Name of Mexico

Several hypotheses seek to explain the etymology of the name Mexico (México in modern Spanish) which dates, at least, back to 14th century Mesoamerica. Among these are expressions in the Nahuatl language such as, "Place in the middle of the century plant" (Mexitli) and "Place in the Navel of the Moon" (Mēxihco) along with the currently used shortened form in Spanish, "belly button of the moon" ("el ombligo de la luna"), used in both 21st century speech and literature. Presently, there is still no consensus among experts.[1]

As far back as 1590, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum showed that the northern part of the New World was known as "America Mexicana" (Mexican America), as Mexico City was the seat for the New Spain viceroyalty. New Spain was not the old name for Mexico, but was in actuality the name of all Spanish colonial possessions in North America, the Caribbean, and The Philippines; since New Spain was not actually a state or a contiguous piece of land, in modern times, "Mexico" would have been a jurisdiction under the command of the authorities in modern Mexico City. Under the Spaniards, Mexico was both the name of the capital and its sphere of influence, most of which exists as Greater Mexico City and the State of Mexico. Some parts of Puebla, Morelos and Hidalgo were also part of Spanish-era Mexico.

In 1821, the continental part of New Spain seceded from Spain during the Trienio Liberal, in which Agustin de Iturbide marched triumphantly with his Army of the Three Guarantees (religion, independence, and unity). This was followed by the birth of the short-lived First Mexican Empire that used the "Mexico" name according to the convention used previously by the Roman Empire (Latin: Imperium Romanum) and the Holy Roman Empire, whereby the capital gives rise to the name of the Empire. This was the first recorded use of "Mexico" as a country title.

After the Empire fell and the Republic was established in 1824, a Federation name form was adopted; which was, at most times, more de jure than de facto. The Mexican name stuck, leading to the formation of the Mexican Republic which formally is known as the United Mexican States.

Complications arose with the capital's former colloquial and semi-official name "Ciudad de Mexico, Distrito Federal (Mexico, D.F.)", which appeared on postal addresses and was frequently cited in the media, thus creating a duplication whereas the shortened name was "Mexico, D.F., Mexico". Legally, the name was Distrito Federal (Federal District or District of the Federation). This ended with the change in status of Mexico City in 2016. Today it is officially called "Ciudad de México, México" abbreviated CDMX, Mexico.

The official name of the country is the "United Mexican States" (Spanish: Estados Unidos Mexicanos), since it is a federation of thirty-two states. The official name was first used in the Constitution of 1824, and was retained in the constitutions of 1857 and 1917. Informally, "Mexico" is used along with "Mexican Republic" (República Mexicana). On 22 November 2012, outgoing Mexican President Felipe Calderón proposed changing the official name of the country to México.[2]

Names of the country

[edit]

Anahuac (meaning land surrounded by water) was the name in Nahuatl given to what is now Mexico during Pre-colonial times. When the Spanish conquistadors besieged México-Tenochtitlan in 1521, it was almost completely destroyed. It was rebuilt during the following three years, after which it was designated as a municipality and capital of the vice-royalty of New Spain. In 1524 the municipality of Mexico City was established, known as México Tenustitlan, and as of 1585 became officially known simply as Ciudad de México.[3] The name Mexico was used only to refer to the city, and later to a province within New Spain. It was not until the independence of the vice-royalty of New Spain that "Mexico" became the traditional short-form name of the country.

During the 1810s, different insurgent groups advocated and fought for the independence of the vice-royalty of New Spain. This vast territory was composed of different intendencias and provinces, successors of the kingdoms and captaincies general administered by the vice-regal capital of Mexico City. In 1813, the deputies of the Congress of Anahuac signed the document Acta Solemne de la Declaración de Independencia de la América Septentrional, ("Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America"). In 1814 the Supreme Congress of the revolutionary forces that met at Apatzingán (in today's state of Michoacán) drafted the first constitution,[4] in 1814 whereby the name América Mexicana ("Mexican America") was chosen for the country. The head of the insurgent forces, however, was defeated by the royalist forces, and the constitution was never enacted.

