Sultanate of Tidore

Sultanate of Tidore كسلطانن تدوري Kesultanan Tidore | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1081?/1450–1967 | |||||||

Seal used by Sultan Amiruddin Syah c. 1803 | |||||||

Sultanate of Tidore in 1800 | |||||||

| Capital | Tidore | ||||||

| Common languages | North Moluccan Malay[1] Tidore | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Sultan, Kië ma-kolano | |||||||

• 1081 | Kolano Syahjati (Muhammad Naqil) | ||||||

• 15th century–1500s | Jamaluddin | ||||||

• 1947–1967 | Zainal Abdin Shah | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 1081?/1450 | ||||||

• Disestablished | 1967 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||

The Sultanate of Tidore (Malay: كسلطانن تدوري, romanized: Kesultanan Tidore; sometimes Kerajaan Tidore) was a sultanate in Southeast Asia, centered on Tidore in the Maluku Islands (presently in North Maluku, Indonesia). It was also known as Duko, its ruler carrying the title Kië ma-kolano (Ruler of the Mountain). Tidore was a rival of the Sultanate of Ternate for control of the spice trade and had an important historical role as binding the archipelagic civilizations of Indonesia to the Papuan world.[2] According to extant historical records, in particular the genealogies of the kings of Ternate and Tidore, the inaugural Tidorese king was Sahjati or Muhammad Naqil whose enthronement is dated 1081 in local tradition. However, the accuracy of the tradition that Tidore emerged as a polity as early as the 11th century is considered debatable. Islam was only made the official state religion in the late 15th century through the ninth King of Tidore, Sultan Jamaluddin. He was influenced by the preachings of Syekh Mansur, originally from Arabia.[3] In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Sultans tended to ally with either Spain or Portugal to maintain their political role but were finally drawn into the Dutch sphere of power in 1663. Despite a period of anti-colonial rebellion in 1780–1810, the Dutch grip on the sultanate increased until decolonization in the 1940s. Meanwhile, Tidore's suzerainty over Raja Ampat and western Papua was acknowledged by the colonial state.[4] In modern times, the sultanate has been revived as a cultural institution.[5]

Origins

[edit]According to later historical traditions, the four kingdoms of North Maluku (Ternate, Tidore, Bacan, and Jailolo) had a common root. A story that arose after the introduction of Islam says that the common ancestor was an Arab, Jafar Sadik, who married a heavenly nymph (bidadari) and sired four sons, of whom Sahjati became the first kolano (ruler) of Tidore.[6] The term kolano might be a Javanese loanword borrowed from the name of the character in Panji tales, pointing at early cultural influences from Java.[7] The first eight kolanos are proto-historical as there are no contemporary sources on Tidore until the early 16th century.[8] The ninth, Ciri Leliatu, was reportedly converted to Islam by an Arab, Syekh Mansur, and named his oldest son after the preacher.[9] According to European sources, Islam was accepted by the North Malukan elite in about the 1460s–1470s. Ciri Leliatu's son Sultan al-Mansur ruled when the Portuguese first visited Maluku in 1512 and met the remnants of the Magellan expedition in 1521.[10] By that time the sultanate lived in an uneasy and ambiguous relationship with its close neighbour Ternate. Though frequently at war, the Tidore rulers held a ritual precedence position since their daughters regularly married Ternatan sultans and princes.[11]

