Timeline of major famines in India during British rule

| Timeline of major famines in India during British rule | |

|---|---|

Map of famines in India between 1800 and 1878 | |

| Country | Company rule in India, British Raj |

| Period | 1765–1947 |

The timeline of major famines in India during British rule covers major famines on the Indian subcontinent from 1765 to 1947. The famines included here occurred both in the princely states (regions administered by Indian rulers), British India (regions administered either by the British East India Company from 1765 to 1857; or by the British Crown, in the British Raj, from 1858 to 1947) and Indian territories independent of British rule such as the Maratha Empire.

The year 1765 is chosen as the start year because that year the British East India Company, after its victory in the Battle of Buxar, was granted the Diwani (rights to land revenue) in the region of Bengal (although it would not directly administer Bengal until 1784 when it was granted the Nizamat, or control of law and order.) The year 1947 is the year in which the British Raj was dissolved and the new successor states of Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan were established. The eastern half of the Dominion of Pakistan would become the People's Republic of Bangladesh in 1971.

A "major famine" is defined according to a magnitude scale, which is an end-to-end assessment based on total excess death. According to it: (a) a minor famine is accompanied by less than 999 excess deaths); (b) a moderate famine by between 1,000 and 9,999 excess deaths; (c) a major famine by between 10,000 and 99,999 excess deaths; (d) a great famine by between 100,000 and 999,999 excess deaths; and (e) a catastrophic famine by more than 1 million excess deaths.[1]

The British era is significant because during this period a very large number of famines struck India.[2][3] There is a vast literature on the famines in colonial British India.[4] The mortality in these famines was excessively high and in some may have been increased by British policies.[5] The mortality in the Great Bengal famine of 1770 was between one and 10 million;[6] the Chalisa famine of 1783–1784, 11 million; Doji bara famine of 1791–1792, 11 million; and Agra famine of 1837–1838, 800,000.[7] In the second half of the 19th-century large-scale excess mortality was caused by: Upper Doab famine of 1860–1861, 2 million; Great Famine of 1876–1878, 5.5 million; Indian famine of 1896–1897, 5 million; and Indian famine of 1899–1900, 1 million.[8] The first major famine of the 20th century was the Bengal famine of 1943, which affected the Bengal region during wartime; it was one of the major South Asian famines in which anywhere between 1.5 million and 3 million people died.[9]

The era is significant also because it is the first period for which there is systematic documentation.[10] Major reports, such as the Report on the Upper Doab famine of 1860–1861 by Richard Baird Smith, those of the Indian Famine Commissions of 1880, 1897, and 1901 and the Famine Inquiry Commission of 1944, appeared during this period, as did the Indian Famine Codes.[11] These last, consolidating in the 1880s, were the first carefully considered system for the prediction of famine and the pre-emptive mitigation of its impact; the codes were to affect famine relief well into the 1970s.[12] The Bengal famine of 1943, the last major famine of British India occurred in part because the authorities failed to take notice of the famine codes in wartime conditions.[13] The indignation caused by this famine accelerated the decolonization of British India.[14] It also impelled Indian nationalists to make food security an important post-independence goal.[15][16] After independence, the Dominion of India and thereafter the Republic of India inherited these codes, which were modernized and improved, and although there were severe food shortages in India after independence, and malnutrition continues to the present day, there were neither serious famines, nor clear and undisputed or large-scale ones.[17][18][19][20][21] The economist Amartya Sen who won the 1998 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in part for his work on the economic mechanisms underlying famines, has stated in his 2009 book, The Idea of Justice:

Though Indian democracy has many imperfections, nevertheless the political incentives generated by it have been adequate to eliminate major famines right from the time of independence. The last substantial famine in India — the Bengal famine — occurred only four years before the Empire ended. The prevalence of famines, which had been a persistent feature of the long history of the British Indian Empire, ended abruptly with the establishment of a democracy after independence.[22]

Migration of indentured labourers from India to the British tropical colonies of Mauritius, Fiji, Trinidad and Tobago, Surinam, Natal and British Guyana has been correlated to a large number of these famines.[23][24] The first famine of the British period, the Great Bengal famine of 1770, appears in work of the Bengali language novelist Bankim Chandra Chatterjee;[25][26] the last famine of the British period, Bengal famine of 1943 appears in the work of the Indian film director, Satyajit Ray. The inadequate official response to the Great Famine of 1876–1878, led Allan Octavian Hume and William Wedderburn in 1883 to found the Indian National Congress,[27] the first nationalist movement in the British Empire in Asia and Africa.[28] Upon assumption of its leadership by Mahatma Gandhi in 1920, Congress was to secure India both independence and reconciliation.[29][30]

Timeline

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Map of famines in India between 1800 and 1878.

