Titus (film)

| Titus | |

|---|---|

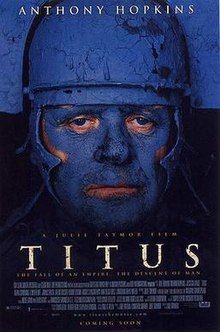

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Julie Taymor |

| Screenplay by | Julie Taymor |

| Based on | Titus Andronicus by William Shakespeare |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Luciano Tovoli |

| Edited by | Françoise Bonnot |

| Music by | Elliot Goldenthal |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Fox Searchlight Pictures (North America) Buena Vista International (United Kingdom and Ireland) Medusa Distribuzione (Italy) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 162 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million |

| Box office | $2.92 million[2] |

Titus is a 1999 epic surrealist historical drama film written, co-produced, and directed by Julie Taymor in her feature directorial debut, based on William Shakespeare's tragedy Titus Andronicus. A co-production between Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the film stars Anthony Hopkins in the title role of Titus Andronicus, the Roman army general, chronicling his downfall following a victorious return from war. It was produced by Overseas Filmgroup and Clear Blue Sky Productions and released by Fox Searchlight Pictures.

The film received mixed reviews from critics and grossed approximately $2.9 million worldwide against a budget of $18 million, becoming a box-office bomb, although it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Costume Design.

Plot

[edit]A boy eating lunch in a 1950s-style kitchen plays war with his surrounding toys. A bomb blast outside the window frightens him under the table from where he is rescued and taken to an Amphitheatre, where an invisible audience cheers. The boy finds himself in the role of Young Lucius and watches as an army resembling the Terracotta Army enters; Romans under the command of Titus Andronicus, the general at the center of the play, return victorious from war. They bring back as spoils Tamora, Queen of the Goths, her sons, and Aaron the Moor. Titus sacrifices Tamora's eldest son, Alarbus, so the spirits of his 21 dead sons might be appeased. Tamora eloquently begs for the life of Alarbus, but Titus refuses her plea.

Caesar, the Emperor of Rome, dies. His sons Saturninus and Bassianus squabble over who will succeed him. The Tribune of the People, Marcus Andronicus, announces the people's choice for new emperor is his brother, Titus. He refuses the throne and hands it to the late emperor's eldest son Saturninus, much to the latter's delight. The new emperor states he will take Lavinia, Titus' daughter, as his bride, to honor and elevate the family. She is already betrothed to Saturninus' brother, Bassianus, who steals her away. Titus' surviving sons aid in the couple's run for the Pantheon, where they are to marry. Titus, angry with his sons because in his eyes they're being disloyal to Rome, kills his son Mutius as he defends the escape. The new emperor, Saturninus, dishonors Titus and marries Tamora instead. Tamora persuades the Emperor to feign forgiveness to Bassianus, Titus and his family and postpone punishment to a later day, thereby revealing her intention to avenge herself on all the Andronici.

During a hunting party the next day, Tamora's lover, Aaron the Moor, meets Tamora's remaining sons, the sadistic Chiron and Demetrius. The two argue over which should take sexual advantage of the newly-wed Lavinia. Aaron easily persuades them to ambush Bassianus and kill him in the presence of Tamora and Lavinia, in order to have their way with her. Lavinia begs Tamora to stop her sons, but Tamora refuses. Chiron and Demetrius throw Bassianus' body in a pit, as Aaron directed them, then take Lavinia away and rape her. To keep her from revealing what she saw and endured, they cut out her tongue as well as her hands, replacing them with tree branches. When Marcus discovers her, he begs her to reveal the identity of her assailants; Lavinia leans towards the camera and opens her bloodied mouth in a silent scream.

Aaron frames Titus' sons Martius and Quintus for the murder of Bassianus with a forged letter outlining their plan to kill him. Angry, the Emperor arrests them. Later on, Marcus takes Lavinia to her father, who is overcome with grief. He and his remaining son Lucius beg for the lives of Martius and Quintus, but the two are found guilty and are marched off to execution. Aaron enters and tells Titus, Lucius and Marcus that the emperor will spare the prisoners if one of the three sacrifices a hand. Each demands the right to do so. Titus has Aaron cut off his (Titus's) left hand and take it to the emperor. Aaron's story is revealed to have been false, as a messenger brings Titus the heads of his sons and his own severed hand. In Renaissance semiotics, the hand is a representation of political and personal agency. With his hand chopped off, Titus has truly lost power.[3] Desperate for revenge, Titus orders Lucius to flee Rome and raise an army among their former enemy, the Goths.

Titus' grandson (Lucius' son and the boy from the opening), who helped Titus read to Lavinia, complains she will not leave his books alone. In the book, she indicates to Titus and Marcus the story of Philomela, in which a similarly mute victim "wrote" the name of her wrongdoer. Marcus gives her a stick to hold with her mouth and stumps. She writes the names of her attackers on the ground. Titus vows revenge. Feigning madness, he ties written prayers for justice to arrows and commands his kinsmen to aim them at the sky so they may reach the gods. Understanding the method in Titus' "madness", Marcus directs the arrows to land inside the palace of Saturninus, who is enraged by this added to the fact Lucius is at the gates of Rome with an army of Goths.

Tamora delivers a mixed-race child, fathered by Aaron. To hide his affair from the Emperor, Aaron kills the nurse and flees with the baby. Lucius, marching on Rome with an army of Goths, captures Aaron and threatens to hang the infant. To save the baby, Aaron reveals the entire plot to Lucius, relishing every murder, rape and dismemberment.

Tamora, convinced of Titus' madness, approaches him along with her two sons, dressed as the spirits of Revenge, Murder, and Rape. She tells Titus she (as a supernatural spirit) will grant him revenge if he will convince Lucius to stop attacking Rome. Titus agrees, sending Marcus to invite Lucius to a feast. "Revenge" offers to invite the Emperor and Tamora and is about to leave, but Titus insists "Rape" and "Murder" stay with him. She agrees. When she leaves, Titus' servants bind Chiron and Demetrius. Titus cuts their throats, while Lavinia holds a basin with her stumps to catch their blood. He plans to cook them into a pie for their mother.

The next day, during the feast at his house, Lavinia enters the dining room. Titus asks Saturninus whether a father should kill his daughter if she is raped. When the Emperor agrees, Titus snaps Lavinia's neck, to the horror of the dinner guests, and tells Saturninus what Tamora's sons did. When Saturninus demands Chiron and Demetrius be brought before him, Titus reveals they were in the pie Tamora enjoyed, and kills Tamora. Saturninus kills Titus after which Lucius kills Saturninus to avenge his father's death.

Back in the Roman Arena, Lucius tells his family's story to the people and is proclaimed Emperor. He orders his father Titus and sister Lavinia to be buried in the family monuments, Saturninus be given a proper burial, Tamora's body to be thrown to the wild beasts, and Aaron be buried chest-deep and left to die of thirst and starvation. Aaron is unrepentant to the end. Young Lucius, who appears to have lost his taste for violence after witnessing the bloody cycle of revenge, carefully picks up Aaron's child and reverts back to the boy from the beginning at the now silently empty Amphitheatre before carrying him away into the sunrise.

Cast

[edit]- Anthony Hopkins as Titus Andronicus, victorious Roman General who declines a nomination for Emperor upon his return to Rome. Following a post-war ritual of executing the proudest warrior of his enemy, the vanquished Goths, Titus draws the ire of Tamora, unaware of her inevitable appointment as the Queen of Rome.

- Jessica Lange as Tamora, defeated Queen of the Goths, who swears revenge against Titus and the Andronicus family for the atrocities visited upon her eldest son, an executed prisoner of war, using her newly claimed powers as Queen of Rome.

- Alan Cumming as Saturninus, older brother to Bassianus and newly crowned Emperor of Rome. Spurned by his attempts at claiming Lavinia as his new bride, he forsakes the Andronicus family and turns instead to Tamora as his new bride.

- Colm Feore as Marcus Andronicus, Roman Senator and staunch ally of his brother, the ailing Titus.

- James Frain as Bassianus, one of the deceased emperor's sons and younger brother to Saturninus.

- Laura Fraser as Lavinia, daughter of Titus and fiancée of Bassianus.

- Harry Lennix as Aaron, servant and illicit lover to Tamora, and the chief architect of her vengeful plans against the Andronicus family.

- Angus Macfadyen as Lucius, Titus' eldest son and loyal soldier. Following his failed attempts at freeing his condemned brothers, Lucius is banished from Rome and defects to the Goths, where he rallies a sizable army to challenge Saturninus.

- Osheen Jones as Young Lucius, Titus' grandson and a key character who observes most of the key events.

- Matthew Rhys as Demetrius, one of Tamora's sons.

- Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Chiron, one of Tamora's sons.

- Kenny Doughty as Quintus, one of Titus' sons.

- Colin Wells as Martius, one of Titus' sons.

- Blake Ritson as Mutius, one of Titus' sons.

- Raz Degan as Alarbus, Tamora's eldest son who is sacrificed, setting the events of the play into motion.

- Geraldine McEwan as the Nurse, who brings Aaron his son.