Geographical extent

[edit]Together, the two sultanates Ternate and Tidore exercised suzerainty over a huge area from Sulawesi to West Papua. Supposedly, the ninth Tidore ruler Ciri Leliatu invaded the Papuan island Gebe, a local power center, in the late 15th century and thereby gained access to valuable forest products of the Raja Ampat Islands and New Guinea.[12] According to records in the Sonyine Malige Museum, the start of Tidore's influence in these quarters was due to his son, al-Mansur or Ibnu Mansur, who bonded a naval leader of Waigeo, Gurabesi from Biak (later known by the European title Kapitan), as well as with a Sangaji of Patani, Sahmardan. According to tradition they launched an expedition to Papua in 1453 and created bonds with Papuan villages with Gurabesi's assistance.[13] These regions were held separately by the Korano Ngaruha (lit. Four Kings) or Raja Ampat. The four sub-kings were Kolano Salawati, Kolano Waigeo, Kolano Waigama, and Kolano Umsowol or Lilinta. Furthermore, the Papoua Gam Sio (lit. The Papua Nine Negeri) included Sangaji Umka, Gimalaha Usba, Sangaji Barei, Sangaji Boser, Gimalaha Kafdarun, Sangaji Wakeri, Gimalaha Warijo, Sangaji Mar, and Gimalaha Warasay. Lastly, the Mafor Soa Raha (lit. The Mafor Four Soa) included Sangaji Rumberpon, Sangaji Rumansar, Sangaji Angaradifa, and Sangaji Waropen.[14] Historical tradition also relates that Tidore in 1498 attacked Sran centered on Adi island in West Papua and installed a vassal king (later known by the European title Mayor). The first vassal ruler, Wanggita, was followed by his descendants for three generations; their influence extended to Karufa and Arguni Bay.[15] However, the Papuan dependencies were only documented by Europeans in the 17th century.[16] Considering that New Guinea had little economic value for them, the Dutch promoted Tidore as suzerain of Papua. By 1849, Tidore's borders had been extended to the proximity of the current international border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.[17] Tidore furthermore ruled over parts of Halmahera and islands close by, especially the Gamrange area in the southeast (Maba, Weda, and Patani). At times, Tidore controlled East Seram and laid claims to outlying places such as Buru and Aru.[18]

Administration

[edit]The base of Tidorese society was the soa, socio-political units headed by bobato (headmen). A bobato was a state official but also a guardian of the interests of his community. On the basic level in the outlying areas (Halmahera, etc.) were various kimelaha or gimalaha (local leaders formally appointed by the sultan), who in turn stood under sangaji (honoured princes) who lorded as vassals over various territories belonging to the Sultanate. At the center was a state council consisting of 31 members including the 27 bobato, two hukum (magistrates), one kapiten laut (sea lord), and a jojau (chief minister). Moreover, the sultan employed utusan or envoys who visited the various outer areas under Tidore's sway and collected tributes.[19] If these levies (which could be in the form of slaves or their value equivalent in massoy, nutmeg, turtle shell, and other goods) were not met, a punitive Hongi expedition would be launched on behalf of the sultan of Tidore, usually by other rajas of different regions under him.[20]

Alliance with Spain

[edit]Tidore established a loose alliance with the Spanish in the sixteenth century, starting with the visit of the Magellan expedition in 1521. The aim was to counter the power of Ternate, which had allied with the Portuguese since 1512. At the start, this did not mean much due to the rare Spanish visits, and Tidore suffered a series of serious defeats at the hands of the Portuguese in 1524, 1526, 1529, 1536, and 1560. However, the Ternatan sultan Babullah broke with the Portuguese in 1570 and greatly expanded his territory in all directions. Feeling slighted, the Tidorese under Gapi Baguna allied with the Portuguese and allowed them to build a fort on their island in 1578.[21] After the merger of Portugal and Spain in 1581, Spain, already established in the Philippines, took over the Iberian initiative and carried out several more or less abortive interventions in Maluku to strengthen Iberian influence in the region. Since the Spanish and Portuguese realms were administered separately under the Habsburg kings, the Portuguese were however able to hang on for the next 24 years and kept several forts on the island. There was also a limited presence of Catholic missionaries in Tidore, who managed to convert a few members of the elite.[22] While there was much mutual distrust between the Tidorese and the Spaniards and Portuguese, for Tidore the Spanish presence helped resist incursions by their Ternatan enemy. Nevertheless, it lost vital territories in Halmahera by the end of the 16th century, which had supplied Tidore Island with sago, a vital stock of food.[23]

Arrival of the VOC

[edit]

