Cultural depictions of tigers

Tigers have had symbolic significance in many different cultures. They are considered one of the charismatic megafauna, and are used as the face of conservation campaigns worldwide. In a 2004 online poll conducted by cable television channel Animal Planet, involving more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries, the tiger was voted the world's favourite animal with 21% of the vote, narrowly beating the dog.[1]

Mythology, religion and folklore

[edit]In Chinese mythology and culture, the tiger is one of the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. In Chinese art, the tiger is depicted as an earth symbol and equal rival of the Chinese dragon – the two representing matter and spirit respectively. The Southern Chinese martial art Hung Ga is based on the movements of the tiger and the crane. In Imperial China, a tiger was the personification of war and often represented the highest army General Officer,[2] while the emperor and empress were represented by a dragon and phoenix, respectively. The White Tiger (Chinese: 白虎; pinyin: Bái Hǔ) is one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellations. It is sometimes called the White Tiger of the West (Chinese: 西方白虎), and it represents the west and the autumn season.[2]

The tiger's tail appears in stories from countries including China and Korea, it being generally inadvisable to grasp a tiger by the tail.[3][4] In Korean mythology and culture, the tiger is regarded as a guardian that drives away evil spirits and a sacred creature that brings good luck – the symbol of courage and absolute power. For the people who live in and around the forests of Korea, the tiger considered the symbol of the Mountain Spirit or King of mountain animals.[citation needed] A man killed by a tiger would turn into a spiteful ghost, called "Changgwi" (Korean: 창귀), and must seek out the next victim to exchange fates in order to die in peace.[5]

In Buddhism, the tiger is one of the Three Senseless Creatures, symbolising anger, with the monkey representing greed and the deer lovesickness.[2] The Tungusic peoples considered the Siberian tiger a near-deity and often referred to it as "Grandfather" or "Old man". The Udege and Nanai called it "Amba". The Manchu people considered the Siberian tiger as "Hu Lin", the king.[6] In Hinduism, the god Shiva wears and sits on tiger skin.[7] The ten-armed warrior goddess Durga rides the tigress (or lioness) Damon into battle. In southern India the god Ayyappan was associated with a tiger.[8] Dingu-Aneni is the god in North-East India is also associated with tiger.[9]

In Bhutan, the tiger is venerated as one of the four powerful animals called the "four dignities", and a tigress is believed to have carried Padmasambhava from Singye Dzong to the Paro Taktsang monastery in the late 8th century.[10] In the Greco-Roman world, the tiger was depicted being ridden by the god Dionysus.[11] The Warli of western India worship the tiger-like god Waghoba. The Warli believe that shrines and sacrifices to the deity will lead to better coexistence with the local big cats, both tigers and leopards, and that Waghoba will protect them when they enter the forests.[12]

The weretiger replaces the werewolf in shapeshifting folklore in Asia;[13] in India they were evil sorcerers, while in Indonesia and Malaysia they were somewhat more benign.[14] In Taiwanese folk beliefs, Aunt Tiger portrays the story of a tiger, which turns into an old woman, abducts children at night and devours them to satisfy her appetite.[15]

Art

[edit]

Representations of tigers have been discovered dating at least as far back as 5000 BC, during the neolithic cultures that preceded China proper. The Four Symbols—the tiger, dragon, phoenix, and turtle—are extremely commonly depicted in Chinese art, even outside mythic and astrological contexts. For their supposed ability to scare off evil (cf. the legend of the nian), tiger images were also once popular Chinese New Year decorations, although they are now more commonly restricted to use during the Years of the Tiger. Similarly, tigers were long carved onto Chinese tombs and monuments as guardians against thieves.

The bi'an was considered a tigerlike dragon, one of the Dragon King's nine sons. Effigies of its tiger head were placed prominently above the entrances of Chinese prisons as warnings and guardians. Traditional Chinese chamber pot urinals were traditionally shaped and decorated to resemble crouching tigers, causing them to become known as huzis.

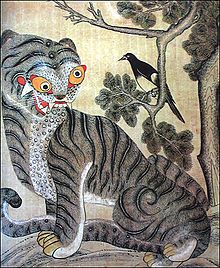

In Korea, the painting "Jakhodo" (in leopard paintings, "Jakpyodo"; "pyo" means leopard) is about a magpie and a tiger. The letter "jak" means magpie; "ho" means tiger; and "do" means painting. Since the work is known to keep away evil influence, there is a tradition to hang the art piece in the house in the first month of the lunar calendar. On a branch of a green pine tree sits a magpie and the tiger (or leopard), with a humorous expression, looks up at the bird. The tiger in "Jakhodo" does not look anything like a strong creature with power and authority.

