Thirty Meter Telescope

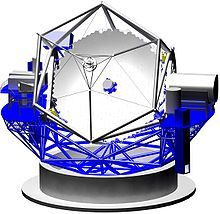

An artist's rendering of proposed telescope | |

| Alternative names | TMT |

|---|---|

| Part of | US Extremely Large Telescope Program |

| Location(s) | Mauna Kea Observatories, Mauna Kea, Hawaii County, Hawaii |

| Coordinates | 19°49'57.7"N, 155°28'53.8"W[1] |

| Organization | TMT International Observatory |

| Altitude | 4,050 m (13,290 ft)[2] |

| Wavelength | Near UV, visible, and Mid-IR (0.31–28 μm) |

| Built | Construction began 2014, halted since 2015 |

| First light | TBD[3] |

| Telescope style | Ritchey–Chrétien telescope |

| Diameter | 30 m (98 ft) |

| Secondary diameter | 3.1 m (10 ft) |

| Tertiary diameter | 2.5 m × 3.5 m (8.2 ft × 11.5 ft) |

| Mass | 2,650 t (2,650,000 kg) |

| Collecting area | 655 m2 (7,050 sq ft)[2] |

| Focal length | f/15 (450 metres [1,480 ft])[2]: 52 |

| Mounting | Altazimuth mount |

| Enclosure | Spherical calotte |

| Website | TMT.org |

| | |

The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) is a planned extremely large telescope (ELT)[5][6][7] proposed to be built on Mauna Kea, on the island of Hawai'i. The TMT would become the largest visible-light telescope on Mauna Kea.[8][9]

Scientists have been considering ELTs since the mid 1980s. In 2000, astronomers considered the possibility of a telescope with a light-gathering mirror larger than 20 meters (66 ft) in diameter, using either small segments that create one large mirror, or a grouping of larger 8-meter (26 ft) mirrors working as one unit. The US National Academy of Sciences recommended a 30-meter (98 ft) telescope be the focus of U.S. interests, seeking to see it built within the decade.

Scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz and Caltech began development of a design that would eventually become the TMT, consisting of a 492-segment primary mirror with nine times the power of the Keck Observatory. Due to its light-gathering power and the optimal observing conditions which exist atop Mauna Kea, the TMT would enable astronomers to conduct research which is infeasible with current instruments. The TMT is designed for near-ultraviolet to mid-infrared (0.31 to 28 μm wavelengths) observations, featuring adaptive optics to assist in correcting image blur. The TMT will be at the highest altitude of all the proposed ELTs. The telescope has government-level support from several nations.

The proposed location on Mauna Kea has been controversial among the Native Hawaiian community.[10][11][12][13] Demonstrations attracted press coverage after October 2014,[14] when construction was temporarily halted due to a blockade of the roadway. When construction of the telescope was set to resume, construction was blocked by further protests each time.[15] In 2015, Governor David Ige announced several changes to the management of Mauna Kea, including a requirement that the TMT's site will be the last new site on Mauna Kea to be developed for a telescope.[16][17] The Board of Land and Natural Resources approved the TMT project,[18][19] but the Supreme Court of Hawaii invalidated the building permits in December 2015, ruling that the board had not followed due process. In October 2018, the Court approved the resumption of construction;[20] however, no further construction has occurred due to continued opposition. In July 2023 a new state appointed oversight board, which includes Native Hawaiian community representatives and cultural practitioners, began a five-year transition to assume management over Mauna Kea and its telescope sites, which may be a path forward.[3] In April 2024, TMT's project manager apologized for the organization having "contributed to division in the community", and stated that TMT's approach to construction in Hawai'i is "very different now from TMT in 2019."[21]

An alternate site for the Thirty Meter Telescope has been proposed for La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain, but is considered less scientifically favorable by astronomers.[22] As of March 2024[update], there were no specific timelines or schedules regarding new start or completion dates.[citation needed]

Background

[edit]In 2000, astronomers began considering the potential of telescopes larger than 20 meters (66 ft) in diameter. The technology to build a mirror larger than 8.4 meters (28 ft) does not exist;[as of?] instead scientists considered two methods: either segmented smaller mirrors as used in the Keck Observatory, or a group of 8-meter (26') mirrors mounted to form a single unit.[23] The US National Academy of Sciences made a suggestion that a 30-meter (98 ft) telescope should be the focus of US astronomy interests and recommended that it be built within the decade.[24]

The University of California, along with Caltech, began development of a 30-meter telescope that same year. The California Extremely Large Telescope (CELT) began development, along with the Giant Segmented Mirror Telescope (GSMT), and the Very Large Optical Telescope (VLOT). These studies would eventually define the Thirty Meter Telescope.[25] The TMT would have nine times the collecting area of the older Keck telescope using slightly smaller mirror segments in a vastly larger group.[23] Another telescope of a large diameter in the works is the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) being built in northern Chile.[7]

The telescope is designed for observations from near-ultraviolet to mid-infrared (0.31 to 28 μm wavelengths). In addition, its adaptive optics system will help correct for image blur caused by the atmosphere of the Earth, helping it to reach the potential of such a large mirror. Among existing and planned extremely large telescopes, the TMT will have the highest elevation and will be the second-largest telescope once the ELT is built. Both use segments of small 1.44 metres (4 ft 9 in) hexagonal mirrors—a design vastly different from the large mirrors of the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) or the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT).[26] Each night, the TMT would collect 90 terabytes of data.[27] The TMT has government-level support from the following countries: Canada, Japan and India.[28][29] The United States is also contributing some funding, but less than the formal partnership.[30][31]

Proposed locations

[edit]

In cooperation with AURA, the TMT project completed a multi-year evaluation of six sites:

- Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain

- Cerro Armazones, Antofagasta Region, Republic of Chile

- Cerro Tolanchar, Antofagasta Region, Republic of Chile

- Cerro Tolar, Antofagasta Region, Republic of Chile

- Mauna Kea, Hawaii, United States (This site was chosen and approval was granted in April 2013)

- San Pedro Mártir, Baja California, Mexico

- Hanle, Ladakh, India[32]

The TMT Observatory Corporation board of directors narrowed the list to two sites, one in each hemisphere, for further consideration: Cerro Armazones in Chile's Atacama Desert and Mauna Kea on Hawaii Island. On July 21, 2009, the TMT board announced Mauna Kea as the preferred site.[33][34] The final TMT site selection decision was based on a combination of scientific, financial, and political criteria. Chile is also where the European Southern Observatory is building the ELT. If both next-generation telescopes were in the same hemisphere, there would be many astronomical objects that neither could observe. The telescope was given approval by the state Board of Land and Natural Resources in April 2013.[19]

There has been opposition to the building of the telescope,[35] based on potential disruption to the fragile alpine environment of Mauna Kea due to construction, traffic, and noise, which is a concern for the habitat of several species,[36] and because Mauna Kea is a sacred site for the Native Hawaiian culture.[37][38] The Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources conditionally approved the Mauna Kea site for the TMT in February 2011. The approval has been challenged; however, the Board officially approved the site following a hearing on February 12, 2013.[39]

Partnerships and funding

[edit]The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation has committed US$200 million for construction. Caltech and the University of California have committed an additional US$50 million each.[40] Japan, which has its own large telescope at Mauna Kea, the 8.3-meter (27 ft) Subaru, is also a partner.[41]

In 2008, the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) joined TMT as a collaborator institution.[42] The following year, the telescope cost was estimated to be $970 million[43] to $1.4 billion.[33] That same year, the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) joined TMT as an observer.[44][45] The observer status is the first step in becoming a full partner in the construction of the TMT and participating in the engineering development and scientific use of the observatory. By 2024, China was not a partner in TMT.

In 2010, a consortium of Indian Astronomy Research Institutes (IIA, IUCAA and ARIES) joined TMT as an observer, subject to approval of funding from the Indian government. Two years later, India and China became partners with representatives on the TMT board. Both countries agreed to share the telescope construction costs, expected to top $1 billion.[46][47] India became a full member of the TMT consortium in 2014. In 2019 the India-based company Larsen & Toubro (L&T) were awarded the contract to build the segment support assembly (SSA), which "are complex optomechanical sub-assemblies on which each hexagonal mirror of the 30-metre primary mirror, the heart of the telescope, is mounted".[48]

The IndiaTMT Optics Fabricating Facility (ITOFF) will be constructed at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics campus in the city of Hosakote, near Bengaluru. India will supply 80 of the 492 mirror segments for the TMT. A.N. Ramaprakash, the associate programme director of India-TMT, stated; "All sensors, actuators and SSAs for the whole telescope are being developed and manufactured in India, which will be put together in building the heart of TMT", also adding; "Since it is for the first time that India is involved in such a technically demanding astronomy project, it is also an opportunity to put to test the abilities of Indian scientists and industries, alike."[48]

The continued financial commitment from the Canadian government had been in doubt due to economic pressures.[28][49] In April 2015, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that Canada would commit $243.5 million over a period of 10 years.[50] The telescope's unique enclosure was designed by Dynamic Structures Ltd. in British Columbia.[51] In a 2019 online petition, a group of Canadian academics called on succeeding Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau together with Industry Minister Navdeep Bains and Science Minister Kirsty Duncan to divest Canadian funding from the project.[52] As of September 2020[update], the Canadian astronomy community has named TMT its top facility priority for the decade ahead.[53]

Design

[edit]

The TMT would be housed in a general-purpose observatory capable of investigating a broad range of astrophysical problems. The total diameter of the dome will be 217 feet (66 m) with the total dome height at 180 feet (55 m) (comparable in height to an eighteen-storey building[54]). The total area of the structure is projected to be 1.44 acres (0.58 ha) within a 5-acre (2.0 ha) complex.[55]

Telescope

[edit]The centerpiece of the TMT Observatory is to be a Ritchey-Chrétien telescope with a 30-metre (98 ft) diameter primary mirror. This mirror is to be segmented and consist of 492 smaller (1.4 meters; 4 ft 7 in), individual hexagonal mirrors. The shape of each segment, as well as its position relative to neighboring segments, will be controlled actively.[56]

A 3.1-metre (10 ft) secondary mirror is to produce an unobstructed field-of-view of 20 arcminutes in diameter with a focal ratio of 15. A 3.5-by-2.5-meter (11.5 ft × 8.2 ft) flat tertiary mirror is to direct the light path to science instruments mounted on large Nasmyth platforms.[57][58] The telescope is to have an alt-azimuth mount.[59] Target acquisition and system configuration capabilities need to be achieved within 5 minutes, or ten minutes if relocating to a newer device. To achieve these time limitations the TMT will use a software architecture linked by a service based communications system.[60] The moving mass of the telescope, optics, and instruments will be about 1,420 tonnes (1,400 long tons; 1,570 short tons).[61] The design of the facility descends from the Keck Observatory.[57]

Adaptive optics

[edit]

Integral to the observatory is a Multi-Conjugate Adaptive Optics (MCAO) system. This MCAO system will measure atmospheric turbulence by observing a combination of natural (real) stars and artificial laser guide stars. Based on these measurements, a pair of deformable mirrors will be adjusted many times per second to correct optical wave-front distortions caused by the intervening turbulence.[62][63]

This system will produce diffraction-limited images over a 30-arc-second diameter field-of-view, which means that the core of the point spread function will have a size of 0.015 arc-second at a wavelength of 2.2 micrometers, almost ten times better than the Hubble Space Telescope.[64]

Scientific instrumentation

[edit]Early-light capabilities

[edit]Three instruments are planned to be available for scientific observations:

- Wide Field Optical Spectrometer (WFOS) provides a seeing limit that goes down to the ultraviolet[65] with optical (0.3–1.0 μm wavelength) imaging and spectroscopy capable of 40-square arc-minute field-of-view.[66] The TMT will use precision cut focal plane masks and enable long-slit observations of individual objects as well as short-slit observations of hundreds of different objects at the same time. The spectrometer will use natural (uncorrected) seeing images.[67]

- Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (IRIS) mounted on the observatory MCAO system, capable of diffraction-limited imaging and integral-field spectroscopy at near-infrared wavelengths (0.8–2.5 μm). Principal investigators are James Larkin of UCLA and Anna Moore of Caltech. Project scientist is Shelley Wright of UC San Diego.[68][69]

- Infrared Multi-object Spectrometer (IRMS) allowing close to diffraction-limited imaging and slit spectroscopy over a 2 arc-minute diameter field-of-view at near-infrared wavelengths (0.8–2.5 μm).

Approval process and protests

[edit]

In 2008, the TMT corporation selected two semi-finalists for further study, Mauna Kea and Cerro Amazones.[70] In July 2009, Mauna Kea was selected.[70] Once TMT selected Mauna Kea, the project began a regulatory and community process for approval.[71] Mauna Kea is ranked as one of the best sites on Earth for telescope viewing and is home to 13 other telescopes built at the summit of the mountain, within the Mauna Kea Observatories grounds.[72] Telescopes generate money for the big island, with millions of dollars in jobs and subsidies gained by the state.[72] The TMT would be one of the most expensive telescopes ever created.[72]

However, the proposed construction of the TMT on Mauna Kea sparked protests and demonstrations across the state of Hawaii.[73] Mauna Kea is the most sacred mountain in Hawaiian culture[73][74][75][76][77][78] as well as conservation land held in trust by the state of Hawaii.[74]

2010-2014: Initial approval, permit and contested case hearing

[edit]In 2010 Governor Linda Lingle of the State of Hawaii signed off on an environmental study after 14 community meetings.[71][79] The BLNR held hearings on December 2 and December 3, 2010, on the application for a permit.[80]

On February 25, 2011, the board granted the permits after multiple public hearings.[71][80] This approval had conditions, in particular, that a hearing about contesting the approval be heard.[80] A contested case hearing was held in August 2011, which led to a judgment by the hearing officer for approval in November 2012. The telescope was given approval by the state Board of Land and Natural Resources in April 2013.[19][80] This process was challenged in court with a lower court ruling in May 2014.[80] The Intermediate Court of Appeals of the State of Hawaii declined to hear an appeal regarding the permit until the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources first issued a decision from the contested case hearing that could then be appealed to the court.[81]

2014-2015: First blockade, construction halts, State Supreme Court invalidates permit

[edit]The dedication and ground-breaking ceremony was held, but interrupted by protesters on October 7, 2014.[82][83][84] The project became the focal point of escalating political conflict,[85] police arrests[86][87][88] and continued litigation over the proper use of conservation lands.[89][90] Native Hawaiian cultural practice and religious rights became central to the opposition,[91] with concerns over the lack of meaningful dialogue during the permitting process.[92] In late March 2015, demonstrators again halted the construction crews.[93] On April 2, 2015, about 300 protesters gathered on Mauna Kea, some of them trying to block the access road to the summit; 23 arrests were made.[94][95] Once the access road to the summit was cleared by the police, about 40 to 50 protesters began following the heavily laden and slow-moving construction trucks to the summit construction site.[94]

On April 7, 2015, the construction was halted for one week at the request of Hawaii state governor David Ige, after the protest on Mauna Kea continued. Project manager Gary Sanders stated that TMT agreed to the one-week stop for continued dialogue; Kealoha Pisciotta, president of Mauna Kea Anaina Hou, one of the organizations that have challenged the TMT in court,[96] viewed the development as positive but said opposition to the project would continue.[97] On April 8, 2015, Governor Ige announced that the project was being temporarily postponed until at least April 20, 2015.[98] Construction was set to begin again on June 24,[15] though hundreds of protesters gathered on that day, blocking access to the construction site for the TMT. Some protesters camped on the access road to the site, while others rolled large rocks onto the road. The actions resulted in 11 arrests.[99]

The TMT company chairman stated: "T.M.T. will follow the process set forth by the state."[100][101] A revised permit was approved on September 28, 2017, by the Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources.[102]

On December 2, 2015, the Hawaii State Supreme Court ruled the 2011 permit from the State of Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) was invalid[103] ruling that due process was not followed when the Board approved the permit before the contested case hearing. The high court stated: "BLNR put the cart before the horse when it approved the permit before the contested case hearing," and "Once the permit was granted, Appellants were denied the most basic element of procedural due process – an opportunity to be heard at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner. Our Constitution demands more".[104][105]

2017-2019: BLNR hearings, Court validates revised permit

[edit]In March 2017, the BLNR hearing officer, retired judge Riki May Amano, finished six months of hearings in Hilo, Hawaii, taking 44 days of testimony from 71 witnesses.[106] On July 26, 2017, Amano filed her recommendation that the Land Board grant the construction permit.[107] On September 28, 2017, the BLNR, acting on Amano's report, approved, by a vote of 5-2, a Conservation District Use Permit (CDUP) for the TMT. Numerous conditions, including the removal of three existing telescopes and an assertion that the TMT is to be the last telescope on the mountain, were attached to the permit.[108][109]

On October 30, 2018, the Supreme Court of Hawaii ruled 4-1, that the revised permit was acceptable, allowing construction to proceed.[110][20] On July 10, 2019, Hawaii Gov. David Ige and the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory jointly announced that construction would begin the week of July 15, 2019.[111]

2019 blockade and aftermath

[edit]On July 15, 2019, renewed protests blocked the access road, again preventing construction from commencing. On July 17, 38 protestors were arrested, all of whom were kupuna (elders) as the blockage of the access road continued.[112][113] The blockade lasted 4 weeks and shut down all 12 observatories on Mauna Kea, the longest shut down in the 50-year history of the observatories. The full shut down ended when state officials brokered a deal that included building a new road around the campsite of the demonstrations and providing a complete list of vehicles accessing the road to show they are not associated with the TMT.[114] The protests were labeled a fight for indigenous rights[115] and a field-defining moment for astronomy. While there is both native and non-native Hawaiian support for the TMT, a "substantial percentage of the native Hawaiian population" oppose the construction and see the proposal itself as a continued disregard to their basic rights.[116]

The 50 years of protests against the use of Mauna Kea has drawn into question the ethics of conducting research with telescopes on the mountain.[117] The controversy is about more than the construction and is about generations of conflict between Native Hawaiians, the U.S. Government and private interests. The American Astronomical Society stated through their Press Officer, Rick Fienberg; "The Hawaiian people have numerous legitimate grievances concerning the way they’ve been treated over the centuries. These grievances have simmered for many years, and when astronomers announced their intention to build a new giant telescope on Maunakea, things boiled over".[118] On July 18, 2019, an online petition titled "Impeach Governor David Ige" was posted to Change.org. The petition gathered over 25,000 signatures.[119] The governor and others in his administration received death threats over the construction of the telescope.[120]

On December 19, 2019, Hawaii Governor David Ige announced that the state would reduce its law enforcement personnel on Mauna Kea.[121] At the same time, the TMT project stated it was not prepared to start construction anytime soon.[122]

2020s

[edit]

Early in 2020, TMT and the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) jointly presented their science and technical readiness to the U.S. National Academies Astro2020 panel.[123] Chile is the site for GMT in the south and Mauna Kea is being considered as the primary site for TMT in the north. The panel has produced a series of recommendations for implementing a strategy and vision for the coming decade of U.S. Astronomy & Astrophysics frontier research and prioritize projects for future funding.[124][125]

In July 2020, TMT confirmed it would not resume construction on TMT until 2021, at the earliest.[126] The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in TMT's partnership working from home around the world and presented a public health threat as well as travel and logistical challenges.

On August 13, 2020, the Speaker of the Hawaii House of Representatives, Scott Saiki announced that the National Science Foundation (NSF) has initiated an informal outreach process to engage stakeholders interested in the Thirty Meter Telescope project.[127] After listening to and considering the stakeholders’ viewpoints, the NSF acknowledged a delay in the environmental review process for TMT while seeking to provide a more inclusive, meaningful, and culturally appropriate process.[128]

In November 2021, Fengchuan Liu was appointed the Project Manager of TMT and moved his office to Hilo.[129]

As of March 2024[update], no further construction was announced or initiated. Continued progress on instrument design, mirror casting & polishing, and other critical operational technicalities were worked through or were being worked on.[130][131] In July 2023 a new state appointed board, the Maunakea Stewardship Oversight Authority, began a five-year transition to assume management over the Mauna Kea site and all telescopes on the mountain. While there are no specific timelines or schedules regarding new start or completion dates, activist Noe Noe Wong-Wilson is quoted by Astronomy magazine as saying, "It's still early in the life of the new authority, but there's actually a pathway forward." The authority includes representatives from Native Hawaiian communities and cultural practitioners as well as astronomers and others. The body will have full control of the site from July 2028.[3]

Opposition in the Canary Islands

[edit]In response to the ongoing protests that occurred in July 2019, the TMT project officials requested a building permit for a second site choice, the Spanish island of La Palma in the Canary Islands. Rafael Rebolo, the director of the Canary Islands Astrophysics Institute, confirmed that he had received a letter requesting a building permit for the site as a backup in case the Hawaii site cannot be constructed.[132] Some astronomers argue however that La Palma is not an adequate site to build the telescope due to the island’s comparatively low elevation, which would enable water vapor to frequently interfere with observations due to water vapor’s tendency to absorb light at midinfrared wavelengths.[22] Such atmospheric interference could impact observing times for research into exoplanets, galactic formation, and cosmology.[22] Other astronomers argue that construction of the telescope in La Palma would disrupt projected international collaboration between the United States and other involved countries such as Japan, Canada, and France.[22]

Environmentalists such as Ben Magec and the environmental advocacy organization Ecologistas en Acción in the Canary Islands are gearing up to fight against its construction there as well. According to EEA spokesperson Pablo Bautista, the projected TMT construction area in the Canary Islands exists inside a protected conservation refuge which hosts at least three archeological sites of the indigenous Guanche people, who lived on the islands for thousands of years before Spanish colonization.[22] On July 29, 2021, Judge Roi López Encinas of the High Court of Justice of the Canary Islands, revoked the 2017 concession of public lands by local authorities for the TMT construction.[133] Encinas ruled that the land concessions were invalid as they were not covered by an international treaty on scientific research and that the TMT International Observatory consortium did not express concrete intent to build on the La Palma site as opposed to the site in Mauna Kea.[133]

On July 19, 2022, The National Science Foundation announced it will carry out a new environmental survey of the possible impacts of the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope at proposed building sites at both Mauna Kea and at the Canary Islands.[134] Continued funding for the telescope will not be considered prior to the results of the environmental survey, updates on the project's technical readiness, and comments from the public.[134]

By 2023, TIO has addressed all protests and they are clear to build there now.[135]

See also

[edit]- Extremely Large Telescope

- Very Large Telescope

- Giant Magellan Telescope

- List of largest optical reflecting telescopes

References

[edit]- ^ Sanders, Gary H. (January 11, 2005), [79.03] The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) Project (PDF), p. 17, archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011

- ^ a b c d Thirty Meter Telescope Construction Proposal (PDF), TMT Observatory Corporation, September 12, 2007, p. 29, archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2016, retrieved July 24, 2009

- ^ a b c Zastrow, Mark (March 29, 2023). "Path forward for Thirty Meter Telescope, Mauna Kea begins to emerge". Astronomy. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Thirty Meter Telescope Selects Mauna Kea". TMT Observatory Corporation. July 21, 2009. Archived from the original on September 1, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 8, 2024). "Good News and Bad News for Astronomers' Biggest Dream - The National Science Foundation takes a step (just one) toward an "extremely large telescope."". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Perryman, Michael (August 31, 2018). The Exoplanet Handbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-108-32966-8.

- ^ a b Govert Schilling; Lars Lindberg Christensen (December 7, 2011). Eyes on the Skies: 400 Years of Telescopic Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-527-65705-6.

- ^ "What is TMT?". TMT International Observatory. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Caleb (June 20, 2019). "Controversial telescope to be built on sacred Hawaiian peak". AP News. Associated Press.

- ^ "'We put everything into it.' Modest telescope could have big impact on Turkish science". Science. March 4, 2020.

- ^ "Controversy over giant telescope roils astronomy conference in Hawaii". Space.com. January 16, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Why are Jason Momoa and other Native Hawaiians protesting a telescope on Mauna Kea? What's at stake?". USA today. August 21, 2019.

- ^ "'This is our last stand.' Protesters on Mauna Kea dig in their heels". CNN. July 22, 2019.

- ^ Herman, Doug (April 23, 2015). "The Heart of the Hawaiian Peoples' Arguments Against the Telescope on Mauna Kea". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "Astronomers to restart construction of controversial telescope in Hawaii". news.sciencemag.org. June 21, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ "Governor David Ige announces major changes in the stewardship of Mauna Kea". Governor of Hawaii. May 26, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "UPDATE: Notice to Proceed Granted for Thirty Meter Telescope | Big Island Now". Big Island now. June 20, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

We also accept the increased responsibilities for the stewardship of Maunakea, including the requirement that as this very last site is developed for astronomy on the mauna, five current telescopes will be decommissioned and their sites restored."

- ^ McKinnon, Mika. "Construction Permits Revoked on the Thirty-Meter Telescope in Hawaii". Earth & Space. Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Massive telescope to be built in Hawaii". 3 News NZ. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Hawaii top court approves controversial Thirty Meter Telescope". BBC News. October 31, 2018.

- ^ Brestovansky, Michael. "TMT project manager admits past mistakes, notes project is dependent on NSF funding, support from Hawaiians". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Stalled in Hawaii, giant telescope faces roadblocks at its backup site in the Canary Islands". www.science.org. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Ratcliffe, Martin (February 1, 2008). State of the Universe 2008: New Images, Discoveries, and Events. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-387-73998-4.

- ^ A.P. Lobanov; J.A. Zensus; C. Cesarsky; Ph. Diamond (February 15, 2007). Exploring the Cosmic Frontier: Astrophysical Instruments for the 21st Century. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-540-39756-4.

- ^ Whitelock, Patricia Ann (2006). The Scientific Requirements for Extremely Large Telescopes: Proceedings of the 232nd Symposium of the International Astronomical Union Held in Cape Town, South Africa, November 14–18, 2005. Cambridge University Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-521-85608-9.

- ^ Anderson, Margo (March 13, 2014). "The Billion-Dollar Telescope Race". Nautilus. New York: NautilusThink.