In 1605, the Dutch of the United East India Company (VOC) took over Ambon as a part of their policy to control the lucrative trade in spices. The next step was to invade Tidore and defeat the Portuguese garrison in May in the same year. This was basically the end of the Portuguese presence in Maluku. However, the Spaniards soon retaliated; they launched a major attack on Ternate from their Philippines base in April 1606 and were assisted by the Tidorese. The enterprise was successful, the power of Ternate was curbed, and Tidore was allowed to take over certain Ternatan dependencies. This in turn alerted the VOC since Spain and the Dutch Republic were at war in Europe, and their rivalry had global implications. The VOC allied with the new Ternatan sultan and launched their own expedition in 1607 that recovered part of Ternate.[24] As a result, Ternate became heavily dependent on the Dutch, who also made incursions in Tidore over the next years and secured some coastal forts. Sultan Mole Majimu of Tidore held on to his allegiance to Spain, although some Tidorese princes leaned towards Ternate and the VOC. By this time the royal clan had split into two rivalling lineages which made for rapid throne shifts. The Spanish authorities found the sultans to be a nuisance rather than a help to the Spanish power.[25]

A relatively pro-VOC sultan, Saifuddin, came to the throne in 1657 by pushing the other royal lineage aside. He agreed with the Dutch to eradicate all clove trees in his realm, in line with the VOC monopoly policy on the spice trade. In return he received a yearly compensation.[26] The Spanish in the Philippines, who needed all available resources for their defense against the Sino-Japanese pirate lord Koxinga, decided to withdraw from Tidore in 1662. This was effectuated in 1663–1666.[27] With the Spaniards gone, a new contract in 1667 spelled out the relations between the VOC and Tidore. In the 17th century Tidore became one of the most independent kingdoms in the region, resisting direct control by Dutch East India Company (VOC). Particularly under Sultan Saifuddin's rule (1657–1687), the Tidore court was skilled at using Dutch payment for spices for gifts to strengthen traditional ties with Tidore's traditional periphery. As a result, he was widely respected by many local populations and had little need to call on the Dutch for military help in governing the kingdom, as Ternate frequently did.[28]

Rebellion and colonial penetration

[edit]

Tidore remained an independent kingdom, albeit with frequent Dutch interference, until the late eighteenth century. Like Ternate, Tidore allowed the Dutch spice eradication program (extirpatie) to proceed in its territories. This program, intended to strengthen the Dutch spice monopoly by limiting production to a few places, impoverished Tidore as well as its Ternate neighbour and weakened its control over its periphery. A treaty in 1768 forced Sultan Jamaluddin to cede his rights to East Seram which had been granted Tidore in 1700, which created great anger among the elite. The unrest caused the VOC authorities to depose Jamaluddin in 1779 and to force his successor Patra Alam to conclude a new contract that abrogated the old one from 1667. With this document (1780), Tidore was turned from an ally to a vassal and thus lost its independence.[29] One of the exiled Jamaluddin's sons, Nuku, reacted to this by starting a rebellion in 1780, seeking support in the marginal areas of the Tidore realm. The uprising took on violently anti-Dutch features where Islam was an important ideological glue. In this period, Gebe and Numfor were able to increase their influence, with Gebe serving as a base when Nuku assembled a fleet of 300 perahus for plundering raids.[30] Nuku in particular found allies in Halmahera, Seram, and the Raja Ampat Islands, but also in places that had not been subservient to Tidore, such as the Kei and Aru Islands. After several shifts, Nuku allied with the British, who were at war with the Dutch after 1795 and were in the process of conquering Dutch colonial possessions. In 1797 he captured Bacan and then Tidore itself, expelling the VOC-backed Sultan Kamaluddin. Nuku was enthroned as Sultan Muhammad al-Mabus Amiruddin. As such he took care to restore the defunct Jailolo sultanate to return to the traditional, pre-European quadripartition of Maluku.[31] In 1801 Ternate was captured by the British and Tidorese after a long siege. However, the Peace of Amiens in Europe changed the strategic positions in the next year already, since the Dutch were allowed to retake their positions in Maluku. After the death of Nuku in 1805, his brother, Sultan Zainal Abidin, proved unable to resist the Dutch-Ternatan attacks. Tidore was lost in 1806 and the sultan fled, finally dying in exile in 1810.[32]