Kkachi horangi, paintings depicting magpies and tigers, was a prominent motif in the minhwa folk art of the Joseon period. Kkachi pyobeom paintings depict magpies and leopards. In kkachi horangi paintings, the tiger, which is intentionally given a ridiculous and stupid appearance (hence its nickname "idiot tiger" 바보호랑이), represents authority and the aristocratic yangban, while the dignified magpie represents the common people. Hence, kkachi horangi paintings of magpies and tigers were a satire of the hierarchical structure of Joseon's feudal society.[16][17]

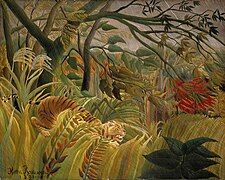

Tigers have also been featured in Western paintings. George Stubbs draw realistic portraits of the cats, including one that was partially dissected. Eugène Delacroix depicted tigers in several of this paintings and drawings including A Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother (1830–1831) which shows the gentler side of the animal. In the oil painting Tiger in a Tropical Storm (1891), Henri Rousseau compares the tiger's ferocity with the storm around it. Tigers are also featured in Salvador Dali's Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944), were they are emerging from a fish, which is emerging from a pomegranate.[18]

-

Tiger, 1912 by Franz Marc

Literature and media

[edit]

In the Hindu epic Mahabharata, the tiger is fiercer and more ruthless than the lion.[19] William Blake's poem "The Tyger" portrays the tiger as a menacing and fearful animal, and the tiger Shere Khan in Rudyard Kipling's 1894 The Jungle Book is the mortal enemy of the human protagonist. The tiger is featured in the mediaeval Chinese novel Water Margin, where the cat battles and is slain by the bandit Wu Song,[20] Yann Martel's novel Life of Pi features the title character surviving shipwreck for months on a small boat with a large Bengal tiger while avoiding being eaten. The story was adapted in Ang Lee's film Life of Pi in 2012.[21]

Friendly tiger characters include Tigger in A. A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh and Hobbes of the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, both represented as stuffed animals coming to life.[22] The Tiger Who Came to Tea by Judith Kerr is one of the best selling children's books of all time.[23] Tony the Tiger is a famous mascot for the breakfast cereal Frosted Flakes.[24]

Music

[edit]

The wooden yu used to mark the end of pieces of music in yayue, the ritual music of ancient China's Zhou dynasty, was shaped like a tiger. It was played by using a bamboo whisk to strike the tiger's head and to run across the serrated back's 27 teeth, which sometimes aligned with the stripes of the instrument's tiger decoration. Although the Classic of Music that instructed creation and use of the yayue instruments is almost entirely lost and aspects of modern construction and performance are guesswork or replacement, a few temples—including the main Taiwan Confucian Temple—still use reconstructed yu for Confucian ceremonies. It is also used in Korean court ritual in the form of the eo.

Heraldry and emblems

[edit]

The tiger is one of the animals displayed on the Pashupati seal of the Indus Valley civilisation. The tiger was the emblem of the Chola Dynasty and was depicted on coins, seals and banners.[25] The seals of several Chola copper coins show the tiger, the Pandyan emblem fish and the Chera emblem bow, indicating that the Cholas had achieved political supremacy over the latter two dynasties. Gold coins found in Kavilayadavalli in the Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh have motifs of the tiger, bow and some indistinct marks.[26] The tiger symbol of Chola Empire was later adopted by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and the tiger became a symbol of the unrecognised state of Tamil Eelam and Tamil independence movement.[27] The Bengal tiger is the national animal of India and Bangladesh.[28] The Malaysian tiger is the national animal of Malaysia.[29] The Siberian tiger is the national animal of South Korea.[citation needed] The Tiger is featured on the logo of the Delhi Capitals Indian Premier League team.[citation needed]

A yellow tiger was used as the primary emblem of the flag of the short-lived Republic of Formosa declared by the Chinese residents on Taiwan in 1895 after the treaty ending the First Sino-Japanese War yielded control of the island from the Qing Empire to the Empire of Japan. The Japanese army overcame formal resistance within the year.