Servando Teresa de Mier, in a treatise written in 1820 in which he discussed the reasons why New Spain was the only overseas territory of Spain that had not yet secured its independence, chose the term Anáhuac to refer to the country.[5] This term, in Nahuatl, was used by the Mexica to refer to the territory they dominated. According to some linguists, it means "near or surrounded by waters", probably about Lake Texcoco,[6] even though it was also the word used to refer to the world or the terrestrial universe (as when used in the phrase Cem Anáhuac, "the entire earth") and in which their capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was at the centre and at the same time at the centre of the waters, being built on an island in a lake.[7]

In September 1821, the independence of Mexico was finally recognized by Spain, achieved through an alliance of royalist and revolutionary forces. The former tried to preserve the status quo of the vice-royalty, menaced by the liberal reforms taking place in Spain, through the establishment of an autonomous constitutional monarchy under an independence hero. Agustín was crowned and given the titles of: Agustin de Iturbide por la divina providencia y por el Congreso de la Nación, primer Emperador Constitucional de Mexico (Agustín de Iurbide First Constitutional Emperor of Mexico by Divine Providence and by the Congress of the Nation). The name chosen for the country was Imperio Mexicano, "Mexican Empire". The empire collapsed in 1823, and the republican forces drafted a constitution the following year whereby a federal form of government was instituted. In the 1824 constitution, which gave rise to the Mexican federation, Estados Unidos Mexicanos (also Estados-unidos mexicanos)—literally the Mexican United States or Mexican United-States (official English translation: United Mexican States)—was adopted as the country's official name.[8][9] The constitution of 1857 used the term República Mexicana (Mexican Republic) interchangeably with Estados Unidos Mexicanos;[10] the current constitution, promulgated in 1917, only uses the latter[11] and United

Mexican States is the normative English translation.[12] The name "Mexican Empire" was briefly revived from 1863 to 1867 by the conservative government that instituted a constitutional monarchy for a second time under Maximilian of Habsburg.

On 22 November 2012, incumbent President Felipe Calderón sent to the Mexican Congress a piece of legislation to change the country's name officially to simply Mexico. To go into effect, the bill would have to be passed by both houses of Congress, as well as a majority of Mexico's 31 state legislatures. Coming within just a week before Calderón turned power over to then president elect Enrique Peña Nieto, many of the president's critics saw the proposal as nothing more than a symbolic gesture.[13]

Etymology

[edit]According to one legend,[14] the war deity and patron of the Mexica Huitzilopochtli possessed Mexitl or Mexi as a secret name. Mexico would then mean "Place of Mexi" or "Land of the War God."

Another hypothesis[15] suggests that Mēxihco derives from a portmanteau of the Nahuatl words for "moon" (mētztli) and navel (xīctli). This meaning ("Place at the Center of the Moon") might then refer to Tenochtitlan's position in the middle of Lake Texcoco. The system of interconnected lakes, of which Texcoco formed the center, had the form of a rabbit, which the Mesoamericans pareidolically associated with the moon.

Still another hypothesis[15] offers that it is derived from Mectli, the goddess of maguey.

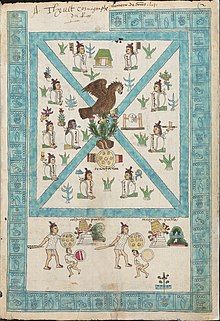

These last two suggestions are deprecated by linguist Frances Karttunen,[16] since the final form "Mēxihco" differs in vowel length from both proposed elements. Nahua toponymy is full of mysticism, however, as it was pointed out by the Spanish missionary Bernardino de Sahagún. In his mystic interpretation, Mexico could mean "Center of the World," and, in fact, it was represented as such in various codices, as a place where all water currents that cross the Anahuac ("world" or "land surrounded by seas") converge (see image on the Mendoza codex). It is thus possible that the other meanings (or even the "secret name" Mexi) were then popular pseudoetymologies.

Mexico and Mexica

[edit]The name Mexico has been commonly described to be a derivative from Mexica, the autonym of the Aztec people,[17] but said affirmation is controversial as there are many competing etymologies for both terms[18] and given the fact that in many old sources, 'Mexica' simply appears as the way to call the inhabitants of the island of Mexico (where Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco were located) in their native Nahuatl;[19] implying that instead of Mexica being the source of the name 'Mexico', the opposite would be true.[20]

Phonetic evolution

[edit]The Nahuatl word Mēxihco (Nahuatl pronunciation: [meːˈʃiʔko] ⓘ) was transliterated as "México" using Medieval Spanish orthography, in which the x represented the voiceless postalveolar fricative ([ʃ], the equivalent of English sh in "shop"), making "México" pronounced as [ˈmeʃiko]. At the time, Spanish j represented the voiced postalveolar fricative ([ʒ], like the English s in "vision", or French j today). However, by the end of the fifteenth century j had evolved into a voiceless palato-alveolar sibilant as well, and thus both x and j represented the same sound ([ʃ]). During the sixteenth century this sound evolved into a voiceless velar fricative ([x], like the ch in Scottish "loch"), and México began to be pronounced [ˈmexiko].[21]

