Quadrophenia (film)

| Quadrophenia | |

|---|---|

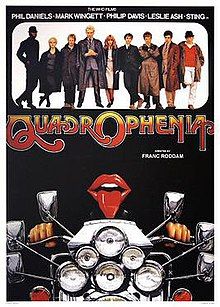

UK theatrical release poster by Renato Casaro | |

| Directed by | Franc Roddam |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Quadrophenia by the Who |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Brian Tufano |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production companies | The Who Films Ltd Polytel Films Curbishley-Baird Enterprises |

| Distributed by | Brent Walker Film Distributors |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 120 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £2 million[2] |

| Box office | $1,050,000[3] is |

Quadrophenia is a 1979 British drama film, based on the Who's 1973 rock opera of the same name. It was directed by Franc Roddam in his feature directing debut. Unlike the adaptation of Tommy, Quadrophenia is not a musical film, and the band does not appear live in the film.

The film, set in London in 1964, depicts a period of emotional turmoil in the life of Jimmy Cooper (Phil Daniels), a young Mod who escapes from his dead-end job as a postroom boy by dancing, partying, taking amphetamines, riding his scooter and brawling with Rockers.

Plot

[edit]In 1964, young London Mod Jimmy Cooper, disillusioned with his parents and a dull job as a post-room boy at an advertising firm, vents his teenage angst by taking amphetamines, partying, riding scooters and brawling with Rockers, accompanied by his Mod friends Dave, Chalky and Spider.

An attack by hostile Rockers on Spider leads to a retaliatory attack on Jimmy's childhood friend Kevin, one of the rival Rockers. Jimmy initially participates, but on realising the victim is Kevin, he berates the other attackers but does not stop them, instead riding away on his scooter, revving his engine loudly in frustration.

A planned bank holiday weekend away provides the excuse for the rivalry between Mods and Rockers to escalate, as both groups descend on the seaside town of Brighton. Jimmy plans to be noticed as a 'face' and hints to Steph – a girl on whom he has a crush – that he would like her to ride with him, but she confirms plans to ride instead with Pete, an older, well-heeled Mod.

To prepare for the weekend, the friends attempt to buy some recreational drugs from London gangster Harry North but are cheated with fake pills. After vandalising the drug-seller's car in retaliation, they desperately rob a pharmacy, finding a large quantity of their favourite "blues".

After an early morning group ride from London to the south coast, the friends gather on the seafront, where Jimmy first sees a flamboyant scooter-riding Mod he describes as Ace Face. Later, in a dance hall, Jimmy suggests that he will help Steph, whose escort is now chatting to an attractive American girl, to dance with Ace Face but on the dance floor ushers her away to dance by himself. Steph leaves Jimmy to dance with Ace Face, whereupon Jimmy plots to gain attention by climbing up onto the balcony-edge and dancing with much applause, annoying Ace Face. After diving into the audience, Jimmy is ejected by bouncers. Steph's escort leaves with the American girl.

The lads spend the night sleeping rough, meet up at a cafe the following morning, then proceed along the promenade, where a series of running battles ensues. As the police corner the rioters, Jimmy escapes down an alleyway with Steph and they have sex. When the pair emerge, they find themselves amidst the melee just as police are detaining rioters. Jimmy is arrested and detained with the volatile Ace Face. When fined a hefty £75—equivalent to £1,900 in 2023—Ace Face mocks the magistrate by offering to pay on the spot with a cheque, impressing the fellow Mods with his presumed wealth.

Back in London, Jimmy becomes severely depressed. His mother throws him out after finding his stash of amphetamine pills. He then leaves his job, spends his severance package on more pills and learns that Steph is now his friend Dave's girlfriend. After briefly fighting with Dave, the following morning his rejection is confirmed by Steph, and his beloved Lambretta scooter is damaged in a crash involving a Royal Mail parcel van. Jimmy takes a train back to Brighton, taking increasing levels of pills and becoming more emotionally unstable.

Lonely and unsure what to do with himself, he revisits the scenes of the riots and his encounter with Steph. Then Jimmy is shocked to discover that his idol, Ace Face, has a menial job as a bellboy at the Grand Brighton Hotel. Jimmy steals Ace's Vespa scooter and heads to Beachy Head, riding close to the cliff-edge. For a time, he appears to be having an enjoyable ride in the sunshine, but then he stops and glares miserably at the sea. Finally, the scooter is seen crashing over the cliff-top, which is where the film began (with Jimmy walking back against a sunset backdrop).

