowned with flags" by the Avesta, the region is considered, in the Zoroastrian faith, to be one of the "sixteen perfect Iranian lands" that the supreme deity, Ahura Mazda, had created. It was once a small and independent kingdom struggling to exist against nomadic Turanians.[2] One of the early centres of Zoroastrianism, and capital of the legendary Kayanian dynasty, Bactria is mentioned in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great as one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire; it was a special satrapy, ruled by a crown prince or an intended heir.[1] Bactria was the centre of Iranian resistance against the Greek Macedonian invaders after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC, but eventually fell to Alexander the Great. After the death of Alexander, Bactria was annexed by his general, Seleucus I.[3]

The Seleucids lost the region after the declaration of independence by the satrap of Bactria, Diodotus I; thus began the history of the Greco-Bactrian, and later the Indo-Greek, Kingdoms. By the second century BC, Bactria was conquered by the Parthian Empire, and, in the early first century, the Kushan Empire was formed by the Yuezhi within Bactrian territories. Shapur I, the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran, conquered western parts of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century, and the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom was formed. The Sasanians lost Bactria in the 4th century, but reconquered it in the 6th century. Bactrian (natively known as ariao, 'Iranian'),[4] an Eastern Iranian language, was the common language of Bactria and surroundings areas in ancient and early medieval times.

The Islamization of Bactria began with the Muslim conquest of Iran in the 7th century. The capital city of Bactra was centre of an Iranian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries,[5] and New Persian as an independent literary language first emerged in this region. The Samanid Empire was formed in Eastern Iran by the descendants of Saman Khuda, a Persian from Bactria, beginning the spread of the Persian language in the region and the decline of the Bactrian language.

Etymology

[edit]

The modern English name of the region is Bactria. Historically, the region was first mentioned in Avestan as Bakhdi in Old Persian. This later developed into Bāxtriš in Middle Persian and Baxl in New Persian.[6] The modern name is derived from the Ancient Greek: Βακτριανή (Romanized Greek term: Baktrianē), which is the Hellenized version of the Bactrian endonym. Other cognates include βαχλο (Romanized: Bakhlo). بلخ (Romanized: Balx), Chinese 大夏 (pinyin: Dàxià), Latin Bactriana. The region was mentioned in ancient Sanskrit texts as बाह्लीक or Bāhlīka.

Wilhelm Eilers proposed that the region was named after the Balkh River (in Greek transliteration Βάκτρος) from underlying Bāxtri-, itself meaning 'she who divides', from the Proto-Indo-European root *bhag- 'to divide' (whence also Avestan bag- and Old Indic bháj-).[7]

Bactria is the geographic location Bactrian camels are named after.

Geography

[edit]The Bactrian plain lay between the Amu Darya (ancient Oxus River) to the north and the Hindu Kush mountain range to the south and east.[8] On its western side, the region was bordered by the great Carmanian desert and the plain of Margiana. The Amu Darya and smaller rivers such as (from west to east) the Shirin Tagab River, Sari Pul River, Balkh River and Kunduz River have been used for irrigation for millennia. The land was noted for its fertility and its ability to produce most ancient Greek agricultural products, with the notable exception of olives.[9]

According to Pierre Leriche:

Bactria, the territory of which Bactra was the capital, originally consisted of the area south of the Āmū Daryā with its string of agricultural oases dependent on water taken from the rivers of Balḵ (Bactra), Tashkurgan, Kondūz, Sar-e Pol, and Šīrīn Tagāō. This region played a major role in Central Asian history. At certain times the political limits of Bactria stretched far beyond the geographic frame of the Bactrian plain.[10]

History

[edit]Bronze Age

[edit]Right: Ancient bowl with animals, Bactria, 3rd–2nd millennium BC.

The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC, also known as the "Oxus civilization") is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age archaeological culture of Central Asia, dated to c. 2200–1700 BC, located in present-day eastern Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (known to the ancient Greeks as the Oxus River), an area covering ancient Bactria. Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for Old Persian Bāxtriš (from native *Bāxçiš)[13] (named for its capital Bactra, modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Margu, the capital of which was Merv, in today's Turkmenistan.