-

Engraving from The Graphic, October 1877, showing the plight of animals as well as humans in Bellary district, Madras Presidency, British India during the Great Famine of 1876–1878.

-

A photograph of a famine-stricken mother with a baby who at 3 months weighs 3 pounds. Photographer: W. W. Hooper. Great Famine of 1876–1878.

-

A poster envisioning the future of Bengal after the Bengal famine of 1943.

-

Government famine relief Ahmedabad, c. 1901.

-

"Famine in India" front cover of Illustrated London News, February 21, 1874.

-

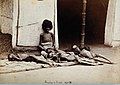

Five emaciated children during the famine of 1876–1878, India. Photographer: W. W. Hooper.

-

An illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing homeless people eating on the sidewalk during the Bengal famine of 1943.

-

Illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing a starvation fatality in the Bengal famine of 1943.

-

Famine in Bengal: Grain-boats on the Ganges. Illustrated London News, March 21, 1874.

-

Drawing, titled "Famine in India," from The Graphic, February 27, 1897, showing a bazaar scene in India with shoppers, many of whom are emaciated, buying grain from a merchant's shop.

-

A group of emaciated women and children in Bangalore, India, famine of 1876–1878. Photographer: WW Hooper.

-

Famine relief at Bellary, Madras Presidency, The Graphic, October 1877.

-

Engraving from The Graphic, October 1877, showing two forsaken children in the Bellary district of the Madras Presidency during the famine.

-

Famine tokens of 1874 Bihar famine, and the 1876 Great famine.

-

The "Cooks' Room" at a famine relief camp, Madras Presidency, 1876–1878. Photographer: W. W. Hooper.

-

Cartoon from Punch, "Mending the Lesson" showing Miss Prudence warning John Bull about handing out too much charity to the needy during the Bihar famine of 1873–1874, and the latter's own interpretation of the Law of Supply and Demand.

-

Victims of the Great Famine of 1876–1878 in British India, pictured in 1877. The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The death toll from this famine is estimated to be in the range of 5.5 million people.[38]

See also

[edit]- Famine in India (British rule)

- Company rule in India

- Drought in India

- Famine in India

- List of famines

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to the writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn, The Lancet's estimates were an overestimate based on a mistake in the population changes in India from 1891-1901. The Lancet, states McMinn, declared that the population increased only by 2.8 million for the whole of India, while the actual increase was 7.5 million according to him. The Lancet source, contrary to McMinn claims, states that the population increased from 287,317,048 to 294,266,702 (2.42%). Adjusting for changes in census tracts, the total population increase in India was only 1.49% between 1891 and 1901, a major decline from the decadal change of 11.2% observed between 1881 and 1891, according to The Lancet article on April 13, 1901. It attributes the decrease in population change rate to excess mortality from successive famines and the plague.[44]

- ^ a b According to a 1901 estimate published in The Lancet, this and other famines in India between 1891 and 1901 caused 19,000,000 deaths from "starvation or to the diseases arising therefrom",[40][43] an estimate criticised by the writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn.[45]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Rubin, Olivier (2016), Contemporary Famine Analysis, Springer Briefs in Political Science, SpringerNature, p. 14, ISBN 978-3-319-27304-4

- ^ Siegel, Benjamin Robert (2018), Hungary Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India, Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-108-42596-4,

For nearly two centuries, India's British administrators had presided over innumerous famines, each dismissed in turn as a Malthusian inevitability.

- ^ Simonow, Joanna (2022), "Famine relief in colonial South Asia, 1858–1947: Regional and global perspectives.", in Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria (eds.), Routledge Handbook of the History of Colonialism in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 497–509, ISBN 978-1-138-36484-4,

(p. 497–498) Famines and food scarcities of various degrees accompanied colonial rule in India. Only about a dozen of them have received scholarly attention. For long, this attention has been distributed rather unevenly, with literature on famines in the second half of the nineteenth century being more extensive than research dealing with famines in the early colonial period. But, with the growth of scholarly work on the latter, the balance is shifting.