Tidore was subjected to an increasing implementation of colonial rule in the 19th century. A treaty was signed in 1817 where the sultan and grandees received annual subsidies. Tidore was included in the Residency of Ternate together with Ternate, Bacan, Halmahera, and dependencies. The infamous hongi expeditions, which had eradicated unauthorized spice trees in Maluku and kept the Papuan lands in subordination, were finally abolished in 1859–1861.[33] The title of sultan lapsed in 1905 and was replaced by a regency. The rights of Tidore in West New Guinea were formally upheld, but the Dutch Residents of Ternate tried to diminish Tidorese's influence in those quarters since it was not considered in the interests of the Papuans.[34] It was only after the outbreak of the Indonesian revolution that the Dutch authorities allowed a new sultan to be enthroned, Zainal Abidin Alting (r. 1947–1967). After the gaining of Indonesian independence in 1949, old monarchical institutions were abolished. However, the historical status of the sultan played a certain role in bolstering Indonesian claims to Dutch New Guinea. Thus Zainal Abidin was appointed Governor of Irian Barat (Papua) during the years 1956–1961, at a time when the region was still under Dutch control. After his governorship, he settled in Ambon where he died in 1967.[35][full citation needed] No new sultan was appointed. However, with the increasing interest in Indonesia for local tradition after the end of the Suharto era, some aspects of the sultanate were taken up. Titular sultans have been chosen from among the different royal branches since 1999.

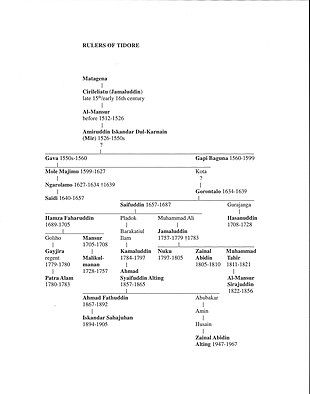

List of sultans

[edit]

| Kolanos and sultans of Tidore | Reign |

|---|---|

| Sahjati[a] | |

| Busamuangi | |

| Suhu | |

| Balibungah | |

| Duku Madoya | |

| Kie Matiti | |

| Sele | |

| Matagena | |

| Ciri Leliatu (Jamaluddin) | late 15th/early 16th century |

| Al-Mansur | before 1512–1526 |

| Mir (Amiruddin Iskandar Dulkarna'in) | 1526–1550s |

| Gava[b] | 1550s–1560 |

| Gapi Baguna | 1560–1599 |

| Mole Majimu | 1599–1627 |

| Ngarolamo | 1627–1634 |

| Gorontalo | 1634–1639 |

| Saidi | 1640–1657 |

| Saifuddin | 1657–1687 |

| Hamza Faharuddin | 1689–1705 |

| Abu Falalal Mansur | 1705–1708 |

| Hasanuddin | 1708–1728 |

| Malikulmanan | 1728–1757 |

| Jamaluddin | 1757–1779 |

| Gayjira (regent) | 1779–1780 |

| Patra Alam | 1780–1783 |

| Kamaluddin | 1783–1797 |

| Nuku, Muhammad al-Mabus Amiruddin | 1797–1805 |

| Zainal Abidin | 1805–1810 |

| Muhammad Tahir | 1811–1821 |

| Ahmad al-Mansur Sirajuddin | 1822–1856 |

| Ahmad Saifuddin Alting | 1856–1865 |

| Ahmad Fathuddin | 1867–1892 |

| Iskandar Sahajuhan | 1893–1905 |

| Zainal Abidin Alting | 1947–1967 |

| Haji Djafar Dano Junus | 1999–2012 |

| Husain Syah | 2014–present |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ François Valentijn (1724) mentions two early Tidorese Muslim kings, Nuruddin (c. 1343) and Hasan Syah (c. 1372), not known to the local king lists; see F. S. A. de Clercq (1890), Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate. Leiden: Brill, p. 148.

- ^ Tidore king list has Kië Mansur and Iskandar Sani as sultans between Mir and Gapi Baguna, though these names are not found in the contemporary sources; see F. S. A. de Clercq (1890), Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate. Leiden: Brill, p. 321.

References

[edit]- ^ Widjojo, Muridan Satrio (2009). The Revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-Cultural Alliance-making in Maluku, C.1780-1810. BRILL. p. 151. ISBN 978-90-04-17201-2.

- ^ Trajectories of the early-modern kingdoms in eastern Indonesia

- ^ Sejarah Kerajaan Tidore.