In European heraldry, the tyger, a depiction of a tiger as imagined by European artists, is among the creatures used in charges and supporters. This creature has several notable differences from real tigers, lacking stripes and having a leonine tufted tail and a head terminating in large, pointed jaws. A more realistic tiger entered the heraldic armory through the British Empire's expansion into Asia, and is referred to as the Bengal tiger to distinguish it from its older counterpart. The Bengal tiger is not a common creature in heraldry, but is used as a supporter in the arms of Bombay and emblazoned on the shield of the University of Madras.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ "Endangered tiger earns its stripes as the world's most popular beast". The Independent. December 6, 2004. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c Cooper, J. C. (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- ^ "Tiger's Tail". Cultural China. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Curry, L. S. & Chan-Eun, P. (1999). A Tiger by the tail and other Stories from the heart of Korea. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 9780313069345.

- ^ Bella Kim (2021-09-28). "'CHANGGWI' Review: What Ghosts Think of Us". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Matthiessen, P.; Hornocker, M. (2008). Tigers in the Snow (reprint ed.). Paw Prints. ISBN 9781435296152.

- ^ Sivkishen (2014). Kingdom of Shiva. New Delhi: Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Balambal, V. (1997). 19. Religion – Identity – Human Values – Indian Context. Bioethics in India: Proceedings of the International Bioethics Workshop in Madras: Biomanagement of Biogeoresources, 16–19 January 1997. Eubios Ethics Institute. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ^ Nanditha, K. (2010). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-8184751826. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Tandin, T.; Penjor, U.; Tempa, T.; Dhendup, P.; Dorji, S.; Wangdi, S. & Moktan, V. (2018). Tiger Action Plan for Bhutan (2018-2023): A landscape approach to tiger conservation (Report). Thimphu, Bhutan: Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.14890.70089.

- ^ Dunbabin, K. M. D. (1999). Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32, 44. ISBN 978-0-521-00230-1.

- ^ Nair, R.; Dhee; Patli, O.; Surve, N.; Andheria, A.; Linnell, J. D. C. & Athreya, V. (2021). "Sharing spaces and entanglements with big cats: the Warli and their Waghoba in Maharashtra, India". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 2. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2021.683356. hdl:11250/2990288.

- ^ Summers, M. (1933). The Werewolf in Lore and Legend (2012 ed.). Mineola: Dover Publications. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-517-18093-8.

- ^ Newman, P. (2012). Tracking the Weretiger: Supernatural Man-Eaters of India, China and Southeast Asia. McFarland. pp. 96–102. ISBN 978-0-7864-7218-5.

- ^ Hulick, J. (2009). "Review of Auntie Tiger". Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. 62 (6): 267. doi:10.1353/bcc.0.0662. S2CID 144937417.

- ^ "까치호랑이". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ KOREA Magazine March 2017. Korean Culture and Information Service. 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Thapar, V. (2004). Tiger: The Ultimate Guide. New Delhi: CDS Books. pp. 248–259. ISBN 1-59315-024-5.

- ^ Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa. "SECTION LXVIII". The Mahabharata. Translated by Ganguli, K. M. Retrieved 15 June 2016 – via Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ Green, S. (2006). Tiger. Reaktion Books. pp. 72–73, 78, 125–27. ISBN 978-1861892768.

- ^ Castelli, J.-C. (2012). The Making of Life of Pi: A Film, a Journey. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0062114136.

- ^ Kuznets, L. R. (1994). When Toys Come Alive: Narratives of Animation, Metamorphosis, and Development. Yale University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0300056457.

- ^ "The Tiger Who Came to Tea". BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ Gifford, C. (2005). Advertising & Marketing: Developing the Marketplace. Heinemann-Raintree Library. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1403476517.

- ^ Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja (2009) Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 84.

- ^ Singh, U. (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi, Chennai: Pearson Education. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Somasundaram, D. (2013). Scarred Communities: Psychosocial Impact of Man-made and Natural Disasters on Sri Lankan Society. New Delhi: Sage Publications India. ISBN 9789353881054.

- ^ "National Animal". Government of India Official website. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012.

- ^ DiPiazza, F. (13 February 2024). Malaysia in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-2674-2.

- ^ Fox-Davies, A. (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T. C. and E. C. Jack. pp. 191–192.