- Bah Souleymane as Aaron's infant child

- Mary Costa as Mourner[4]

Differences from the original text

[edit]Apart from the deliberate anachronisms, the film follows the play quite closely. One of the experimental concepts in the film was that the character of Young Lucius (Titus' grandson) is initially introduced as a boy from the present who finds himself transported to the fantastical reality of the film after being brought to an Amphitheatre. At the beginning of the film, his toy soldiers turn into Titus' Roman army. At the end, when Titus' son Lucius avenges his father by condemning the villainous Aaron to a painful death, the boy takes pity on Aaron's infant son; carrying him away from the violence of that world as he walks slowly into the sunrise, reverting to his original self as he leaves the empty Amphitheatre. This ending is perhaps more positive than the ending of other productions of the play, including Taymor's stage production, in which Young Lucius is fixated upon the "tiny black coffin" holding the dead infant.[5]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Julie Taymor took Shakespeare's script, added various linking scenes without dialogue (while cutting some of the text) and set the play in an anachronistic fantasy world that uses locations, costumes and imagery from many periods of history, including Ancient Rome and Mussolini's Italy, to give the impression of a Roman Empire that survived into the modern era. The opening scenes commence with a heavily choreographed triumphal march of the Roman troops, complete with motorcycle outriders. The selection of music is similarly diverse.[6]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography took place at the Cinecittà studios in Rome and on location at various historic monuments. The arena that appears at the beginning and ending of the film is the Arena in Pula, Croatia. The Emperor's palace is represented by the Fascist Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana in Rome. Some shots of tunnels and ruins were filmed at Hadrian's Villa in Rome. The forest scenes were shot at Manziana, near Rome. Titus' house is represented by an old house near an aqueduct in Rome, and the streets where he rounds up his conspirators are the Roman Ghetto.[7]

Soundtrack

[edit]The score for Titus was composed by Elliot Goldenthal, Taymor's longtime friend and partner, and is a typical Goldenthal soundtrack with an epic, inventive, and dissonant feel.

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Titus was a box office bomb, earning only $22,313 on its opening weekend due to its limited release in only two theaters, ranking number 57 in the box office.[8] Its widest release in the US was only in 35 theaters, causing the film to earn only $2,007,290 in North America. Overseas, it grossed $252,390 in Chile, Mexico, and Spain,[9] culminating in a worldwide total of $2,920,616.[2]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 69% of 77 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6.6/10. The website's consensus reads: "The movie stretches too long to be entertaining despite a strong cast."[10] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 57 out of 100, based on 29 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[11]

Stephen Holden of The New York Times gave the film a positive review, making it a "Critic's Pick".[12] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times also praised Titus and gave it three and a half out of four stars, referring to the source material as "the least of Shakespeare's tragedies" and concluding, "Anyone who doesn't enjoy this film for what it is must explain: How could it be more? This is the film Shakespeare's play deserves, and perhaps even a little more."[13]

Scott Tobias of The A.V. Club wrote that "Titus strikes a near-impossible balance between magnificently cracked high camp and a more serious statement about corruption and the cycle of violence" and that "[Taymor's] forceful adaptation builds to a glorious payoff and Cumming's flamboyant performance alone—he's a sort of fascist Pee-wee Herman—seems enough to ensure Titus lasting cult status."[14]

Robin Askew wrote in a 2016 article for Bristol24-7 that the film is "brilliant and daring if under-appreciated."[citation needed]

Accolades

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "TITUS (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 19 April 2000. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Titus (1999) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Rowe, Katherine A. (1994). "Dismembering and Forgetting in Titus Andronicus". Shakespeare Quarterly. 45 (3): 279–303. doi:10.2307/2871232. JSTOR 2871232.

- ^ Puchko, Kristy (17 January 2012). "Mary Costa, Aurora – Disney Princesses Then and Now". TheFW. Screencrush Network. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ McCandless, David (2002). "A Tale of Two Tituses: Julie Taymor's Vision on Stage and Screen". Shakespeare Quarterly. 53 (4): 487–511. doi:10.1353/shq.2003.0025. JSTOR 3844238. S2CID 194032305.

- ^ BFI | Sight & Sound | Titus (1999) Archived 24 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Julie Taymor, DVD commentary.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 24-26, 1999". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. 27 December 1999. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Titus (1999) - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. 18 December 2002. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Titus". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Titus". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Stephen Holden (24 December 1999). "Titus (1999) Film Review; It's a Sort of Family Dinner, Your Majesty". The New York Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (21 January 2000). "Titus". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (26 December 1999). "Titus". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 72nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Retrieved 6 January 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alan A. Stone (April–May 2000). "Shakespeare's Tarantino Play". Boston Review.

- Anwar Brett (8 September 2000). "Titus (2000)". BBC Films.

External links

[edit]- Titus at IMDb

- Titus at Box Office Mojo

- Titus at Rotten Tomatoes

- Titus at Metacritic

- 1999 films

- 1999 directorial debut films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s Italian films

- American films based on plays

- American historical drama films

- British films based on plays

- British historical drama films

- English-language historical drama films

- Films about adultery

- Films about cannibalism

- Films about filicide

- Films based on Titus Andronicus

- Films directed by Julie Taymor

- Films scored by Elliot Goldenthal

- Films set in ancient Rome

- Films set in the Roman Empire

- Films shot at Cinecittà Studios

- Films shot in Croatia

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in Rome

- Fox Searchlight Pictures films

- Italian films based on plays

- Italian historical drama films

- Latin-language films

- Modern adaptations of works by William Shakespeare

- Rape and revenge films

- Satellite Award–winning films