- ^ Simonow, Joanna (2022), "Famine relief in colonial South Asia, 1858–1947: Regional and global perspectives.", in Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria (eds.), Routledge Handbook of the History of Colonialism in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 497–509, ISBN 978-1-138-36484-4,

(p. 510) Despite the copious literature on famines in colonial India, the history of famines still provides scholars of South Asia with new points of departure to deviate from common scales of analysis and to explore largely untouched primary sources

- ^ Earle, Rebecca (2020), Feeding the People: The Politics of the Potato, Cambridge University Press, p. 114, ISBN 978-1-108-48406-0,

Horrendous famines causing millions of deaths continued to scourge India's inhabitants throughout the period of colonial rule. British policies proved utterly inadequate to the task of alleviating starvation and were in many cases directly responsible for it.

- ^ Datta, Rajat (2000). Society, economy, and the market: commercialization in rural Bengal, c. 1760-1800. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 262, 266. ISBN 81-7304-341-8. OCLC 44927255.

- ^ Simonow, Joanna (2022), "Famine relief in colonial South Asia, 1858–1947: Regional and global perspectives.", in Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria (eds.), Routledge Handbook of the History of Colonialism in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 497–509, ISBN 978-1-138-36484-4,

(p. 497–498) In 1769/70 famine conditions surfaced in Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar, resulting in the estimated death of 10 million Indians in Bengal alone – a third of the province's population. Millions of Indians died of starvation in the south of India from 1781 to 1783, and a year later in north India as well because of the rapid succession of another major famine crisis. Droughts were frequent in the North-Western Provinces, in 1803/4, 1812/13, 1817–19, 1824–26, and 1833, often spilling over into severe subsistence crises. This spate of food crises anticipated the onset of yet another major famine in 1836/7, which threw the Doab region into havoc and caused the death of an estimated 15 to 20 per cent of the population.

- ^ Simonow, Joanna (2022), "Famine relief in colonial South Asia, 1858–1947: Regional and global perspectives.", in Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria (eds.), Routledge Handbook of the History of Colonialism in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 497–509, ISBN 978-1-138-36484-4,

(p. 497–498) In the second half of the nineteenth-century famine conditions devastated Orissa in 1866/7 and ravaged the Madras Presidency, the Deccan region, and the North-Western Provinces from 1876 to 1878. Even greater in scope were the famines of 1896/7 and 1899/1900, which held almost the entire subcontinent in their grip. ... Mortality was excessive during these latter famine crises. Historians have estimated that between 12 and 29 million died between 1876 and 1902.

- ^ Simonow, Joanna (2022), "Famine relief in colonial South Asia, 1858–1947: Regional and global perspectives.", in Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria (eds.), Routledge Handbook of the History of Colonialism in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 497–509, ISBN 978-1-138-36484-4,

(p. 497–498) Following the improvement of colonial mechanisms to identify and contain famine conditions, their scale decreased in the early twentieth century. Yet scarcities as well as outright famines continued to haunt India's agriculturalists. They were particular frequent during and in the aftermath of both world wars, when the wars' economic, social, and political repercussions increased the vulnerability of India's agricultural labourers to subsistence crises.11 It was not until the great Bengal Famine of 1943/4, however, which resulted in the death of an estimated 3 million Bengalis and displaced even more, that mass starvation again resulted in horrific sights of emaciated bodies and corpses filling the streets of urban centres of British India.12 Following the worst South Asian famine of the twentieth century, the nation's political elite prepared for independence even while the country remained on the brink of famine.

- ^ Roy, Tirthankar (June 2016), "Were Indian Famines 'Natural' Or 'Manmade?'" (PDF), London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History, Working Papers (243): 3,

All of the three interpretations - geography, manmade-as-political, and manmade-as-cultural - have been prominent in the scholarship and popular history of past Indian famines, especially for the time when detailed records of famines were kept. This starts as recently as the mid-nineteenth century, though the occurrence of famines in India has a much longer history. The years for which some systematic documentation exist were also the years when more than half of India was ruled first by the British East India Company (until 1858), and then the British Crown (1858-1947).

- ^ Dreze, Jean, "Famine Prevention in India", in Dreze, Jean; Sen, Amartya (eds.), The Political Economy of Hunger, Volume 2: Famine Prevention, Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, pp. 13–122, 33, ISBN 978-0-19-828636-3,

... an examination of the incidence of famines in India before and after the Famine Codes strongly suggests a contrast between the earlier period of famines and famine relief in India during the period on which this section will focus.

1770 Formidable famine in Bengal

1770-1858 Frequent and severe famines

1858 End of East India Company

1861 Report of Baird Smith on the 1860-1 famine

1861-80 Frequent and severe famines

1880 Famine Commission Report, followed by the introduction ofFamine Codes

1880-96 Very few famines

1896-7 Large-scale famine affecting large parts of India

1898 Famine Commission Report on the 1896—7 famine

1899-1900 Large-scale famine

1901 Famine Commission Report on the 1899-1900 famine

1901-43 Very few famines

1943 Bengal Famine

1945 Famine Commission Report on the Bengal Famine

1947 Independence - ^ Brennan, Lance (1984), "The Development of the Indian Famine Code", in Currey, Bruce; Hugo, Graeme (eds.), Famine as a Geographical Phenomenon, Dordrecht, Boston, Lancaster: D. Reidel Publishing Company; Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 91–112, 92, ISBN 978-94-009-6397-9,

These codes were not, of course, the first sets of administrative instructions for famine relief. Outhwaite discusses the Book of Orders issued during sixteenth century famines in England (Outhwaite 1978), and there were codes issued during the 1876-79 period in some provinces as their governments grappled with widespread and prolonged food crises. But the codes produced in the 1880s do seem to have been the first serious attempts to systematize the prediction of famine, and to set down steps to ameliorate its impact before its onset. ... The codes which eventually emerged were the product of a complex process beginning with the experience of the famines of 1876-9, continuing through the investigations of the Famine Commission, and ending with the discussions of the 'draft', 'provisional', and final provincial codes. This exercise produced answers to the major questions of famine relief which, though not immutable, were to influence famine policy for the following ninety years.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (1992), Individual Human Rights: The Relationship of Political and Civil Rights to Survival, Subsistence and Poverty, Washington DC, London, and Brussels: Human Rights Watch, p. 3, ISBN 1-56432-084-7, LCCN 92-74298,

Independence also came on the heels of a disastrous famine, that killed over one million people in Bengal in 1943. This famine occurred in part because the British authorities failed to implement the provisions of the famine code -- illustrating that the most sophisticated technical system is valueless unless it is used.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (1992), Individual Human Rights: The Relationship of Political and Civil Rights to Survival, Subsistence and Poverty, Washington DC, London, and Brussels: Human Rights Watch, p. 3, ISBN 1-56432-084-7, LCCN 92-74298,

The outrage caused by this famine intensified demands for immediate independence after the Second World War, and also ensured that a commitment to famine prevention would be at the top of the new government's political priorities.

- ^ Siegel, Benjamin Robert (2018), Hungary Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India, Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-108-42596-4,

Hunger had begun to emerge as a site of political contestation in the decades before independence, but it was in the wake of the Bengal famine of 1943 that Indian nationalists tied the promise of independence to the guarantee of food for all, drawing upon novel critiques of India's political economy.

- ^ Spielman, Katherine A.; Aggarwal, Rimjhim M (2017), "Household- vs. National-Scale Food Storage: Perspectives on Food Security from Archaeology and Contemporary India", Sustainability: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-1-107-07833-8,

The memory of famines during the British colonial period has strongly shaped the narrative, and consequently the mental model, that underlies the framing of food policy in India.

- ^ Szirmai, Adam (2015) [2005], Socio-Economic Development, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, p. 418, ISBN 978-1-107-04595-8,

If governments had imported limited amounts of food and taken responsibility for its distribution, prices could have been brought under control and famines could have been averted. Since independence in 1947, India has pursued such policies. Unlike what happened in China between 1958 and 1960, there have been no large-scale famines in India in the post-war period. A relatively open society and timely identification of food shortages are the prerequisites for success of a policy aimed at preventing famines.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (1992), Individual Human Rights: The Relationship of Political and Civil Rights to Survival, Subsistence and Poverty, Washington DC, London, and Brussels: Human Rights Watch, p. 3, ISBN 1-56432-084-7, LCCN 92-74298,

India provides the best example of a country that has successfully averted famine since Independence in 1947, despite repeated droughts and enduring chronic poverty. ... Since 1947, the Famine Codes — now renamed Scarcity Manuals — have been continually updated and improved. Their provisions have frequently been implemented -- most notably in 1966, 1973 and 1987. In all cases, they have prevented severe food shortages from degenerating into famine.

- ^ Siegel, Benjamin Robert (2018), Hungary Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India, Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-108-42596-4,

The independent nation has repeatedly defied gloomy predictions of outright famine. Yet India has remained in the thrall of pervasive malnutrition since independence, its citizens less food secure than those of any sub- Saharan African state.

- ^ Spielman, Katherine A.; Aggarwal, Rimjhim M (2017), "Household- vs. National-Scale Food Storage: Perspectives on Food Security from Archaeology and Contemporary India", Sustainability: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-1-107-07833-8,

Shortly after independence, the import of food (PL-480 packages from the United States) following the severe drought in the mid-1960s was seen as a tremendous embarrassment to the pride of a young nation. Consequently, emphasis was placed on maximizing national production of food by focusing on the most fertile regions of the country, and then distributing surplus food from these regions to those with food deficits through a centralized public distribution system. The green revolution in the late 196os/early 1970s accelerated agricultural growth at the national level and as Sen (1999) argues, 'Famines are easy to prevent if there is a serious effort to do so, and a democratic government, facing elections and criticisms from opposition partics and independent newspapers, cannot help but make such an effort.' In his opinion the establishment of a multi-party political system and a free press after independence were instrumental in preventing further famines in India.

- ^ Wood, Alan T. (2016) [2004], Asian Democracy in World History, Themes in World History, London and New York: Routledge, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-415-22942-5,

Famine in India was endemic during the years of British rule, and given the tripling of the Indian population since independence one might have expected famines to increase. Yet there has never been a serious famine in independent India. The presence of opposition parties and a free press has made the government far more responsive to local needs than it ever was under colonial or autocratic rule. One has only to contemplate the experience of China to appreciate the magnitude of this difference. There 30 million peasants died of starvation in the late 1950s and early 1960s — by far the greatest famine anywhere in the world at any time in history — as a direct resule of Mao Zedong's failed Great Leap Forward. Indeed, this ability to prevent famine may be one of democracy's greatest contributions. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has written that 'no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy — be it economically rich (as in contemporary Western Europe or North America) or relatively poor (as in postindependence India, or Botswana, or Zimbabwe).'

- ^ Sen, Amartya (2009), The Idea of Justice, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03613-0

- ^ Brennan, Lance; McDonald, John; Schlomowitz, Ralph; Aker, Eva (2013), "Towards and anthropometric theory of Indians under British rule", Well-being in India: Studies in anthropometric history, New Delhi: Readworthy, pp. 71–72,

The crucial methodological questions addressed in the regression analysis of cohorts of indentured workers in this paper is the effect of recruitment year on the pattern of change in height by birth cohort. In comparing recruits for Mauritius, Natal and Fiji, we have emphasized that varying recruitment conditions, besides long-term changes in disease and nutrition, influenced average height. ... The second and more general influence on recruiting patterns was the influence of famine. There were a number of substantial famines in India during the 19th century. Those which most affected the north Indian recruiting areas occurred in 1836–1836, 1866–1867, 1873–1874, 1878–1879, 1892, 1896–1897, 1899–1900.

- ^ Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India, 1857–1947, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, p. 362, ISBN 0-19-568430-3

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Marshall 2001, p. 179.

- ^ Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, p. 297, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1,

Despite any whimsy in implementation, the clarity of Gandhi's political vision and the skill with which he carried the reforms in 1920 provided the foundation for what was to follow: twenty-five years of stewardship over the freedom movement. He knew the hazards to be negotiated. The British must be brought to a point where they would abdicate their rule without terrible destruction, thus assuring that freedom was not an empty achievement. To accomplish this he had to devise means of a moral sort, able to inspire the disciplined participation of millions of Indians, and equal to compelling the British to grant freedom, if not willingly, at least with resignation. Gandhi found his means in non-violent satyagraha. He insisted that it was not a cowardly form of resistance; rather, it required the most determined kind of courage.

- ^ Corbett, Jim; Elwin, Verrier; Ali, Salim (2004), Lives in the Wilderness: Three Classic Indian Autobiographies, Oxford University Press,

The transfer of power in India, Dr Radhakrishnan has said, 'was one of the greatest acts of reconciliation in human history.'

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, pp. 501–502

- ^ Kumar 1983, p. 528.

- ^ Kumar 1983, p. 299.

- ^ Grove 2007, p. 80

- ^ Grove 2007, p. 83

- ^ a b c d e Fieldhouse 1996, p. 132

- ^ Kumar 1983, p. 529.

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 488

- ^ Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 4

- ^ a b Davis 2001, p. 7

- ^ a b C.A.H. Townsend, Final report of thirds revised revenue settlement of Hisar district from 1905-1910, Gazetteer of Department of Revenue and Disaster Management, Haryana, point 22, p. 11.

- ^ Safi, Michael (29 March 2019). "Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal famine – study". The Guardian.

- ^ The effect of famines on the population of India, The Lancet, Vol. 157, No. 4059, June 15, 1901, pp. 1713-1714;

Sven Beckert (2015). Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Random House. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-375-71396-5. - ^ The Census in India, The Lancet, Vol. 157, No. 4050, pp. 1107–1108

- ^ C.W. McMinn, Famine Truths, Half Truths, Untruths (Calcutta: 1902), p.87.[a]

- ^ Davis, Mike (2002-06-17). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (p. 151-158). Verso Books. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Davis, Mike (2002-06-17). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (p. 171-173). Verso Books. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Kumar 1983, p. 531.

References

[edit]History

[edit]- Marshall, P. J. (2001), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A concise history of modern India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006), India under colonial rule: 1700–1885, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3

Famines

[edit]- Arun Agrawal (2013), "Food Security and Sociopolitical Stability in South Asia", in Christopher B. Barret (ed.), Food Security and Sociopolitical Stability, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 406–427, ISBN 978-0-19-166870-8

- Appadurai, Arjun (1984), "How Moral Is South Asia's Economy?—A Review of Rural Society in Southeast India. by Kathleen Gough; Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The Famine of 1943-1944. by Paul R. Greenough; Subject to Famine: Food Crises and Economic Change in Western India, 1860- 1920. by Michelle B. McAlpin; Why They Did Not Starve: Biocultural Adaptation in a South Indian Village. by Morgan D. Maclachlan; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. by Amartya Sen" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 43 (3): 481–497, doi:10.2307/2055760, JSTOR 2055760, S2CID 56376629

- Ambirajan, S. (1976), "Malthusian Population Theory and Indian Famine Policy in the Nineteenth Century", Population Studies, 30 (1): 5–14, doi:10.2307/2173660, JSTOR 2173660, PMID 11630514

- Arnold, David (2013), "Hunger in the Garden of Plenty: The Bengal Famine of 1770", in Alessa Johns (ed.), Dreadful Visitations: Confronting Natural Catastrophe in the Age of Enlightenment, Taylor & Francis, pp. 81–112, ISBN 978-1-136-68396-1

- Arnold, David (1994), "The 'discovery' of malnutrition and diet in colonial India", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 31 (1): 1–26, doi:10.1177/001946469403100101, S2CID 145445984

- Arnold, David; Moore, R. I. (1991), Famine: Social Crisis and Historical Change (New Perspectives on the Past), Wiley-Blackwell. Pp. 164, ISBN 978-0-631-15119-7

- Attwood, Donald W. (2005), "Big Is Ugly? How Large-scale Institutions Prevent Famines in Western India", World Development, 33 (12): 2067–2083, doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.009

- Banik, Dan (2007), Starvation and India's Democracy, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-13416-8

- Bayly, C. A. (2002), Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1770–1870, Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. 530, ISBN 978-0-19-566345-7

- Bhatia, B. M. (1991), Famines in India: A Study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India With Special Reference to Food Problem, 1860–1990, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division. Pp. 383, ISBN 978-81-220-0211-9

- Bouma, Menno J.; van der Kay, Hugo J. (1996), "The El Niño Southern Oscillation and the historic malaria epidemics on the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka: an early warning system for future epidemics", Tropical Medicine and International Health, 1 (1): 86–96, doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-7.x, PMID 8673827

- Kumar, Dharma, ed. (1983), The Cambridge economic history of India, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2

- Chamberlain, Andrew T. (2006), Demography in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-45534-3

- Charlesworth, Neil (2002), Peasants and Imperial Rule: Agriculture and Agrarian Society in the Bombay Presidency 1850-1935, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52640-1

- Damodaran, Vinita (2007), "Famine in Bengal: A Comparison of the 1770 Famine in Bengal and the 1897 Famine in Chotanagpur", The Medieval History Journal, 10 (1&2): 143–181, doi:10.1177/097194580701000206, S2CID 162735048

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso Books, p. 7, ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- Drèze, Jean (1995), "Famine prevention in India", in Drèze, Jean; Sen, Amartya; Hussain, Althar (eds.), The political economy of hunger: Selected essays, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. 644, ISBN 978-0-19-828883-1

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2005) [1900], Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd (reprinted by Adamant Media Corporation), ISBN 978-1-4021-5115-6

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part I", Population Studies, 45 (1): 5–25, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145056, JSTOR 2174991, PMID 11622922

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part II", Population Studies, 45 (2): 279–297, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145446, JSTOR 2174784, PMID 11622922

- Dyson, Tim, ed. (1989), India's Historical Demography: Studies in Famine, Disease and Society, Riverdale MD: The Riverdale Company. Pp. ix, 296

- Fagan, Brian (2009), Floods, Famines, and Emperors: El Nino and the Fate of Civilizations, Basic Books. Pp. 368, ISBN 978-0-465-00530-7

- Famine Commission (1880), Report of the Indian Famine Commission, Part I, Calcutta

- Fieldhouse, David (1996), "For Richer, for Poorer?", in Marshall, P. J. (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 400, pp. 108–146, ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041557, PMID 11620403

- Gilbert, Martin (2003), The Routledge Atlas of British History, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-28147-8

- Government of India (1867), Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Enquire into the Famine in Bengal and Orissa in 1866, Volumes I, II, Calcutta

- O Grada, Cormac (1997), "Markets and famines: A simple test with Indian data", Economics Letters, 57 (2): 241–244, doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00228-0

- Greenough, Paul Robert (1982), Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The Famine of 1943-1944, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-503082-2

- Grove, Richard H. (2007), "The Great El Nino of 1789–93 and its Global Consequences: Reconstructing an Extreme Climate Even in World Environmental History", The Medieval History Journal, 10 (1&2): 75–98, doi:10.1177/097194580701000203, hdl:1885/51009, S2CID 162783898

- Hall-Matthews, David (2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 42 (1): 1–24, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07002892, S2CID 146232991

- Hall-Matthews, David (1996), "Historical Roots of Famine Relief Paradigms: Ideas on Dependency and Free Trade in India in the 1870s", Disasters, 20 (3): 216–230, Bibcode:1996Disas..20..216H, doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1996.tb01035.x, PMID 8854458

- Hardiman, David (1996), "Usuary, Dearth and Famine in Western India", Past and Present (152): 113–156, doi:10.1093/past/152.1.113

- Hill, Christopher V. (1991), "Philosophy and Reality in Riparian South Asia: British Famine Policy and Migration in Colonial North India", Modern Asian Studies, 25 (2): 263–279, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00010672, S2CID 144560088

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502), Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Kaiwar, Vasant (2016), "Famines of structural adjustment in colonial India", in Kaminsky, Arnold P; Long, Roger D (eds.), Nationalism and Imperialism in South and Southeast Asia: Essays Presented to Damodar R.SarDesai, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-351-99742-3

- Keim, Mark E. (2015), "Extreme Weather Events: The Role of Public Health in Disaster Risk Reduction as a Means for Climate Change Adaptation", in George Luber; Jay Lemery (eds.), Global Climate Change and Human Health: From Science to Practice, Wiley, p. 42, ISBN 978-1-118-60358-1

- Klein, Ira (August 1973), "Death in India, 1871-1921", The Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (4): 639–659, doi:10.2307/2052814, JSTOR 2052814, PMID 11614702, S2CID 41985737

- Maclachlan, Morgan D. (1983), Why They Did Not Starve: Biocultural Adaptation in a South Indian Village, Institute for the Study of Human Issues, ISBN 978-0-89727-001-4

- Maharatna, Arup (1996), The demography of famines: an Indian historical perspective, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563711-3

- McAlpin, Michelle Burge (2014), Subject to Famine: Food Crisis and Economic Change in Western India, 1860-1920, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-5592-6

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (Autumn 1983), "Famines, Epidemics, and Population Growth: The Case of India", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 14 (2): 351–366, doi:10.2307/203709, JSTOR 203709

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1979), "Dearth, Famine, and Risk: The Changing Impact of Crop Failures in Western India, 1870–1920", The Journal of Economic History, 39 (1): 143–157, doi:10.1017/S0022050700096352, S2CID 130101022

- McGregor, Pat; Cantley, Ian (1992), "A Test of Sen's Entitlement Hypothesis", The Statistician, 41 (3 Special Issue: Conference on Applied Statistics in Ireland, 1991): 335–341, doi:10.2307/2348558, JSTOR 2348558