Given that both x and j represented the same new sound (/x/), and in lack of a spelling convention, many words that originally had the /ʃ/ sound, began to be written with j (e.g. it wasn't uncommon to find both exército and ejército used during the same time period, even though that due to historicity, the correct spelling would have been exército). The Real Academia Española, the institution in charge of regulating the Spanish language, was established in 1713, and its members agreed to simplify spelling, and set j to represent /x/ regardless of the original spelling of the word, and x to represent /ks/. (The ph spelling underwent a similar removal, in that it was simplified as f in all words, e.g. philosophía became filosofía.)

Nevertheless, there was ambivalence in the application of this rule in Mexican toponyms: México was used alongside Méjico, Texas and Tejas, Oaxaca and Oajaca, Xalixco and Jalisco, etc., as well as in proper and last names: Xavier and Javier, Ximénez and Jiménez, Roxas and Rojas are spelling variants still used today. In any case, the spelling Méjico for the name of the country is little used in Mexico or the rest of the Spanish-speaking world today. The Real Academia Española itself recommends the spelling "México".

In present-day Spanish, México is pronounced [ˈmexiko] or [ˈmehiko], the latter pronunciation used mostly in dialects of southern Mexico, the Caribbean, much of Central America, some places in South America, and the Canary Islands and western Andalusia in Spain where [x] has become a voiceless glottal fricative ([h]),[22][23] while [ˈmeçiko] in Chile and Peruvian coast where voiceless palatal fricative [ç] is an allophone of [x] before palatal vowels [i], [e].

Normative spelling in Spanish

[edit]México is the predominant Spanish spelling variant used throughout Latin America, and universally used in Mexican Spanish, whereas Méjico is used infrequently in Spain and Argentina. During the 1990s, the Spanish Royal Academy recommended that México be the normative spelling of the word and all its derivatives, even though this spelling does not match the pronunciation of the word, but that both forms with “x” or “j” are still orthographically correct.[24] Since then, the majority of publications adhere to the new norm in all Spanish-speaking countries even though the disused variant can still be found.[25] The same rule applies to all Spanish toponyms in the United States, and on some occasions in the Iberian Peninsula, even though in most official or regional languages of Spain (Asturian, Leonese and Catalan) and Portuguese, the x is still pronounced [ʃ].

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tibón, Gutierre (1980 2a edición), Historia del nombre y de la fundación de México, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, págs. 97-141. ISBN 9681602951 9789681602956

- ^ Rafael Romo (26 November 2012). "After nearly 200 years, Mexico may make the name official". CNN. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Historia de la Ciudad de México Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine Gobierno del Distrito Federal

- ^ Decreto Constitucional para la Libertad de la América Mexicana Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ¿Puede ser libre la Nueva España?

- ^ "Universidad Anáhuac". Archived from the original on 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ A Nahuatl Interpretation of the Conquest Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Constitución federal de los Estados Unidos mexicanos (1824)

- ^ Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States (1824) Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine (original scans with Spanish and English text): Texas Constitutions, University of Texas at Austin; also see Printing History Archived 2013-08-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1857)

- ^ Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1917)

- ^ 1917 Constitution of Mexico, Official Site of the Mexican Government (English)

- ^ Mexico's President Calderon seeks to change country's name

- ^ Aguilar-Moreno, M. Handbook to Life in the Aztec World, p. 19. Facts of Life, Inc. (New York), 2006.

- ^ a b Gobierno del Estado de México. Nombre del Estado de México Archived 2007-04-27 at the Wayback Machine. (in Spanish)

- ^ Karttunen, Frances. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl, p. 145. University of Oklahoma Press (Norman), 1992.

- ^ An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl - Frances Karttunen p145

- ^ Tibón, Gutierre (1980 2a edición), Historia del nombre y de la fundación de México, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, págs. 97-141. ISBN 9681602951 9789681602956

- ^ "Mexica - Gran Diccionario Náhuatl".

- ^ "Mexicatl - Gran Diccionario Náhuatl".

- ^ Evolution of the pronunciation of x Real Academia Española

- ^ PronounceNames.com· (23 September 2012). "How to Pronounce Mexico - PronounceNames.com" (Video upload). YouTube. Google Inc. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Canfield, D[elos] Lincoln (1981), Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas

- ^ Real Academia Española Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas

- ^ "Mexico" Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary