Thyroid nodule

| Thyroid nodule | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ultrasound artifacts showing a "comet tail" from a colloid nodule indicate a benign nodule | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery, oncology |

Thyroid nodules are nodules (raised areas of tissue or fluid) which commonly arise within an otherwise normal thyroid gland.[1] They may be hyperplastic or tumorous, but only a small percentage of thyroid tumors are malignant. Small, asymptomatic nodules are common, and often go unnoticed.[2] Nodules that grow larger or produce symptoms may eventually need medical care. A goitre may have one nodule – uninodular, multiple nodules – multinodular, or be diffuse.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Often these abnormal growths of thyroid tissue are located at the edge of the thyroid gland and can be felt as a lump in the throat. When they are large, they can sometimes be seen as a lump in the front of the neck.[citation needed]

Sometimes a thyroid nodule presents as a fluid-filled cavity called a thyroid cyst. Often, solid components are mixed with the fluid. Thyroid cysts most commonly result from degenerating thyroid adenomas, which are benign, but they occasionally contain malignant solid components.[3]

Diagnosis

[edit]After a nodule is found during a physical examination, a referral to an endocrinologist, a thyroidologist or otolaryngologist may occur. Most commonly an ultrasound is performed to confirm the presence of a nodule, and assess the status of the whole gland. Measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone and anti-thyroid antibodies will help decide if there is a functional thyroid disease such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis present, a known cause of a benign nodular goitre.[4] Fine needle biopsy for cytopathology is also used.[5][6][7]

Thyroid nodules are extremely common in young adults and children. Almost 50% of people have had one, but they are usually only detected by a physician during the course of a health examination or fortuitously discovered during the investigation of an unrelated condition.[8]

Workup of incidental nodules

[edit]The American College of Radiology recommends the following workup for thyroid nodules as incidental imaging findings on CT, MRI or PET-CT:[9]

| Features | Workup |

|---|---|

|

Very likely ultrasonography |

| Multiple nodules | Likely ultrasonography |

| Solitary nodule in person younger than 35 years old |

|

| Solitary nodule in person at least 35 years old |

|

Ultrasound

[edit]Ultrasound imaging is useful as the first-line, non-invasive investigation in determining the size, texture, position, and vascularity of a nodule, accessing lymph nodes metastasis in the neck, and for guiding fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or biopsy. Ultrasonographic findings will also guide the indication to biopsy and the long term follow-up.[10] High frequency transducer (7–12 MHz) is used to scan the thyroid nodule, while taking cross-sectional and longitudinal sections during scan. Suspicious findings in a nodule are hypoechoic, ill-defined margins, absence of peripheral halo or irregular margin, fine, punctate microcalcifications, presence of solid nodule, high levels of irregular blood flow within the nodule[11] or "taller-than-wide sign" (anterior-posterior diameter is greater than transverse diameter of a nodule). Features of benign lesion are: hyperechoic, having coarse, dysmorphic or curvilinear calcifications, comet tail artifact (reflection of a highly calcified object), absence of blood flow in the nodule, and presence of cystic (fluid-filled) nodule. However, the presence of solitary or multiple nodules is not a good predictor of malignancy. Malignancy is only diagnosed when ultrasound findings and FNAC report are suggestive of malignancy.[11] The TI-RADS (Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data Systems) are sonographic classification systems which describe the suspicious findings of thyroid nodules.[12] It was first proposed by Horvath et al.,[13] based on the BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) concept. Several systems were subsequently proposed and adopted by international scientific societies. Their main aims are to characterize the risk of malignancy of nodules to better select nodules to submit to fine-needle aspiration cytology.[14] TI-RADS developed by the American College of Radiology (ACR) guides clinicians in deciding which nodules require FNAC and in planning follow-up. Various online tools have been developed to assist in applying these criteria to clinical practice [1].

Another imaging modality, which is ultrasound elastography, is also useful in diagnosing thyroid malignancy especially for follicular thyroid cancer. However, it is limited by the presence of adequate amount of normal tissue around the lesion, calcified shell around a nodule, cystic nodules, coalescent nodules.[15]

Fine needle biopsy

[edit]Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) is a cheap, simple, and safe method in obtaining cytological specimens for diagnosis by using a needle and a syringe.[16] The indications to do FNAC are: nodules more than 1 cm with two ultrasound criteria suggestive of malignancy, nodules of any size with extracapsular extension or lymph nodes enlargement with unknown source, any sizes of nodules with history of head and neck radiation, family history of thyroid carcinoma in two or more first degree relatives, multiple endocrine neoplasia type II, and increased calcitonin levels. However, increased calcitonin levels can also be attributable to smoking, chronic alcohol consumption, usage of proton pump inhibitors, and renal failure.[17] The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology is the system used to report whether the thyroid cytological specimen is benign or malignant. It can be divided into six categories:

| Category | Description | Risk of malignancy[18] | Recommendation[18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Non diagnostic/unsatisfactory | – | Repeating FNAC with ultrasound-guidance in more than 3 months |

| II | Benign (colloid and follicular cells) | 0–3% | Clinical follow-up |

| III | Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS) or follicular lesion of undetermined significance (FLUS) (follicular or lymphoid cells with atypical features) | 5–15% | Repeating FNAC |

| IV | Follicular nodule/suspicious follicular nodule (cell crowding, micro follicles, dispersed isolated cells, scant colloid) | 15–30% | Surgical lobectomy |

| V | Suspicious for malignancy | 60–75% | Surgical lobectomy or near-total thyroidectomy |

| VI | Malignant | 97–99% | Near-total thyroidectomy |

Blood tests

[edit]Blood tests may be done prior to or in lieu of a biopsy. The possibility of a nodule which secretes thyroid hormone (which is less likely to be cancer) or hypothyroidism is investigated by measuring thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Tests for serum thyroid autoantibodies are sometimes done as these may indicate autoimmune thyroid disease (which can mimic nodular disease).[citation needed]

Other imaging

[edit]

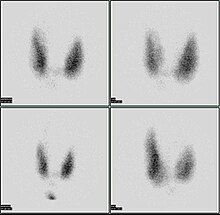

A thyroid scan using a radioactive iodine uptake test can be used in viewing the thyroid.[19] A scan using iodine-123 showing a hot nodule, accompanied by a lower than normal TSH, is strong evidence that the nodule is not cancerous, as most hot nodules are benign.[20]

Computed tomography of the thyroid plays an important role in the evaluation of thyroid cancer.[21] CT scans often incidentally find thyroid abnormalities, and thereby practically becomes the first investigation modality.[21]

Malignancy

[edit]Only a small percentage of lumps in the neck are malignant (around 4 – 6.5%[22]), and most thyroid nodules are benign colloid nodules.

There are many factors to consider when diagnosing a malignant lump. Trouble swallowing or speaking, swollen cervical lymph nodes or a firm, immobile nodule are more indicative of malignancy, whereas a family history of autoimmune disease or goiter, thyroid hormonal dysfunction or a soft, painful nodule are more indicative of benignancy.[citation needed]

The prevalence of cancer is higher in males, patients under 20 years old or over 70 years old, and patients with a history of head and neck irradiation or a family history of thyroid cancer.[23]

Solitary thyroid nodule

[edit]

Risks for cancer

[edit]Solitary thyroid nodules are more common in females yet more worrisome in males. Other associations with neoplastic nodules are family history of thyroid cancer and prior radiation to the head and neck. Solitary thyroid nodules are mostly benign colloid nodules. The second most common type is follicular adenoma.[25]

Radiation exposure to the head and neck may be for historic indications such as tonsillar and adenoid hypertrophy, "enlarged thymus", acne vulgaris, or existent indications such as Hodgkin's lymphoma. Children living near the Chernobyl nuclear power plant during the catastrophe of 1986 experienced a 60-fold increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer. Thyroid cancer arising in the background of radiation is often multifocal with a high incidence of lymph node metastasis and has a poor prognosis.[citation needed]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Worrisome sign and symptoms include voice hoarseness, rapid increase in size, compressive symptoms (such as dyspnoea or dysphagia) and appearance of lymphadenopathy.[citation needed]

Investigations

[edit]- TSH – A thyroid-stimulating hormone level should be obtained first. If it is suppressed, then the nodule is likely a hyperfunctioning (or "hot") nodule. These are rarely malignant.

- FNAC – fine needle aspiration cytology is the investigation of choice given a non-suppressed TSH.[26][27]

- Imaging – Ultrasound and radioiodine scanning.

Thyroid scan

[edit]85% of nodules are cold nodules, and 5–8% of cold and warm nodules are malignant.[28]

5% of nodules are hot. Malignancy is virtually non-existent in hot nodules.[29]

Surgery

[edit]Surgery (thyroidectomy) may be indicated in some instances:

- Reaccumulation of the nodule despite 3–4 repeated FNACs

- Size in excess of 4 cm in some cases

- Compressive symptoms

- Signs of malignancy (vocal cord dysfunction, lymphadenopathy)

- Cytopathology that does not exclude thyroid cancer

Minimally-invasive procedures

[edit]Non-surgical, minimally invasive ultrasound-guided techniques are used for the treatment of large, symptomatic nodules. They include percutaneous ethanol injection, laser thermal ablation, radiofrequency ablation, high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), and percutaneous microwave ablation.[30]

HIFU has recently proved its effectiveness in treating benign thyroid nodules. This method is noninvasive, without general anesthesia and is performed in an ambulatory setting. Ultrasound waves are focused and produce heat enabling them to destroy thyroid nodules.[31] Focused ultrasounds have been used to treat other benign tumors, such as breast fibroadenomas and fibroid disease in the uterus.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]Levothyroxine (T4) is a prohormone that peripheral tissues convert to the primary active thyroid hormone, triiodothyronine (T3). Hypothyroid patients normally take it once per day.

Autonomous thyroid nodule

[edit]An autonomous thyroid nodule or "hot nodule" is one that has thyroid function independent of the homeostatic control of the HPT axis (hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis). According to a 1993 article, such nodules need to be treated only if they become toxic; surgical excision (thyroidectomy), radioiodine therapy, or both may be used.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "New York Thyroid Center: Thyroid Nodules". Archived from the original on 2010-09-17.

- ^ Vanderpump MP (2011). "The epidemiology of thyroid disease". British Medical Bulletin. 99 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldr030. PMID 21893493.

- ^ "Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Bennedbaek FN, Perrild H, Hegedüs L (March 1999). "Diagnosis and treatment of the solitary thyroid nodule. Results of a European survey". Clinical Endocrinology. 50 (3): 357–363. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00663.x. PMID 10435062. S2CID 21514672.

- ^ Ravetto C, Colombo L, Dottorini ME (December 2000). "Usefulness of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma: a retrospective study in 37,895 patients". Cancer. 90 (6): 357–363. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20001225)90:6<357::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 11156519.

- ^ "Thyroid Nodule". www.meddean.luc.edu.

- ^ Grani G, Sponziello M, Pecce V, Ramundo V, Durante C (September 2020). "Contemporary Thyroid Nodule Evaluation and Management". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 105 (9): 2869–2883. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa322. PMC 7365695. PMID 32491169.

- ^ Russ G, Leboulleux S, Leenhardt L, Hegedüs L (September 2014). "Thyroid incidentalomas: epidemiology, risk stratification with ultrasound and workup". European Thyroid Journal. 3 (3): 154–163. doi:10.1159/000365289. PMC 4224250. PMID 25538897.

- ^ Jenny Hoang (2013-11-05). "Reporting of incidental thyroid nodules on CT and MRI". Radiopaedia., citing:

- Hoang JK, Langer JE, Middleton WD, Wu CC, Hammers LW, Cronan JJ, et al. (February 2015). "Managing incidental thyroid nodules detected on imaging: white paper of the ACR Incidental Thyroid Findings Committee". Journal of the American College of Radiology. 12 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.038. PMID 25456025.

- ^ Durante C, Grani G, Lamartina L, Filetti S, Mandel SJ, Cooper DS (March 2018). "The Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules: A Review". JAMA. 319 (9): 914–924. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0898. PMID 29509871. S2CID 5042725.

- ^ a b Wong KT, Ahuja AT (December 2005). "Ultrasound of thyroid cancer". Cancer Imaging. 5 (1): 157–166. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0110. PMC 1665239. PMID 16361145.

- ^ Fernández Sánchez J (July 2014). "Clasificación TI-RADS de los nódulos tiroideos en base a una escala de puntuación modificada con respecto a los criterios ecográficos de malignidad". Revista Argentina de Radiología. 78 (3): 138–148. doi:10.1016/j.rard.2014.07.015.

- ^ Horvath E, Majlis S, Rossi R, Franco C, Niedmann JP, Castro A, Dominguez M (May 2009). "An ultrasonogram reporting system for thyroid nodules stratifying cancer risk for clinical management". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (5): 1748–1751. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1724. PMID 19276237.

- ^ Grani G, Lamartina L, Ascoli V, Bosco D, Biffoni M, Giacomelli L, et al. (January 2019). "Reducing the Number of Unnecessary Thyroid Biopsies While Improving Diagnostic Accuracy: Toward the "Right" TIRADS". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 104 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01674. PMID 30299457.

- ^ Soto GD, Halperin I, Squarcia M, Lomeña F, Domingo MP (10 September 2010). "Update in thyroid imaging. The expanding world of thyroid imaging and its translation to clinical practice". Hormones. 9 (4): 287–298. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1279. PMID 21112859. S2CID 15979225.

- ^ Diana SD, Hossein G. "Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy of the Thyroid Gland". Thyroid Disease Manager. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Feldkamp J, Führer D, Luster M, Musholt TJ, Spitzweg C, Schott M (May 2016). "Fine Needle Aspiration in the Investigation of Thyroid Nodules". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International (in German). 113 (20). Deutsches rzteblatt: 353–359. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0353. PMC 4906830. PMID 27294815.

- ^ a b Renuka IV, Saila Bala G, Aparna C, Kumari R, Sumalatha K (December 2012). "The bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: interpretation and guidelines in surgical treatment". Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. 64 (4): 305–311. doi:10.1007/s12070-011-0289-4. PMC 3477437. PMID 24294568.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Thyroid scan

- ^ Grani, Giorgio; Sponziello, Marialuisa; Filetti, Sebastiano; Durante, Cosimo (2024-08-16). "Thyroid nodules: diagnosis and management". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. doi:10.1038/s41574-024-01025-4. ISSN 1759-5029.

- ^ a b Bin Saeedan M, Aljohani IM, Khushaim AO, Bukhari SQ, Elnaas ST (August 2016). "Thyroid computed tomography imaging: pictorial review of variable pathologies". Insights into Imaging. 7 (4): 601–617. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0506-5. PMC 4956631. PMID 27271508. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ "UpToDate".

- ^ Thyroid Nodule at eMedicine

- ^ Diagram by Mikael Häggström, MD. Source data: Arul P, Masilamani S (2015). "A correlative study of solitary thyroid nodules using the bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology". J Cancer Res Ther. 11 (3): 617–22. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.157302. PMID 26458591.

- ^ Schwartz 7th/e page 1679,1678

- ^ Ali SZ, Cibas ES (2016). "The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology II". Acta Cytologica. 60 (5): 397–398. doi:10.1159/000451071. PMID 27788511. S2CID 32693137.

- ^ Grani G, Calvanese A, Carbotta G, D'Alessandri M, Nesca A, Bianchini M, et al. (January 2013). "Intrinsic factors affecting adequacy of thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration cytology". Clinical Endocrinology. 78 (1): 141–144. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04507.x. PMID 22812685. S2CID 205287747.

- ^ Gates JD, Benavides LC, Shriver CD, Peoples GE, Stojadinovic A (August 2009). "Preoperative thyroid ultrasound in all patients undergoing parathyroidectomy?". The Journal of Surgical Research. 155 (2): 254–260. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.09.012. PMID 19482296.

- ^ Robbins pathology 8ed page 767

- ^ Tumino D, Grani G, Di Stefano M, Di Mauro M, Scutari M, Rago T, et al. (2019). "Nodular Thyroid Disease in the Era of Precision Medicine". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 10: 907. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00907. PMC 6989479. PMID 32038482.

- ^ "Echotherapy for thyroid nodules". Echotherapy.

- ^ Vigneri R, Catalfamo R, Freni V, Giuffrida D, Gullo D, Ippolito A, et al. (December 1993). "[Physiopathology of the autonomous thyroid nodule]". Minerva Endocrinologica. 18 (4): 143–145. PMID 8190053.