The early Greek historian Ctesias, c. 400 BC (followed by Diodorus Siculus), alleged that the legendary Assyrian king Ninus had defeated a Bactrian king named Oxyartes in c. 2140 BC, or some 1000 years before the Trojan War. Since the decipherment of cuneiform script in the 19th century, however, which enabled actual Assyrian records to be read, historians have ascribed little value to the Greek account.

According to some writers, [who?] Bactria was the homeland (Airyanem Vaejah) of Indo-Iranians who moved south-west into Iran and the north-west of the South Asian subcontinent around 2500–2000 BC. Later, it became the northern province of the Achaemenid Empire in Central Asia.[14] It was in these regions, where the fertile soil of the mountainous country is surrounded by the Turan Depression, that the prophet Zoroaster was said to have been born and gained his first adherents. Avestan, the language of the oldest portions of the Zoroastrian Avesta, was one of the Old Iranian languages, and is the oldest attested member of the Eastern Iranian languages.

Achaemenid Empire

[edit]

Ernst Herzfeld suggested that Bactria belonged to the Medes[15] before its annexation to the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great in sixth century BC, after which it and Margiana formed the twelfth satrapy of Persia.[16] After Darius III had been defeated by Alexander the Great, the satrap of Bactria, Bessus, attempted to organize a national resistance but was captured by other warlords and delivered to Alexander. He was then tortured and killed.[17][18]

Under Persian rule, many Greeks were deported to Bactria, so that their communities and language became common in the area. During the reign of Darius I, the inhabitants of the Greek city of Barca, in Cyrenaica, were deported to Bactria for refusing to surrender assassins.[19] In addition, Xerxes also settled the "Branchidae" in Bactria; they were the descendants of Greek priests who had once lived near Didyma (western Asia Minor) and betrayed the temple to him.[20] Herodotus also records a Persian commander threatening to enslave daughters of the revolting Ionians and send them to Bactria.[21] Persia subsequently conscripted Greek men from these settlements in Bactria into their military, as did Alexander later.[22]

Alexander The Great

[edit]

Alexander conquered Sogdiana. In the south, beyond the Oxus, he met strong resistance, but ultimately conquered the region through both military force and diplomacy, marrying Roxana, daughter of the defeated Satrap of Bactria, Oxyartes. He founded two Greek cities in Bactria, including his easternmost, Alexandria Eschate (Alexandria the Furthest).

After Alexander's death, Diodorus Siculus tells us that Philip received dominion over Bactria, but Justin names Amyntas to that role. At the Treaty of Triparadisus, both Diodorus Siculus and Arrian agree that the satrap Stasanor gained control over Bactria. Eventually, Alexander's empire was divided up among the generals in Alexander's army. Bactria became a part of the Seleucid Empire, named after its founder, Seleucus I.

Seleucid Empire

[edit]The Macedonians, especially Seleucus I and his son Antiochus I, established the Seleucid Empire and founded a number of Greek towns. The Greek language became dominant for some time there.

The paradox that Greek presence was more prominent in Bactria than in areas far closer to Greece can possibly be explained by past deportations of Greeks to Bactria.[23] When Alexander's troops entered Bactria they discovered communities of Greeks who appeared to have been deported to the region by the Persians in previous centuries.

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

[edit]

Considerable difficulties faced by the Seleucid kings and the attacks of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus gave the satrap of Bactria, Diodotus I, the opportunity to declare independence about 245 BC and conquer Sogdia. He was the founder of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Diodotus and his successors were able to maintain themselves against the attacks of the Seleucids—particularly from Antiochus III the Great, who was ultimately defeated by the Romans (190 BC).