- ^ Brady, Henry Eugene (May 11, 2019). "The Challenge of Big Data and Data Science". Annual Review of Political Science. 22 (1): 297–323. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-090216-023229. ISSN 1094-2939.

- ^ a b Moon, Mariella (March 18, 2015). "Canada's economic issues might affect Thirty Meter Telescope's future". Engadget. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Megascope member". Seven Days. Nature (paper). 516 (7530): 148–149. December 11, 2014. Bibcode:2014Natur.516..148.. doi:10.1038/516148a.

India announced on 2 December that it will become a full partner in the Thirty Meter Telescope....

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit (March 19, 2013). "Thirty Meter Telescope Gets Small Grant to Make Big Plans". Science, journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit (January 3, 2012). "Giant Telescopes Face NSF Funding Delay". Science, journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Ladakh to get world's largest telescope". timesofindia.com. March 26, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ a b Xin, Ling (October 9, 2014). "TMT opening ceremony interrupted by protests". Science. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ McAvoy, Audrey (July 22, 2009). "World's largest telescope to be built in Hawaii". Phys.org. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Hearing on Hawaii Thirty Meter Telescope to continue next week – Pacific Business News". Bizjournals.com. August 19, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Summit Ecosystems — KAHEA". Kahea.org. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Sacred Landscape — KAHEA". Kahea.org. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Hawaii Tribune Herald". Hawaii Tribune Herald. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "TMT Takes Step Towards Construction after Approval by the Board of Land and Natural Resources | Thirty Meter Telescope". Tmt.org. April 13, 2013. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Perry, Jill (December 5, 2007). "Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Commits $200 Million Support for Thirty-Meter Telescope". Caltech. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "India Joins Thirty Meter Telescope Project". Thirty Meter Telescope. June 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Thirty Meter Telescope". Tmt.org. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Mann, Adam (November 16, 2009). "Titanic Thirty Meter Telescope Will See Deep Space More Clearly". Wired. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "Thirty Meter Telescope". Tmt.org. November 17, 2009. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "China, India to jump forward with Hawaii telescope". Associated Press. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ "Construction of 30-meter optical telescope to begin next year". The Economic Times. January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "China, India to work for largest telescope". The Hindu. January 13, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ a b "India to Start Manufacturing Key Components for Thirty Meter Telescope Project". The Wire. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "World's largest telescope stalled by Canadian funding woes". CBC News. October 10, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Canada finally commits its share of funds for Thirty Meter Telescope". CBC News.

- ^ Semeniuk, Ivan (April 6, 2015). "With $243-million contribution, Canada signs on to mega-telescope in search of first stars and other Earths". Globe and Mail.

- ^ Semeniuk, Ivan (July 22, 2019). "Thirty Meter Telescope dispute puts focus on Canada's role". www.theglobeandmail.com. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ Bellrichard, Chantelle (September 27, 2020). "Canadian astronomers contend with issue of Indigenous consent over Hawaiian telescope project". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Worth, Katie (February 20, 2015). "World's Largest Telescope Faces Opposition from Native Hawaiian Protesters". Scientific American. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Thirty Meter Telescope Detailed Science Case : 2007" (PDF). Tmt.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ Stepp, Larry M.; Thompson, Peter M.; MacMynowski, Douglas G.; Regehr, Martin W.; Colavita, M. Mark; Sirota, Mark J.; Gilmozzi, Roberto; Hall, Helen J. (2010). Stepp, Larry M; Gilmozzi, Roberto; Hall, Helen J (eds.). "Servo design and analysis for the Thirty Meter Telescope primary mirror actuators" (PDF). Ground-based and Airborne Telescopes III. 7733: 77332F–77332F–14. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7733E..2FT. doi:10.1117/12.857371. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 34865540.

- ^ a b "TMT Optics". Thirty Meter Telescope. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Ellerbroek, Brent L.; Boyer, C.; Bradley, C.; Britton, M. C.; Browne, S.; et al. (2006). "A conceptual design for the Thirty Meter Telescope adaptive optics systems" (PDF). Advances in Adaptive Optics II. SPIE Conference Series. Vol. 6272. pp. 62720D–62720D–14. Bibcode:2006SPIE.6272E..0DE. doi:10.1117/12.669422. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 120741170.

- ^ Gawronski, W. (2005). "Control and pointing challenges of antennas and telescopes". Proceedings of the 2005, American Control Conference, 2005. pp. 3758–3769. doi:10.1109/ACC.2005.1470558. ISBN 0-7803-9098-9. S2CID 13452336.

- ^ Bridger, Alan; Silva, David R.; Angeli, George; Boyer, Corinne; Sirota, Mark; Trinh, Thang; Radziwill, Nicole M. (2008). "Thirty Meter Telescope: Observatory software requirements, architecture, and preliminary implementation strategies". Advanced Software and Control for Astronomy II. Vol. 7019. pp. 70190X–70190X–12. Bibcode:2008SPIE.7019E..0XS. doi:10.1117/12.789974. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 17768964.

- ^ Gough, Evan (March 7, 2017). "Rise of the Super Telescopes: The Thirty Meter Telescope". Universe Today. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Rochester, Simon M.; Otarola, Angel; Boyer, Corinne; Budker, Dmitry; Ellerbroek, Brent; Holzlöhner, Ronald; Wang, Lianqi (2012). "Modeling of pulsed-laser guide stars for the Thirty Meter Telescope project". Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 29 (8): 2176. arXiv:1203.5900. Bibcode:2012JOSAB..29.2176R. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.29.002176. ISSN 0740-3224. S2CID 13072542.

- ^ Hippler, Stefan (2019). "Adaptive Optics for Extremely Large Telescopes". Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation. 8 (2): 1950001–322. arXiv:1808.02693. Bibcode:2019JAI.....850001H. doi:10.1142/S2251171719500016. S2CID 119505402.

- ^ Ellerbroek, Brent; Adkins, Sean; Andersen, David; Atwood, Jennifer; Browne, Steve; et al. (2010). "First light adaptive optics systems and components for the Thirty Meter Telescope" (PDF). In Ellerbroek, Brent L; Hart, Michael; Hubin, Norbert; Wizinowich, Peter L (eds.). Adaptive Optics Systems II. Vol. 7736. pp. 773604–773604–14. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7736E..04E. doi:10.1117/12.856503. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 55477536.

- ^ Moorwood, Alan F. M. (November 21, 2008). Science with the VLT in the ELT Era. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-4020-9190-2.

- ^ Kevin H. Baines; F. Michael Flasar; Norbert Krupp; Tom Stallard (December 6, 2018). Saturn in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. ISBN 978-1-107-10677-2.

- ^ Kamphues, Fred (2016). "www.maunakeaandtmt.org" (PDF). Mikeroniek. p. 14. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "IRIS Home Page". Irlab.astro.ucla.edu. October 5, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Ellerbroek, Brent; Joyce, Richard; Boyer, Corinne; Daggert, Larry; Hileman, Edward; Hunten, Mark; Liang, Ming; Bonaccini Calia, Domenico (2006). "The laser guide star facility for the Thirty Meter Telescope" (PDF). Advances in Adaptive Optics II. SPIE Conference Series. Vol. 6272. pp. 62721H–62721H–13. Bibcode:2006SPIE.6272E..1HJ. doi:10.1117/12.670070. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 123191350.

- ^ a b "Thirty Meter Telescope". Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c "About TMT". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c Dickerson, Kelly (November 18, 2015). "This giant telescope may taint sacred land. Here's why we should build it anyway". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Zara, Christopher (April 4, 2015). "TMT Mauna Kea Protests Heat Up: Site Of Thirty Meter Telescope Called 'Sacred' By Native Hawaiian Leaders". IBT Media Inc. International Business Times. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Nelson, Jonathan (June 29, 2015). "Who Owns the Rights to Mauna Kea?". E21. economics21.org. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Gray, Martin (2007). Sacred Earth: Places of Peace and Power. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-4027-4737-3.

Mauna Kea, the most sacred mountain to native Hawaiians was the site of ongoing religious ritual practice.

- ^ Gutierrez, Ben (April 10, 2015). "Protest against Thirty Meter Telescope spreading worldwide". Honolulu: Hawaii News Now.

Mauna Kea is sacred, and our children are taught to respect our `aina," said teacher Leo Akana. "They understand that science is an important thing, but I think the state needs to realize that Hawaiians were the very first astronomers here.

- ^ "Mauna Kea | Indigenous Religious Traditions". Indigenous Religious Traditions. November 18, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

Mauna Kea is sacred to the Native Hawaiians and is the zenith of their ancestral ties to creation.

- ^ "Mauna Kea - The Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA)". Retrieved February 13, 2020.

Mauna Kea is a deeply sacred place that is revered in Hawaiian traditions. It's regarded as a shrine for worship, as a home to the gods, and as the piko of Hawaiʻi Island.

- ^ "Final Environmental Imapact Statement, volume II, section 8.0" (PDF). Hawaii.gov. May 8, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Stewart, Colin M.; Burnett, John (December 3, 2015). "Hawaii Supreme Court voids Thirty Meter Telescope permit". West Hawaii Today. Black Press. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Winpenny, Jamie (June 26, 2013). "The Uncertain Future of Mauna Kea". Big Island Weekly. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ "Protesters disrupt Mauna Kea telescope groundbreaking". KITV4 News. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Hodges, Lauren (October 8, 2014). "Protesters disrupt telescope groundbreaking in Hawaii". NPR: National Public Radio. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Beatty, J. Kelly. "Work begins on Thirty Metre Telescope". Australian Sky & Telescope (83). Odysseus Publishing Pty Ltd: 11. ISSN 1832-0457.

- ^ Beittel, Lynn (April 1, 2015). "VIDEO: Why block TMT on Mauna Kea?". Big Island Video News. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Protesters arrested blocking road to giant telescope site". KITV4 News. April 2, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Epping, Jamilia (April 3, 2015). "DLNR makes additional protest arrests". Big Island Now.com. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Gutierrez, Ben (April 4, 2015). "A day after arrests Mauna Kea telescope protest grows". Hawaii News Now. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Callis, Tom (August 29, 2014). "TMT project headed back to court: 4 appeal denial of contested case hearing request for sublease". West Hawaii Today. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Hussey, Ikaika (February 20, 2014). "Board of regents vote in favor of mauna kea sublease plan despite lawsuit, demonstrations". The Hawaii Independent. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Saks, Dominique (November 19, 2011). "Indigenous religious traditions: Mauna Kea". Indigenous Religious Traditions. Colorado College. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Blair, Chad (April 4, 2015). "OHA trustee calls for moratorium on Mauna Kea telescope". Honolulu Civil Beat and KITV4 News. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Chelsea (March 26, 2015). "Thirty Meter Telescope protesters continue to block construction on Mauna Kea". KHNL. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Jones, Caleb (April 3, 2015). "Clash in Hawaii Between Science and Sacred Land". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Staff (April 2, 2015). "Police, TMT Issue Statements on Mass Arrests on Mauna Kea". Big Island Video News. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Hawaii Court Rescinds Permit to Build Thirty Meter Telescope

- ^ Jones, Caleb (April 7, 2015). "Amid controversy, construction of telescope in Hawaii halted". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Yoro, Sarah (April 11, 2015). "Thirty Meter Telescope construction delayed". KHON2. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Dickerson, Kelly (June 25, 2015). "Protesters just blocked the construction of a revolutionary scientific instrument – again". Business Insider. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (December 3, 2015). "Contested case hearing". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ "APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE THIRD CIRCUIT(CAAP-14-0000873; CIV. NO. 13-1-0349)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ 09/28/17 – Board of Land and Natural Resources Approves TMT Permit

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (2015). "Hawaiian court revokes permit for planned mega-telescope". Nature. 528 (7581). Nature.com: 176. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..176W. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18944. PMID 26659163.

- ^ Knapp, Alex (December 3, 2015). "Hawaii Supreme Court Revokes Construction Permit for Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea". Forbes.com. Forbes.com. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Hou v. Board of the Land and Natural Resources, 363 P.3d 224, 136 Haw. 376 (2015).

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (July 28, 2017). "Giant Telescope Atop Hawaii's Mauna Kea Should Be Approved, Judge Says". The New York Times. p. A13. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ Proposed Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Decision and Order, In re Contested Case Hearing Re Conservation District Use Application (CDUA) HA-3568 For the Thirty Meter Telescope at the Mauna Kea Science Reserve, Ka`ohe Mauka, Hamakua, Hawai‘i TMK (3) 4-4-015:009.

- ^ "Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources Approves Conservation District Use Permit to Build TMT on Maunakea". September 29, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "Hawai'i BLNR Approves TMT Permit". Big Island Now. September 28, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "State Supreme Court rules in favor of Thirty Meter Telescope's construction". Hawaii News Now. October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ Hofschneider, Anita (July 10, 2019). "Thirty Meter Telescope Construction Will Start Next Week". Civil Beat. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Kelleher, Jennifer Sinco; Jones, Caleb (July 18, 2019). "Hawaiian Elders Arrested as Standoff Continues Over a Telescope Slated for a Sacred Mountain". Time. AP Press. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019.

- ^ "DLNR releases names of those arrested on Maunakea". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. July 26, 2019.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (August 13, 2019). "Telescopes in Hawaii reopen after deal with protesters | Science | AAAS". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Funes, Yessenia (August 9, 2019). "Mauna Kea's Thirty Meter Telescope Is the Latest Front in the New Fight for Indigenous Sovereignty". Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan (August 9, 2019). "Astronomy Faces A Field-Defining Choice In Choosing The Next Steps For The TMT". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

A substantial percentage of the native Hawaiian population not only opposes the construction of any new telescopes or structures atop Mauna Kea, but view the very proposal of the TMT atop Mauna Kea as continuing a long history of disregard for their basic rights.

- ^ Peryer, Marisa (July 27, 2019). "For years, Yale's Astro Dept. has conducted research on Native Hawaiian cultural site". Yale Daily News. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Hess, Peter (August 13, 2019). "Hawaii's Space Telescope Controversy Is Reopening Old Wounds | Inverse". Inverse. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "Petition on change.org calls for impeachment of Governor David Ige". KITV. July 19, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Gov. David Ige decries death threats over Thirty Meter Telescope". STAR-ADVERTISER. September 13, 2019.

- ^ "OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR — Statement by Governor David Ige on Mauna Kea/TMT". governor.hawaii.gov. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "In major deal, TMT protesters agree to temporarily clear Mauna Kea Access Road". Hawaii News Now. December 26, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 18, 2020). "American Astronomy's Future Goes on Trial in Washington". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "2020 Decadal Survey". NASA. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020 (Astro2020)". National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Construction of Thirty Meter Telescope probably won't resume until 2021". Hawaii News Now. July 15, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Speaker Saiki Announces National Science Foundation's Outreach for Thirty Meter Telescope". hawaiihousedemocrats. August 19, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Thirty Meter Telescope". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "TMT Appoints Dr. Fengchuan Liu as Project Manager". TIO. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ "TMT International Observatory".

- ^ "TMT International Observatory".

- ^ Joseph Wilson; Caleb Jones (August 5, 2019). "Still blocked from Hawaii peak, telescope seeks Spain permit". The Associated press. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ a b "Spain judge nixes backup site for disputed Hawaii telescope". AP NEWS. August 25, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "US environmental study launched for Thirty Meter Telescope". AP NEWS. July 19, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ "BOE-A-2023-26716 Resolución de 19 de diciembre de 2023, del Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, por la que se publica la segunda Adenda de modificación del Convenio con el Cabildo Insular de La Palma y el Ayuntamiento de Puntagorda, para la ampliación de la superficie actual del Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos, con motivo de la posible instalación del denominado Thirty Meter Telescope para la investigación científica". www.boe.es. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Mauna Kea page at the Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources

- INSIGHTS ON PBS HAWAII Should the Thirty Meter Telescope Be Built? (air-date video; April 30, 2015)