- ^ Heather Sutherland (2021) Seaways and Gatekeepers; Trade and State in the Eastern Archipelagos of Southeast Asia, c. 1600-c. 1906. Singapore: NUS Press, p. 190-2, 225-6, 266-8, 368-70.

- ^ Kirsten Jäger (2018) Das Sultanat Jailolo; Die Revitalisierung von "traditionellen" politischen Gemeinwesen in Indonesien. Berlin: Lit Verlag, p. 196.

- ^ C. F. van Fraassen (1987), Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, Vol. I, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Andaya, Leonard Y. (1993). The World of Maluku: eastern Indonesia in the early modern period. University of Hawaii Press. p. 59. hdl:10125/33430. ISBN 978-0-8248-1490-8.

- ^ F. S. A. de Clercq (1890). Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate. Leiden: Brill, p. 321.

- ^ P. J. B. C. Robidé van der Aa (1879). Reizen naar Nederlandsch Nieuw-Guinea. 's-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), Turbulent times past in Ternate and Tidore. Banda Naira: Rumah Budaya Banda Naira, p. 20–25.

- ^ Extensive genealogical explanation in C. F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, pp. 13–30.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 105; P. J. B. C. Robidé van der Aa (1879), p. 19.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 105.

- ^ Wanggai, Tony V. M. (2008). Rekonstruksi Sejarah Islam di Tanah Papua (PDF) (Thesis) (in Indonesian). UIN Syarif Hidayatullah. Retrieved 2022-01-30.

- ^ Usmany, Desy Polla (2017-06-03). "Sejarah Rat Sran Raja Komisi Kaimana" [éHistory of Rat Sran King of Kaimana]. Jurnal Penelitian Arkeologi Papua Dan Papua Barat (in Indonesian). 6 (1): 85–92. doi:10.24832/papua.v6i1.45. ISSN 2580-9237.

- ^ F. C. Kamma (1948). "De verhouding tussen Tidore en de Papoese eilanden in legende en historie", Indonesië 1947–49, I, p. 552; Tidore-Papuan relations in general discussed in Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 99–110.

- ^ Swadling, Pamela; Wagner, Roy; Laba, Billai (2019-12-01). Plumes from Paradise. Sydney University Press. p. 17. doi:10.30722/sup.9781743325445. ISBN 978-1-74332-544-5.

- ^ Muridan Widjojo (2009). The revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-cultural alliance-making in Maluku, c. 1780-1810. Leiden: Brill, p. 52–53; Hans Hägerdal & Emilie Wellfelt (2019), "Tamalola: Transregional connectivities, Islam, and anti-colonialism on an Indonesian island", Wacana, No. 20–23.

- ^ Muridan Widjojo (2009), p. 47–49.

- ^ Swadling, Pamela; Wagner, Roy; Laba, Billai (2019-12-01). Plumes from Paradise. Sydney University Press. p. 146. doi:10.30722/sup.9781743325445. ISBN 978-1-74332-544-5.

- ^ Hubert Jacobs (1980) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. II. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 9*; Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 133.

- ^ Hubert Jacobs (1980), Documenta Molucensia, Vol. II. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute.

- ^ Leonard Anadaya (1993), p. 169–70.

- ^ Margaret Makepeace, "Middleton, Sir Henry (d. 1613)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed., January 2008

- ^ Hubert Jacobs (1984), Documenta Molucensia, Vol. III. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 6.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 171.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 155–56.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 170–174.

- ^ Muridan Widjojo (2009), pp. 52–56.

- ^ Swadling, Pamela; Wagner, Roy; Laba, Billai (2019-12-01). Plumes from Paradise. Sydney University Press. p. 114. doi:10.30722/sup.9781743325445. ISBN 978-1-74332-544-5.

- ^ Leonard Andaya (1993), pp. 235–36.

- ^ Muridan Widjojo (2009), pp. 88–93.

- ^ F. S. A. de Clercq (1890), pp. 171–182.

- ^ F. C. Kamma (1947–1949). "De verhouding tussen Tidore en de Papoese eilanden in legende en historie", Indonesië, IV, p. 271.

- ^ Menggali sejarah Papua dari Tidore