Cast

[edit]- Phil Daniels as Jimmy Cooper

- Leslie Ash as Steph

- Philip Davis as Chalky

- Mark Wingett as Dave

- Sting as Ace Face

- Ray Winstone as Kevin Herriot, Jimmy's childhood friend

- Gary Shail as Spider

- Garry Cooper as Peter Fenton, Steph's boyfriend

- Toyah Willcox as Monkey

- Trevor Laird as Ferdy

- Andy Sayce as Kenny

- Kate Williams as Mrs Cooper, Jimmy's mother

- Michael Elphick as Mr George Cooper, Jimmy's father

- Kim Neve as Yvonne Cooper, Jimmy's sister

- Benjamin Whitrow as Mr Fulford, Jimmy's employer

- Daniel Peacock as Danny

- Jeremy Child as Agency Man

- John Phillips as Magistrate

- Timothy Spall as Harry the Projectionist

- Patrick Murray as Des the projectionist assistant

- George Innes as Cafe Owner

- John Bindon as Harry North, gangster

- P. H. Moriarty as Barman at Villain Club

- Hugh Lloyd as Mr Cale

- Gary Holton as aggressive Rocker 1

- John Altman as Johnny 'John the Mod' Fagin

- Jesse Birdsall as aggressive Rocker 2

- Olivier Pierre as Jimmy and Danny's tailor

- Julian Firth as drugged up Mod

- Simon Gipps-Kent as party host (uncredited)

- Mickey Royce as Ken 'Jonesy' Jones

- Dave Cash as newsreader (uncredited)

- John Blundell as the Rockers leader (uncredited)

John Lydon (Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols) screen-tested for the role of Jimmy Cooper. The distributors of the film refused to insure him for the role and he was replaced by Phil Daniels.[4]

Most of the cast were reunited after 28 years at Earls Court on 1 and 2 September 2007 as part of The Quadrophenia Reunion at the London Film & Comic Con run by Quadcon.co.uk.[5] Subsequently, the cast agreed to be part of a Quadrophenia Convention at Brighton in 2009.[5]

Production

[edit]

Several references to the Who appear throughout the film as "Easter eggs", including an anachronistic inclusion of a repackaged Who album that was not available at the time, a clip of the band performing "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere" on the television series Ready Steady Go!, pictures of the band and a "Maximum R&B" poster in Jimmy's bedroom, and the inclusion of "My Generation" during a party gatecrashing scene. The film was almost cancelled when Keith Moon, the drummer for the Who, died, but in the words of Roddam, the producers, Roy Baird and Bill Curbishley, "held it together" and the film was made.[citation needed]

Only one scene in the film was shot in the studio; all others were on location. Beachy Head, where Jimmy considers suicide at the film's ending, is 14 miles from Saltdean, the site of the real-life cliffside death of a young mod in 1964 that Roddam has said inspired Townshend's original concept, though Townshend has denied this.[6]

Jeff Dexter, a club dancer and disc jockey fixture in the Sixties London music scene was the DJ in the club scenes, and was the uncredited choreographer of 500 extras for the ballroom and club scenes. He also choreographed Sting's feet in his dance close-ups. Dexter managed America.

Trevor Laird (Ferdy) was scripted to appear in a party scene kissing and having sex with a white girl, but was excluded from the scene by associate producer John Peverall due to concerns that it could cause problems with distributors in South Africa and the southern United States. Toyah Willcox has said that cast members discussed going on strike over the incident.[7]

Soundtrack

[edit]Quadrophenia is the soundtrack album to the 1979 film of the same name, which refers to the 1973 rock opera Quadrophenia.[8] It was initially released on Polydor Records in 1979 as a cassette and LP and was re-released as a compact disc in 1993 and 2001. The album was dedicated to Peter Meaden, a prominent Mod and first manager of the Who, who had died a year before the album's release.[citation needed]

The album contains ten of the seventeen tracks from the original rock opera Quadrophenia (as not all of the tracks were used in the film). These are different mixes from those that appear on the 1973 album as they were remixed in 1979 by John Entwistle. The most notable difference is the track "The Real Me" (used for the title sequence of the film) which features a different bass track, more prominent vocals and a more definite ending.[9] Most of the tracks are also edited to be slightly shorter. The soundtrack also includes three tracks by the Who that did not appear on the 1973 album.[citation needed]

Release

[edit]The film was first shown during the Cannes Film Festival on May 14, 1979. The film had its premiere at the Plaza cinema in London on 16 August 1979.[10] It opened to the public the following day and grossed £36,472 in its opening week from four cinemas in London, placing second behind Moonraker at the London box office.[10][11]

Reception

[edit]Janet Maslin, reviewing the film for The New York Times in 1979, called it "...gritty and ragged and sometimes quite beautiful", creating a "...slice-of-life movie that feels tremendously authentic in its sentiments as well as its details."[12] Maslin states that the director's scenes of youth battles "...capture a fierce, dizzying excitement that epitomizes a kind of youthful extreme."[12] Reviewer Brian Gibson from Vue Weekly (Edmonton, Canada) stated that "Roddam's look back at an angsty young man in '65 is a throwback to the kitchen-sink dramas that began plumbing the depths of working class lives then. Reeking with a restless teen spirit, Quadrophenia leads us down adolescence's blind alleys of rebellion."[13][14] Critic Matt Brunson from Creative Loafing stated that the film "[m]anages to be both quintessentially British and irrefutably universal", giving it a 3.5/4 score.[15] Reviewer Eric Melin from Scene-Stealers.com states that the film has a "...gritty, realistic feel and the themes of youthful rebellion and confusion are absolutely timeless, magnified by the specificity of the setting rather than being limited by it"; he also gave the movie a 3.5/4 score.[16] Reviewer Christopher Long from Movie Metropolis commented that "[w]hen you're an angry young man [like the main character], there's no better way to prove you're an individual than to dress and act exactly like everybody else"; Long gave the film a 6/10 score.[17]