The Greco-Bactrians were so powerful that they were able to expand their territory as far as South Asia:

As for Bactria, a part of it lies alongside Aria towards the north, though most of it lies above Aria and to the east of it. And much of it produces everything except oil. The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Bactria and beyond, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander...."[24]

The last Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles I lost control of Bactria to nomadic invaders near the end of the 2nd century BC, at which point Greek political power ceased in Bactria, but Greek cultural influence continued for many more centuries.[25] The Greco-Bactrians used the Greek language for administrative purposes, and the local Bactrian language was also Hellenized, as suggested by its adoption of the Greek alphabet and Greek loanwords.[26]

Indo-Greek Kingdom

[edit]

The Bactrian king Euthydemus I and his son Demetrius I crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and began the conquest of the Indus valley. For a short time, they wielded great power: a great Greek empire seemed to have arisen far in the East. But this empire was torn by internal dissension and continual usurpations. When Demetrius advanced far east of the Indus River, one of his generals, Eucratides, made himself king of Bactria, and soon in every province there arose new usurpers, who proclaimed themselves kings and fought against each other. For example Eucratides is known to have battled another king named Demetrius of India, probably Demetrius II, the latter ultimately being defeated according to the historian Justin.[27]

Most of them we know only by their coins, a great many of which are found in Afghanistan. By these wars, the dominant position of the Greeks was undermined even more quickly than would otherwise have been the case. After Demetrius and Eucratides, the kings abandoned the Attic standard of coinage and introduced a native standard, no doubt to gain support from outside the Greek minority.

In the Indus valley, this went even further. The Indo-Greek king Menander I (known as Milinda in South Asia), recognized as a great conqueror, converted to Buddhism. His successors managed to cling to power until the last known Indo-Greek ruler, a king named Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 55 BC.[28] Other sources, however, place the end of Strato II's reign as late as 10 AD.

Daxia, Tukhara and Tokharistan

[edit]Daxia, Ta-Hsia, or Ta-Hia (Chinese: 大夏; pinyin: Dàxià) was the name given in antiquity by the Han Chinese to Tukhara or Tokhara:[citation needed] the central part of Bactria. The name "Daxia" appears in Chinese from the 3rd century BC to designate a little-known kingdom located somewhere west of China. This was possibly a consequence of the first contacts between China and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.

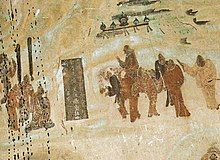

During the 2nd century BC, the Greco-Bactrians were conquered by nomadic Indo-European tribes from the north, beginning with the Sakas (160 BC). The Sakas were overthrown in turn by the Da Yuezhi ("Greater Yuezhi") during subsequent decades. The Yuezhi had conquered Bactria by the time of the visit of the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian (circa 127 BC), who had been sent by the Han emperor to investigate lands to the west of China.[29][30] The first mention of these events in European literature appeared in the 1st century BC, when Strabo described how "the Asii, Pasiani, Tokhari, and Sakarauli" had taken part in the "destruction of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom".[31] Ptolemy subsequently mentioned the central role of the Tokhari among other tribes in Bactria. As Tukhara or Tokhara it included areas that were later part of Surxondaryo Region in Uzbekistan, southern Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan. The Tokhari spoke a language known later as Bactrian – an Iranian language. (The Tokhari and their language should not be confused with the Tocharian people who lived in the Tarim Basin between the 3rd and 9th centuries AD, or the Tocharian languages that form another branch of Indo-European languages.)

The name Daxia was used in the Shiji ("Records of the Grand Historian") by Sima Qian. Based on the reports of Zhang Qian, the Shiji describe Daxia as an important urban civilization of about one million people, living in walled cities under small city kings or magistrates. Daxia was an affluent country with rich markets, trading in an incredible variety of objects, coming from as far as Southern China. By the time Zhang Qian visited, there was no longer a major king, and the Bactrians were under the suzerainty of the Yuezhi. Zhang Qian depicted a rather sophisticated but demoralised people who were afraid of war. Following these reports, the Chinese emperor Wu Di was informed of the level of sophistication of the urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, and became interested in developing commercial relationship with them:

The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Dayuan and the possessions of Daxia and Anxi Parthia are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the people of Han, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China.[32]

These contacts immediately led to the dispatch of multiple embassies from the Chinese, which helped to develop trade along the Silk Roads.

Kujula Kadphises, the xihou (prince) of the Yuezhi, united the region in the early 1st century and laid the foundations for the powerful, but short-lived, Kushan Empire. In the 3rd century AD, Tukhara was under the rule of the Kushanshas (Indo-Sasanians).

Tokharistan

[edit]The form Tokharistan – the suffix -stan means "place of" in Persian – appeared for the first time in the 4th century, in Buddhist texts, such as the Vibhasa-sastra. Tokhara was known in Chinese sources as Tuhuluo (吐呼羅) which is first mentioned during the Northern Wei era. In the Tang dynasty, the name is transcribed as Tuhuoluo (土豁羅). Other Chinese names are Doushaluo 兜沙羅, Douquluo 兜佉羅 or Duhuoluo 覩貨羅.[citation needed] During the 5th century AD, Bactria was controlled by the Xionites and the Hephthalites, but was subsequently reconquered by the Sassanid Empire.

Introduction of Islam

[edit]By the mid-7th century AD, Islam under the Rashidun Caliphate had come to rule much of the Middle East and western areas of Central Asia.[34]

In 663 AD, the Umayyad Caliphate attacked the Buddhist Shahi dynasty ruling in Tokharistan. The Umayyad forces captured the area around Balkh, including the Buddhist monastery at Nava Vihara, causing the Shahis to retreat to the Kabul Valley.[34]

In the 8th century AD, a Persian from Balkh known as Saman Khuda left Zoroastrianism for Islam while living under the Umayyads. His children founded the Samanid Empire (875–999 AD). Persian became the official language and had a higher status than Bactrian, because it was the language of Muslim rulers. It eventually replaced the latter as the common language due to the preferential treatment as well as colonization.[35]

Bactrian people

[edit]

Several important trade routes from India and China (including the Silk Road) passed through Bactria and, as early as the Bronze Age, this had allowed the accumulation of vast amounts of wealth by the mostly nomadic population. The first proto-urban civilization in the area arose during the 2nd millennium BC.

Control of these lucrative trade routes, however, attracted foreign interest, and in the 6th century BC the Bactrians were conquered by the Persians, and in the 4th century BC by Alexander the Great. These conquests marked the end of Bactrian independence. From around 304 BC the area formed part of the Seleucid Empire, and from around 250 BC it was the centre of a Greco-Bactrian kingdom, ruled by the descendants of Greeks who had settled there following the conquest of Alexander the Great.

The Greco-Bactrians, also known in Sanskrit as Yavanas, worked in cooperation with the native Bactrian aristocracy. By the early 2nd century BC the Greco-Bactrians had created an impressive empire that stretched southwards to include north-west India. By about 135 BC, however, this kingdom had been overrun by invading Yuezhi tribes, an invasion that later brought about the rise of the powerful Kushan Empire.

Bactrians were recorded in Strabo's Geography: "Now in early times the Sogdians and Bactrians did not differ much from the nomads in their modes of life and customs, although the Bactrians were a little more civilised; however, of these, as of the others, Onesicritus does not report their best traits, saying, for instance, that those who have become helpless because of old age or sickness are thrown out alive as prey to dogs kept expressly for this purpose, which in their native tongue are called "undertakers," and that while the land outside the walls of the metropolis of the Bactrians looks clean, yet most of the land inside the walls is full of human bones; but that Alexander broke up the custom."[37]

The Bactrians spoke Bactrian, a north-eastern Iranian language. Bactrian became extinct, replaced by north-eastern[38] Iranian languages such as Munji, Yidgha, Ishkashimi, and Pashto. The Encyclopaedia Iranica states:

Bactrian thus occupies an intermediary position between Pashto and Yidgha-Munji on the one hand, Sogdian, Choresmian, and Parthian on the other: it is thus in its natural and rightful place in Bactria.[39]

The principal religions of the area before the Islamic invasion were Zoroastrianism and Buddhism.[40] Contemporary Tajiks are the descendants of ancient Eastern Iranian inhabitants of Central Asia, in particular, the Sogdians and the Bactrians, and possibly other groups, with an admixture of Western Iranian Persians and non-Iranian peoples.[41][42][43] The Encyclopædia Britannica states:

The Tajiks are the direct descendants of the Iranian peoples whose continuous presence in Central Asia and northern Afghanistan is attested from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. The ancestors of the Tajiks constituted the core of the ancient population of Khwārezm (Khorezm) and Bactria, which formed part of Transoxania (Sogdiana). They were included in the empires of Persia and Alexander the Great, and they intermingled with such later invaders as the Kushāns and Hepthalites in the 1st–6th centuries AD. Over the course of time, the eastern Iranian dialect that was used by the ancient Tajiks eventually gave way to Persian, a western dialect spoken in Iran and Afghanistan.[44]

In popular culture

[edit]- The six-part documentary Alexander's Lost World explores the possible sites of Bactrian cities that historians believe were founded by Alexander the Great, including Alexandria on the Oxus. The series also explores the pre-existing Oxus civilization.[45]

- The site was portrayed in the 2004 film Alexander where Darius III was found dying.

See also

[edit]- History of Afghanistan

- History of Uzbekistan

- Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex

- Bactrian camel

- Bactrosaurus

- Bahlikas

- Dalverzin Tepe

- Greater Khorasan

- Tillya Tepe

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Saydali Mukhidinov (2018). "Ancestral Home of Indo-Aryan Peoples and Migration of Iranian Tribes to Southeastern Europe". SHS Web of Conferences. 50: 01237. doi:10.1051/shsconf/20185001237. S2CID 165176167.

- ^ J. K. (July 1913). "Bactria: the History of a Forgotten Empire. By H. G. Rawlinson, M.A., I.E.S. Probsthain's Oriental Series". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 45 (3): 733–735. doi:10.1017/s0035869x00045470. ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ Yusupovich, Kushokov Safarali (2020-10-28). "The Emergence Of Religious Views Is Exemplified By The Southern Regions". The American Journal of Social Science and Education Innovations. 02 (10): 143–145. doi:10.37547/tajssei/volume02issue10-22. ISSN 2689-100X.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- ^ Asiatic Papers. Bactra Retrieved 11 March 2023

- ^ Eduljee, Ed. "Aryan Homeland, Airyana Vaeja, in the Avesta. Aryan lands and Zoroastrianism". www.heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ Tavernier, Jan (2007). Iranica in the Achaemenid Period (ca. 550–330 B.C.): Lexicon of Old Iranian Proper Names and Loanwords, Attested in Non-Iranian Texts. Peeters. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-429-1833-7.

- ^ Higham, Charles F. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Facts On File, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 0-8160-4640-9.

- ^ Rawlinson, H. G. (1912). Bactria: The History of a Forgotten Empire. London: Probstain & co.

- ^ P. Leriche, "Bactria, Pre-Islamic period", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 3, 1998.

- ^ Inagaki, Hajime. Galleries and Works of the MIHO MUSEUM. Miho Museum. p. 45.

- ^ Tarzi, Zémaryalaï (2009). "Les représentations portraitistes des donateurs laïcs dans l'imagerie bouddhique". KTEMA. 34 (1): 290. doi:10.3406/ktema.2009.1754.

- ^ David Testen, "Old Persian and Avestan Phonology", Phonologies of Asia and Africa, vol. II (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 583.

- ^ Cotterell (1998), p. 59

- ^ Herzfeld, Ernst (1968). The Persian Empire: Studies in geography and ethnography of the ancient Near East. F. Steiner. p. 344.

- ^ "BACTRIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

After annexation to the Persian empire by Cyrus in the sixth century, Bactria together with Margiana formed the Twelfth Satrapy.

- ^ Holt (2005), pp. 41–43.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Herodotus, 4.200–204

- ^ Strabo, 11.11.4

- ^ Herodotus 6.9

- ^ "Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom". www.cemml.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-12-23. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Walbank, 30

- ^ Strabo "Geography, Book 11, chapter 11, section 1".

- ^ Jakobsson, Jens. "The Greeks of Afghanistan Revisited." Nomismatika Khronika (2007): page 17.

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile: Pashto Archived 2009-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Justin on Demetrius: "Multa tamen Eucratides bella magna uirtute gessit, quibus adtritus cum obsidionem Demetrii, regis Indorum, pateretur, cum CCC militibus LX milia hostium adsiduis eruptionibus uicit. Quinto itaque mense liberatus Indiam in potestatem redegit." Justin XLI,6[usurped]

- ^ Bernard (1994), p. 126.

- ^ Silk Road, North China C. Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, 19 November 2007, ed. Andy Burnham

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Strabo, 1.8.2

- ^ Hanshu, Former Han History

- ^ a b Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition

- ^ a b History of Buddhism in Afghanistan by Dr. Alexander Berzin, Study Buddhism

- ^ "Origin of the Samanids – Kamoliddin – Transoxiana 10". www.transoxiana.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ LITVINSKII, B. A.; PICHIKIAN, I. R. (1994). "The Hellenistic Architecture and Art of the Temple of the Oxus" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 47–66. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24048765.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book XI Chapter 11". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ "The Modern Eastern Iranian languages are even more numerous and varied. Most of them are classified as North-Eastern: Ossetic; Yaghnobi (which derives from a dialect closely related to Sogdian); the Shughni group (Shughni, Roshani, Khufi, Bartangi, Roshorvi, Sarikoli), with which Yaz-1ghulami (Sokolova 1967) and the now extinct Wanji (J. Payne in Schmitt, p. 420) are closely linked; Ishkashmi, Sanglichi, and Zebaki; Wakhi; Munji and Yidgha; and Pashto.

- ^ N. Sims-Williams. "Bactrian language". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Originally Published: December 15, 1988.

- ^ John Haywood and Simon Hall (2005). Peoples, nations and cultures. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan : country studies Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, page 206

- ^ Richard Foltz, A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, London: Bloomsbury, 2019, pp. 33-61.

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye, "Persien: bis zum Einbruch des Islam" (original English title: "The Heritage Of Persia"), German version, tr. by Paul Baudisch, Kindler Verlag AG, Zürich 1964, pp. 485–498

- ^ "Tajikistan: History". 28 August 2023. Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ "David Adams Films". Alexander's Lost World

Sources

[edit]- Bernard, Paul (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, pp. 99–129. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Beal, Samuel (trans.). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. Two volumes. London. 1884. Reprint: Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, 1969. Several editions online at Archive.Org

- Beal, Samuel (trans.). The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. London, 1911. Reprint: New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1973.

- Cotterell, Arthur. From Aristotle to Zoroaster, 1998; pages 57–59. ISBN 0-684-85596-8.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." Second Draft Edition.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD. Draft annotated English translation.

- Holt, Frank Lee. (1999). Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bactria. Berkeley: University of California Press.(hardcover, ISBN 0-520-21140-5).

- Holt, Frank Lee. (2005). Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24553-9.

- Omar, Coloru (2009). Da Alessandro a Menandro. Il regno greco di Battriana. Pisa/Roma: Fabrizio Serra.

- Posch, Walter (1995). Baktrien zwischen Griechen und Kuschan. Untersuchungen zu kulturellen und historischen Problemen einer Übergangsphase. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, ISBN 3-447-03701-6

- Waghmar, Burzine. (2020). "Between Hind and Hellas: the Bactrian Bridgehead (with an appendix on Indo-Hellenic interactions)". In: Indo-Hellenic Cultural Transactions. (2020). Edited by Radhika Seshan. Mumbai: K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, 2020 [2021], pp. 187–228. ISBN 978-938-132418-9, (paperback).

- Tremblay, Xavier (2007) "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia ― Buddhism among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th century." Xavier Tremblay. In: The Spread of Buddhism. (2007). Edited by Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacher. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section Eight, Central Asia. Edited by Denis Sinor and Nicola Di Cosmo. Brill, Lieden; Boston. pp. 75–129.

- Watson, Burton (trans.). "Chapter 123: The Account of Dayuan." Translated from the Shiji by Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian of China II (Revised Edition). Columbia University Press, 1993, pages 231–252. ISBN 0-231-08164-2 (hardback), ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (paperback).

- Watters, Thomas. On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India (A.D. 629–645). Reprint: New Delhi: Mushiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1973. Online at Archive.Org

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–181.

- Walbank, F.W. (1981). "The Hellenistic World". Fontana Press. ISBN 0-006-86104-0.

External links

[edit]- Livius.org: Bactria

- Bactrian Coins

- Bactrian Gold

- Art of the Bronze Age: Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Bactria

- Bactria

- States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 10th century

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- Buddhism in Iran

- Historical regions

- Historical regions of Afghanistan

- Historical regions of Iran

- History of Central Asia

- History of South Asia

- 1000 disestablishments