- Mellor, John W.; Gavian, Sarah (1987), "Famine: Causes, Prevention, and Relief", Science, New Series, 235 (4788): 539–545, Bibcode:1987Sci...235..539M, doi:10.1126/science.235.4788.539, JSTOR 1698676, PMID 17758244, S2CID 3995896

- Muller, W. (1897), "Notes on the Distress Amongst the Hand-Weavers in the Bombay Presidency During the Famine of 1896–97", The Economic Journal, 7 (26): 285–288, doi:10.2307/2957261, JSTOR 2957261

- Nisbet, John (1901), Burma Under British Rule - and Before, vol. II, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd

- Owen, Nicholas (2008), The British Left and India: Metropolitan Anti-Imperialism, 1885–1947 (Oxford Historical Monographs), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. 300, ISBN 978-0-19-923301-4

- Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India, 1857–1947, 2nd edition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. xvi, 385, ISBN 978-0-19-568430-8

- Roy, Tirthankar (June 2016), Were Indian famines 'natural' or 'man-made'?, London School of Economics, Economic History, Working Papers No: 243/2016

- Seavoy, Ronald E. (1986), Famine in Peasant Societies, London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-25130-6

- Sen, A. K. (1977), "Starvation and Exchange Entitlements: A General Approach and its Application to the Great Bengal Famine", Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1: 33–59, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035349

- Sen, A. K. (1982), Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. ix, 257, ISBN 978-0-19-828463-5

- Sharma, Sanjay (1993), "The 1837–38 famine in U.P.: Some dimensions of popular action", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 30 (3): 337–372, doi:10.1177/001946469303000304, S2CID 143202123

- Siddiqi, Asiya (1973), Agrarian Change in a Northern Indian State: Uttar Pradesh, 1819–1833, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 222, ISBN 978-0-19-821553-0

- Stokes, Eric (1975), "Agrarian Society and the Pax Britannica in Northern India in the Early Nineteenth Century", Modern Asian Studies, 9 (4): 505–528, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012877, JSTOR 312079, S2CID 145085255

- Stone, Ian (25 July 2002), Canal Irrigation in British India: Perspectives on Technological Change in a Peasant Economy (Cambridge South Asian Studies), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 389, ISBN 978-0-521-52663-0

- Tomlinson, B. R. (1993), The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., ISBN 978-0-521-58939-0

- Washbrook, David (1994), "The Commercialization of Agriculture in Colonial India: Production, Subsistence and Reproduction in the 'Dry South', c. 1870–1930", Modern Asian Studies, 28 (1): 129–164, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011720, JSTOR 312924, S2CID 145422009

- Yang, Anand A. (1998), Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, Berkeley: University of California Press

Epidemics and Public Health

[edit]- Banthia, Jayant; Dyson, Tim (December 1999), "Smallpox in Nineteenth-Century India", Population and Development Review, 25 (4): 649–689, doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00649.x, JSTOR 172481, PMID 22053410

- Caldwell, John C. (December 1998), "Malthus and the Less Developed World: The Pivotal Role of India", Population and Development Review, 24 (4): 675–696, doi:10.2307/2808021, JSTOR 2808021

- Drayton, Richard (2001), "Science, Medicine, and the British Empire", in Winks, Robin (ed.), Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 264–276, ISBN 978-0-19-924680-9

- Derbyshire, I. D. (1987), "Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860-1914", Population Studies, 21 (3): 521–545, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00009197, S2CID 146480332

- Klein, Ira (1988), "Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India", Modern Asian Studies, 22 (4): 723–755, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00015729, JSTOR 312523, PMID 11617732, S2CID 42173746

- Watts, Sheldon (1999), "British Development Policies and Malaria in India 1897-c. 1929", Past and Present (165): 141–181, doi:10.1093/past/165.1.141, JSTOR 651287, PMID 22043526

- Wylie, Diana (2001), "Disease, Diet, and Gender: Late Twentieth Century Perspectives on Empire", in Winks, Robin (ed.), Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 277–289, ISBN 978-0-19-924680-9

![Victims of the Great Famine of 1876–1878 in British India, pictured in 1877. The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The death toll from this famine is estimated to be in the range of 5.5 million people.[38]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/India-famine-family-crop-420.jpg/120px-India-famine-family-crop-420.jpg?auto=webp)