Dennis Schwartz from Ozus' World Movie Reviews stated that the "...film lives through the superb raw angst-ridden performance of [lead] Phil Daniels"; Schwartz gave the movie a B+.[14] Critic Cole Smithey from ColeSmithey.com called the film a "...glorious representational story of male teen angst that transcends its British locations and great music with a sense of the confused romantic notions that young men the world over carry with them"; Smithey gave the film an A+.[14] Reviewer Ken Hanke from the Mountain Xpress (Asheville, NC) called it a "[d]isappointing film version of a great concept album"; he gave the film a 3/5 score.[14] Film critic Jeffrey M. Anderson from Combustible Celluloid states that where the film "...succeeds[, it does so] through its devil-may-care attitude and energy"; on the other hand, Anderson states that the film "...feels like a low-budget homemade movie from the period."[14]

Rotten Tomatoes collected reviews from 14 critics and gave Quadrophenia a 100% rating.[14]

The New York Times placed the film on its Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[18]

Home media

[edit]Sirius Publishing, Inc. released the film on the now defunct MovieCD format in 1991. The package included 3 discs for the movie itself along with other promotional material for the format and other films offered by Sirius on MovieCD. The packaging also carries the logo for Rhino Home Video indicating some form of involvement in this release.[19]

Universal Pictures Home Entertainment first released the film on DVD in the United Kingdom in 1999 with an 8-minute montage featurette. It used the VHS print, resulting in a much lower-quality video than expected. Following this in the United States was a special edition by Rhino, which included a remastered letterboxed wide screen transfer, a commentary, several interviews, galleries, and a quiz. However, it was a shorter cut of the film, with several minutes of footage missing.[citation needed]

Rhino Home Video released the film on DVD on 25 September 2001.[20]

On 7 August 2006, Universal improved upon their original UK DVD with a Region 2 two-disc special edition. The film was digitally remastered and included a new commentary by Franc Roddam, Phil Daniels and Leslie Ash. Disc 2 features an hour-long documentary and a featurette with Roddam discussing the locations.[21] Unlike their previous DVD, it was the complete, longer version, and it was matted to the correct aspect ratio.[citation needed]

The Criterion Collection released a special edition version of this movie on 28 August 2012, on both DVD and Blu-ray formats.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Quadrophenia (X)". British Board of Film Classification. 19 March 1979. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex (18 August 2011). "Quadrophenia: back when Britain's youngsters ran riot". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 298. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ Catterall, Ali; Wells, Simon (2002). Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since the Sixties. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-714554-6.

- ^ a b "QUADCON The Quadrophenia Movie Convention". Archived from the original on 8 November 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Simon Wells,Quadrophenia's Lost Mod?, Blogspot, 27 June 2009

- ^ Abigail Gillibrand, Quadrophenia cast threatened strike as Trevor Laird 'couldn't be seen with white girl', Metro.co.uk, 15 September 2019

- ^ "The Who Official Band Website – Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon | | Quadrophenia – Original Soundtrack". Thewho.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "The Who – Quadrophenia (1979 Soundtrack)". Thewho.info. 4 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Four-way triumph". Screen International. 25 August 1979. p. 2.

- ^ "London's Top Ten". Screen International. 25 August 1979. p. 1.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (2 November 1979). "Movie Review – Quadrophenia – Screen: Rock Drama From a Who Album:Mods and Rockers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Quadrophenia – Vue Weekly". vueweekly.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Quadrophenia – Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Brunson, Matt. "Quadrophenia, Titanic among new home entertainment titles". Creative Loafing Charlotte. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "'Quadrophenia' Criterion Blu-ray Review". www.scene-stealers.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "QUADROPHENIA – Blu-ray review – Movie Metropolis". 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. The New York Times via Internet Archive. Published April 29, 2003. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Quadrophenia (First ed.). Scottsdale, AZ: Sirius Publishing, Inc. 1991.

- ^ Rivero, Enrique (21 September 2001). "Quadrophenia' Director Happy DVD Prompted Restoration". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2001. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Pete Townshend – Who I Am: the autobiography". Thewho.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ali Catterall and Simon Wells, Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since The Sixties (Fourth Estate, 2001), ISBN 0-00-714554-3

External links

[edit]- 1979 films

- 1979 drama films

- 1970s British films

- 1979 independent films

- British coming-of-age drama films

- British independent films

- British musical drama films

- British teen drama films

- 1970s coming-of-age drama films

- 1979 directorial debut films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s musical drama films

- 1970s teen drama films

- Films based on albums

- Films based on operas

- Films directed by Franc Roddam

- Films set in 1964

- Films set in Brighton

- Films set in London

- Films shot at EMI-Elstree Studios

- Films shot in East Sussex

- Films shot in London

- Mod revival

- Pete Townshend

- Quadrophenia

- Rock musicals

- Teen musical films

- The Who

- Universal Pictures films

- Mod (subculture)

- English-language independent films

- English-language musical drama films

- 1979 musical films